It’s a grey day in Rome, a gentle breeze is blowing and the city looks like the set of a 1960s film. It’s already late morning and, having crossed Piazza Farnese, I pass the Peru bar where someone, despite it being lunchtime, is enjoying a breakfast of croissant and cappuccino (beata gioventù!). Walking between the cobblestones and fountains of Rome’s jagged, picturesque streets, I find my gaze caught, not by Rome’s grand facades, but by small oases of chaos: the antique shops, hardware stores and artisans’ workshops that are scattered throughout the city. These are places on the edge of the modern era, steeped in an organised disorder.

I find myself standing in front of a small antique shop, its façade made up of dark wooden frames with a few chips from the passage of time. The window itself is slightly opaque; a thin layer of dust has settled on the surface, with no intention of coming off.

I decide to go in, and, the moment I cross the threshold, a small bell tinkles, announcing my presence. Seemingly fragile porcelain plates are stacked to architecturally-questionable heights. Teacups, long separated from their saucers, create a beautiful tapestry of mishmash. A few vintage signs lie crooked against mid-century armchairs. Unbuffed bureaus hold little treasures: stamps from countries that no longer exist, postcards from 80 years ago, a button from a now-buttonless trench. The shopkeeper is forced to leave his small room at the back–interrupting his lunch or perhaps a particularly engrossing book–to greet me with a small smile. He tells me he is available to help and pretends to fix the first shelf he comes across. He keeps his distance a little so as not to be intrusive, but it only takes asking a simple question for him to delve into an impassioned monologue about all the pieces he sells–and for each one, he has a different story to tell.

His name is Franco; he has a wife and two daughters. He tells me that the shop was his father’s before he inherited it, and year after year he fills it with objects and items that have taken his fancy. In this chaos, I’m not quite sure how Franco ever finds what he’s looking for. And yet somehow he does. There’s an order to the madness–a map that only he knows and that makes the shop uniquely his.

As we chat, I take off my jacket and place it on the first chair I see. I sit on the ladder near the bookcase, and Franco offers me a glass of water. It feels like this shop is an extension of his home, and I realise I am no longer used to surroundings so imbued with human warmth.

I realise that a place is all the more beautiful when there is empathy and emotion, something that awakens our memories. When I enter places like Franco’s shop, the smell recalls my childhood: I see my grandparents’ house again, the bookcase they had, their favourite coat. It is the nostalgic smell of dust.

It reminds me of a scene in Paolo Sorrentino’s film La Grande Bellezza. When the protagonist Jep Gambardella is asked what he likes best, he replies: “the smell of old people’s homes.” It’s a phrase written by the director, but which belongs to all of us: a truth in which it is impossible not to recognise oneself. Lived moments continue to exist in memories, pieces of paper, paintings, books, toys, maps, photographs… Physical remnants of the passing of time.

I leave Franco’s and continue on my long walk, moving away from the better-known historic centre and arriving in Monti. It’s an area that was unknown to tourists until a few years ago, but which has undergone a transformation in recent years–and is now filled with trendy clubs, sushi restaurants and souvenir shops. I pass the central square of Piazza della Madonna dei Monti, take one of the two small streets surrounding the bar in front of the fountain, and let my instinct guide me without thinking too much about where I am going.

After not even ten minutes, I am at the end of Via dei Capocci, at the junction with Via Panisperna, and on the left is one of my favourite places in the whole city: a carpenter’s workshop, with no sign and perhaps no real official name other than “Falegnameria e Restauro Rione Monti.”

The first time I came across this shop was in my early years of driving. I was lost and trying to figure out how to get home, with only the “Tuttocittà” to help me–a paper road map of Rome from before the days of Google Maps. I had taken Via dei Capocci in a hurry, but I can still recall how, in a few seconds, all my nerves dissipated as I spotted a carpenter working on the doorstep of his workshop. Behind him, inside the shop, there was–and still is–a mountain of tools, boards, scraps and dust.

