It was Autumn 2023, as the golden leaves began their descent to the ground and nature stripped itself bare for the winter, I found myself in Milan. A chill hung in the air, as did the impenetrable mists, which, as anyone who has visited northern Italy at that time of year will know, some days barely rose above the city’s highest spires, and I headed to the cinema to watch C’è ancora domani.

For days afterwards it had me musing on women’s rights, how lucky we are that things have changed, or so I thought. It was therefore with terrible poignancy that, only a few weeks later, I read about the murder of 22-year-old student Giulia Cecchettin by her boyfriend in Italy. Once again, Italian women’s rights and safety were thrust into public consciousness and, once again, the debate on violence against women was reignited. Thousands took to the streets in grief, shock, and anger, while flowers festooned railings in the small town of Vigonovo, near Venice, where Giulia’s family lived. Her family rallied for action and called for drastic changes on how women are treated and how boys are educated in schools in Italy, setting up the Giulia Foundation. Promises were made, campaigns were begun, politicians gave speeches denouncing the murder, international news reporters decamped to Padua and Veneto, and a foreign audience watched, appalled. It all seems rather promising–maybe something’s going to change!–until you learn that the rate of femicide in Italy has remained consistent over the past 60 years.

Cinema has long served as a mirror to society, reflecting its struggles, triumphs, and enduring injustices. In Italy, films have captured the reality of women’s rights—or lack thereof—for decades, offering a lens through which to examine the country’s cultural and social evolution. While the settings and eras may change, the themes remain unsettlingly familiar: women continue to face violence, often at the hands of those closest to them. Here, we take a closer look at the plight of women and the fight for their rights in Italy through films of the last 80 years.

Paola Cortellesi in C'è ancora domani

The 1940s – 1950s: Through the Lens of C’è ancora domani (There’s Still Tomorrow, 2023)

The post-war years were financially tough in Italy, as they were across much of Europe, but in 1945, spurred on by the newfound optimism and strength that came in the wake of Fascism’s fall, women gained the right to vote–though not without some backlash from their male counterparts. Italy, perhaps unsurprisingly, was one of the last European countries to give equal voting rights, followed only by Belgium (‘48), Greece (‘52), Switzerland (‘71), Portugal (‘74), and Liechtenstein (‘84). The first time Italian women could exercise their right was in 1946, voting on the monumental referendum that replaced Italy’s longstanding monarchy with a republic.

Though it came out 80 years later, Paola Cortellesi’s C’è ancora domani certainly captures the grim feeling of 1946 Rome. Post-war life is hard, American troops remain on the capital’s streets, but a sense of community remains strong, particularly among women. They watch each other’s children playing, do their families’ laundry together, catch up on the neighborhood’s latest snippets of gossip; but their support for one another did little to help behind closed doors. Another stark reminder that these traditionally domestic, “female” spheres remained under male control.

Such is the unfortunate case for protagonist Delia, played by director Paola Cortellesi, whose husband physically assaults her and whose father-in-law verbally assaults her daily. Though her screams can be heard by her neighbors and friends, they seem powerless to do anything. It’s truly painful to watch, especially when Delia’s daughter, Marcella (played by Romana Maggiora Vergano), starts to fall into the same patterns with her boyfriend–the director’s hint to the cycles of abuse. The film concludes (spoiler alert!) with Marcella helping her mother to leave her abusive home, a pivotal moment that coincides with and is inspired by her mother’s decision to vote for the first time. This small act of defiance against the men in her life (and the overall patriarchal system) gives Delia a chance to confidently restart, as she’s able to finally act both for her own future and also that of her country.

The gender inequality and domestic violence explored in the film are certainly not limited to 1940s Italy. Statistics for the rates of domestic violence and femicides of that time are difficult to come by, likely because, as we can see in the movie, abuses mostly happened behind closed doors; reporting the aggressions against women certainly didn’t get much media spotlight. While Italy’s femicide rate is actually low when compared to the rest of Europe, it has remained consistent over the past 60 years, while male homicides are steadily decreasing. The number of women killed by people close to them also remains shockingly high. In 2023, at least 117 women were murdered; more than 75% at the hands of a current or ex-partner.

A 2015 ISTAT report states that “13.6% of Italian women have suffered physical/sexual violence from a current or ex-partner”, while “24.7% of Italian women have suffered physical/sexual violence from non-partner men”; though the gap between the numbers seems wide, the same report states that “the most serious forms of violence are perpetrated by partners, relatives, or friends.” When it comes to overall gender equality, as of 2024, Italy stands on the scale at 69.2, which is below the EU average of 71. Out of the 27 European countries, Italy ranks 14th for equality. Both in and out of the workplace, women are still at a disadvantage, whether in 1946 or 2024. And while shocking, these numbers do little to reflect the daily aggressions that women like Delia have and will continue to face.

