It’s perhaps a natural Italian bias to think that no food can rival the food of one’s childhood–whether that childhood took place in Puglia, Milan, or Rome.

But the relatively late unification of Italy and the disparate nature of the country’s regions have meant that food really does taste different based on its provenance. It’s not just a matter of supplì or arancini, risotto or tortellini in brodo, pasta alla norma or cacio e pepe–it comes down to the very land in which the food is made, and it’s a distinction that has been codified into European law.

There’s a reason why you’ve probably seen DOP or IGP labels on your food—these are indicazioni geografiche, or geographical indications, a set of food, agricultural products, and drinks that are recognized for where and how they are produced. To bear the name Parmigiano Reggiano, for example, the cheese can only be made in the provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Bologna to the left of the Reno River and Mantova to the right of the Po River. And if you are searching for the true Prosciutto di Parma, it’s not enough for the cured meat to simply have come from Parma proper–it needs to be produced in the territorio, within the province of Parma, at least five kilometers south of the Via Emilia, up to an altitude of 900 meters, delineated to the East by the Enza River and to the West by the Stirone stream.

The claim, at least by local producers, is that these precise geographic conditions and the techniques honed there over the decades, even over the centuries, is what ensure the respective product’s sought-after flavor profile. In the case of Prosciutto di Parma, for example, the Consorzio notes on their website that: “The quality and the characteristics of this product must be able to be traced back to this territory, as it’s truly in this area that the appropriate technical knowledge and ideal climate conditions exist for the drying, that is, the natural aging, that will give Prosciutto di Parma its sweetness and taste.”

But that very sweetness and taste is not a mere matter of subjectivity. It’s a legal restriction thanks to the intellectual property scheme that is geographical indications.

The stamp of approval on Prosciutto di Parma

In fact, roughly 3,894 food, drink and agricultural products in the European Union have or are seeking a registered geographical indication, per EU database eAmbrosia, maintained by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. Around 3,300 of these are registered products, including roughly 1,750 wines and 1,205 food items, per Olof Gill, a European Commission spokesperson for trade and agriculture. The primary indications are divided into two categories: the perhaps best-known protected designation of origin, PDO or DOP (denominazione d’origine protetta in Italy), in which every part of the production, processing and preparation process must take place in a certain area, and protected geographical indication, PGI or IGP (indicazione geografica protetta in Italy), meant for products in which at least one part of the “production, processing or preparation” occurs in a specific geographic area. Recognized products, other than wine, must bear a DOP or IGP label.

“Geographical indications are ‘products with a story,’” Gill said in a statement. “Consumers want cheese, meat, wine or whisky with a story–tales of the men and women keeping alive traditional ways of doing things, in the place they call home; stories reflecting history and heritage. A name recognised as a GI tells such a story.”

Perhaps no country tells more of a geographic agricultural story than Italy, which holds the highest number of recognized food products in the European Union, according to 2022 data from ISTAT, Italy’s National Institute of Statistics. That year, Italy had 319 recognized food products (up from 248 in 2012), followed by France at 262 and Spain at 205, per ISTAT’s most recent report. Those items represent around 81,400 producers in the country’s agricultural sector.

Once Italian products leave Italy, where do they tend to most commonly go? First in line is Germany, followed by France, the United States, Great Britain and Spain, per data from Coldiretti, Italy’s largest farmers’ union. The most commonly exported product is–unsurprisingly–wine.

Still, despite these impressive numbers, it’s worth noting that the bulk of the revenue–62%–from Italy’s geographically indicated products comes from only four items: Grana Padano, Parmigiano Reggiano, Prosciutto di Parma and Prosciutto di San Daniele, according to a 2018 academic article in Meridiana.

Grana Padano

How DOP works on the ground

In Italy, geographically indicated products are a big business. In 2022, the total production value of all DOP and IGP products in Italy reached more than €20 billion, per an annual report from Ismea and Fondazione Qualivita. This represented roughly 20% of the total revenue from Italy’s agricultural industry.

“We have a very strong connection here with the territory,” said Claudia Albani, head of European policy coordination for Coldiretti. “If we talk about geographic indications in general, they are important for our agricultural market and they represent a strong link with the territory and assure the provenance of the material.”

The current process involves applying first to national authorities and then getting approved by the European Commission, as set out by European Commission instructions. Applications can be questioned by anyone with a legitimate interest. But this very administrative path can lead to conflict, per some academics, since it requires a number of different sources to agree to a standard production method and area of production.

The history of DOP-like schemes also long predates the European Union and the European Commission’s regulation of them. In fact, it has its roots in 1887, when the French court of Angers determined that Champagne “referred simultaneously to the place and methods of production of certain wines specifically denoted by that name and by no other,” per the Union des Maisons de Champagne, the trade union of champagne producers. This was the first global example of designation of origin, at least by some scholars’ estimation.

