Natura morta (literally, “dead nature”) is really just the dramatic Italian phrase for “still life”; those oil paintings you’ve seen depicting everyday natural objects like flowers, fruit, and other foods. Caravaggio even gave it a crack, a few years after Bacchus overindulged at a banquet and Judith severed a man’s head. But compared to its English counterpart, the Italian phrase evokes poetic ideas of beginnings and endings, of time and cycles, and the inevitable decay of all living things. Observing Tessa Chung’s still-life photography is rather like seeing Caravaggio’s Still Life with Fruit (1601) or Fede Galizia’s A Crystal Fruit Stand with Peaches, Quinces, and Jasmine Flowers (1607) in a parallel contemporary dimension.

In 2020, during the pandemic, the Florence-based photographer of Chinese heritage started shooting decaying fruit lying around her apartment. Her curiosity to explore this subject matter was no doubt influenced (if even subconsciously) by the subject of a master’s thesis she was completing in Florence at the time; a research project on food and its symbolic role in visual culture, from classical paintings to modern and contemporary photography. While she describes its influence on her work as a case of “theory before practice”, Chung’s lens has evolved to reflect an intricate cross-cultural dialogue between food traditions from her own Chinese culture and those of her adopted home, Italy.

Despite what the postcards show you, it’s not always sunny in Florence. Chung prefers it that way, reflecting that the city has shaped her photographic approach more than she ever expected. The city’s galleries, streetscapes, and artisanal history, sure, but in addition, the way the Florentine sky acts as a “giant softbox” on cloudy days, providing the perfect conditions in which to shoot her still-life food images. “I might set everything up, shoot for half an hour, then leave the entire set untouched until the next day, or even the next month, just waiting for the right light to fall into place. When it does, I simply pick up my camera and take the shot. It’s almost as if the image is already there, just waiting for the right moment to be seen,” Chung says.

