“There is a Florence that is a destination for a particular double-sided homosexual jet set that finds, on one hand, in Radclyffe Hall, and on the other in Oscar Wilde, its protective deities; a Florence that will never extinguish its dandy myth.”

These are the words of Pier Vittorio Tondelli, a homosexual writer who died of AIDS in 1991. Tondelli was born in Correggio, but claims that Florence was the place of his initiation into the life and death of the world in the book “Un weekend post moderno” (“A Postmodern Weekend”), published in 1990. When Tondelli writes of the Florentine gay world, he opens it up to something bigger than his personal point of view, instead painting it as a collective experience: “In Florence…it is still possible to trace and live something that other cities have never had: the center.” This “center” is not the physical grid of a modern Italian city, like Milan, created by the military. Rather, it is an extravagant map: a cluster of alleys packed like intertwined serpents in a box made up of provocative clubs and underground venues. A queer Babylon, overturned like Dante’s map of hell, where everyone could find and be themselves.

Three decades later, and the queer scene in Florence–as it is throughout most of Italy–is still very much underground. Where the identities of other global cities like London, Berlin, and New York are almost inseparable from their queer communities, Florence’s gay scene thrums from below, cloaked in darkness but glimmering, refusing to be extinguished.

Artistic director of the Florence Queer Festival, Bruno Casini, was the organizer of more than a few memorable events: a sort of Dante’s Charon ferryman of the Florentine queer scene. Leading me around town, he tells me what life was like when Florence was a shimmering icon of gay debauchery.

