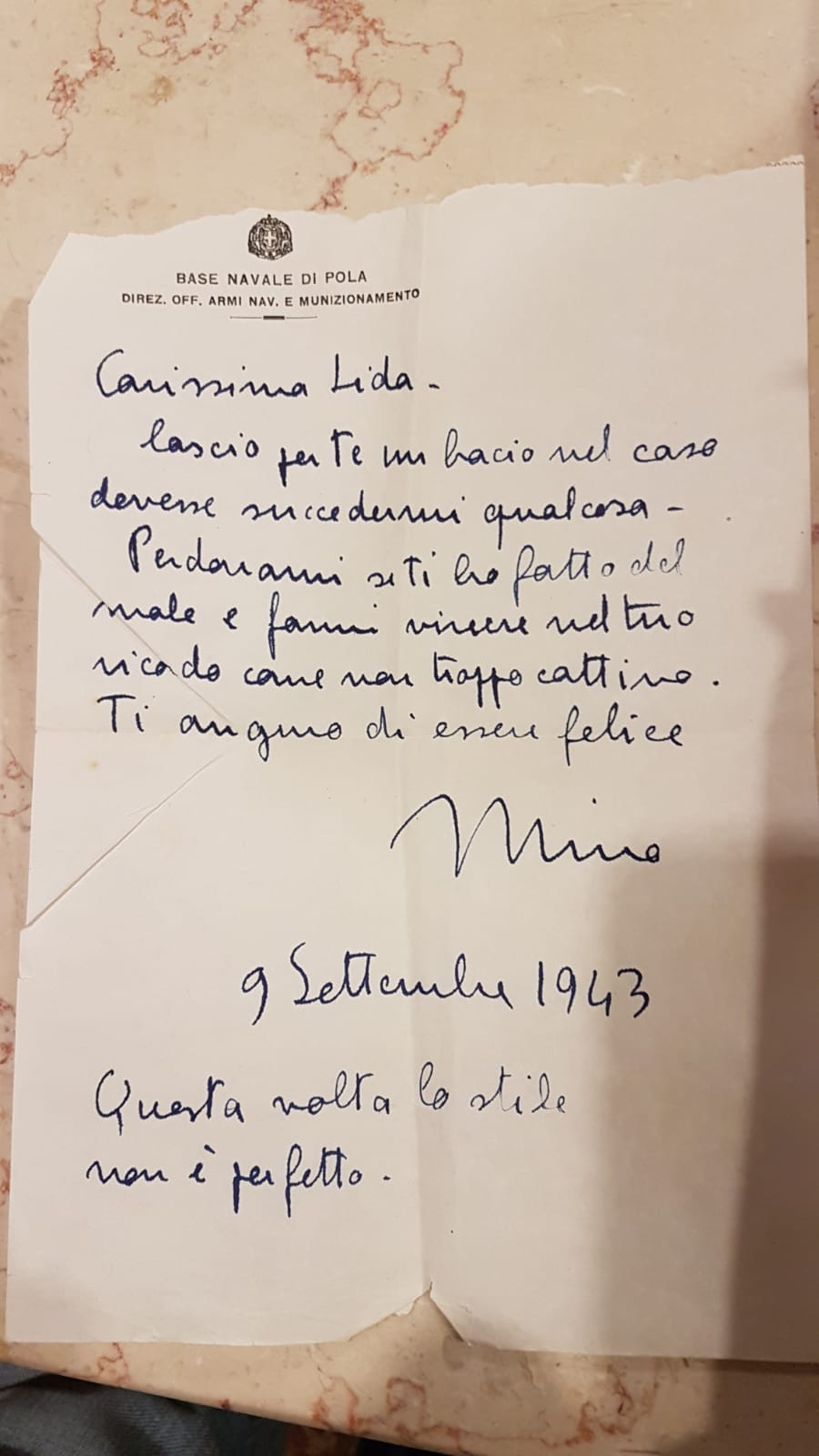

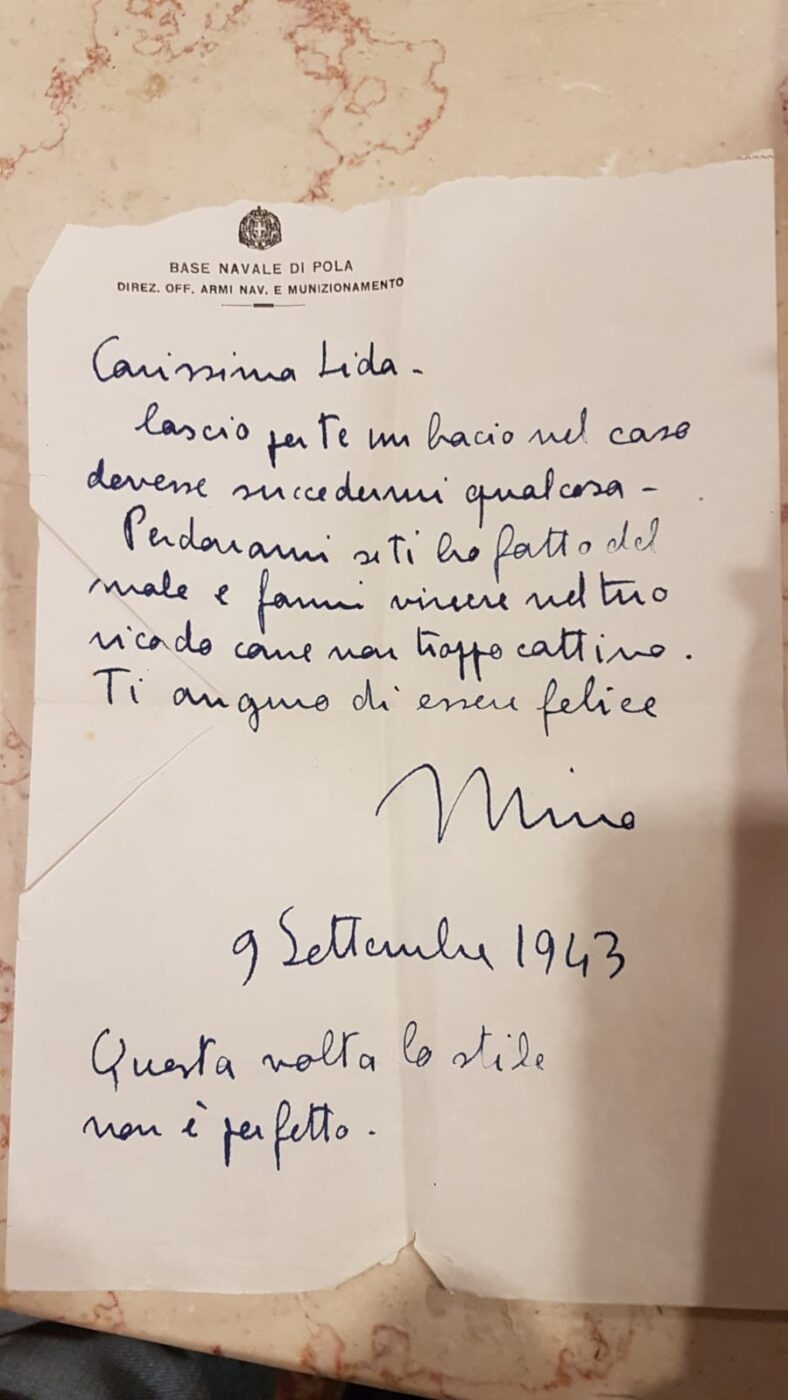

A few words scribbled on a piece of paper, of which the letterhead reads “Base Navale di Pola”–Pola Navy Base in Istria. They were written in a rush, but the calligraphy is precise, honest, sincere. My grandfather scribbled those sentences on September 9th, 1943, right after the armistice, as he was about to be deported to Germany by Nazi soldiers. He thought they would be his last words to my grandmother, who, at the time, had been his fiancé for a few months; they were both in their twenties. Today, 70 years later, the paper carries the burden of time: it’s discolored a little, turned a bit yellow, but the words are still vivid. A physical reminder, kept in a box at my dad’s house, that words matter. Hundreds of entangled words, sentences, pages, put together, become keepers of entire histories. My grandfather’s note is just one piece of the painful history of the exodus from Istria, and language is at the heart of this story–as both a protagonist, a reminder, and a result of pain, struggle, division, and rebirth.