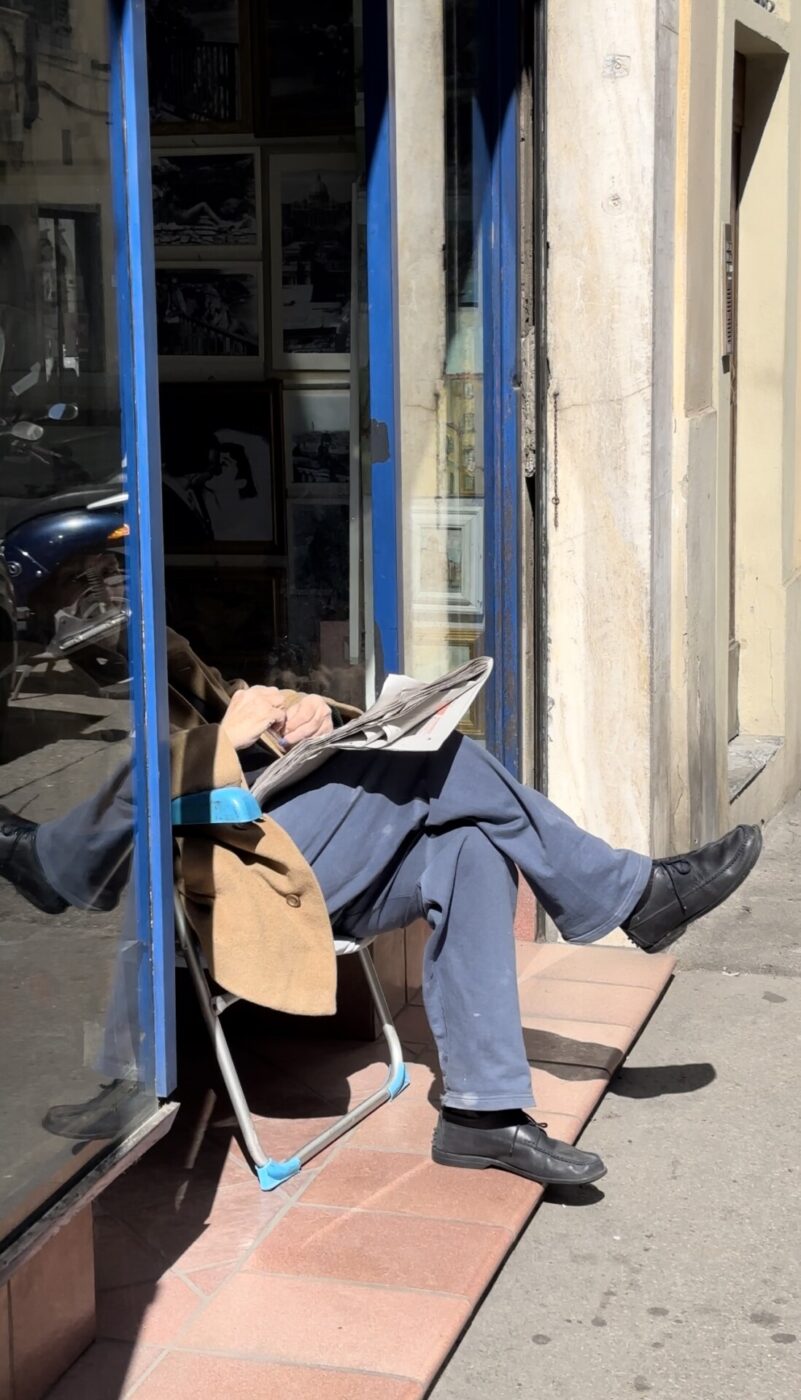

On sunny days you can find him there, out on the street, unconcerned with passers-by and fully absorbed in his work. It’s a scene that is out of its time, left over from a distant period that in one way or another still feels close to us. Old, scarred, lived-in, forgotten and above all, completely chaotic. Albert Einstein once said, “If a cluttered desk is a sign of a cluttered mind, what, then, is an empty desk a sign of?” Perhaps he too had observed such an artisan.

Going back to that noble mess every now and then and supporting these small businesses is not only a way to help these owners and small shopkeepers, but an opportunity to not get lost in the glittering veneer of artefact and mass production of the modern day. These days, minimalism is all the rage. “Scandinavian-style” aesthetic dominates, and carbon copy spots–where everything is clean, simple and shiny–are everywhere. (Though it must be said that Italians interpret this aesthetic quite badly.) Somehow it feels less exhausting to be amid the chaos, the imperfection, of these old, old Italian shops. I believe that they are where we feel most in our element: simply human beings, in a profoundly human environment.