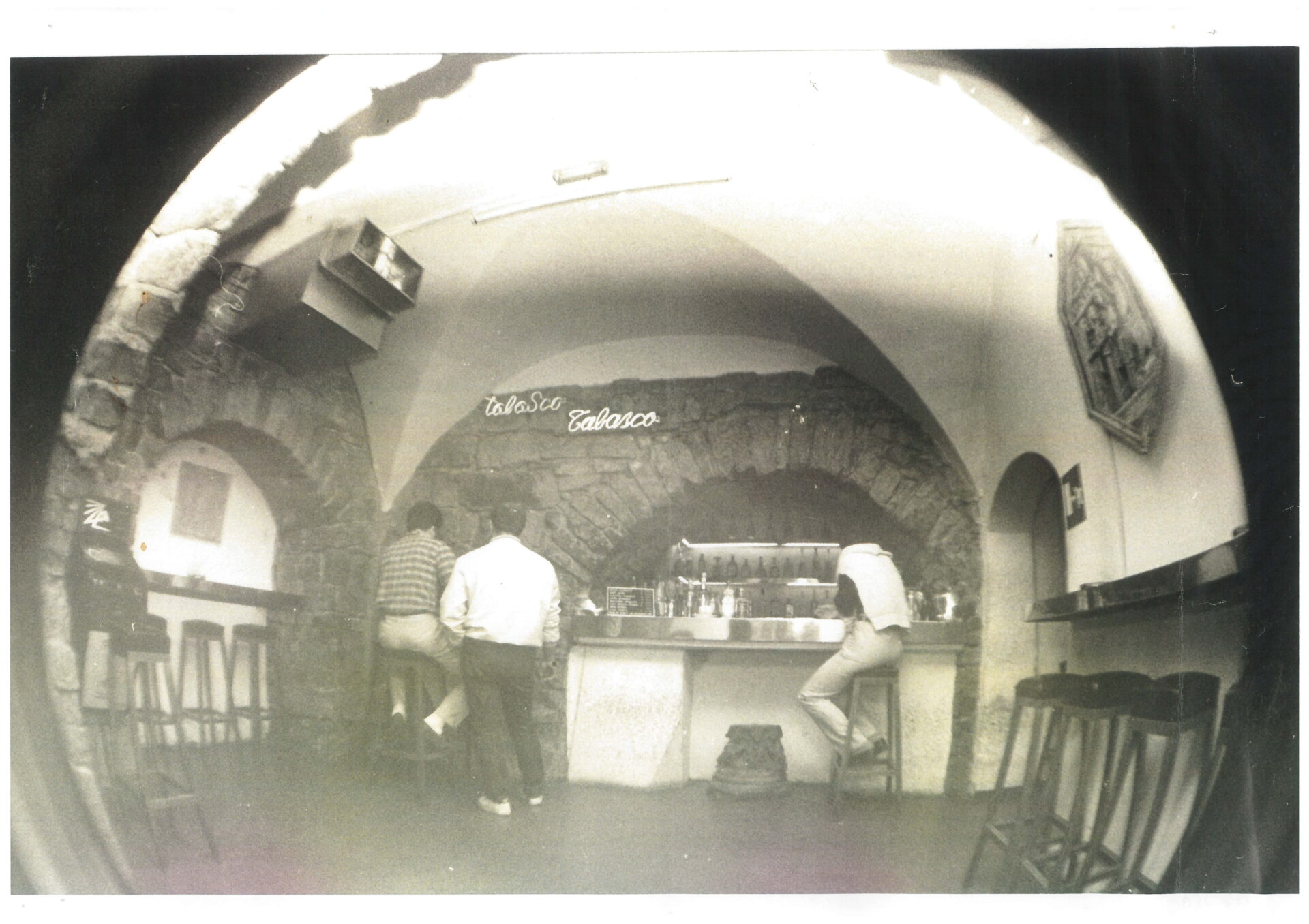

Tabasco, a gay club in Piazza Santa Cecilia, opened in 1974 as a cultural gathering place before transforming into something else in 1978: “With Saturday Night Fever, it also became a dance floor and disco, becoming one of the most frequented places of international gay tourism,” he explains, as we walk past the padlocked door. The venue closed in 2008, but its ghost is still palpable on the street near Palazzo della Signoria. Night events at Tabasco were cozy, with a lot of necessary privacy: at that time, many famous men (writers, politicians) met in the darkness and enjoyed the club’s vibrant atmosphere. Luca Locati Luciani, an expert on Florence’s queer and pop scene, echoes Bruno: “From Tabasco onwards, Florence became a gay city, recognized internationally as a status symbol.”

Tabasco founders Marco Bagnai and Marcello Salvietti also founded Crisco, the first gay cruising club that takes its name from the famous American margarine used for lubrication. It’s the only such venue still open today in Florence. Apart from the bubble typeface logo that maintains the excitement and youthfulness of its years past, there is nothing of what it used to be. If Tabasco was the cultural meeting place of the homosexual scene, then Crisco was the delirium of an infernal, kinky circle. With its memorable dark room, Bruno remembers: “It was a bit rough, a bit extreme, it looked like a prison. The reference was to Jean Genet, to the culture of slave and master.”

Tabasco in the 1980s

Crisco Club poster

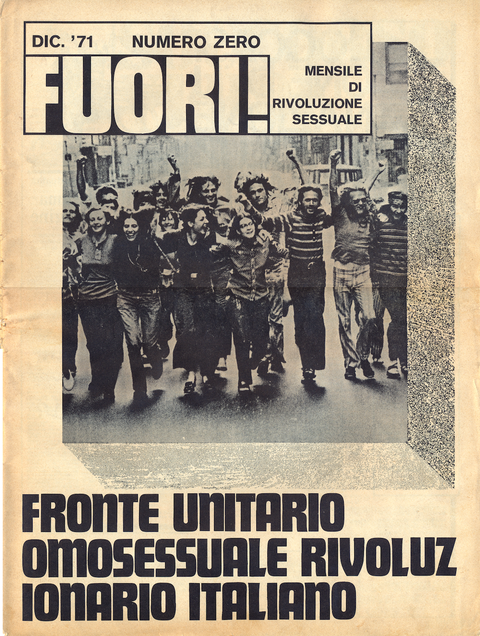

Florence aimed for excess, hedonism, and a queer scene that was such in every sense of the word, standing in opposition to all that was hetero, patriarchal, cisgender, and straight-edge. “Homosexuality is objectively a particularly persecuted and condemned form, especially because it represents pure eroticism, that is not institutionalized, not controllable, elusive to the primacy of genital heterosexuality, and not reducible like this to ‘sex’ for procreation and, therefore, to the patriarchal family,” wrote the homosexuals of the first Italian gay magazine ever, FUORI!, at the launch of their issue #0 in 1971.

