The news hit Rome last month as something of a shock: Antico Caffè Greco, the city’s oldest bar with a storied cultural and literary history, the haunt of Lord Byron, of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Charles Baudelaire, was, at least temporarily, closed to the public.

The bar’s previous managers, who had been engaged in a legal dispute with the space’s owner, the Israelite Hospital, over a major rent increase for almost a decade, had been forced to hand in their keys as the locks were changed. Representatives from the Israelite Hospital have promised that the bar will remain as it is, with minor improvements, and will reopen again to the public, but when and how that will happen remains to be seen. (Both an attorney for the former managers of Antico Caffè Greco and a press person for the Israelite Hospital did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

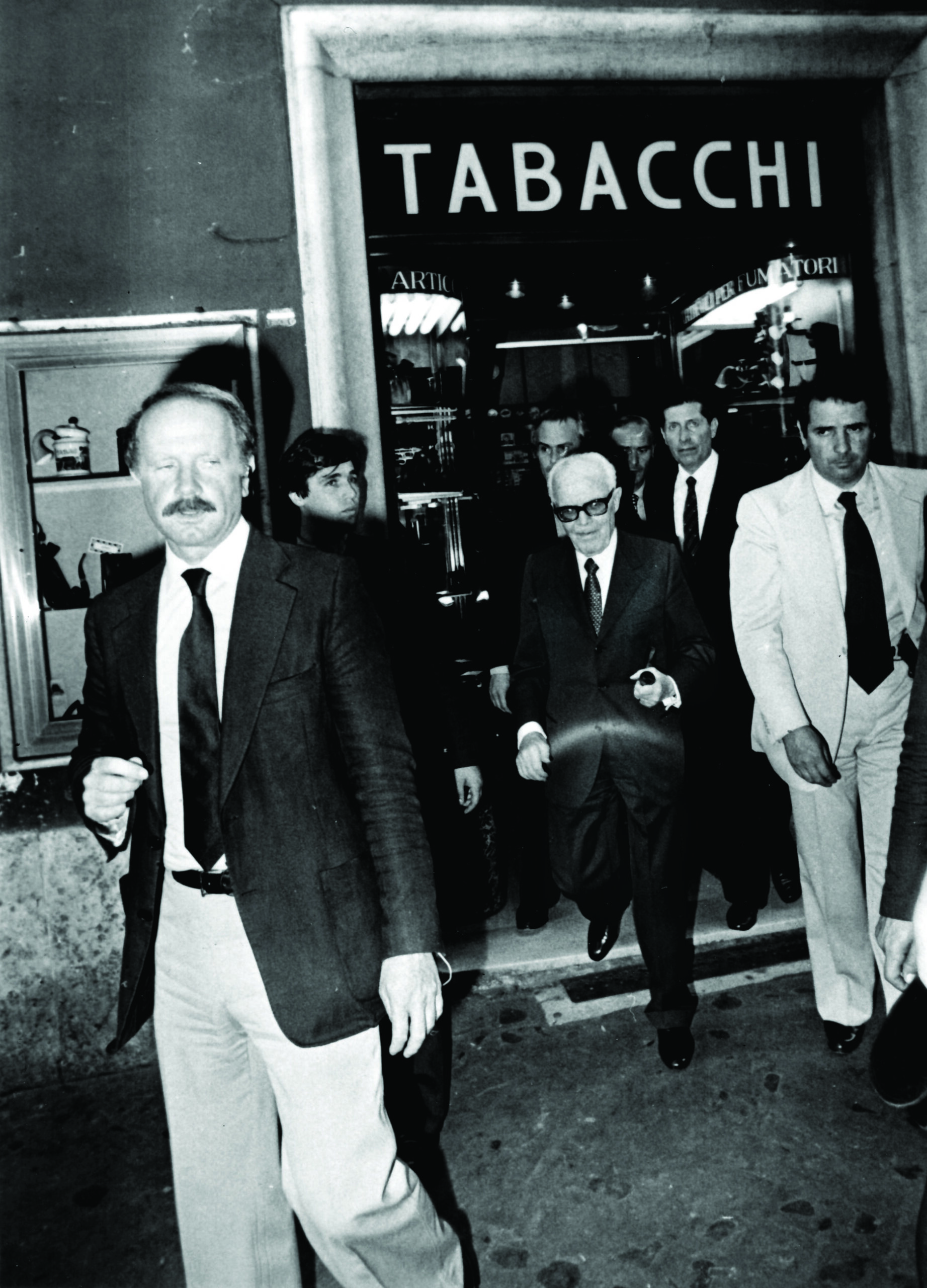

Caffè Greco in its former glory

The tragedy here, at least for the general public, is not the mere loss of an institution that opened in 1760 and has remained largely intact since that time, with much of the same decoration, furniture, and paintings. What is also lost is a piece of the city’s rich physical history as a harbor for international artists and writers.

Perhaps more worryingly, Caffè Greco’s closure, however temporary, is just one in a line of historic institutions that have shuttered or been at risk of closing in recent years due to changes in management and rent increases. While it’s difficult to get an exact estimate of these numbers, a membership list maintained by the national association Historic Establishments of Italy shows at least six historic hotels and bars, including Florence’s Harry’s Bar and Pisa’s 13th-century-house-turned-hotel Relais dell’Orologio, that have closed or changed locations in the last 10 years, per office manager Eleonora Zanchetta.

