There’s a supposedly great restaurant in the next town over from where I live in the Marche region that I’ve always wanted to try, where the owner cooks and serves the meat-focused dishes himself with much fanfare, personality, and charm. My Italian partner outright refuses to take me there out of what I believe is a very valid fear of us being kicked out for my pescatarian, gluten-free dietary leanings. The owner is apparently so insistent that everyone should eat large quantities of meat and pasta that requesting anything else would be an insult to his cuisine and culture, and rightly so. This kind of devotion towards food and local, time-honored fare is not uncommon in Le Marche–like all of Italy, it holds its own particular cuisine and traditions as sacred.

I’ve lived in a small hilltop town in the Marche region of central Italy for over four years now and have been a frequent visitor to these parts for well over a decade. Getting to know this relatively undiscovered, lesser-visited region has always felt like having in my possession a very good secret. It has all the ingredients for what many of us are seeking when we travel, especially when we travel in Italy: authenticity, so many stories to tell, and a zero-kilometer, eco-friendly attitude without even trying. And this is reflected best in the food. Locally sourced, made for the pure love of savoring it, sharing it, and continuing very old traditions, food here is never tweaked for tourist taste buds, as there just aren’t that many here.

Food in Le Marche is affordable and, at its best, hyper-local. A unique breed of wild mussels are harvested along a small stretch of the Adriatic, while inland treasures include a protected varietal of sweet fava bean, grown in white-clay soil, and abundant truffles found in the oak forests around one small town. There’s a coastal city with a proud fisherman soup tradition, a flaky flatbread born in a Renaissance town, and deep-fried olives made great by a superior local green olive.

You can pin each of these delicacies to a dot on the map, making their hometowns destinations in and of themselves. To try them all, hit the following six spots on a sort of progressive dinner (or lunch!) road trip over three or four days, starting in the North in Urbino, then Acqualagna, Fratte Rosa, Fano, and Portonovo, ending South in Ascoli Piceno. Or, you could focus on the coastal spots in summer–from Fratte Rosa to Fano to Portonovo Beach, ending in Ascoli Piceno–while reserving Acqualagna for its October-November truffle fair with a side of steaming hot flatbread in nearby Urbino afterwards. This is how to eat your way through Le Marche.