Pola, where my grandfather was stationed in the Navy, is an ancient city in the middle of Istria, that peninsula below Trieste sandwiched between the Trieste Gulf and the Kvarner Gulf. The largest peninsula in the Adriatic, Istria is today divided into and administered by three different nations: Italy, Slovenia, and Croatia, the latter of which accounts for 89% of the peninsula’s 3,160 km2. Visit it one or a thousand times, and you’ll be equally impressed by its colors: the red of the soil, the blue of the water, the lavish green of the hills, and the light, intense white of the ever-present clouds. The smell, driving around the countryside, is that of olives and dry earth. Olive trees, indeed, appear in hundreds after every curve, interspersed with vineyards; the roads proceed sweet and gentle towards the sea, following the pace of hills and bays.

The first appearance of human life in Istria dates back to the Lower Palaeolithic era. Then, from the 11th century B.C., Istria was inhabited by the Histri, a prehistoric Illyrian tribe after which the peninsula took its name: they can be considered the original Istrian population. After a series of wars, between 178 and 177 BC, the Romans took over and founded the port of Pietas Iulia; today that’s Pola. But for almost 600 years, from 1374 to 1918, Istria lay wholly under Italy. And it’s a heritage that has been built into the cities’ walls, streets, architecture. A popular, old Istrian folk song goes “anche le pietre parlano Italiano” (“even the rocks speak Italian”). The Italian language is buried deep in the very fabric of Istria.

As most borderlands, Istria is a place where heritages, languages, cultures overlap. The Roman walls of Pola have witnessed it all, from the dominium of Italians to that of the Austrians, Hungarians, French, and finally the Slavs. Its strategic position, opened to the sea and at the crossroads between western and eastern Europe, always made it a point of interest. As a result of the different invasions and occupations, but also by virtue of its own borderland nature, the population became a natural mixture of Italians, Germanics, and Slavs. And it was this mixed civilian population who most suffered the consequences of the conflicts that unfolded during the 20th century. Each time the political frontiers changed–with the moving of a line traced on a map–families, names, languages, and power moved along–leaving behind the pain of those excluded. The history of this land almost feels like a phantom story, half here and half there; it is the story of families and bonds that were lost, a story so painful that we refused to tell it for years. It was never an easy topic to discuss–even for my grandparents after decades of living in Italy, of being safe–and my parents, aunts, and uncles still ignore many of the details of our family’s migration. It seems that so does society as a whole. Still today, even though thousands of tourists from the boot vacation in Croatia every year, many Italians have never even heard of the Istrian exodus. And the same goes for all other local populations–from the Croats to the Slovenians, most suffering remains unknown and mostly unacknowledged even today.

During WWI and WWII, Istria was a land profoundly contested among Italy, Austria, and what was to become Yugoslavia, and when WWII ended in 1945, the region witnessed a power vacuum and political turmoil. Yugoslav Partisans, led by communist dictator Josip Broz Tito, took control of the area, a transition marked by violence and reprisals against those who were perceived as collaborators with the Italian Fascists or the Nazis. It became dangerous just to be Italian. These ethnic tensions and political vendettas culminated in the horrific Foibe massacres. Foibe, natural sinkholes found in the region, became sites where thousands of people, primarily Italians and some Croatians, were killed and their bodies disposed of. Some were even thrown in alive. Families were torn from each other, and around 300,000 Italians fled to the Italian mainland during the 40s and 50s. My grandmother was among them.