These were difficult years that need to be read in a broader context. In the 1960s, identifying as “homosexual” was like the metonymy used by Dante Alighieri: it was an umbrella term for the undefinable whole, and yet was cataloged by hetero and patriarchal society with dehumanizing names such as “invert” and “third sex.” In those days, naming was important: it meant coming out after years of strong stigmatization. Luca Locati Luciani, founder of the Aldo Mieli Documentation Center and a valuable archivist of Italy’s LGBT+ community, explains that, on the eve of the 1970s, Florence became the scene of a real roundup.

It was May, 1969, a month before the Stonewall riots, and the police carried out a raid in the areas of Cascine, Piazza Vittorio Veneto, Albereta, and Lungarno del Tempio: it was the map of the cruising scene in Florence, against which, as the daily newspaper La Nazione writes, there was “a war on homosexuals for more than evident reasons of public morality.” After the raid, the queer community wrote a letter against “Nazi-Fascist persecutions, police checks, and racist speculation by the press,” and publicly expressed their dissent. Gay, lesbian, and trans people took to the streets to assert their existence. These were years in which the press leant towards violence, as La Stampa in Turin in 1971 wrote: “Poor homosexuals, so psychotic, and neurotic, and unhappy.” On the contrary, in Florence, to paraphrase the editorial of issue #0 of FUORI!, the queer community was “dynamic and passionate.”

Florence was the birthplace of prolific characters, icons who pushed boundaries and left outsized marks. If conservatives were going to accuse queer folk of being immoral, then the queer community would show them just how far they could go. The Banana Moon, which opened in 1977, a year before the historic Pisa pride event of 1978, serves as a bridge and is a key place to understand Florence’s queer history. It was a queer venue before the term queer existed, proto-fluid, because of its varied clientele that blended people of different classes and tastes. Today, there is only a green door to remember what was, for Bruno, a disruptive and necessary place: “We organized concerts, with performer Ivan Cattaneo and Alfredo Cohen, pioneer of gay cabaret. Among music producers, there was Franco Battiato with his record ‘Come barchette dentro un tram’, released in 1977 with the introduction by Fernanda Pivano, mother of the Italian beat generation.” Bruno, full of nostalgia, points to the civic number and thinks back to that city of Dite. It was the place where Mario Mieli, one of the founders of the Italian homosexual front, and among the first gay activists, shocked an entire audience by defecating on stage and serving his feces. Florence’s creativity of the following decades begins here. A creativity made up of sex clubs, but also of liquid, shiny, and flowy places, like the silks and garbage bags worn by Mieli to impress the audience with shocking performances.

Leigh Bowery, the Melbourne artist and drag queen, introduced the exuberance of queerness to the streets of Florence. Bowery lived in Florence for six months, scandalizing the city with his performances and post-punk style. In Florence, Bowery came into contact with I ragazzi del Bopper, a queer collective born in the 1980s that anticipated that culture of extravaganza that would explode ten years later. Their parties were memorable, outrageous, and boisterous. At their “pagan feast,” guests were greeted with pieces of cow meat hanging and dripping blood. “Once their DJ, Asso, peed on people, and many mistook it for champagne.” This congregation of alternatives turned Florence into a London dream: inspired by Bowery’s transformations, it brought with it a disruptive, glittery, and light-hearted hedonism, that Bruno calls “the aesthetics of the impossible.”

