It is in one of Filippo Marinetti’s early Futurist manifestos that, “sitting on a tank of petrol” within the whirring innards of an airplane, he describes himself soaring over “the mighty smokestacks of Milan.” There, high above the billowing, churning proof of Italian progress, the airplane propeller “speaks” to him: it tells him how literature may be brought away from the archaism of tradition and into the future.

Marinetti’s surge of inspiration upon his aerial viewing of the city speaks to the inextricable connection between Milan and Futurism, for it was in the very streets of the city that the artistic and social movement began.

A Near Miss and the Birth of Futurism

In October of 1908, the Milanese poet, Marinetti, was driving his new Fiat sports car down Milan’s Via Domodossola, when an incoming cyclist caused him to swerve into a ditch. The crash, albeit life-threatening, provided the young poet with a revelation. He saw it as a symbol of how the old (the bicycle) needed to give way to the new (the car) in order for society to be able to progress. The following year, he launched the Futurist movement in the form of a manifesto, its founding principle being the rejection of antiquity and a wholehearted embracing of modernity. He and a group of likeminded creatives dismissed Italy’s obsession with the classics, academia, and museums as a dangerous and redundant fixation on the past. Instead, the Futurists said, literature and art had to break free of tradition, and channel the dynamism of a modern and increasingly industrial Italy. It was only in tapping into the zeitgeist of an age of major technological advancement that the arts could truly serve their purpose.

And what better city for such a movement to take place than Milan? One corner of the so-called “industrial triangle” formed by the cities of Milan, Turin, and Genova, the city played a major role in Italy’s economic development at the turn of the century. Home to the first power station in continental Europe, booming steel and textile sectors, and the most advanced railway network in northern Italy, Milan was an industrial and financial capital and, as such, represented the seductive potential of a “modern Italy.”

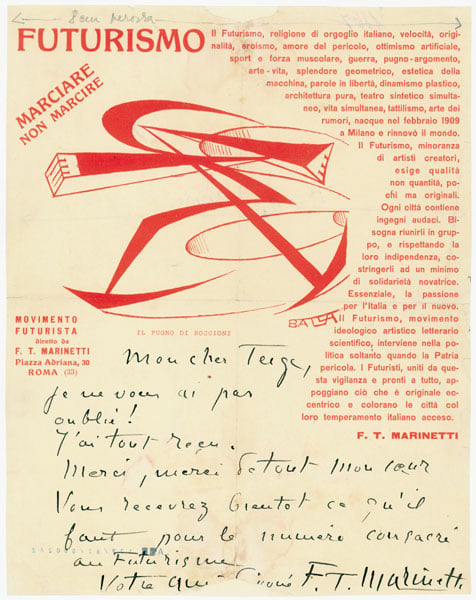

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

Cityscapes and Serate Futuriste

The city was the perfect spot, then, for Marinetti to curate his tight-knit group of artists and intellectuals; against the kaleidoscopic backdrop of urban Milan, the Futurists would meet, discuss, drink, and create. What Paris was to the Surrealists, Milan, “la città futurista”, became to the Futurists. At Marinetti’s own home on Corso Venezia, known as “la Ca’ Rossa” for the red hue of its façade, serate futuriste (futurist evenings) became a frequent affair. In and out of its four walls flitted writers, musicians, artists, and dancers; moths to the glow of Marinetti’s influence. Russian composer Igor Stravinsky wrote of his own attendance over the course of three evenings that Marinetti was “a tireless talker-but also the kindest of men”, and his serate took place in “the oriental salon of the Egyptian vate”, where, amid “trinkets”, and “big electric insects” attached to the wall, thronged everyone from Futurist artist Carlo Carrà to Duke Visconti di Modrone, director of La Scala. Amongst Milan’s artistic and intellectual elite, culture and politics were hotly discussed, and the serate soon spread beyond the realms of Marinetti’s “oriental salon” and out onto the stage, where they were used as a propaganda campaign for the Futurist movement across the country.