In 1945, she left the colorful town of Dignano, Istria, where she was born and raised, with her whole family. First, they made their way up to the northern part of the peninsula in hiding, sneaking between one impromptu home and the next, before finally deciding to leave the world that had always been their own. My family got on a boat and headed for the mainland. My uncle Nevio, who was then just a kid, recalls the fear, but also the lengths they went through to stay together, to raise each other’s spirits. Istria was annexed to Yugoslavia in 1954.

Others decided to stay, but in both cases, language became a powerful tool of discrimination. Italians from Istria who fled chose what looked like the most obvious option–what felt, in a way, more like home. A place they thought would be a safe harbor. This wasn’t always the case. In Italy, they were surrounded by people who spoke the same language they did–and yet, they were treated like strangers in their own country. Accents matter too, as they soon found out. They were called slurs, as my great-grand uncle Nevio recalls, pointed and stared at as if they came from some other planet. Families who had mixed with the Slavic populations carried proof in their surnames, and the prejudice they faced was even worse.

On the other side of the sea, back in Istria, language became the basis for violent cultural repression; as power often does, the new regime started with linguistics. Streets, towns, cities, lakes, mountains were deprived of their Italian names and given new Slavic ones. So it was that, overnight, Cittanova became Novigrad, Rovigno (originally from the Latin Rubinum) became Rovinj, Fiume became Rijeka, Capodistria Koper, Zara Zadar, and so on. For years after the war, it was common to see signs in public spaces, bars, and shops forbidding one to speak Italian. (Regimes are often mirrors of their opposites: years earlier, Fascists had done the same, forbidding Slavic languages to be spoken in public, and some claim, for example, that the Foibe massacres were a response to this Fascist oppression.) Language can be a tool for the marvelous creation of new invented worlds, or a tool of total destruction.