Courtesy of Katie McKnoulty

Wild Mussels in the Riviera del Conero

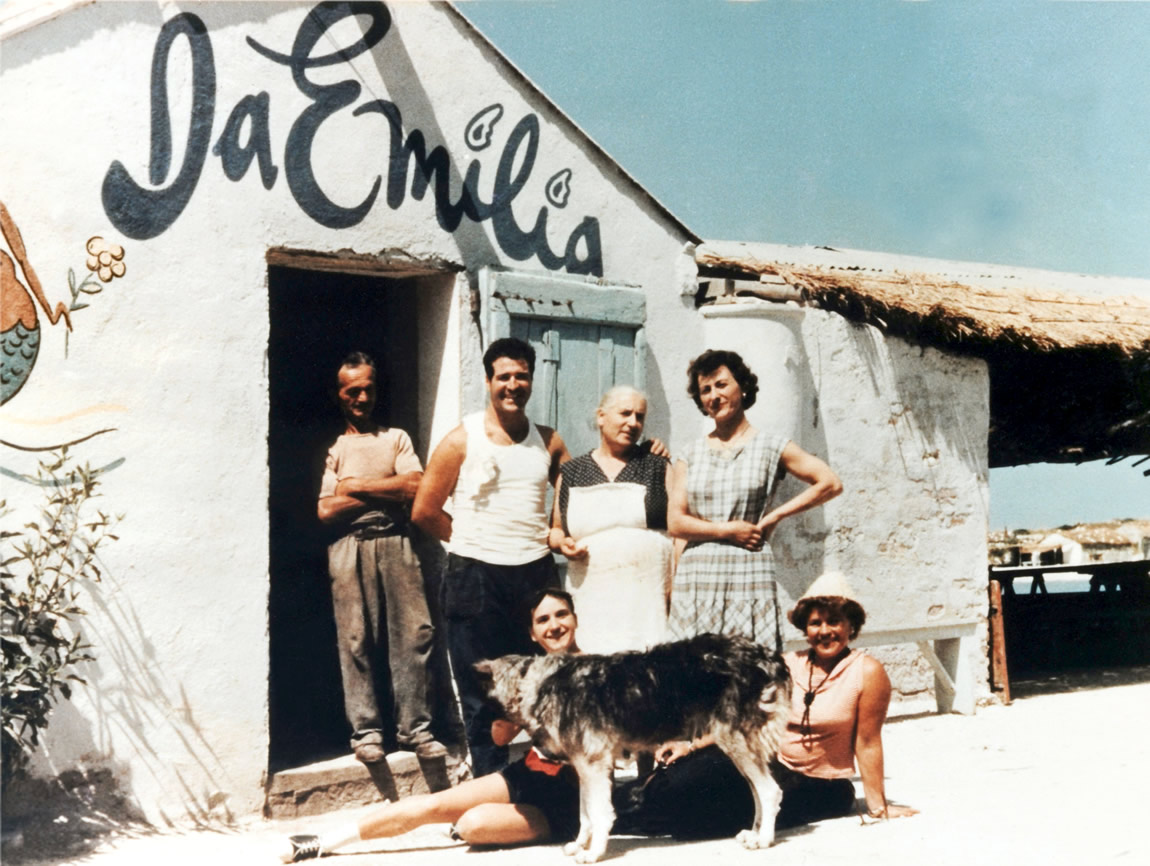

Our first stop is Portonovo Beach in Marche’s Riviera del Conero on the Adriatic coastline, the prettiest of a series of white-pebbled bays boasting calm, clear waters, backdropped by wild, natural surrounds and the cliffs of Mount Conero. Portonovo Beach is a retro 1960s Italia dream, all blue and yellow striped umbrellas and coin-operated outdoor shower stalls, where kids play on small pedal-powered boats from another time.

It was here on this beach in 1929 that local entrepreneur Emilia began roaming the shoreline selling her panini and drinks to beachgoers, an enterprise that would morph into her restaurant, Da Emilia. A local institution, the summer-only restaurant is famous for serving Slow Food Presidio moscioli (wild mussels) unique to the Conero coastline, with wild mussel fishing now limited to very few stretches of coastline, not only in Italy, but throughout the world. The mussels, smaller than other varieties and especially sweet, are pried fresh every morning by hand from nearby submerged rocks, accessible only by boat, and are served in Emilia’s signature moscioli sauce over spaghetti.

I’ve been coming to Da Emilia with my family since we first started holidaying in Le Marche over a decade ago; it quickly became my favorite restaurant. With the veranda directly on the beach, you sit so close to the sea that the waves almost lap at your feet; the perfect spot to watch the busy beach scene outside.

Courtesy of Da Emilia

Fish Soup in Fano

Pass through the ancient Arco di Agosto dating back to 2 AD, the gateway to the coastal city’s walled centro, and you’ll find Fano’s most famous dish, Brodetto alla Fanese, on the menu at many a trattoria down cobbled lanes and along the beachfront. A tomato-rich broth filled to the gills with a smorgasbord of the Adriatic’s best seafood, the dish was born aboard fishing boats as a “meager” dish fishermen concocted to use their catch too small or damaged to sell. All these leftovers were cooked in a pan with oil, onion, tomato paste, and vinegar without being shelled or fileted, and eaten with stale bread to mop up the last of the glorious broth.

My favorite place to eat this dish is at Trattoria La Quinta at the port of Fano where boats line the waterways. Dine next to businessmen sharing a meal with colleagues, families celebrating a birthday or Sunday lunch out, or older couples, the weekly regulars. The soup has been the principal dish of the restaurant since the 1950s, using Signora Quinta’s original recipe handed down through generations.

To try the city’s many different interpretations of the dish, head to the annual BrodettoFest taking place every summer in June, celebrating the fish broth, a part of the city’s history as much as the palaces, churches, Roman architecture, and ruins dotted around it.

You could always chase your brodetto with a moretta too, a digestivo also native to Fano made with piping hot espresso, rum, anise, and brandy, another fishermen’s tradition used to warm up before setting sail on the Adriatic.

Fano, Marche

Truffles in Acqualagna

While Alba in the northern Piedmont region may be Italy’s most famous truffle hotspot, the Marchegiano town of Acqualagna and its surrounds actually account for two-thirds of the country’s annual truffle production. The hills above the town have been known for their truffles for centuries; the unique climate and soil in this small area and the abundance of oak trees make it an especially hospitable place for truffles growing underground.

The National Truffle Fair of Acqualagna every autumn celebrates both the white and black truffles found in the area, seeing international experts and local enthusiasts of the earthen delights descend upon the small town backdropped by the Apennine mountains.

Stalls selling the strange-looking gems and their products line the streets and piazza. Local dishes like polenta, crostini, and handmade tagliatelle (another Marche specialty) topped with truffle shavings—pay extra for the more complex and rare white truffles—are served, steaming hot, in the cool November air.

Meanwhile, truffle hunters set out on foot with their dogs early in the morning during these months in pursuit of the elusive, edible treasures in the untouched Apennine woods. Local truffle stores like Acqualagna Tartufi also offer experiences to accompany hunters on their morning explorations.

