Words are not just tools for describing our surroundings; they create intricate worlds within the minds of their creators. Language serves as a vessel for our emotions, memories, and dreams. This concept finds its remarkable embodiment in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities or Le Città Invisibili. Originally published in Italian in 1972 and translated into English two years later, this concise 170-page work may seem easily digestible at first glance, but its depth transcends simplicity. A casual skim won’t suffice to grasp its essence. Calvino’s masterpiece is a profound exploration of the potency of words to navigate the intricate boundaries between reality and imagination.

Born in Cuba but adopted by Italy, Italo Calvino ranks among the most cherished and widely translated Italian writers. On a relentless quest for innovation in literature, Calvino experimented with metafiction and narrative structure, was a master of wordplay, and ventured into various genres, from combinatory literature (in which he melded disciplines like mathematics, science, and music) to travel writing and magical realism.

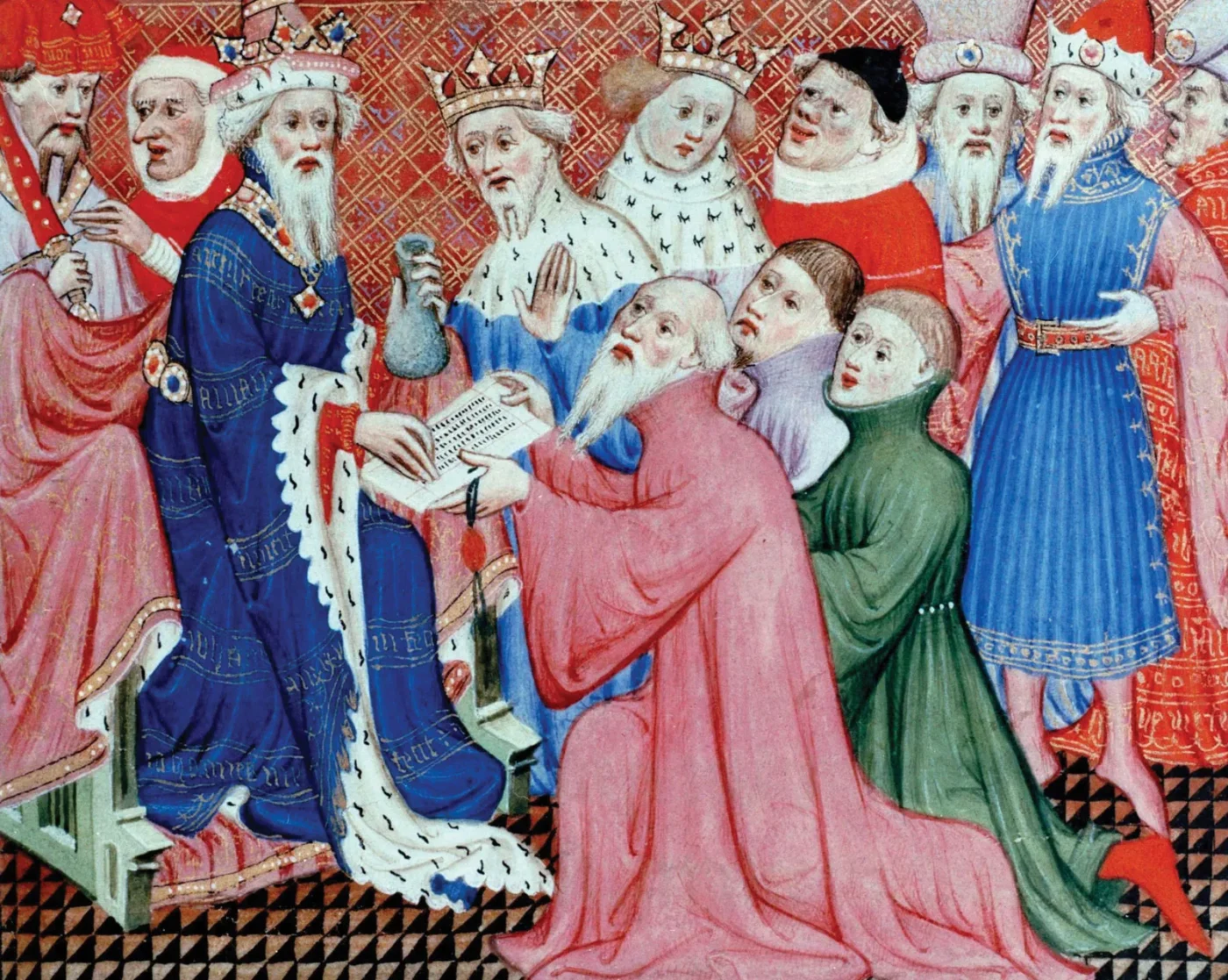

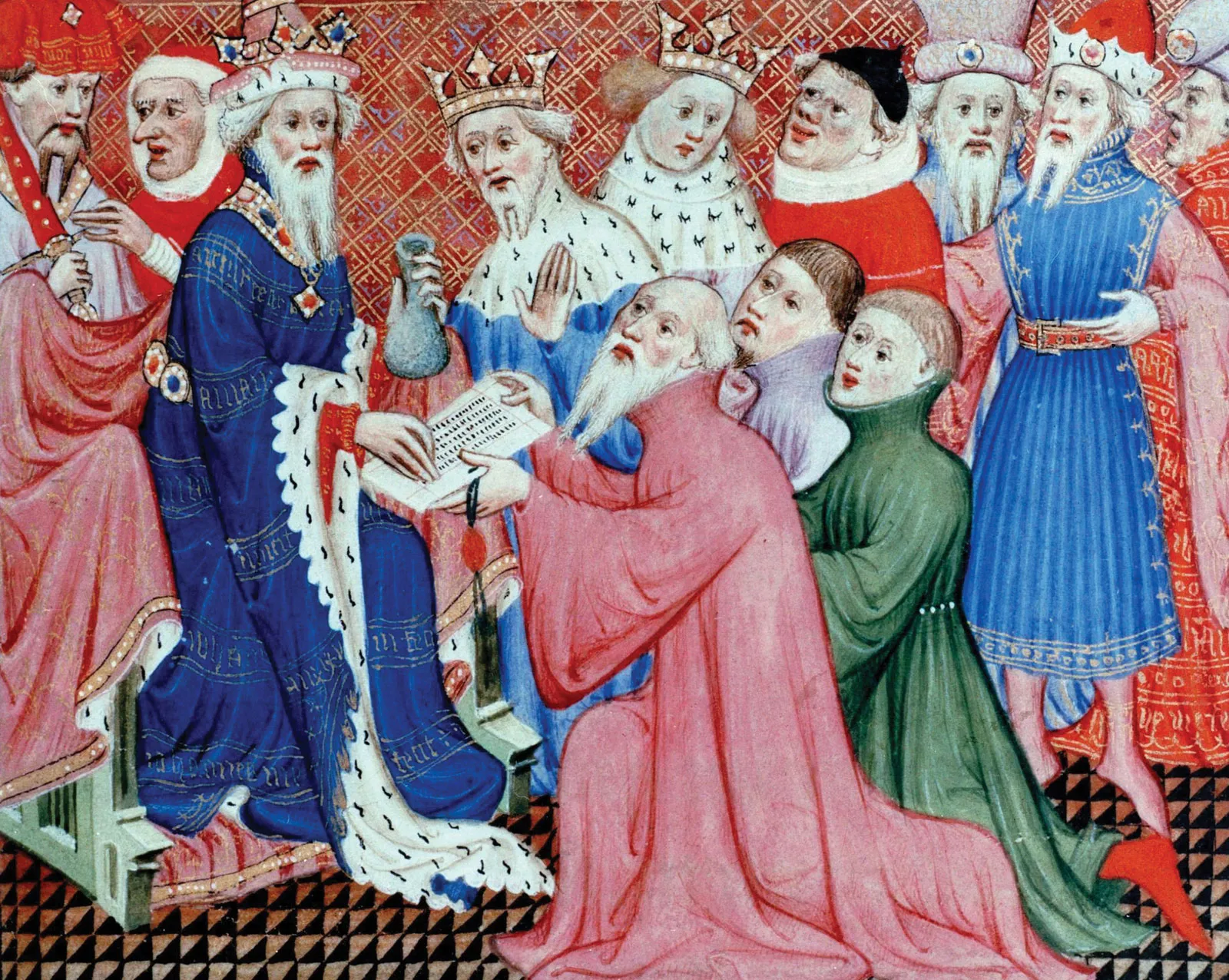

But despite his vast literary repertoire, it is Invisible Cities that is considered to be his masterpiece. Adopting the perspective of one of the earliest travel writers, Marco Polo, Calvino’s work unfolds as a travelogue, leading readers to places that straddle existence and non-existence. In 1271, Marco Polo departed from his native Venice, embarking on a 14-year journey along the Silk Road that led him not only across vast distances but also into an entirely new world. Thanks to his intellect and connections, he was appointed emissary to Kublai Khan, the Emperor of China’s Yuan dynasty, who sent him on missions throughout Southern Asia. When Marco Polo eventually left Khan’s court, his return journey took him through Persia and Constantinople (now known as Istanbul). The sum of these extraordinary encounters and experiences were documented when Marco Polo recounted them to a fellow inmate in a Genovese prison; his account was later published in a book known as Il Milione, or The Book of Marvels of the World.