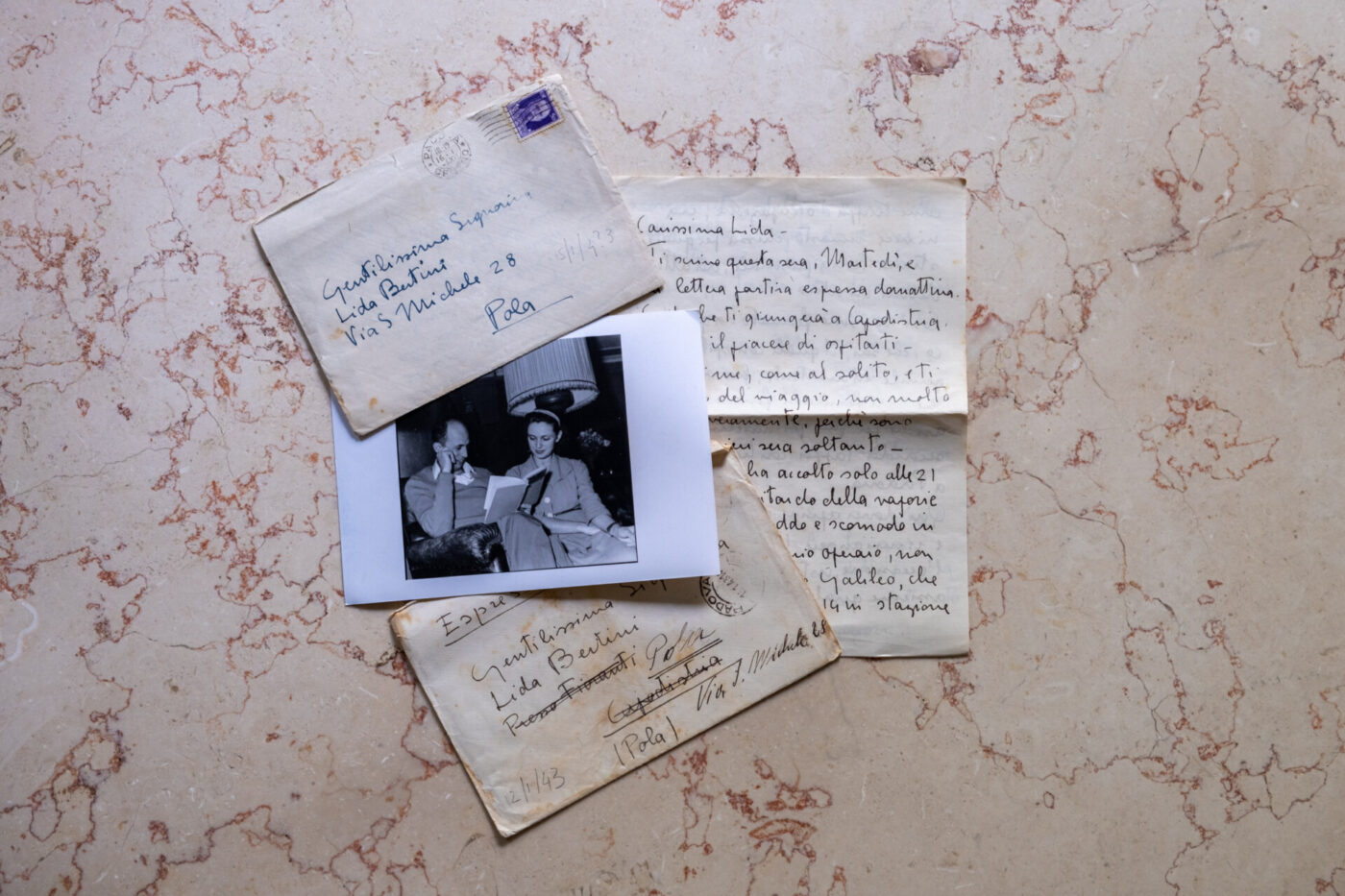

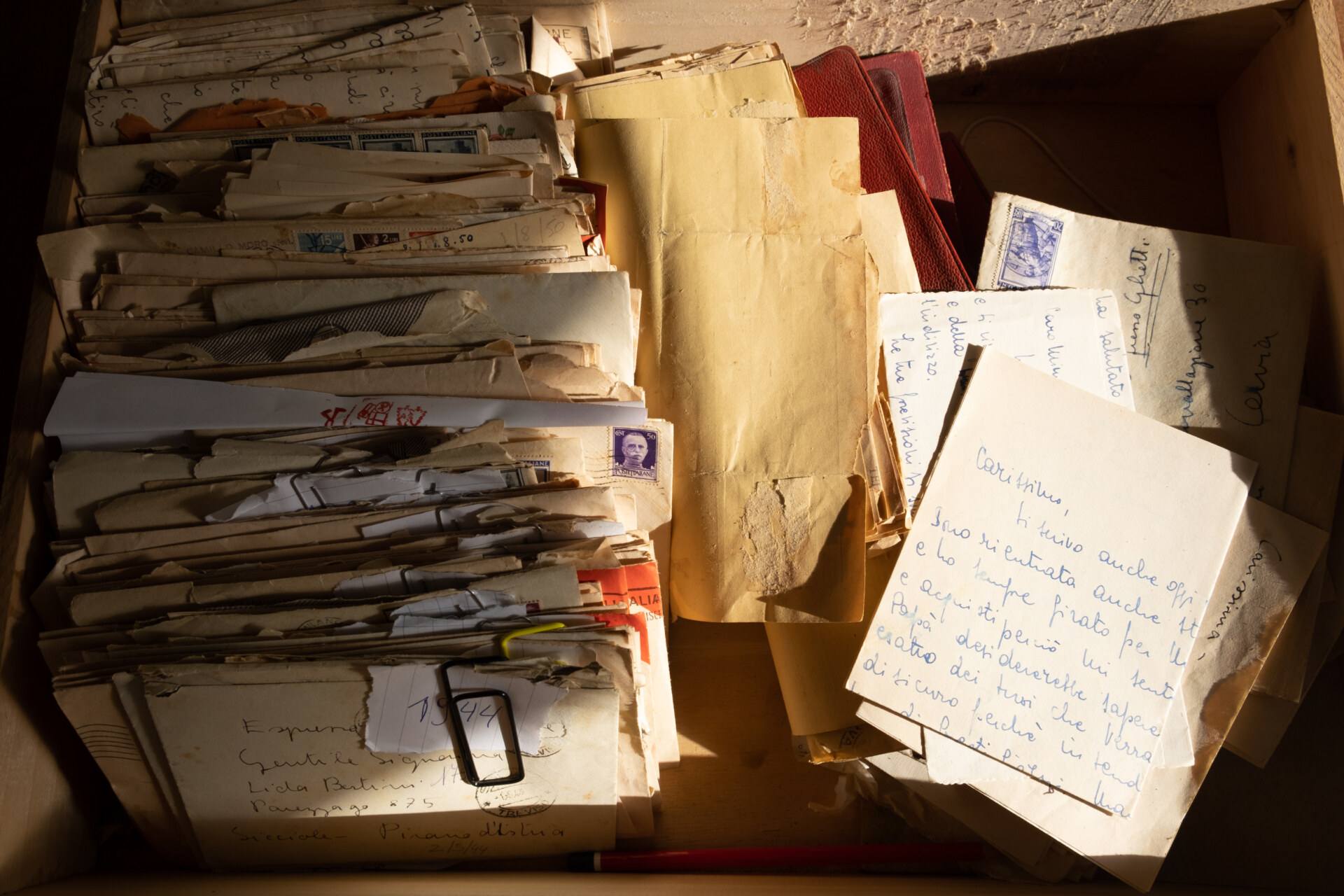

My grandparents’ words were traveling across the same land, the same sea, the same, vague borders at around the same time; their letters exchanged back and forth from Pola and Mommiano, Padova and Trieste, Buje and Dignano. He from the Italian mainland, she from Istria; they met in Pola when he was in the military and she was in high school, before she escaped. They spoke the same language, in an infinite number of ways as they found out, and fell in love. The words in their letters are words of fear, hope, trust, sadness, care, and love–universal emotions that transcend anything written. Their meanings are not lost, even at the hands of censorship, the marks of which, made by authorities, are still on the envelopes. “I understand the indecision and pain you feel at having to leave your native lands, and the special conditions increase the fear,” he wrote in 1944, “on the other hand, one must think that even a few days’ delay, given the instability, can cost a lot. I wish you in any case that the stars are always favorable to you.”

Those words ended up building a bridge. Between them and their worlds. Filling the gaps that war had created. After years, they ended up creating a family together, and taught their children the importance of choosing the right words–or so I’d like to think.