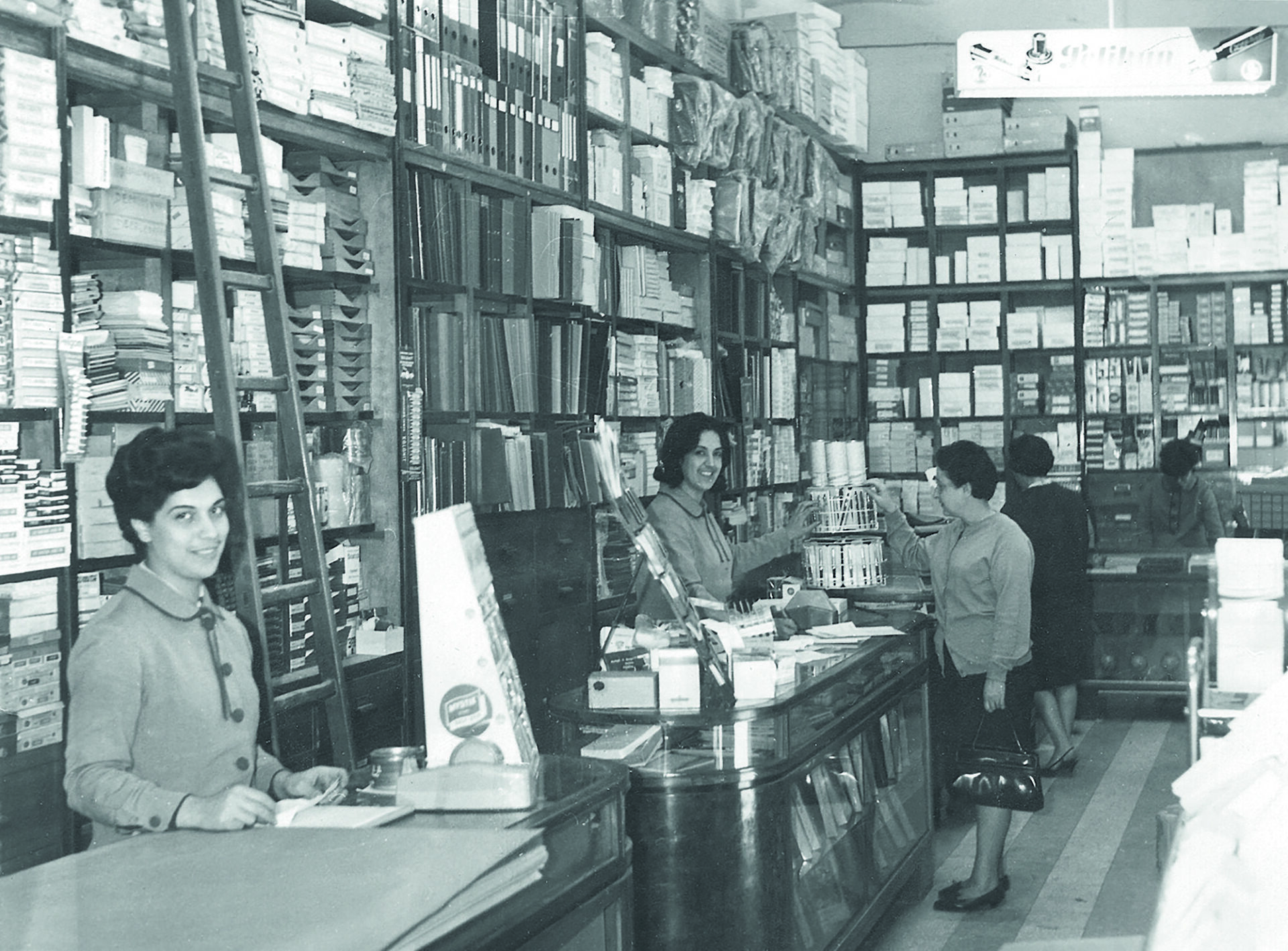

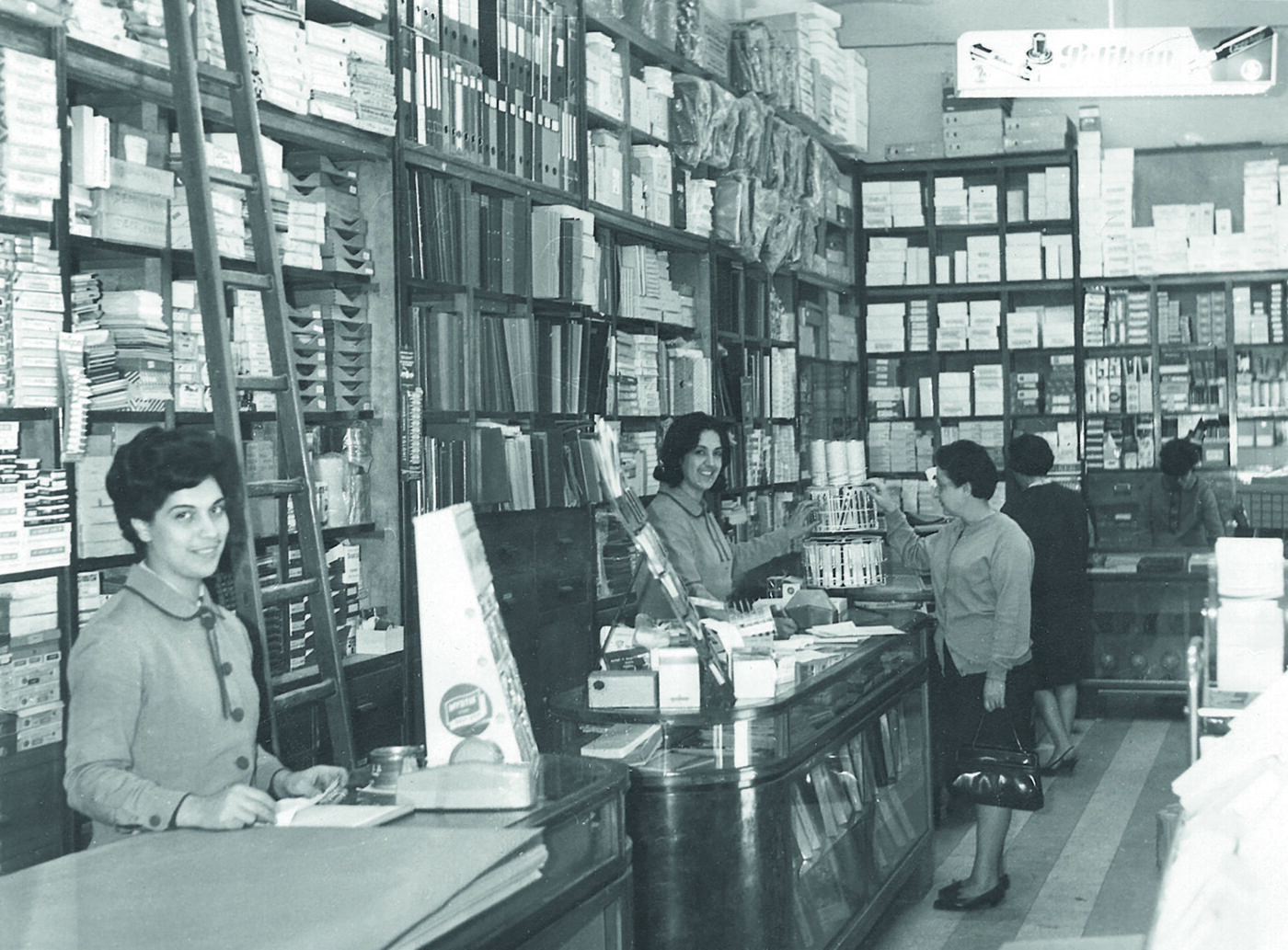

The ever-iconic Harry's Bar

Founded officially in 1976, Historic Establishments of Italy was intended to “bring together the most beautiful and oldest venues in Italy” in part “to protect and add value to this Italian cultural heritage,” said current president Enrico Magenes, administrator of Pavia’s historic Pasticceria Vigoni, whose owner created the “Paradise cake.” Founding members of the group included the then-owners of Caffè Florian, Italy’s oldest bar; Distilleria Nardini, the historic grappa distillery in the place of its origin, Bassano del Grappa; and Milan’s Savini, whose guests included Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini, and Gabriele D’Annunzio.

These institutions are historic in two senses of the word—they have both witnessed history and created it. Think of Naples’ Gran Caffè Gambrinus, which some say birthed the practice of “caffè sospeso,” the act of leaving a contribution for the next person’s coffee, or Milan’s Camparino, where Campari was first served, launching an aperitivo tradition.