Marco Polo’s descriptions of these foreign lands serve as the foundation for Italo Calvino’s fantastical narratives, particularly his tales of “invisible” cities. The novel takes the form of an imaginary dialogue between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan, during which the Venetian entertains the emperor with stories of the places that he has visited, and of the journeys he has made. Only at the end of these discourses do we find that the invisible cities are, actually, one invisible city: Venice. “Every time I describe a city, I am saying something about Venice,” Polo admits.

It seems only fitting to liken a place as complex, as layered as Venice to 55 different cities. Countless words have been dedicated to La Serenissima throughout history, and yet it never seems to be enough: regardless of how often Venice has been written about, there will always be another writer seeking to eulogise it. It seems perhaps to be a place that is impossible to encapsulate in words. What the city evokes is beyond description.

It’s not surprising that Invisible Cities was never conceived as a complete novel. Rather, it was envisioned as a collection of separate poems or, in the words of Italo Calvino, “a series of verbal reports.” These descriptions were not written sequentially; instead, they were accumulated over time, akin to building a scrapbook. When Calvino deemed he had gathered enough material, he categorised them into various themes: memory, desire, signs, eyes, names, the dead, the sky, continuous cities, hidden cities, thin cities, and trading cities. To add complexity, Calvino emphasised that Invisible Cities is not a novel, but a space in which the reader can freely wander… A little like the city of Venice itself, there are no specific routes from A to B, only meanderings through hidden calle, campi, and sottoportegi.

Calvino named his 55 imagined cities after women–Euphemia, Octavia, Irene, Berenice–each of which accentuates different elements of Venice: “a city of pure gold, with silver locks and diamond gates” (Beersheba), “a city of water, a network of canals” (Esmeralda), “a white city, well exposed to the moon” (Zobeide). These cities’ beauty is overwhelmingly feminine, and after all, Venice is female: La Serenissima is her name. Here, Calvino subtly accentuates a linguistic trope, that of the tendency to associate feminine language with beautiful places and objects, of using a female framework to evoke grace, elegance, and softness.

For someone not already intimate with Venice, Calvino’s descriptions might be difficult to reconcile with the city itself. Yet as much as these cities are removed from the actual bricks and mortar of Venice, the choice of language serves to suggest her essence. More importantly though, it must not be forgotten that this is an entirely personal description of a city. Calvino himself described Invisible Cities as his “own love poem to a city that has become increasingly difficult to live in.”

I have read Invisible Cities in both Italian and English. Though Italian is not my madrelingua and there are some grammatical rules that will forever evade me, I can tell you one thing for certain: the Italian and English written registers are worlds apart. The flow of the words, the construction of the sentences is by necessity lost in translation. To take things further, the use of the female in Italian to describe the imagined cities–as in “l’uomo arriva a Zobeide città bianca ben esposta alla luna”–simply does not register in the grammatically ungendered English. The nuance, then, of a male writer describing his way through a female place only works when we read a copy of Le Città Invisibili in its native tongue. In reading Calvino’s vision of imagined places in English, we see the city, once again, in a different way–a 56th version, if you will.

In essence, Invisible Cities is a mirage—a journey into Italo Calvino’s fantastical portrayal of Venice. It does not serve as a conventional travelogue or city guide; instead, it confirms that Venice is as much a work of art as it is an architectural entity. And so Invisible Cities is a treasury of memories that will persist and evolve within the reader’s mind, existing in as many nuanced permutations as there are people who read it–much the way Venice shows a different face to everyone who passes through.