In the meantime, little by little and with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Istrian borders began to open up again and people started crossing them with increasing ease. The exchange began again, and the linguistic tear began to mend too. A co-existence was born. Those Italians who had decided to stay opened Italian schools to re-embrace their heritage. Serbo-Croatian is now commonly heard around the streets of Trieste. It’s common for people to live on one side of the border and work on the other. The result is a funny linguistic mixture, with most people freely interchanging between one language and the other. Words are occasionally coated with reciprocal resentment, but usually with a lot of mutual understanding. Irony and jokes fill the gaps. What matters is that each language found its place, and is abundantly spoken by almost all local communities. People have started opening up, sharing their similarities and differences. When I went back in July, I discovered that even village festivals are now simultaneously translated, with one host for each language, joking around their shared culturally tangled history.

I am, too, one of those Italians who travel to Istria–to vacation, but mainly to reconnect with part of my legacy. Going back to today, walking the same paved streets of the village where my grandmother was born, the same she must have walked on, I find myself humming that old song–“anche le pietre parlano Italiano”. And yet I believe that today the rocks of Istria speak a language that is not merely Italian. It is much more complex than that: their strata are layered, much like the history of this land. Theirs is also the language of war, of separation, but also, predominantly, of going back to the roots of it all, human beings simply exchanging words.