In Italy, this idea didn’t achieve legal status until the mid-20th century, when denominazione di origine controllata (or DOC) was “regulated by the release of official stamps certifying their geographical origin,” like the D.O.C. stamp, writes Cristina Grasseni, a cultural anthropology professor at Leiden University, in a 2005 article. It was in 1992, the same year the Maastricht Treaty was signed, the official start of the EU, that the European Community began to regulate “authentic local products” under DOP and IGP, thus, in many ways, overruling local programs.

“Geographical indications embody the philosophy of caring about origin: in a globalized world, it is great to have food and drink that is different because of its origin,” Gill said in a statement. “Geographical indications are the opposite of a standardized restaurant chain meal, which tastes the same all over the world, made to a standard recipe.”

Statistics provided by EU spokespeople show that these geographical indications have even had an economic impact on the number of people who enter the agricultural field. The production of every 100,000 liters of milk yields around one job in the regular milk sector and roughly 2.8 jobs in the production of DOP milk. More young farmers are entering milk production for geographically-protected products vis-a-vis the rest of the dairy sector, according to data provided by Gill.

“Studies in Europe have shown that farmers and local producers feel a deeper connection to making origin products, given their link to local geography and culture,” Gill said in a statement. “This enhanced pride of place can provide a boost to a local area, not just for farmers but throughout the community.”

This also affects price–one EU study found that local producers could earn 2.23 times the price for a “famous traditional product” relative to the “comparable, non-local product.”

All signs point to Prosciutto di San Daniele

To be DOP or not to be DOP?

Still, while the economic impacts of geographical indications as touted by the EU are numerous and wholly positive, the reality is a far more complicated picture. In 2023, Grasseni published a study of two cheeses from Val Taleggio, both with DOP status: well-known Taleggio and lesser-known Strachítunt. While both of these cheeses had a geographical indication, that very same indication had differing effects. There is a utopian stereotype of geographical indications: uplifting young farmers, bolstering small family businesses, and diffusing a local culinary and agricultural history to a broader audience. But in the case of Taleggio, perhaps a victim of its own fame, Grasseni writes, “they feel their more ‘authentic’ production lost out to large scale industrial production.’”

Taleggio was one of the first cheeses in Italy to achieve a Denominazione di Origine Controllata, eventually being lumped into the EU’s quality scheme in the 1990s, per Grasseni. But its DOP status and “simple protocol” actually “lent itself to industrial scaling up,” particularly given what Grasseni calls its “very broad area of production.” From an economic standpoint, this makes sense–mass production was cheaper at “large-scale dairies” in the lowlands, where more cheese could be made at a lower cost. “Small-scale mountain family enterprises,” on the other hand, were too small to accommodate large batch production, particularly because they often produced their cheese by hand, according to Grasseni’s research, incurring additional expenses. In this case, one thing was clear: the DOP designation did not necessarily benefit the smaller-market producers.

Strachítunt, on the other hand, managed to maintain its intimate production, likely in part due to its lesser-known status. A group of producers formed to apply for DOP status in 2002, “taking stock of the lack of distinctiveness of Taleggio,” Grasseni writes, and choosing a geographic production area of less than 80 square kilometers in size. They only achieved this status 12 years later, in 2014. And while the DOP designation “does seem to have worked as an incentive to start up a dairy business in the valley,” Grasseni argues that it perhaps came too late. Instead, what has proven successful is a new form of marketing, focused more on “another kind of authenticity, simple, healthy, genuine, produced by small-scale farmers in one’s territory–farmers in need of help.” At the start of the pandemic, for example, the local farming cooperative took to Facebook in a call for online orders, delivered directly to the home.

“The vocabulary and register used, notably, did not evoke the prestige of their products, and the DOP certification of the local cheeses, either Taleggio or Strachítunt, was not even mentioned,” Grasseni writes. “It was also not mentioned which cheese was on sale of the many types available in Val Taleggio. Nevertheless, this notice triggered such interest that incoming orders soon overwhelmed the cooperative staff.”

