In the heart of Emilia Romagna there’s a delicacy that always rhymes with celebrations. It’s called zampone and while its description might turn picky eaters’ stomachs, I promise you it’s beyond delicious. The name comes from zampa, meaning paw; fitting, for the feast food is an entire foreleg of a pig, stuffed with a pork mixture of lean and fatty cuts, coarsely ground with pork rind, and seasoned with spices like pepper, cloves, cinnamon, and nutmeg. The hoof is left on.

The flavor is savory, with a hint of sweetness thanks to the spices, with a tender and jelly-like texture that manages to taste creamy but not mushy or sticky. A good-quality zampone has a bright pink interior and a mild aroma. It should slice easily without falling apart, the ring of pork skin creating a sort of wrapper around each slice. Cooked slowly in the zamponiera (a sleek, elongated aluminum pot made specifically for this purpose) and served with lentils (for good luck) and mashed potatoes, zampone is never missing from a Christmas or New Year’s table in the region.

If you ask my mother, the pork foot is the best part.

Zampone vs. Cotechino

While zampone is mostly known in Emilia-Romagna, its “brother” cotechino is more widespread across Italy, though less of a star during festive meals. Let’s clear up the difference: though both salumi insaccati (there’s no exact English translation, though sausage comes relatively close) are made from a similar mixture of finely ground pork, pork skin, and spices, what sets the two apart is the casing–zampone is encased in the pig’s front trotter, while cotechino is stuffed into intestines, either natural or artificial. Where zampone gets a leg up, if you will, is in the cooking, when the skin of the trotter melts, giving zampone a more gelatinous texture and a richer, more unctuous flavor than cotechino. This mouthfeel tends to divide the holiday table into two camps: those who leave the skin aside (like myself) and those who happily devour not only theirs, but everyone else’s portions too—usually the adults.

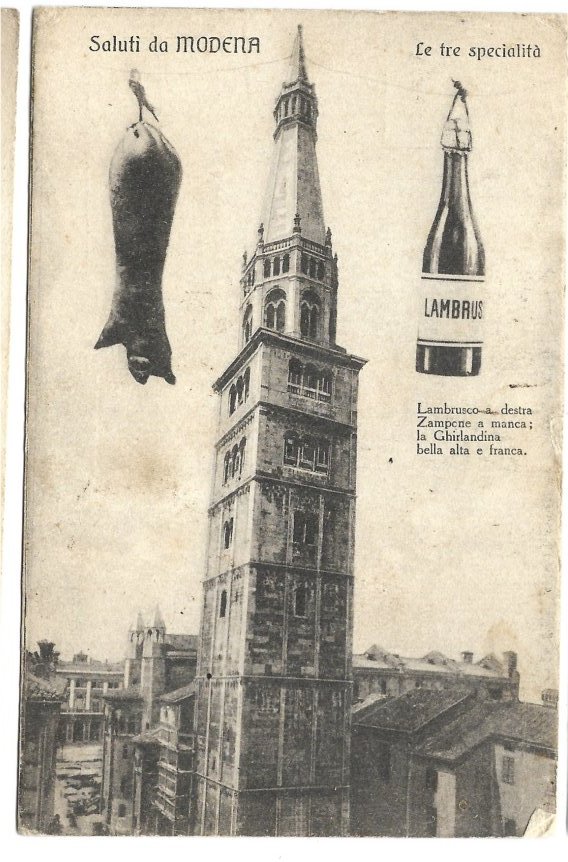

A vintage Modenese card, featuring Lambrusco on the right and Zampone on the left.

The Origin Story: Mirandola, 1511

One of the key towns in the Emilia-Romagnan province of Modena is Mirandola, home to 24,000 people and known as both a biomedical hub as well as the birthplace of philosopher Pico della Mirandola… and zampone. Legend has it that the celebratory trotter was invented here in 1511 during a siege by Pope Julius II’s troops. As hunger set in, the townspeople, left with little more than pigs to eat, decided to slaughter them and preserve the meat in trotters and intestines rather than let the enemy have them. The idea supposedly came from Papazzone, one of the personal chefs of philosopher Pico himself.

Having survived the conquest of Mirandola, zampone and cotechino quickly gained fame in the region beyond Modena, becoming iconic delicacies linked to the rural tradition of slaughtering pigs on December 13th, St. Lucia’s Day; the colder weather provided ideal conditions for curing and preserving the meat over the winter months. And, by the late 19th century, the transformation of two pioneering butcher shops, Frigeri and Bellentani, into larger establishments helped these products reach even further markets.