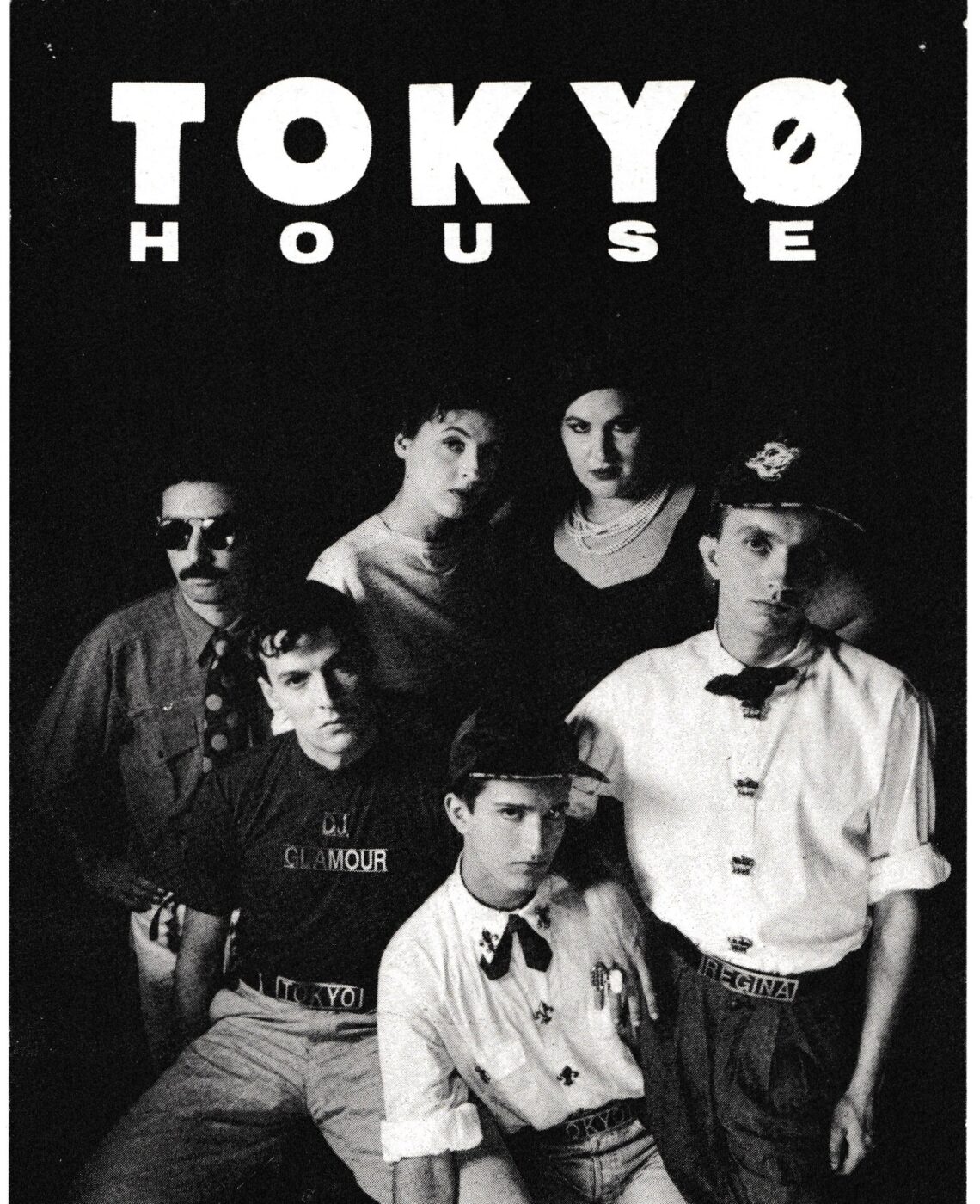

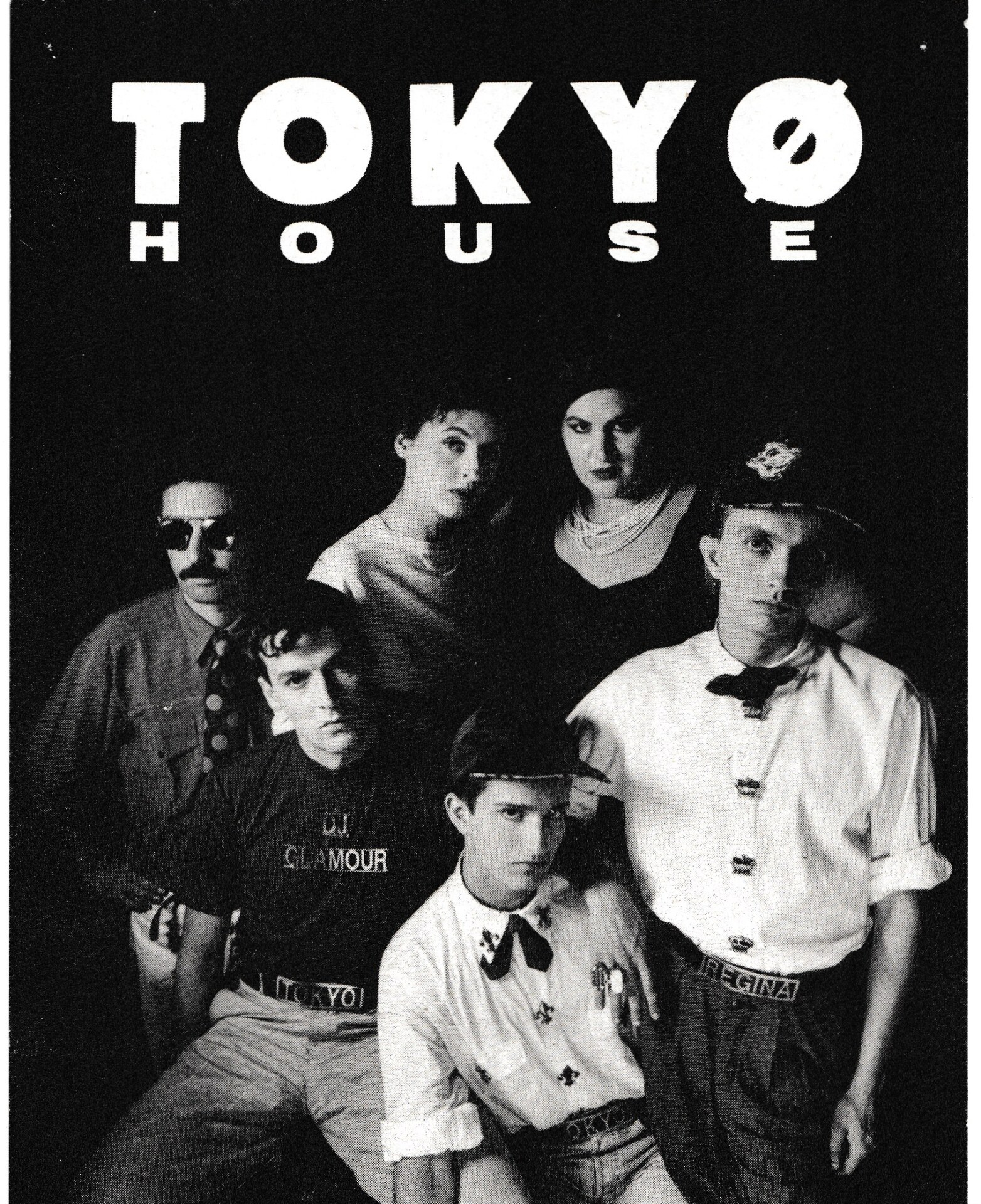

In this extravagant slice of Florence, even frivolity was a political act. “We lived the heritage of the counterculture of the 60s: there was no idea that politics was different from life. We enjoyed an incredible bubble; we had fun even when, outside in the world of bureaucracy, debt was rising to crazy levels,” shares Stefano Bonamici, artistic director of the countercultural collective known as Tokyo Production. Born in the 1980s, on the crest of the Florentine queer wave, this collective channeled the energies of the homosexual world from the tombs of public morality into crazy parties. “You found everything from punks to preppies, and when they left, they were all friends–naked, ties gone, shirts unbuttoned,” recalls Stefano. Embracing queerness was possible in Florence, a city that, more than Milan, breathed fashion and international culture.” At the first event we organized, on January 5th, 1986, just two of the many people in attendance were Italian model Dalila Di Lazzaro and French designer Jean-Paul Gaultier.”

Tokyo House

Florence became a crossroads, a lovechild of London and Berlin: “All it took was word of mouth,” explains Stefano, “And then, to make it a global city, there is the fashion universe of Pitti. Enrico Coveri brings an international staff to the city of Florence, filling it with young people from all over the world.”