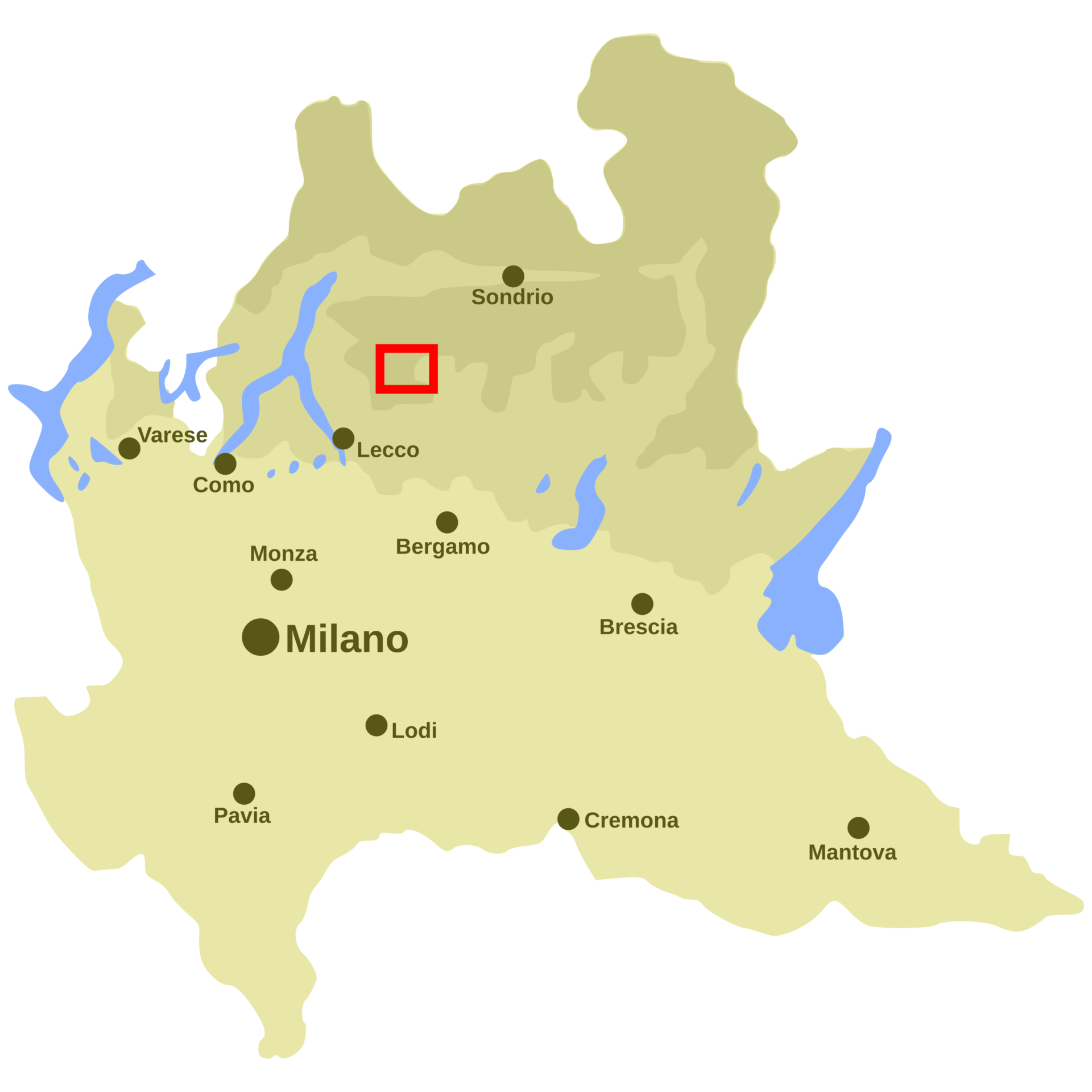

In Italy, some local products have instead chosen to renounce geographical indications altogether, like the famous story of Bitto Storico, now known as Storico Ribelle. A historic cheese that was even chosen to represent the Valtelline during the expo celebrating Italy’s unification, Bitto received a DOP designation in 1995, expanding both its traditional production process and its geographic area to the entire province of Sondrio. This led to higher output–from 5,700 Bitto wheels in 1996 to a relatively consistent rate of roughly 20,000 a year from 2009 onwards. But it also created conflict amongst producers, some of whom split off in 2003 to form a group dedicated to maintaining the historical Bitto. Still, it took 13 years of negotiations, fines for using the Bitto name, reconciliations, and an eventual rupture for a decision to be made. In 2016, Storico Rebelle, the new Bitto Storico, was formed, officially breaking off from the Bitto DOP. The story of Bitto became an example of the scaling influence of a geographic designation, of the way in which DOP could theoretically discourage the very traditional production it aimed to promote. Storico Rebelle now has its own Slow Food Presidium.

But the future of geographical indications in Italy and across Europe centers on another steadily-fought battle in recent years–against “Italian-sounding” products on the global marketplace. These are products, like Parmesan, that resemble Italian-made items, with a similar name, taste, and texture, but are not made to the same specifications. In 2023, the fake “Made in Italy” food market was worth roughly 120 billion euro, per Coldiretti, about double that of Italy’s own.

“It’s clear that we are the ones who have to suffer the economic consequences,” Coldiretti’s Albani said. “And it’s obvious that there is a problem of transparency for the American consumer that buys parmesan with a nice Italian flag on it.”

In April, the farmers’ group organized a protest of thousands at the Brenner Pass, the border between Italy and Austria, calling for an end to the sale of “foreign food falsely called Italian while the European Union puts the label at risk,” per reporting by EuroNews. At the same time, Coldiretti launched a European citizens’ initiative seeking regulatory changes, including increased border checks on food entering Europe and national borders and the mandatory display of the country of origin on all food products. The proposal has until late September 2025 to collect one million signatures, with specific thresholds by country, in order to be considered by the European Commission.

“This is a historic battle born from the pact with consumers,” Albani said of Italian-sounding products. “On the one hand, it concerns the consumers and, on the other hand, it’s about our own manufacturing system.”

The red square shows the original production area for the Bitto Storico cheese; Photo by Luigi Chiesa