Hand me any Italian menu. Its words are all I need to make an x-ray of what I’m going to eat, how it will be plated, what the chef’s culinary references are, or what the owner’s vague wishes are–whether trendy, 10 years too late, a tourist trap, or a restaurant patronized solely by locals. It’s no divinatory art, just decades of empirical knowledge.

Cooking has its own trends. Exactly like fashion, music, and the like, what we eat also changes according to the (metaphorical) season. As such, the recipes, ingredients, and way we talk about and describe food evolve too. Although Italy may seem (and is) anchored to its gastronomic past, there has been plenty of evolution. Tables specializing in local specialties coexist with fine dining restaurants and contemporary trattorias in line with the latest international trends, but also lurking is the risk of running into a dystopian projection of traditional cuisine. Here in Italy, knowing how to read restaurant menus helps you know whether you’ll eat well beyond the recipes, traditional or not.

This is a brief dictionary of words you should look at with suspicion, with underlying meanings and ingredients In and others Out. Because life is too short to eat bad food–least of all in Italy.

Il “nostro” (“our”)

Il nostro (“our”) is lying in wait around every table corner in Italy: “our [insert any plate here]” could be a famous house dish, and a great one, or it could be an unsolicited “creative” version. Let’s use the most bastardized of desserts as a case study. A tiramisù is a tiramisù: ladyfingers, coffee, mascarpone cream. It’s not an elaborate dessert, and its goodness lies precisely in its home-cooked simplicity. At home, it’s made in a large pan; in trattorias, it often still arrives that way, a small square scooped out from the tray. In nicer places, it’s served in a single portion, and those who want to make it fancy put it in a martini glass. If you read on the menu, however, “our” tiramisù, be warned. It might come with an unfortunate twist, an imaginative interpretation that arrives as a frilly dessert that has little to do with the original. Better to ask for clarification: “how do you make your tiramisù?”

Rucola, salmone, fragola, panna, e champagne (Arugula, salmon, strawberries, cream, and champagne)

These were words of the wonderful 80s. Arugula topped every meat you can imagine, pennette with cream and vodka was a modern dish, strawberry and champagne risotto raged, and the ultimate cool course was bis (or even tris) di primi, two (or three) different types of pasta served together. Now, as part of a greater trend for nostalgia, many modern chefs are rehashing these memories to make more of them, though in small towns or touristy areas plates like these may be heirlooms, unchanged since that decade. Eat at your own risk.

Zenzero, frutto della passione, polvere di liquirizia, glassa al balsamico (Ginger, passion fruit, licorice powder, balsamic glaze)

As we entered the 1990s, Italian cuisine became more “exotic” and began to experiment with ingredients from distant lands; you might have found the likes of licorice powder on pasta or passion fruit with raw fish. And then there was the overly sweetened balsamic glaze that everyone abroad still uses, but in Italy has more or less remained the preserve of B-list restaurants. Finishing every plate with this glaze is the reddest of flags (unless you’re in Modena and it’s real Aceto Balsamico).

