We’ve all been there. Set off with grand plans of visiting at least two museums a day, over a three-day trip, to get the full-on cultural kick. Then other things inevitably get in the way. How long does the visit take? The line is how long? Tickets cost that much? Suddenly a museum checklist seems less like fun and more like being on a school trip.

Rome is among those cities where the battle between getting your culture fix and ticking off your shortlist of restaurants and bars is an intense one. Some of Italy’s (and indeed the world’s) finest art and archaeology is distributed across the sprawling city; Rome wasn’t built in a day, and you certainly need more than a few to take in all of the museums. (Just to do the Vatican justice, you need at least three hours, and that alone is enough to leave you culturally saturated for the day.)

Thankfully, though, Rome is a place where some of its most important works—by the likes of Caravaggio, Michelangelo, and Bernini—still remain in the settings for which they were originally created—that is, churches and palaces.

The latter takes a bit more effort—either an entry fee or a friendship with the aristocrats still living there—but churches, free and easy to pop into, are another story entirely. Rome has over 930 of them, and while not every one holds a masterpiece, more than a few are well worth a detour.

Though, more often than not, you won’t have to detour: these churches, outside of tourist hotspots, are conveniently located near cafés worth visiting for a morning espresso, top spots for aperitivo, or great restaurants for lunch or dinner. (An added bonus: many Roman churches stay open late, making the perfect prelude to an evening meal.)

Here, 11 Roman churches you can easily work into a “cultural” day in the Eternal City—no queuing required.

Chiesa di San Luigi dei Francesi

Caravaggio’s characterful life and characteristic chiaroscuro need little introduction, nor does the role that Rome played in his life. There are 26 artworks by Caravaggio located across the city, and most striking are those that remain in the churches Caravaggio designed them for.

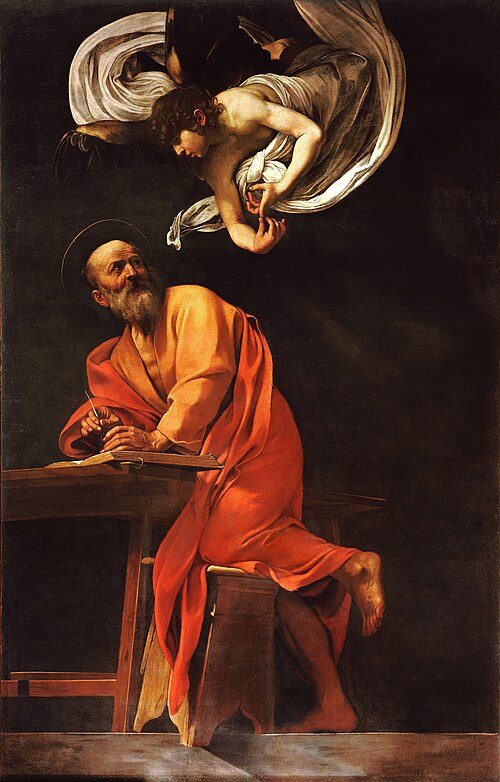

Caravaggio was a master of light and shade, and he used the darkness of church settings to his advantage. In the Contarelli Chapel, Caravaggio was commissioned for three paintings on the life of Saint Matthew. The painting on the left wall, the Calling of Saint Matthew, is a perfect demonstration of how Caravaggio designed the painting for the space itself, with the light that streams through the window in the painting aligning with that of the chapel. The same could be said for the Martyrdom of Saint Matthew on the right wall, where the contorted bodies are thrown into sharp relief and appear almost as if emerging from the painting itself. In the central painting, The Inspiration of Saint Matthew, the saint is shown at his desk, turning in surprise as an angel appears to deliver his heavenly message. Clad in a rich orange robe and a torn white sheet, respectively, Matthew and the angel are the painting’s only sources of light—set in stark contrast against the surrounding gloom. As Caravaggio increasingly experimented with spatial dynamics, this composition’s relationship to the chapel and altar remains especially compelling.

Inside Chiesa di San Luigi dei Francesi; NikonZ7II, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Basilica di Sant’Agostino

Just steps from San Luigi dei Francesi, this church—and the artwork inside—often goes unnoticed. In the Cavalletti Chapel hangs Caravaggio’s Madonna dei Pellegrini (Pilgrim’s Madonna), in which two peasants kneel before a Madonna who radiates the elegance of a silver screen siren. There’s an immediacy, an intimacy, in the way she casually leans against a colonnade, and in the dirt-caked feet of the pilgrims, placed squarely in the viewer’s gaze. It’s another striking example of Caravaggio’s gift for bringing the divine down to earth.

