An Italian train station is notoriously a place of chaos. Backpackers slump against their human-sized packs in waiting rooms, confused tourists drag way-too-large suitcases through entry points, late–or changed–binario announcements cause stampedes towards the arriving trains, and automated ticket points loudly warn you to “beware of pickpockets.” It’s rare to stop and admire a station the way we do so many other places–churches, monuments, piazzas–but there are many in Italy that certainly warrant a second (or third) glance. After all, we Italians have never been known to do anything simply, and our country was one of the first nations in the world to build a railway line.

These initial railways corresponded to the needs of the then-current seats of power, like the creation of the Naples-Salerno route in 1839 under the Bourbon Kingdom, the Padua-Mestre line in 1842 to connect the capitals of the Lombardy-Veneto Kingdom, and the 1853 Turin-Genoa route under the Kingdom of Sardinia. On the eve of the unification of Italy, the Piedmontese network boasted over 800 km of rails, Lombardy-Veneto over 500 km, Tuscany over 300km, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies just over 120 km, and the Papal State 101 km. With the momentum of the early 1900s, this network continued to expand exponentially, along with travel speeds that increased until 1939, when the Florence-Milan AV train hit a world record-breaking 203 km/h.

It’s also during this period that some of the most iconic train stations were built in Italy, not just between major cities, but also within them: in 1955 the first metro line equipped with underground stations was inaugurated in Rome, followed by Milan’s in 1964. These stations often reflect the eras of when they were built, which means the more recent ones are a lot more modern than most of Italy’s typically ancient architecture.

There’s a lot of stations in Italy that follow the classic 2-platform format, but there’s also many that really gild the lilies. Here, eight stations that are architectural products of their time, and worth a pause next time you’re hustling through.

Torino Porta Nuova (1864)

Smack in the center of Italy’s first capital, Porta Nuova was the first large Italian station to be expanded after unification and the current third busiest station in Italy. It sits at the end of the bustling Via Roma, directly facing the Palazzo Castello at the other end; the two appear to be in a standoff of who has a grander facade. The former’s is full 19th-century style, with a large, semicircular glazed arch in the middle that continues through to the platforms, of which there are 20.

A terminal station, the 350 high speed trains that come here each day go in and out the same direction; it’s the beginning of the famed Alta Velocità route from Turin-Naples as well as the Turin-Modane route to Lyon and Paris. The Savoy royal family passed through this station often, so a hidden, first class waiting room was built along with it. Named after Francesco Gonin, who painted all the magnificent frescoes that decorate it, the hall can only be visited a few days a year.

Milano Centrale (1931)

Milano Centrale rises out of the city with almost the same majesty as the Duomo–which could fit twice inside this massive station. A magnificent and imposing example of Art Deco and Liberty Style, the building has a compositional perfection typical of Italian Rationalism. Construction was paused due to World War I, and the building was finally inaugurated during the height of the Fascist Era; the ultimate design–namely the facade and the sheer scale–were meant to showcase the dominance of that current regime. There are three large rooms–a carriage gallery, a 40-meter tall atrium, and 215-meter long head gallery–that follow one another before culminating in the 24 platforms, covered by a soaring glass and metal arched roof the size of ten American football fields. At the beginning of the 21st century, the station underwent a 100-million-euro renovation, and numerous shops and restaurants–including Mercato Centrale–service the over 320,000 people who pass through the station daily.

A two-story waiting room connected by marble staircases, called the Sala Reale, was originally designed for the Savoy royal family, then diplomats and traveling royals. As Turin’s equivalent, the sala is only open to the public a few days a year. The ornate rooms have marble statues, ebony furniture, majolica, and frescos as well as wooden inlaid floors that, quite unfortunately, still feature a single swastika, included in anticipation of a possible visit by Adolf Hitler. Even the bathrooms reflect the unsettling vibe of that time, as a secret, hidden escape route was built behind one of the mirrors in case of emergency.

Firenze Santa Maria Novella (1935)

Designed by a group of Florentine architects, Florence’s primary train station is a shining emblem of Rationalism that reflects the canons of modern European architecture from Italy’s Fascist Era; the sleek, Futuristic design was approved by then-leader Mussolini. Even the fonts of the signs call attention to that time, including those left for posterity but are no longer applicable, like POLFER for railway police or LABORATORIO TELEFONI for switchboard operators. The station’s plain sandstone facade was specifically designed so as to not take away from the Gothic Santa Maria Novella church across from it, for which the station was named.