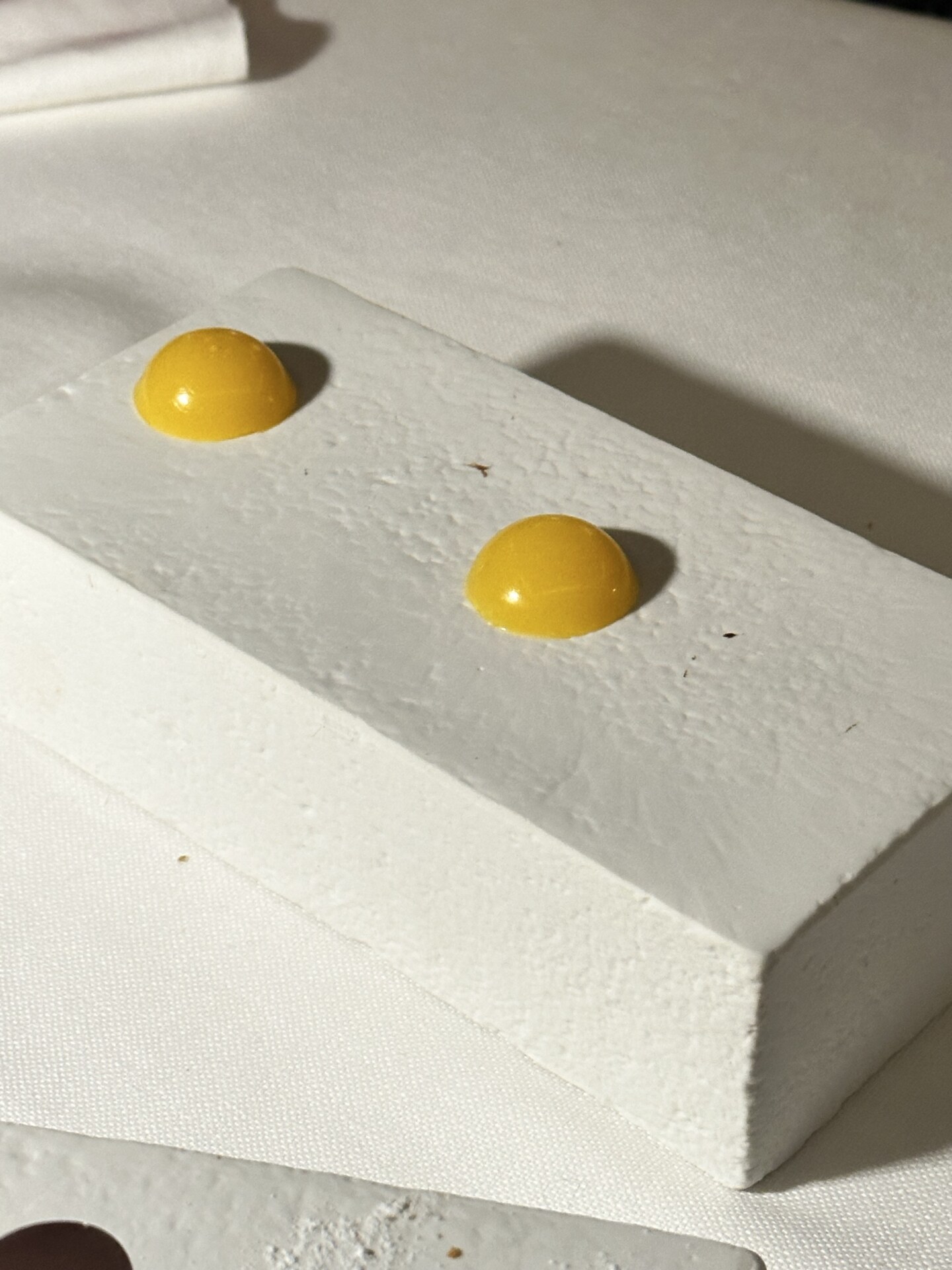

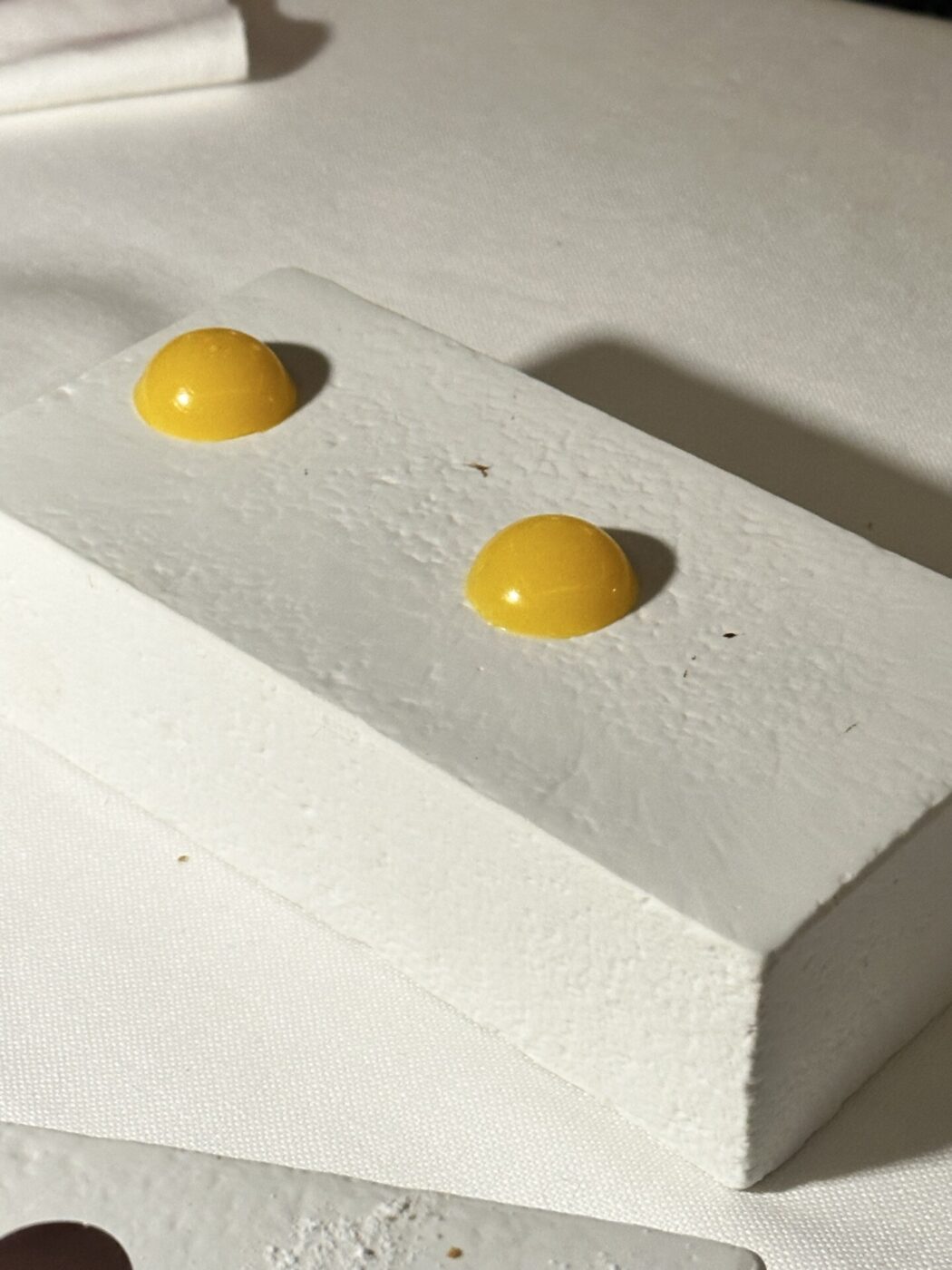

Aria, spugna, sferificazioni (Air, sponge, spherifications)

At the turn of the 2000s, the restaurant industry was revolutionized by Spanish molecular cuisine, a true epochal change in the use of innovative techniques that raged for better but also for worse in our country. Twenty years have passed since then, and the idea of serving Parmesan air, pesto sponges, or spherified oil is, let’s just say, out of its time. Those very useful techniques are used in many kitchens, but certainly not to impress, so they don’t end up explicitly declared on menus. If you find these words, there’s a good chance that they, rather than represent innovation, make ostentation of a cultural rearguard.

Lasagnetta, prosecchino, spaghettino

Diminutives (-etta, -ino) make these dishes seem cuter. Until a decade ago, they were cool! They were all the rage! It’s quite possible these were the culinary effects of the Tumblr-induced twee era of the late 2000s and early 2010s. All too often a diminutive just signals a mignon version of a great classic, lightened even in taste.

Scomposta, destrutturato (Deconstructed)

From the Spanish avant-garde, we borrowed another fashion: deconstruction. Instead of serving the recipe as it should be, the elements are arranged separately, leaving the guest the honor of assembling them. This trend originated as a desire to enhance the feeling of the “individual”, giving the guest “freedom” to compose the dish to their liking, but it left behind a trail of deconstructed parmigiane and tiramisù. Eggplant on one side, sauce on the other, a savoiardo there, cream there, cocoa powder in between. Deconstructed leads, without fail, to a much more disappointing result than the original.

Bruciato, fermentato, affumicato (Burnt, fermented, smoked)

Seasonal, local, sustainable: these are the contemporary mantras, but today we are also in a phase of smoking, barbecuing, direct cooking, and fermentations such as pickles, miso, garum, sourdough bread, and raw milk cheeses. Restaurants are experimenting with exclusively plant-based menus or with mild appearances of oily fish and matured meats from old cows. In establishments that are more inspired by classic Italian cuisine, however, mammoth-portioned meats in the dining room, desserts by the cart, and great traditional recipes are back. Doing all these well is a great thing, but beware of places that lean into burning, fermenting, and smoking for the sake of the trend–or you might end up with a menu that seems to evoke scamorza affumicata plate after plate.

Long story short: it’s best to avoid creative experiments in Italy, like what I recently saw offered in a provincial trattoria–a risottino with peaches, shrimp, licorice powder, and mint leaves. Needless to say, I did not order it.