Speaking of fashion, Bruno leads me to Via Roma, where the flagship of Luisaviaroma–once a boutique by Andrea Panconesi, now a global band–stands. Today, the LED lights overpower the memory of the windows that reflected elegance, a symbol of boundless carelessness. Owner Panconesi, Bruno continues, deserves credit for “giving the classic boutique an international formula of fashion, oriented towards experimentation, and aimed at risk-taking.” The fashion imported in Luisaviaroma shaped queer imagery in Florence.

Florence’s gay street, Borgo Santa Croce, is now unrecognizable without its rainbow flags. During the day, it’s a narrow alleyway that expands towards the square where the homonymous basilica stands. One must wait until evening to see the neon light of Quelo Bar turn on as Katia, the owner, opens the doors to all: “There is a diverse clientele, certainly LGBTQ+,” she explains with a simple and sincere smile. Next door is Piccolo Café, the meeting point of the Florentine rainbow community. It is closed until sunset, when the cobblestoned street, scraped by the luggage of hit-and-run tourists, turns into an open-air patio.

In Piazza Santa Croce, a more solemn legacy looms. In the 1990s, the Gothic architecture of the church was the setting for the opening of the Seventh International Conference on AIDS. It was June, 1991, and, for the first time, an Italian city hosted doctors, researchers, speakers, and people living with HIV. The still-skeptical press called it ”The Conference of Hope”, and were worried about “the AIDS people: thousands of sick or potentially sick people who will come to Florence.” The photo in front of the Basilica with the so-called “quilt of names”–the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt–propped up by scaffolding, tells the story better than any text, of the social closure and stigmatization due to reasons of “public morality,” or, more accurately, prejudice.