Anita Ekberg at Cafe De Paris

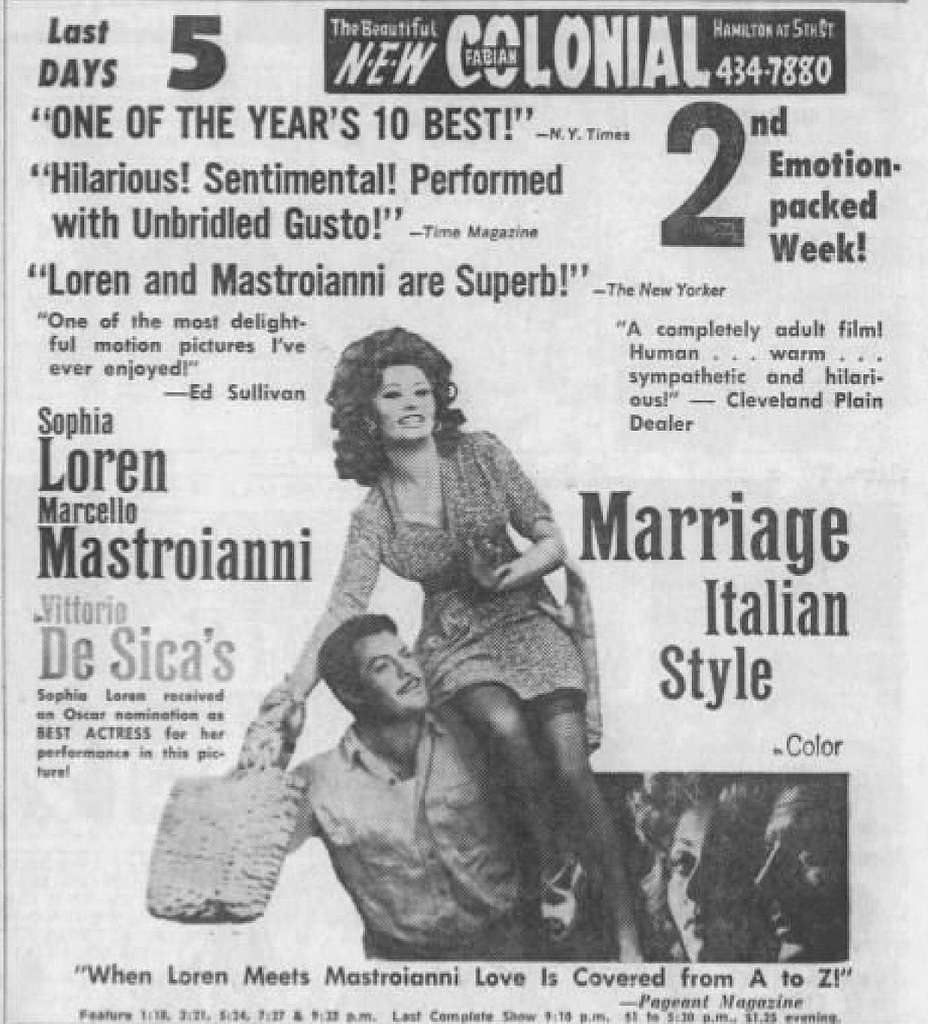

The 1960s: Through the Lens of La Dolce Vita (The Sweet Life, 1960), Divorzio all’italiana (Divorce Italian Style, 1961) & Matrimonio all’italiana (Marriage Italian Style, 1964)

In the 1960s, Italy’s economy was booming thanks to the onset of industry, with car and household appliance production replacing agriculture. In this decade, women in Italy started attending secondary school for the first time–which meant they had a chance to pursue careers, gain their own financial independence, and have alternatives to being homemakers and mothers.

The decade also brought the golden age of Italian cinema, and Federico Fellini, Sofia Loren, and Marcello Mastroianni became household names. But, the glitz and glamor of the “Dolce Vita Era” wasn’t so glamorous for women, and certainly didn’t reflect their newfound freedom. In films and TV, a few painful female stereotypes were played on again and again, depicting the female protagonists as sexualized objects, dutiful housewives, or hysterical and overly passionate individuals–and sometimes, as all three.