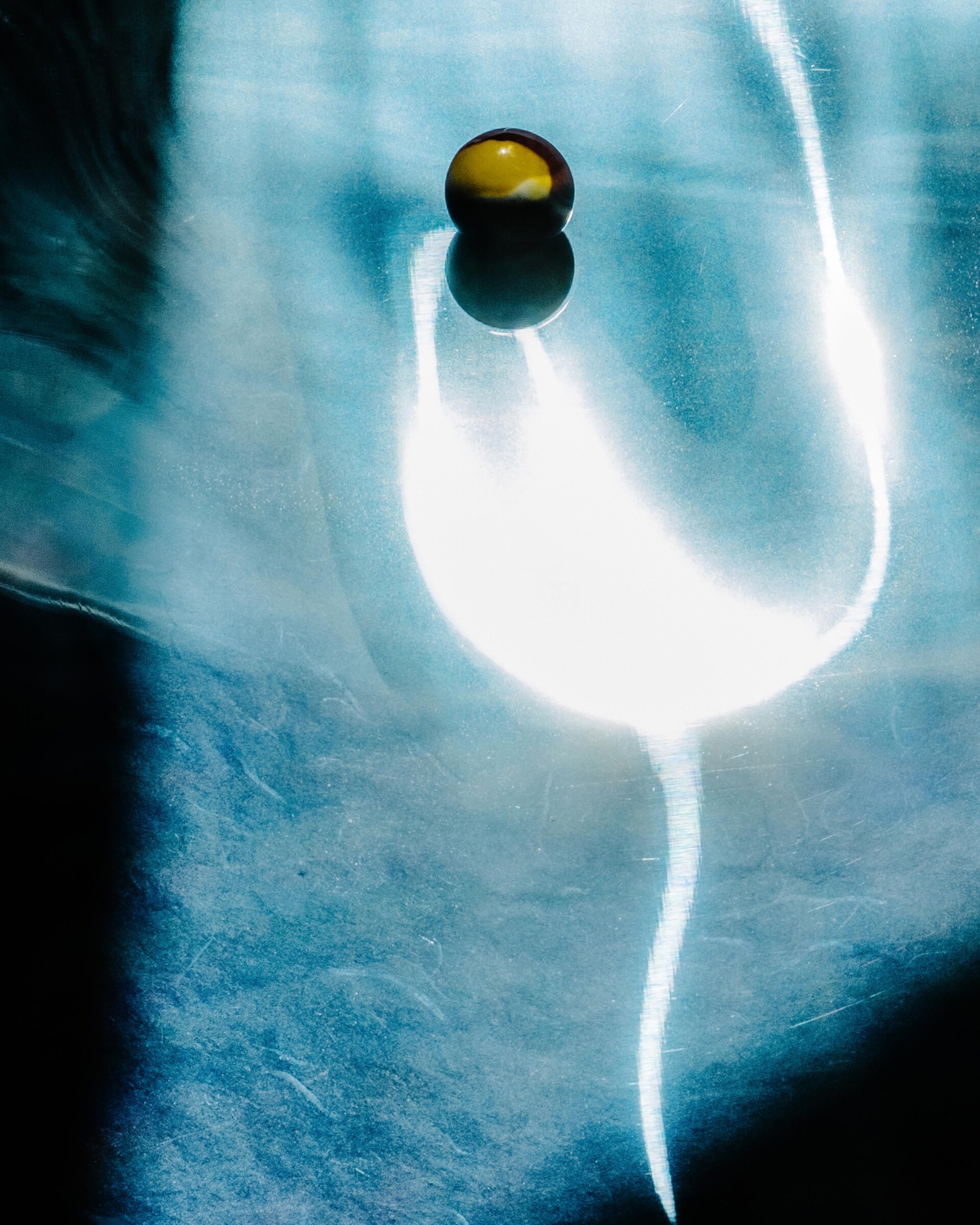

Eggs, artichokes, rose petals…that’s not necessarily a typical Florentine grocery list. But it’s the natural matter Chung left arranged “en scene” on a table for four months until the right conditions transpired to photograph them. It seems rather like how Galizia or Caravaggio would have approached their still-life canvases, anticipating the right moment when the right light cast the right chiaroscuro upon their subject matter, thereby “creating” the image that the artists were compelled to capture in brushstrokes. In Chung’s still-life photographs, it’s as though her subject matter has always existed in those states, those very poetic arrangements. While the photographer also shoots portraits, environmental, and documentary-style reportage, and a range of commercial projects for clients, her inspiration for her still-life images often comes from a place of objective observation and experimentation. Other times, it’s ignited by a deeper emotional response, as was the case with her Riso Cantonese series, which, she explains, came from a sense of deep nostalgia for her homeland.

“The title is for fun; Riso Cantonese is such an Italian thing. I grew up in Canton, but I only heard of such a thing when I first stepped into a Chinese restaurant here in Italy,” she shares.

Italians, we know, are rather proud of their national cuisine. Among older generations, enduring traditions of a hyper-localized food culture have even caused a sense of resistance against embracing multicultural cuisine. This is gradually shifting with younger generations, and Chung is observing the evolution of culinary diversity in Italy as a source of creative inspiration.

Visual culture meets food culture; that’s not just how one might describe this aspect of Chung’s photographic “lens”, but also how she comprehends aspects of her experience living halfway around the world. Sure, she is well-attuned to the differences between Chinese food culture and traditions and those from Italy, but she is equally perceptive to the similarities between them. The common thread is that golden word “tradition”; the idea of honoring those centuries-old customs and rituals that underlie both preparing and sharing meals. She observes it in the most minute details. Even the sounds of clinking cups, plates, and bowls in the kitchen, for example, evoke a sense of familiarity with home for her. A few other quick examples come to mind for Chung:

“…the countless variations of dough: noodles and pasta, dumplings and ravioli, wontons and tortellini. Then there’s salami and là cháng (臘腸), lampredotto and Cantonese niú zá (牛雜), and finally, the act of sharing—whether it’s the communal feasts of long tables or the shared experience of hot pot.”

Italian breakfasts were, still are, a little odd for Chung, who grew up with a routine breakfast of a dim sum spread across a large round table at 7:30 AM, which she shared with “a bunch of nonni, chatting away over tea.” She’s not the only one to consider the classic cornetto e caffè a little too sweet, too simple, for the day’s first meal. But these differences in food culture between her home and her adopted home, which often reflect daily lifestyle habits and cultural nuances, continue to ignite her sense of curiosity and inspire her photographic explorations. There’s no doubt that her decision to move to Florence has been the catalyst for a new chapter in her life and work, an experience she calls “a privilege.” Not everyone can study Caravaggio’s paintings in a university textbook one day and find themselves standing face to face with them in the Uffizi the next.

“The city before 7 AM is another huge source of inspiration for me! The first sunlight, the tranquility. When I run along the Arno in the morning, it feels like I own the city. There are only pigeons on the Ponte Vecchio or Piazzale Michelangelo around that time of day,” she says.

This July, it will be five years since Chung first moved to Florence. She has observed a lot of the country in that time, forming her own opinions about what makes an image feel authentically “Italian”. As her work continues to evolve with each photographic series and commission, she continues to push against the mass of clichéd, stereotypical, and idealized representations of Italian culture and lifestyle, which she believes have created an “iconoclast” of their own, thanks to what the world sees on social media.

Despite what our screens show us, the essence of “Italy”, while of course subjective for every person, is not necessarily found in visions of the perfect, the polished, or anything that consciously has to assert itself as an expression of “Italianicity”. The beauty is that it simply is. It’s more likely closer to the visual poetry of a month-old bowl of citrus fruits on a table, skins ageing gracefully in the sunlight, than it is to an Instagram reel about where to find the best Limoncello spritz in Amalfi. In Chung’s case, it’s sometimes less about what you’re looking at in her images and more about the sense of unfiltered honesty, imperfection, and authenticity they evoke. That’s Italy.

“I’ve become increasingly interested in what truly defines Italy today—looking beyond how the market has branded it. I hope my body of work offers a fresh perspective on the familiar, whether it’s within the context of Italy, during my annual visits to my homeland in China, or on my travels elsewhere.”