After WWII’s industrial advancements, pre-cooked zampone became widely available, and since 1999, IGP certification has protected the ancient recipes of zampone and cotechino, ensuring traditional methods are respected. For example, the pork mix must be ground to a specific size, blended under vacuum or normal pressure, and encased in the pig’s front trotter, hoof included. Fresh zampone must undergo an air-drying process, while pre-cooked versions are sealed and heat-processed to maintain stability. The Consorzio Zampone and Cotechino Modena IGP, founded in 2001, preserves this legacy, safeguarding quality and promoting these specialties worldwide.

Food historian Alberto Grandi, whose debunking of Italian food myths went viral after an interview with the Financial Times, however, has not left the story of zampone unscathed. “No, it’s not true,” he has claimed. “The origins of zampone are much more recent. It’s largely an industrial product, only feasible in the 1950s or 60s—not more than seventy years ago. Giulio II and Pico della Mirandola were long gone by then.”

Regardless of how old they may or may not be, zampone and cotechino have cemented their status as “traditional” dishes for Christmas and New Year’s, thanks in part to the fact that hearty winter foods like these have long symbolized abundance and prosperity.

Zampone for sale in the Italian grocery store, with a stamp of approval by the Consorzio

From Local Butchers to Pre-Cooked Convenience

As the colder weather sets in, you can find pre-cooked zampone in most supermarkets—even in some delis abroad—but for fresh, raw zampone, you’ll need to visit a butcher in Modena or the Bassa Modenese. Since 1979, Lorenzo, owner of Salumeria Mussatti just 10 km from Mirandola, has been making his own Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena, along with cured meats and fresh zampone during the winter.

“Zampone is the emblem of our cuisine,” he tells me, before explaining that “a truly good zampone is made by grinding the pig’s lean parts, like the shoulder, with fatty cuts like the throat, and adding a bit of salt, pepper, and garlic. Fresh zampone needs to cook for at least three hours over low heat in water.” Like the “true connoisseurs”, he always eats the hooves; “the best part,” he affirms. You can find Lorenzo and his family’s stall at many local markets in the area.

If convenience is what you’re after though, pre-cooked zampone is a great option. Just remove the pouch from the cardboard packaging, submerge it in a pot of cold water, bring to a boil, and let it simmer for about 30 minutes. One of the most beloved producers of pre-cooked zampone from the Bassa Modenese area is Salumificio Palmieri, in business since 1919.

"The Emilia Burger" at Franceschetta58, featuring a Chianina and cotechino patty; Photo by Marco Poderi

Cheffy Takes on the Zampone

While traditionally zampone is enjoyed sliced with a side of mashed potatoes and lentils for good luck, you can sometimes find it ground and turned into a ragù for pasta or lasagna. And some chefs in Modena don’t limit themselves to even that.

One such chef is Luca Marchini, of the one-star Michelin restaurant L’Erba del Re in Modena city center. His take on this traditional dish sees zampone turned into a burger, seared, and served between two slices of caramelized pear bread. The plate is completed with Emilia-style salsa verde and horseradish sauce.

When I ask about the inspiration behind his reinterpretation, Chef Marchini explains, “I live and work in a part of Emilia where typical products like zampone have a strong tradition. There’s always an interest in reinterpreting local recipes, showing how they can be enhanced with different approaches rather than sticking purely to tradition.”

“In this recipe, I want to present zampone in its classic preparation, accompanied by two sauces that are part of our culture,” he continues. “The idea was to incorporate this combination into a modern format like a burger while keeping the textures, flavors, and aromas of the zampone and its sauces intact. It’s a dish that embodies classic comfort food, but presented in a modern format—a bite that encompasses roots and innovation.”

Zampone is making waves beyond tradition, and Marchini is not the only one. At Zelmira in Modena’s picturesque Piazzetta San Giacomo, you can find zampone and potato croquettes with Parmigiano foam and friggione, a hot side dish made in Bologna with crushed tomato and chopped onions cooked for hours. Over at Franceschetta58, Massimo Bottura has signed the Emilia Burger, featuring a Chianina and cotechino patty, 24-month aged Parmigiano Reggiano, and a bright salsa verde made with parsley, capers, anchovies, and mayo, all finished with a balsamic glaze.

But the good old pairing of zampone and mashed potatoes still rules during winter times–especially at Christmas lunch. In my family, zampone is a cherished holiday treat, gifted to my father by his former patients, slices of the stuff shining amid Spanish beans, buttered spinach with Parmigiano, mashed potatoes, and lentils. No special tips or techniques—just tradition.