Also don’t miss Raphael’s fresco of the Prophet Isaiah. It may not be his finest work, but it offers a clear glimpse into his painterly evolution after arriving in Rome. Painted circa 1512, it shows the unmistakable influence of Michelangelo’s recently completed Sistine Chapel—especially his own Isaiah—in both the pose and the heaviness of the figure.

Caravaggio’s Madonna dei Pellegrini

Basilica di Santa Maria del Popolo

Piazza del Popolo has always held, for me, a slight air of isolation—its position at the far end of Via del Corso marking the outer edge of the city center. Just inside the Porta del Popolo, however, sits the church of the same name, a must-visit for its Caravaggio paintings. In the Cerasi Chapel, the artist was commissioned to create two works flanking Annibale Carracci’s central altarpiece, The Assumption of the Virgin, in what was meant to be an artistic confronto—a face-off between two of the greatest artists in Rome at the time.

Here, Caravaggio took full advantage of the chapel’s tight quarters, playing with perspective to heighten the drama of each scene. In The Conversion of Saint Paul, the fallen general is dramatically foreshortened, his body lit by a shaft of divine light. A similar intensity pulses through The Crucifixion of Saint Peter, in which the saint turns his head toward the viewer as his body is hoisted onto the cross.

Not to be overlooked is the mosaic designed by Raphael in the Chigi Chapel. Completed in 1516, it crowns the dome with The Creation of God at its center, surrounded by astrological figures in their ancient Roman forms. A personal favorite: Venus with Cupid, joined by the symbols of Taurus and Libra.

Basilica di Santa Maria del Popolo in Piazza del Popolo

Chiesa di Santa Maria della Pace

It’s difficult to say what della Pace brings to mind more immediately: this gem of a church or the historic caffè of the same name, a bastion of Rome’s coffee culture. At the former, the semi-circular portico that marks the façade hints at the imposing structure of the Cloister of Bramante inside. The cloister exemplifies how Renaissance ideals sought to merge Classical forms with Ionic and Corinthian columns, creating a sense of balanced harmony. It may appear stark at first glance, but pause for a moment and you’ll realize the space is designed to defy gravity.

The church interior also holds several noteworthy frescoes, set above two chapels in the nave. In the Chigi Chapel, look for Raphael’s Sybils and the Angel—another clear nod to Michelangelo’s influence and his Sistine Chapel designs. In the neighboring chapel, don’t miss the work of Rosso Fiorentino. Though less famous than Raphael, Fiorentino was a key figure in the Mannerist movement that emerged after the Sack of Rome in 1527. His style is marked by expressive gestures and (deliberately) exaggerated forms, evident in the striking scenes of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

The semi-circular portico that marks the façade; Donato Bramante, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Raphael’s Sybils and the Angel frescoes; Sailko, CC BY 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Basilica di Santa Maria Sopra Minerva

As the name hints, this church was built sopra—or on top of—the ruins of a Roman temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva. The interior is Gothic in form, with a central nave painted in brilliant ultramarine frescoes that imitate a night sky, dotted with apostles and angelic figures. Be sure to stop by the Carafa Chapel, where the Florentine artist Filippino Lippi’s frescoes masterfully merge religious figures with depictions of his contemporaries. Also tucked within the church is one of Michelangelo’s lesser-known sculptures, Christ Carrying the Cross. The powerful, nude figure of Christ stands in the balanced pose known as contrapposto, gripping the cross; the bronze loincloth was a later, modest addition.

Also don’t miss the Egyptian obelisk in the piazza outside, balanced atop an elephant sculpture by Bernini. The surprising design was inspired by a print that appears in the renowned 15th-century book Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (Dream of Poliphilo).

The ceiling at Basilica di Santa Maria Sopra Minerva; Courtesy of Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0

Chiesa di Santa Maria della Vittoria

There is one reason for visiting this church, and that is Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. No jostling crowds to contend with, as with the Bernini sculptures on display at the Galleria Borghese—instead, you can fully appreciate his skill in carving life from marble. Is Teresa in religious ecstasy, or in the throes of something else? No comment on my opinion here… all I’ll say is that Bernini was no stranger to a woman’s flesh.