In a bid to disrupt the typically static and bourgeois space of the theater, Futurists would recite provocative poetry, spout political rhetoric, and hurl insults at the audience. One cartoon by Futurist artist Umberto Boccioni shows audience members gesticulating furiously, throwing rotten vegetables at the Futurists onstage, while another presents the Futurists as composers, directing the “orchestra” of the audience to sound different instruments. These serate were intended to disrupt, and the wild debates were known to erupt in fights that often culminated in dismantlement by the authorities, with Marinetti himself arrested more than once.

Beyond the insects and trinkets of Marinetti’s salon, or the bright lights of the stage, Milan’s urban cityscape was the ultimate source of Futurist inspiration. Here, modernity ruled, with the proliferation of factories, railways, and tramlines birthing a technological hub that was alien to Italy’s other historic cities; a fact stressed by Marinetti and a handful of his Futurist peers in a public denouncement of Venice, Rome, and Florence for their rejection of modern industry.

Piazza Cordusio in the 1930s

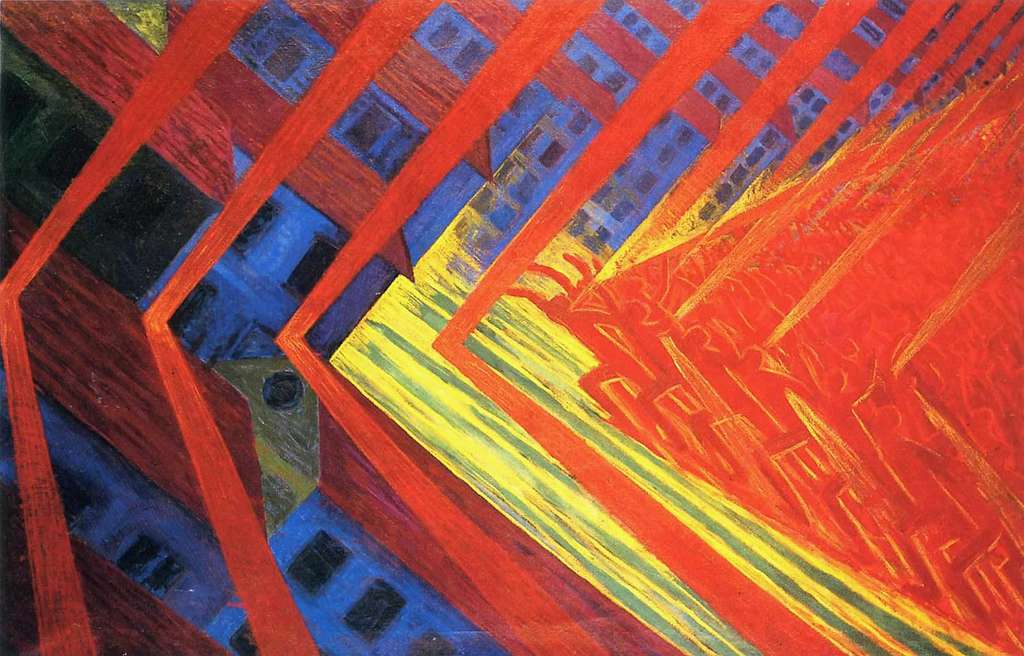

Marinetti firmly situates “The Futurist Manifesto” within such an urban landscape: in its introduction, he describes he and his friends as distracted “by the rumbling of huge double decker trams that went leaping by, streaked with light like the villages celebrating their festivals, which the Po in flood suddenly knocks down and uproots…” The buzz of Milan’s sights and sounds is complete with “hungry automobiles… snorting machines”; a sign, Marinetti exclaims, that “mythology and the mystic cult of the ideal have been left behind.” Luigi Russolo’s 1913 famed painting “Dynamism of a Car” reiterates the significance of urban machinery in the Futurist imagination. Here, hot scarlet and steel gray geometric shapes form arrows that encourage the viewer to look off frame–perhaps towards the future. The work conjures up an automobile in the abstract, its fragments creating the impression that the machine is bending temporal and spatial boundaries, able to occupy multiple positions at the same time through its newfound speed. The combination of color and shapes recall the flame and metal of mechanical industry, and situate the automobile as a flagship symbol of urban development.