Aids quilt at the Conferenza sull'Aids a Firenze (1991). Photo courtesy of Giovanni Rodella.

Like the people who drive them, those that still stand with Florence’s queer venues are resilient against waves of prejudice, inflation, and changing politics. A temple of nostalgia, still full of life, is Contempo Records, a historic record store inaugurated in 1979 that also worked as an independent record label, printing the first records of Litfiba, Neon, Diaframma, and the new wave of Florence. We are greeted by Alessandro Nannucci, with a long beard and sharp gaze, who is one of the first rock leather enthusiasts in Florence: “Even today, Contempo is a space where there is a lot of rare vinyl, which still attracts a rainbow audience interested in disco vinyl. The best-sellers are the first vinyl records of the Village People,” explains music-expert Bruno, who considers it a must-visit spot. Disco was also this: the soundtrack of a new community, the anthem of a revolution made on dance floors and in the squares of global protest, as the Gay Liberation Front of 1969 in New York recalls.

There may not be much of Florence’s glittering past that remains, but what there is displays an enduring legacy that perfectly encapsulates the counterculture of the city itself. A city that rediscovered what it had always been in the queer community: a construction site of a slippery, never-static, jagged identity, battered by the winds of politics and fashion. A fractured identity, but one that remains standing. Like the rustication of the facade of Palazzo della Signoria.