In the darkened church setting, the nun’s skin appears almost translucent as she raises her head towards the heavens, while the golden rays that frame her and the angel who pierces her heart lend a gentle glow. To create the effect of heavenly light, Bernini devised a hidden window in the dome of the aedicule, allowing sunlight to stream in and truly flood the scene with light from above. A stroke of theatrical genius—and utterly mesmerizing.

Basilica di Santa Maria in Trastevere

Founded in the 3rd century, this basilica is a Medieval outlier among the sea of Renaissance and Baroque churches that fill the city. And that means gold—lots of it. The façade is adorned with a golden mosaic frieze, setting the tone for the main event: the apse’s dazzling 12th-century mosaic of the Enthroned Virgin Mary and Christ, flanked by saints and key figures of the Church. Additional scenes from the Life of the Virgin were added in the 13th century. (Note the very-Byzantine touch of the Pope who commissioned the remodel, holding a miniature version of the church itself.)

Plus, the columns lining the nave were repurposed from the ruins of the Baths of Caracalla—a prime example of the Roman tradition of architectural “recycling.”

Basilica di Santa Maria in Trastevere façade; Photo by Slices of Light via Flickr

Basilica di Santa Sabina

Rome has seven hills, and of these, I’d argue the Aventine is the one to seek out when you need a break from the city’s full-blown sensorial onslaught. From its elevated vantage point, it offers unrivaled views over the Tiber toward the Vatican, while the surrounding parks (giardini) only deepen the sense of calm. Set beside the Giardino degli Aranci, the Basilica di Santa Sabina easily ranks among the prettiest church settings in all of Rome.