Luigi Russolo's "La Rivolta" (1911)

Depero and “Fatally Modern” Advertising

The evolution of public transport and the automobile did significantly change the cityscape, giving Milan a whirring, clanging heartbeat to which the Futurists marched. But there was more change to come. Amidst the city’s smoking machinery appeared advertisements; posters and luminous signs roared their way down Milan’s busy streets. Adverts, quick, commercial, and new, were quintessentially Futurist, and wholeheartedly embraced by Marinetti and his peers.

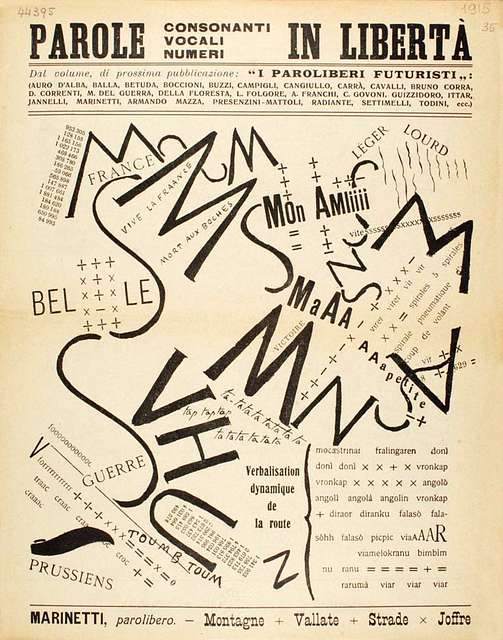

Futurist artist Fortunato Depero described it as “a decidedly colorful art”, that “boldly placed itself on the walls, on the façades of buildings, in shop windows, on trains, on street floors, everywhere…”, writing that “even an attempt was made to project it onto the clouds.” Depero himself was central to the revolution of Italian advertisement, moving it away from the 19th-century style and towards a fiercely eye-catching form of graphic design. In his decade-long collaboration with Campari, Depero’s designs were characterized by bold colors, geometric shapes, and experimentation with typographical form typical of the Futurist parolibere, in which the textual was merged with the pictorial. Advertisement was the perfect medium for the Futurists to experiment with simultaneity, and they employed graphic design to evoke an instant multi-sensory experience of the brand product.

This was an art that, to Depero, was “fatally necessary and fatally modern”, and the bold design of Futurist adverts quickly became a staple feature across Milan’s streets and squares, smothering old buildings with colorful bursts of contemporary commercial reality. Aldo Palazzeschi, a Futurist poet, wrote of the changing cityscape in his poem “La Passeggiata”, a written observation of all the advertisement inscriptions he could see on a walk along Milan’s Corso Garibaldi. Marinetti, too, made his support clear for Milan’s jostling advertisements, writing an open letter to Mussolini in 1927 to counter a proposal for turning off the illuminated advertisements in the Piazza del Duomo. In their defense, he wrote that the adverts were a symbol of progress, representing the “defeat of the hated 19th century” as the romantic moon so revered in poetic tradition was replaced with these “electric moons” that lit up the face of the Palazzo Carminati.

A Depero-designed poster for Futurist theater

The Fall of Futurism (and Fascism)