Configured as a horizontal stone monolith with a height much shorter than its counterparts, the interior of the station is quite simple and harmonious, as is navigating it. You can enter from nearly any direction, including underground, where there is also an expansive shopping mall and parking garages. The entire passenger concourse, which runs perpendicular to the station’s 19 platforms, is lined with skylights and without columns or walls, making it feel exceptionally airy and bright. Aside from the main Partenze (Departures), board, you’ll want to look at the large mural of the same name, unveiled in 2006 but painted with Renaissance fresco techniques. Even if you’re not taking a train from Platform 16, head over to peek at a plaque honoring those deported to Nazi concentration camps on March 8th, 1944, as the station was “their last glimpse of Florence before the Holocaust.” Here too, as in Milan and Turin, adjacent to the station is Michelucci’s white marble waiting room called Palazzina Reale, intended to host the king and his family during their short stays in Florence.

Montecatini Terme – Monsummano (1937)

Located within an hour of Florence to the Northwest of the city, the city of Montecatini is well connected to Pisa, Florence, Lucca, Viareggio, La Spezia, and Rome. Recently restored, this small station, built just after Firenze Santa Maria Novella, became necessary given the continuous increase in visitors coming from all over Italy for access to the city’s modern and efficient thermal treatment facilities. With a longitudinal layout, trains pull through the three small platforms of the station. Covered in travertine and porphyry, the building is compact and characterized by a long, semicircular canopy and a tall pentagonal clock tower adorned with fasces–an Ancient Roman weapon made of a bundle of wooden sticks tied with leather strips, representative of the power of life and death. Inside the waiting room, find beam seating and vintage posters hanging on the wooden walls.

Venezia Santa Lucia (1952)

If you want to feel as glamorous as a Bond girl or Angelina Jolie in The Tourist, then you better take the train to Venice. Instead of having to deal with a parking garage, you’ll exit the train station and walk down the steps directly to the Grand Canal. The relatively recent building of this station revolutionized accessibility to the watery city, bringing some 82,000 passengers per day from the mainland right to the water. Twenty-three platforms stand atop the ashes of the church of Santa Lucia, which was demolished in 1860 in the name of progress. Respectful and sober, the stone-clad facade reaches out towards the water through its metal shelter, typical of the railway architecture at the time but looking almost like the secret hideaway for the Avengers. Flanked by two Venetian lions, the structure is low, wide, and entirely Rationalist. A bridge in front of the station links passengers directly to the Santa Croce neighborhood, and then to the rest of Venice. The building is a magnificent example of how modern architecture can fit into a historical context.

The view upon exiting the Venezia Santa Lucia train station

Naples Metro Toledo (2012)

Taking the Metro in Naples is not guaranteed to be a pleasant experience, but getting on or off at the Toledo station certainly is. It’s the most evocative stop along Line 1, not just for the huge, symbolic murals by William Kentridge titled “Ferrovia Centrale per la città di Napoli, 1906 (Naples Procession)”, but also for the stunning mosaic designed by architect Oscar Tusquets. Above the escalators, the station is completely covered in a blue and white mosaic that makes it look like you’re underwater, designed as a metaphor for light and sea. But what’s most spectacular about the scenographic project is the use of light filtering through the station’s many skylights, lighting up the underground even at 50 meters below street level.

Reggio Emilia AV Mediopadana (2013)