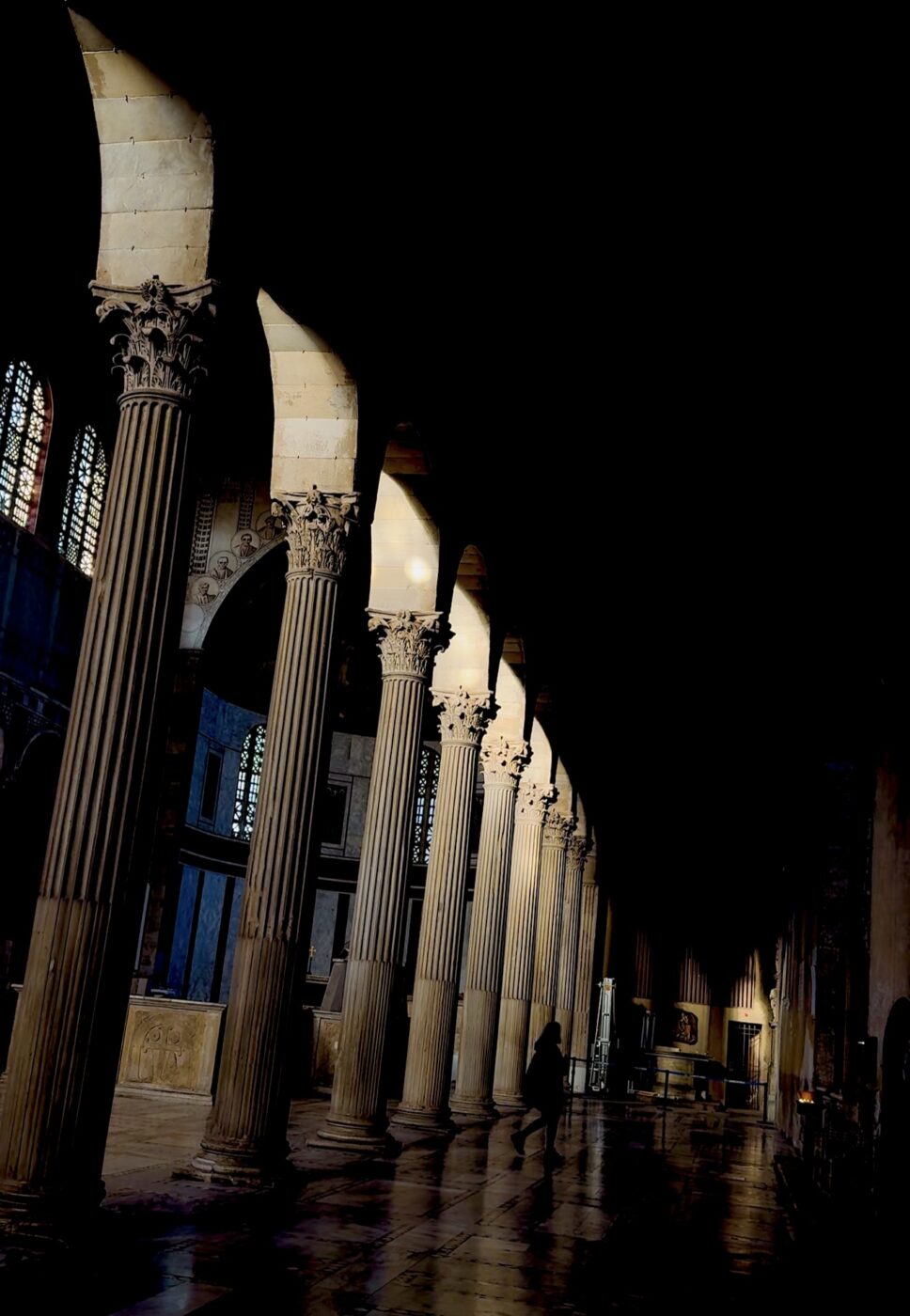

The church itself is an imposing example of early Christian architecture, built in the 5th century when the basilica layout—an elongated nave ending in an apse—was adapted from Roman civic buildings. Santa Sabina is dedicated to the eponymous saint, martyred for converting to Christianity, and stands on the site of an ancient imperial residence. The solemn interior is marked by its soaring ceilings and three naves, divided by two rows of Corinthian columns repurposed from the Temple of Juno. Don’t miss the colossal wooden doors, carved with Biblical scenes and likely dating to the church’s original construction.

Basilica di Santa Sabina

Chiesa di San Francesco a Ripa

Another church for those on the trail of Bernini’s sculptures—and another woman caught in a pose that blurs the line between spirituality and ecstasy. Here, Bernini created a funerary monument for the Blessed Ludovica Albertoni, capturing the moment of her mystical communion with God. She reclines on a bed, her body arched, hands clasped to her chest. One of the last sculptures Bernini completed, it’s a masterclass in his skill for turning movement into stone—especially in the rippling folds of fabric, carved with astonishing delicacy.

The metaphysical painter Giorgio de Chirico is also buried here, for those keeping an eye out for modern ghosts.

Bernini's funerary monument for Ludovica Albertoni; Sailko, CC BY 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Chiesa di San Pietro in Montorio

Perched just above Trastevere, with a view over Rome’s rooftops, this church is well worth the short walk. Once home to Raphael’s final painting, The Transfiguration (now in the Vatican), it also houses two works by Sebastiano del Piombo—The Flagellation and The Transfiguration—painted from drawings provided by Michelangelo, in a fascinating example of their long creative collaboration.

But the real gem is in the church’s courtyard: Bramante’s Tempietto. Built in the early 1500s, it shows how ancient Roman temples inspired the balanced, harmonious ideals of High Renaissance architecture. Its centralized plan draws on classical forms—like those at Tivoli—reimagined through a blend of styles, like Tuscan colonnades paired with a classicizing entablature. I’ll stop before this gets too architectural, but suffice to say: this is a true jewel in the crown of Rome’s churches. Best of all? Time it right, and you might have it all to yourself.

Bramante's Tempietto in the courtyard of Chiesa di San Pietro in Montorio; Di Herbert Weber, Hildesheim - Opera propria, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68138674

Basilica di San Clemente al Laterano

There’s only one way to end this shortlist, and that’s with a church, just beyond the Colosseum, that reveals the layered complexities of Rome’s history.

The current (11th-century) basilica is worth a visit on its own for its intricate mosaics, which can be seen without a ticket—and as it remains little visited, you’re unlikely to encounter a line. But to reach the part that truly gets to the heart of things, you’ll need to descend—and you do need a ticket.

Below is a 5th-century basilica: simpler in form, but echoing the structure above. And further down still, at the lowest level, you’ll find what makes this site unforgettable—a 1st-century temple dedicated to the cult of Mithras—essentially, Christianity’s early competitor. The Mithraeum is a small, shadowy chamber with an altar dedicated to Mithras sacrificing a bull.

Here you’ll understand Rome’s dialogue between its Pagan past and Roman Catholic present. This, I’d argue, is the ultimate primer for how the Roman Catholic churches “above ground” truly came to be.

Just wait until you get below ground at Basilica di San Clemente al Laterano; Dudva, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons