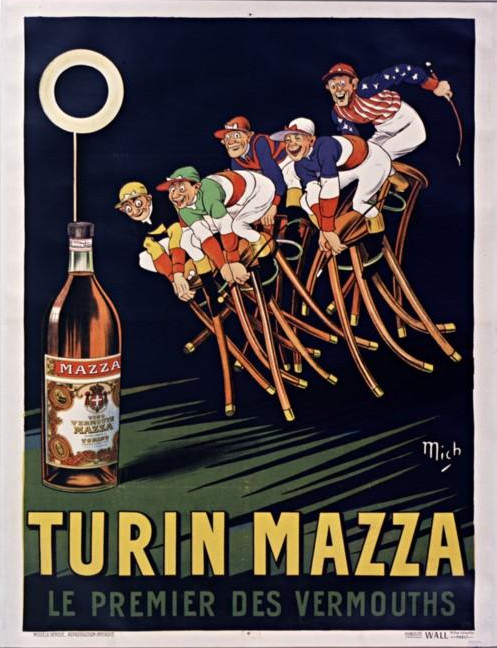

Picture Turin, the 1780s: a cosmopolitan city, capital of the Kingdom of Sardinia, known for its eminent university and for its Teatro Regio, which seats an impressive 1,500 people for operatic performances.

In 1780, Caffè Fiorio opens as a salon catering to the intellectual and political classes. Visitors include Nietzsche and Camilo Benso, Count of Cavour, one of the leading proponents of the risorgimento. To fuel their debates, the men drink vini aromatizzati. All around Piedmont, small laboratories and pharmacies are making these aromatized wines, each crafting their own super-secret version with local botanicals.

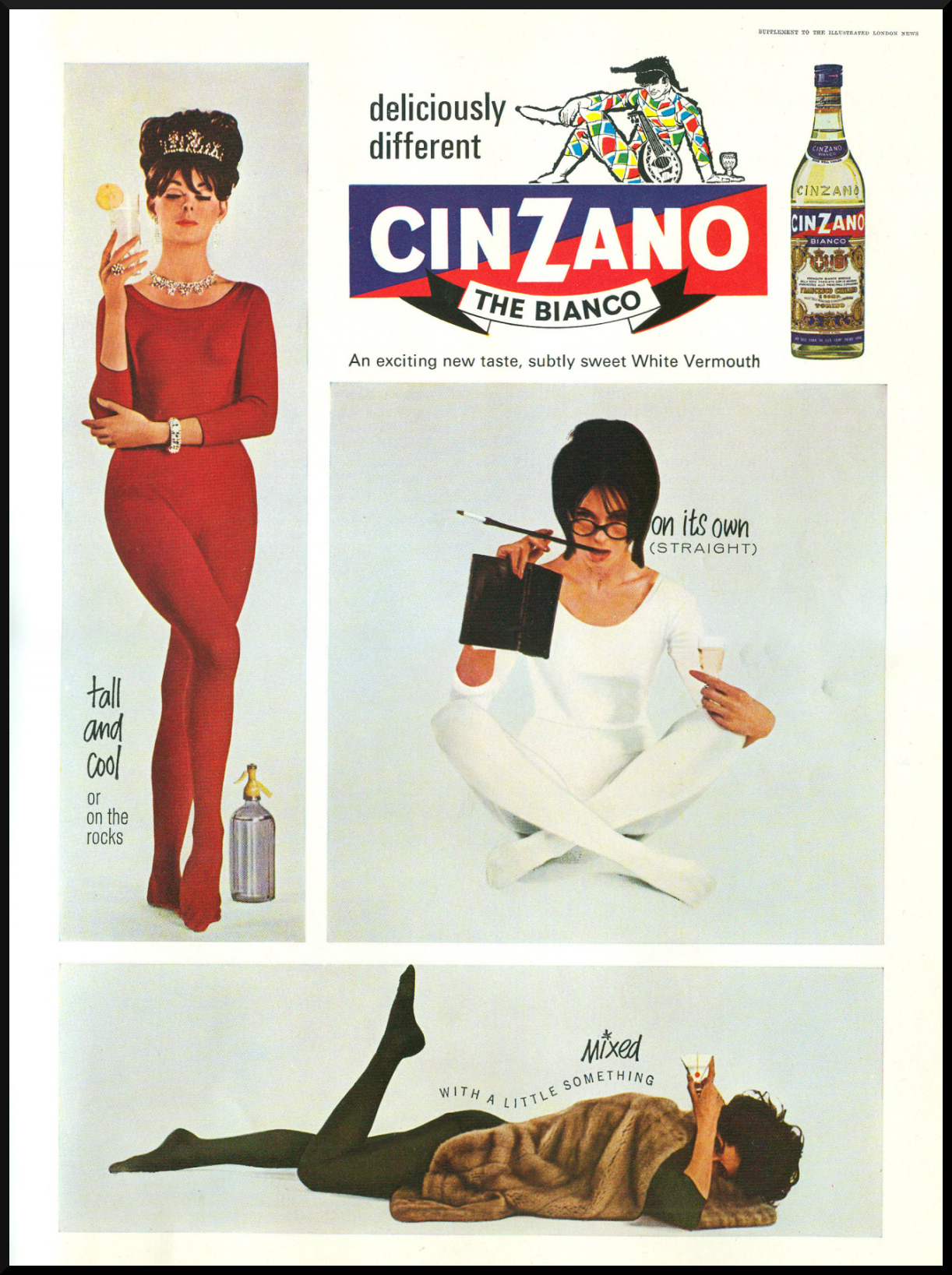

In 1786, Antonio Benedetto Carpano, a Piemontese herbalist by trade, sees a problem: women don’t drink vini aromatizzati. Perhaps if he makes the drink sweeter, they’ll be tempted? By soaking botanicals in spirit, then adding it to aromatic moscato wine, Carpano perfects a recipe for what he calls vermouth. King Vittorio Amadeo III becomes a fan (his Royal Palace happens to be across the street from Carpano’s lab), and, by the time the French have taken over Turin, a glass of vermouth is the preferred aperitivo drink of the city’s residents.

Not only a nice drink in the evening, vermouth–named after the German word “vermut” for wormwood, one of the primary ingredients–was considered a medical supplement. Recipes were engineered to address specific concerns. Bitter herbs such as gentian and wormwood, for example, were considered digestive aids. Quinine, which forms the base of the Piemontese aromatized wine Chinato, is still to this day used to treat malaria.

Vermouth is now a wide-ranging drink–notably added to Martinis across the world, softening the flavor of gin or vodka–and sweet vermouths like Cocchi di Torino have become a mainstay for the world’s favorite cocktail, the Negroni. Today a wide range of artisanal vermouths are produced across Italy, and while they all have their own unique variant, the common factor is: a base of wine supplemented with a neutral spirit infused in a secret recipe of herbs. Common botanicals include the necessary wormwood as well as gentian, citrus peel, coriander, cinnamon, peppercorn, and quinine.

Negroni

There’s one Torinese laboratory, however, that stands out for its multi-generational devotion to making truly artisanal aromatized wine: Chinati Vergano is a tiny operation founded by Mauro Vergano, a chemist who spent years researching botanical flavor combinations while working in the pharmaceutical industry; formerly based out of Asti, they’re soon to open a laboratory-tasting room in Turin. Since 2003, Chinati Vergano has been using natural wines as the base for their vermouths, which is not only an achievement in environmental terms–natural wines being made from organically farmed vineyards and fermented without additives–but it’s also impressive, technically speaking.

Consider that a vermouth is meant to be relatively consistent year after year, with its herbal recipe being the stand-out attraction–but for Chinati Vergano, working with natural wines, which vary from one vintage to the next due to their ecological and handmade aspects, no base wine is ever the same, which means constantly being attentive while tasting and blending. “It’s a challenge to make a product that’s always the same from a product that’s always different,” says Tommaso Vergano, who now helms the Chinati Vergano operations, referring to this choice.

Local flowers for vermouth; Photo Courtesy of Chinati Vergano

Tommaso continues to develop relationships with natural wineries for the product bases while exploring traditional vini aromatizzati in new ways. Adding to their signature products–the savory, Grignolino-based, wormwood-heavy Americano; a gently sweet white vermouth called Luli made with moscato; and their Chinato, a traditional Barolo product featuring gentian, quinine, rhubarb, and warming spices like cloves, cardamon, and mace–Chinati Vergano has recently dug back in time to produce a line of throwbacks to the early days of aromatized wines in Piedmont.

In this vein, they have released a Centeherbe, which, per the name, was originally made by monks with 100 different herbs and was once considered a remedy for the plague or the flu, with an overall flavor that’s strong and Christmassy. There’s also a Genepy, an Alpine aromatized wine made by a “cold maceration of herbs into alcohol and water,” featuring Alpine wormwood and achillea moschata, a type of yarrow. And they’re making an Elisir China, which translates to “quinine elixir,” a bitter tonic for anyone concerned about their exposure to mosquitos on a warm summer’s night.

Tommaso foraging for herbs; Photo Courtesy of Chinati Vergano

A well-made vermouth can be enjoyed simply: sweeter styles are great on the rocks and with a citrus wedge or twist (alternately: with a fat green olive on a toothpick) and potentially the addition of tonic. To play around, take a cue from Padova’s natural wine bar Brutal, which uses Chinati Vergano’s Americano in a house spritz. In Ibiza, restaurant Casa Lhasa’s only house cocktail is an Americano Pét-Nat Sbagliato featuring Chinati Vergano. Natural winemakers across Italy (and the world) are also coming out with their own vermouths (look for one by Raina in Montefalco or the vermouth variations released by COS in Sicily).

Thanks to its versatility, vermouth has well earned its place in the realm of aperitivo cocktail culture–an indispensable pairing for salty olives, anchovy soldiers, or crostini–and yet it’s for this very reason that it’s often underappreciated as a drink in its own right. The aromatized fortified wine is thankfully coming back in vogue, however, at the hands of contemporary vermouth makers like Chinati Vergano, who look back to look forward, capturing the traditional reverence for medicinal herbs. So, next time you need a drink to bridge the afternoon and evening, choose vermouth; with a scarlet-red drink in hand, its aroma mingling with an orange slice garnish, you can pretend, if only for a moment, that you’re in 18th-century Turin, stimulating not just your appetite but your intellect.

Photo Courtesy of Chinati Vergano