One of Fellini’s most famous films, La Dolce Vita explores themes of hedonism, existentialism, and the emptiness of modern life. The story focuses on tabloid journalist Marcello, played by icon Marcello Mastroianni, who sets out to discover the “dolce vita” of Rome. He drifts through decadent parties, shallow relationships, and fleeting moments of beauty–namely prostitutes, actresses, waitresses, any beautiful woman he passes on the street, including the famed Anita Ekburg. The only woman he doesn’t seem to be tempted by is his own wife, who is desperately struggling with her mental health. Here, we have the two female caricatures: a hysterical lady, and the overly sexualized beauty, created to fit the desires of the male audience at the time. The latter is what we now know of as the Italian femme fatale stereotype: sexy, spontaneous, elusive, equal parts desirable and dangerous, waiting to lure you into the forbidden waters of the Trevi Fountain while your wife lies sick at home.

While La Dolce Vita depicts women as sex symbols, tempting Marcello away from his work and his marriage, Divorzio all’italiana turns to the stereotype of housewives. In the dark comedy, Rosalia (Daniella Roca) and Ferdinando (Marcello Mastroianni) are an unhappily married couple, living with Ferdinando’s also unhappily married parents. Fed up with his “nagging” wife, Ferdinando falls head over heels in love (in truly exaggerated Italian comedy fashion) with his young cousin Angela, deciding he wants to marry her and leave his wife. The only snag? Divorce was illegal at the time. Ferdinando decides on the next plausible course of action: to kill his wife. He plans to frame her and “catch” her cheating, providing the perfect excuse that he was “preserving his honor”. Horrifying. Ferdinando’s idea unfortunately comes from the basis of a popular trend at the time: “honor killings”, one of the few “acceptable” ways out of a marriage–resulting in a criminal sentence shorter than a “non-honory” killing and that of divorce.

Designed to be a social commentary of the time, the issues in the film are certainly exaggerated, but not fabricated. Prior to 1981, murders of “spouses, daughters, and sisters caught in illicit sex” were treated with a degree of leniency, as they were seen as “defending the honor” of the family or man; only men who could get away with pleading for “honor” after murder. No wonder Italy’s rates of femicide were so high, since it was only in 2007 (you read that right) that “honor killings” were declared to be an “obsolete” concept by the Italian courts.

Restrictive laws around divorce kept couples in unhappy, even abusive relationships. Perhaps it was a hangover from the years of Fascism in Italy and its traditionalist views, or perhaps it was the Catholic Church, which vocally opposed the legalization of divorce both before and after its legalization in 1970. But, with this new law, women had a newfound freedom to exit unhappy or abusive marriages on their own terms–death not included. Whether they were given the tools to do so, and what society’s views on their actions would be, remains a whole other story.

Vittorio De Sica’s Matrimonio all’italiana has a similarly sinister comedic tone. Male lead of this decade, Marcello Mastroianni, again, acts as businessman (or some might say womanizer) Domenico, and his fiery counterpart Filumina, played by Sophia Loren, is a much younger girl from the countryside. Domenico meets Filumina at a brothel, and the two have an on-and-off-again relationship over the course of some 20 years. Filumina appears to be deeply in love with Domenico, who continues to string her along although he doesn’t feel the same. At one point in the film, hearing that Domenico might be engaged to someone else, Filumina pretends to be seriously ill, convincing Domenico to marry her while she’s on her “deathbed”–when he agrees, she almost instantly recovers. And Domenico, realizing that he’s been tricked, is furious.

While the relationship that plays out over the rest of the movie is entertaining and funny, Filumina is portrayed as over-emotional, violently jealous, deceptive, and demanding, just waiting to “trap” men into institutions like marriage. The love that Marcello’s character in Divorzio all’italiana has for the young woman is passionate and comedic (yes, we’re talking love he’s willing to kill his wife for), but audiences are supposed to believe that Filumina is the true mad one, rather than Marcello. Maybe, Filumina isn’t “emotional” and “crazy”, but full of tact and business acumen. Back in the 1960s, securing a marriage to a wealthy man of good social standing would have guaranteed financial support for her and her three children (whom Domenico had yet to learn about). In this sense, one could argue that Filumina’s actions are quite rational. It’s likely one of the reasons why, the year the movie came out, the crude marriage rate (the ratio of the number of marriages during the year to the average population in that year) was 8.1%. Compare that to 3.2% in 2022.