Courtesy of Katie McKnoulty

Fava Beans in Fratte Rosa

Another Slow Food Presidio product found in the region is the favetta, meaning small fava bean, from the town of Fratte Rosa perched on a hill between two valleys, and the place I call home. The town and the surrounding land benefit from a unique, nutrient-rich white clay soil, which they’ve been using to make terracotta since ancient times. This same soil is responsible for producing the sweetest, tastiest fava beans, and a group of custodian farmers in town have set to work saving a historic, pure variety of the seed, safeguarding it as part of the biodiversity heritage of the Marche Region.

Locals know the best favetta are grown on the Lubachi hills just outside town (with some of the best views around), a point driven home by the popular saying: “dai Lubachi la fava veniva più buona”, “the fava is better from the Lubachi (hills)”. Rosatelli father and son team Rodolfo and Nicola make up Azienda Agricola I Lubachi working those very hills, their family has been farming here for as many generations back as they can trace, and, in 2000, they led the charge to save the Fratte Rosa fava seed. In Nicola Rosatelli’s words, “This very particular type of broad bean stands out for its tenderness and sweetness, and while the hybrid fava we find in the supermarket has 12 beans inside and is very narrow and long, the Fratte Rosa fava pod is short and stocky and has five beans, so it’s much tastier as the flavor is more concentrated.”

For decades, the Fratte Rosa favetta bean represented a staple food for the locals: fresh or dried, it featured in many home recipes. For me, the Lubachi fava pâté spiced with chili or the fava sott’olio infused with fennel is something I often pick up from the farm’s cute shop nestled in the green fields. In May, our town’s corner shop has crates overflowing with fresh, sweet fava, and we eat the beans accompanied by salty sheep’s pecorino cheese with our aperitivo.

The fava flour pasta, tacconi, is another speciality found locally at Osteria Mamà, or there’s a favorite dish of mine, fave in porchetta, served at Osteria Cianni Tartufi e Figli, an ancient Marchigiano recipe of fava stewed with wild local fennel and pancetta.

Courtesy of Katie McKnoulty

Olive All’Ascolana in Ascoli Piceno

These fried olives from Ascoli Piceno are made with an essential ingredient, the local green Oliva Ascolana del Piceno DOP. Both tender and crisp with a slightly bitter aftertaste, it is one of the most prestigious olives in Italy, grown in the land surrounding Ascoli Piceno town. They’re pitted and stuffed with fried meat and parmesan, breadcrumbed and deep-fried to crispy perfection to make the popular aperitivo companion, usually served in a paper cone.

While the recipe originated in the 19th century as a luxury reserved for the wealthy, nowadays the olive all’ascolana is more of a street and aperitivo food for all–and one of Le Marche’s most famous culinary exports. Looking out onto what is surely one of Italy’s most impressive squares–Ascoli Piceno’s Piazza del Popolo–at aperitivo hour with a crisp glass of verdicchio in one hand and a piping hot fried olive all’ascolana in the other is an unparalleled experience.

The terrace of iconic Art Nouveau-style Caffè Meletti in one corner of the square is the perfect place for said aperitivo, Ascolano style. The likes of Sartre and Hemingway once passed through the doors to sample their famed Meletti Anisette liquor, famed for sparking the imagination, a drink to finish things off on a high note.

Courtesy of Katie McKnoulty

Crescia in Urbino

As the long-running feud between neighboring regions Emilia Romagna and the Marche for the title of best flatbread rages on, you can try Le Marche’s best contender: the crunchy yet soft Crescia di Urbino made in hilltop Renaissance town Urbino. I referred to it as “croissant bread” when I first arrived here for its flaky, oily quality is more indulgent and textured than its Romagnolo rival, the piadina, thanks to the extra handful of pork lard used.

The ancient recipe dates back to the era of the Duke of Montefeltro in the 1400s as a food for the rich featuring pepper, a luxury spice at the time. It’s thought to have been served at sumptuous banquets at Montefeltro’s Ducal Palace (now an important art gallery) during the height of the Italian Renaissance.

Pop into one of the many crescia shops, joining the university students filling up on the hot sandwiches between classes. Most likely, your crescia will be filled with another local specialty, mild and creamy Casciotta di Urbino cheese, alongside other meat or vegetable fillings. It’s a delicacy to hold in hand, perched on the steps in the sun or walking the undulating, cobbled streets of Urbino, admiring the views.

Just don’t make the mistake of calling it a piadina as I have on occasion over the years, or you will be sternly schooled on the matter.

Urbino, courtesy of Katie McKnoulty