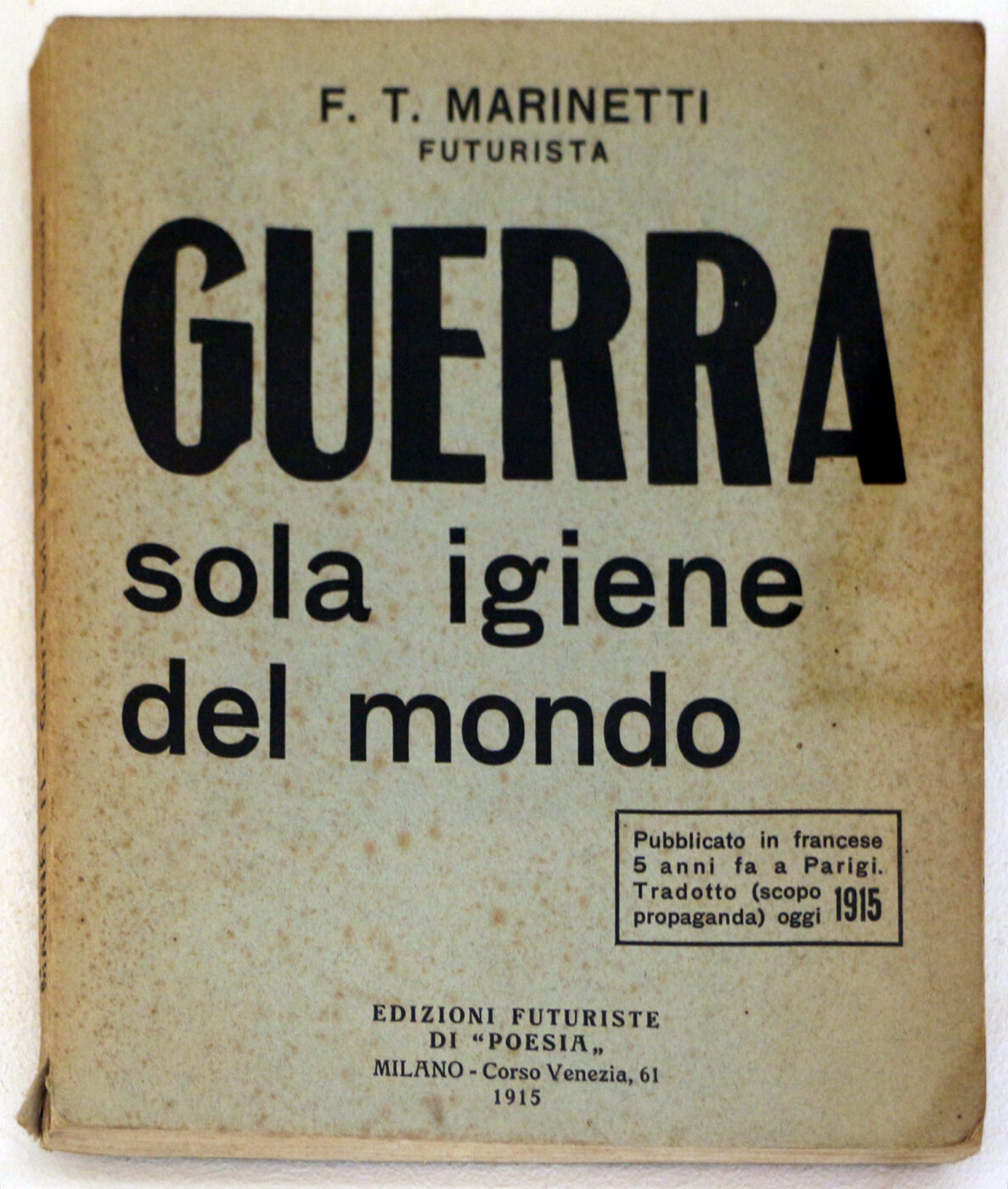

The Futurist movement dissolved for good along with Marinetti’s death in 1944. The movement had been closely linked to Fascism due to ideological similarities (ardent nationalism and glorification of violence, among others), as well as widespread Futurist support of the Fascist party. Their already declining popularity soured completely with the end of WWII, as Futurism became associated with the disgraced political regime. Marinetti’s long-standing connection to the city was made final, his body buried in Milan’s Cimitero Monumentale.

Traces of the movement, however, can still be found in Milan, memories of la città futurista. The second floor of Milan’s Museo del Novecento, known as the Galleria del Futurismo, houses one of the largest collections of Futurist work in the world. Likewise, the old Futurist haunt Casa Boschi di Stefano on Via Giorgio Jan, frequented by artists and intellectuals alike, is now home to an impressive collection of 20th century Italian masterpieces. Marinetti’s home, the infamous Ca’ Rossa, may be long gone, but it is worth heading to Corso Venezia anyway to blink in the artistry that once was, and read the inscription on the commemorative plaque:

Da qui il Movimento Futurista lanciò la sua sfida al chiaro di luna specchiato sul naviglio. (From here the Futurist Movement launched its challenge to the moonlight mirrored on the Naviglio.)

The plaque sends a resounding message: no more romantic talk of moonlight on water, the Futurists call out long after their demise; especially not on the water of the navigli, Milan’s interconnected canals that date back to the Middle Ages. Instead, let us talk of movement, speed, noise, and commotion, the bright lights of the city, and always, always, the future.