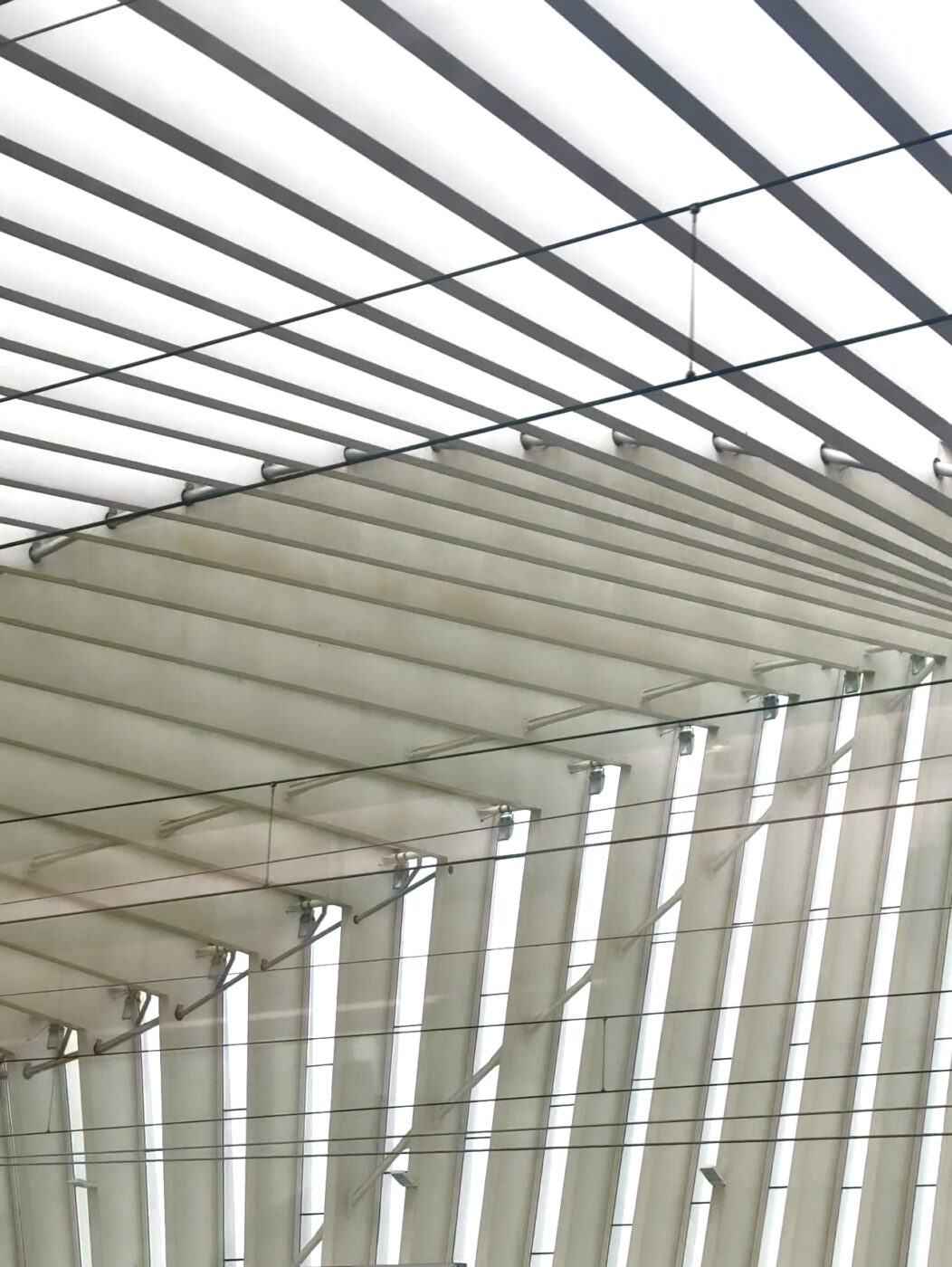

Quite possibly the most jaw-dropping station on this list, the Reggio Emilia AV Mediopadana is part of a larger complex commissioned by the city of Reggio Emilia to better connect the city to the North. The transport hub includes three bridges, regional train stops–running perpendicular and under the elevated AV tracks–and a new highway tollbooth. Designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, the station is a perfect example of his philosophy of architecture: a geometric, long-limbed volume is fragmented into many white segments that seem to chase each other in massive, undulating waves. It’s vast, it’s grand, and it’s stunning, even if just seen from out the window of the Frecciarossa train while taking the Naples–Turin route. There are only two AV platforms and two through tracks, encapsulated within the 483-meter-long glass and white steel roof. It’s significantly less crowded than other stations, and the brilliance of Calatrava alone warrants a stop in this bustling city.

Naples Afragola (2017)

Nicknamed “The Gateway to the South,” this modern station was created by the internationally renowned architect Zaha Hadid, an Iraqi-British architect and artist with an outstanding track record of crazy big projects worldwide. Sinuous like a snake, the station develops transversely with respect to the tracks, with a space of 30,000 square meters across four levels. Design wise, a 400-meter urbanized bridge over the tracks becomes the main passenger corridor–rather than just a connection to the platforms–complete with shops, restaurants, ticket booths, etc., connecting the communities on either side of the station.

The Futuristic interiors are characterized by curved lines and contrasts of white and dark gray. The outside, too, is bright white, and almost looks like a space station. Natural light enhances the space via the long glass skylights throughout the entire station, purposefully designed to be a space for the community of Afragola to gather. With over 60,000 residents in the 18-square-kilometer area, Afragola is a densely populated comune that, until recently, was relatively inaccessible compared to its neighbor, Naples. This new hub of national and regional transport will better connect the region, with 18 pairs of high-speed trains coming through each day accessing the airport, the Turin–Salerno route, Venice, Reggio Calabria, and Napoli Centrale.