Historic institutions call for historic bartenders; this one has been making Negronis and Garibaldis at Camparino for the past few decades

“The point is that they have intrinsic value for the history of the country,” Magenes said. “Of course, they are also attractive for tourists who come to Italy, because they are distinctive and unique, and the point is also to live an experience, to feel what is called the Italian way of living.”

In order to be a member of Locali Storici d’Italia, certain requirements must be met—the structure must have at least 70 years of continuous business, have retained in large part its original characteristics, and have been a “social and cultural gathering place,” per Magenes. The fourth, which is optional, is consistent management by the founding family.

At 43, Magenes has been around long enough to have seen some of the biggest venues fall, like Milan’s Trattoria Bagutta, whose business owners were evicted in 2010 after 84 years of enterprise. In its place is now a luxury clothing store.

In other instances, luxury brands have worked together with historic institutions to maintain them, like Milan’s famous Pasticceria Marchesi, in which Prada purchased an 80% stake in 2014, or Cova, the Milanese bar in which the LVMH Group bought a majority in 2013.

Window shopping at Milan's Pasticceria Marchesi

In recent history, outside efforts have also helped to preserve historic institutions. Two years ago, Rome’s famous Alfredo alla Scrofa, the rumored home of fettuccine alfredo, was under threat of eviction, in part because of Bulgari’s new hotel in the center of Rome. But the city, as well as the national historical association, stepped in to ensure that Alfredo would not close its doors.

“What scares me, however, are those that are not legally protected,” Magenes said. “…The problem is that, unfortunately, a bar may not be able to pay the rent that a fashion house can.”