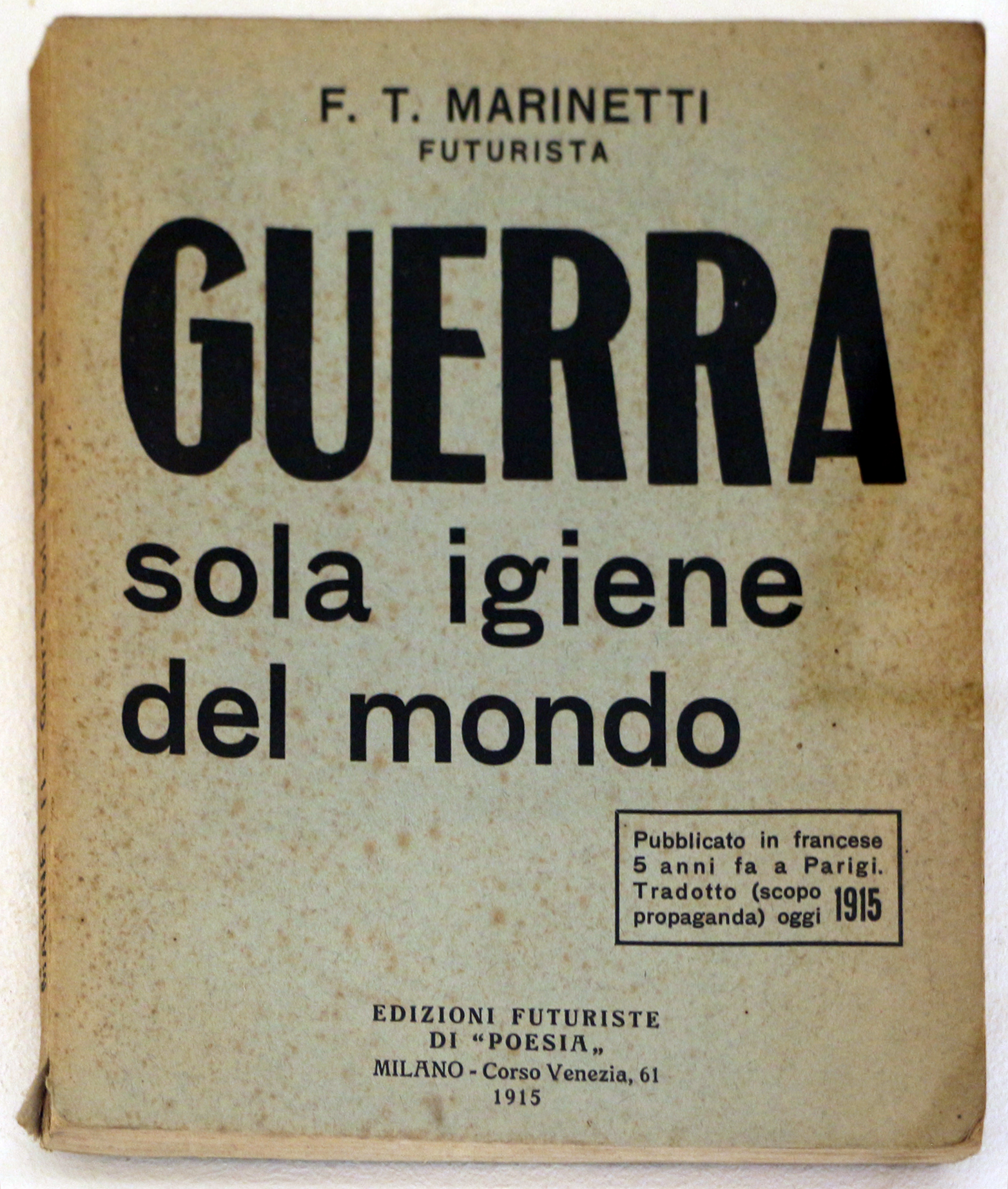

“War the Only Hygiene of the World”, Marinetti celebrated the onset of World War I and advocated for Italy's involvement