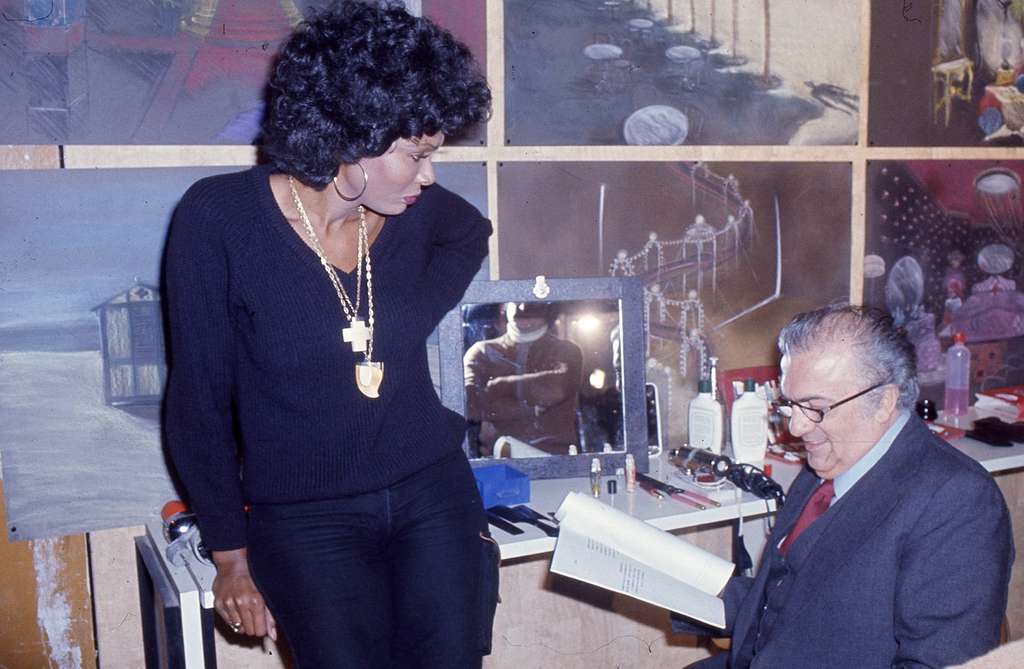

Ajita Wilson auditioning with Fellini for La Citta delle Donne

The 1970s – 1980s: Through the Lens of La Citta delle Donne (The City of Women, 1980)

In the 70s, a wave of feminism spread across the Atlantic Ocean from the United States, and soon took hold in Italy. A whole host of legal changes came with this movement, following the legalization of divorce at the turn of the decade: these included legalizing birth control pills (1971), giving women and men equal legal rights in marriage (basically abolishing the legal dominance of a man in the marriage, 1975), criminalizing marital rape (1976), granting women equality at work (1977), and legalizing abortion (1978). Women were, finally, less reliant on their male counterparts. But for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction, and as feminism gained greater influence in Italy, opposition from the other side of the political spectrum intensified. In response, critics sought to discredit feminist women, labeling them as “militant” and “man-hating” in an attempt to undermine their movement.

In one of his most controversial films, La Citta delle Donne, Fellini reverses gender stereotypes. Women take control and dominate the world that Snàporaz (played yet again by Marcello Mastroiani) stumbles into. They objectify Snàporaz, try to assault him, treat him with disrespect, lie to and cheat on him. This all-female ensemble is enough to send Snàporaz scurrying away.

It’s no wonder that the reviews were so mixed–one critic from the The Philadelphia Inquirer distilled it down to “a 138-minute collage of dreams and sexual fantasies” while another from the Chicago Sun-Times wrote that the film “pretends to be about feminism, [although] it reveals no great understanding of the subject; Fellini appeared to see feminists as a threat.” Elsewhere, the public seemed to interpret the film in similarly disjointed ways, with some praising the critique on men’s behavior and dominance and others condemning the radical feminists. Perhaps women with their newfound freedoms and beliefs were becoming too much for Italian society. Whatever Fellini’s intention, for one thing, it did get people talking.

Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni in Matrimonio All'Italiana

Since the 1980s, women in Italy have gained increasing rights and protections. In 2013, gender-based violence was finally recognized in court, and in 2001, a law was passed prohibiting the firing of pregnant women. Domestic abuse laws continue to evolve, including a recent amendment to the codice rosso law, which strengthens protections for those reporting domestic and gender-based violence.

Cinema, too, has seen progress. Women are gaining more diverse and less stereotypical roles, both in front of and behind the camera. Notably, C’è ancora domani—the only film on this list directed by a woman—marks a step forward in representation.

One can only hope that the next 77 years will bring even greater advancements for women in Italy and beyond. I’m looking forward to seeing it on the silver screen.