Yet while Italy’s second-oldest bar may find itself under duress, the country’s oldest, Caffè Florian, has managed a path to success. Located in Venice’s Piazza San Marco and opened in 1720, the historic bar has only changed hands a few times in its 300-year history. In 2009, it was purchased by a group of Italian entrepreneurs, including Andrea Formilli Fendi, with intentions to make it an international brand, including two locations in Taiwan.

Perhaps what has helped Florian stay Florian is its two separate legal protections—one within the bounds of the Procuratie of San Marco, where it is mentioned by name, and another specific to the structure itself.

“The Superintendence is very interested in the conservation of Caffè Florian as an entity, in preserving the integrity of both its decorative components and the space itself as a living witness to history and culture,” wrote Cristiana Rivolta, who handles sales and marketing for the business, in an email.

In fact, protections by the various local Superintendences that handle cultural heritage have sometimes been the last resort for historic businesses. In 2019, the Superintendence of Florence recognized historic Florence literary cafe Giubbe Rosse as a cultural asset and moved to protect it through ministerial decree.

“Giubbe Rosse, with its decor among which was conducted literary and artistic organizing, represents a tangible testament to the atmosphere and intellectual fervor that animated Florence in the course of the 1900s,” reads a press release from the Superintendence noting the reasons for its protection. “The historic literary cafe holds through its very nature a strong, recognizable value as a meeting-place at all levels of society.”

The historic facade of Rome's Tebro Biancheria; Photo courtesy of the Locali Storici d’Italia

But when local arms of the Ministry of Culture do not step in, local associations can. That’s in part the role of Historic Shops of Excellence of Rome, founded in 2008 at the behest of a city councilmember who suggested to now-president Stefano Pizzolato to start an organization.

“Our goal is to make our businesses known to tourists coming to Rome, who may be Italian or foreign, but also to residents,” said Pizzolato, who is the co-owner of Tebro Biancheria, a luxury textile manufacturer and store in Rome. “After all, Rome boasts a presence of historic shops that no other capital city in other countries has in such numbers and with such history.”

Rome, the Eternal City—it’s usually used to express the city’s ancient history but, in this case, is possible to apply to its legacy of historic businesses. Much like Locali Storici d’Italia, the Roman association requires members to have at least 70 years of experience making the same products and that the store be run by the same family for at least three generations.

Inside Caffè Greco

But a keen observer to the site might note that Antico Caffè Greco was a member, although it did not meet the second criterion.

“That is the only exception in the association,” Pizzolato said, although later noting that Alfredo was another, “and, coincidentally, here’s how it turned out.”

Much like Magenes, Pizzolato is not overly concerned for Caffè Greco’s future, as he says the local restrictions imposed on the structure as a historic business give it little flexibility to be redeveloped into something else entirely. And while he disagrees that historic businesses at large are in crisis, a question he is often posed, what has certainly disappeared is the everyday visitor, in part due to the mass touristification of city centers.

“We have a very large flow of foreign visitors, which has obviously compensated for the loss of regular customers, because many Roman residents don’t want to come to the historic center anymore,” he said. “…The wealthy person who used to leisurely walk around the city center 15 years ago, 10 years ago, no longer does.”

In 2010, the City Council of Rome approved a resolution that, among other aspects, mandated that should a historic business close, the only commerce allowed in that space had to be dedicated to the same type of product. This restriction would only elapse once the venue had not been used for between five and 10 years, depending on its location. But, Pizzolato said, this was not enough to protect local business, as national law trumped the resolution and allowed for eviction in any case.

Now, both the local and national association are at work on populating a national register for historic businesses that would include not just stores but artisans and studios. Through this method of registration, relevant legislation could then be proposed, Magenes said, including establishing a lower tax rate for entities that are historic in nature.

“If a historic business is profitable and fully operational, why send it away?” Pizzolato said. “We risk losing a business that could be the symbol of a neighborhood or the symbol of a street.”