There are few things that spell Italian know-how and brilliance, that special talent Italians seem to have for producing beautiful and useful things, as well as Italian design. Today, Italian design represents a multi-billion dollar industry, celebrated and admired the world over. Its great practitioners—from designers Enzo Mari (1932-2020) and Ettore Sottsass (1917-2007) to entrepreneurs such as Alberto Alessi (b. 1946) or Dino Gavina (1922-2007)—are routinely graced with retrospectives and catalogs in Italy and abroad, as well as reeditions of their work. One might even say that Italian design has become somewhat of a brand, living off the spoils of a time that feels almost unrepeatable.

A product of the Economic Boom—that cycle of extraordinary economic growth which in the span of two decades tripled Italian income per capita and turned a still-agrarian society into an advanced industrial power—Italian design was not just there to serve Italians’ newfound hunger for benessere and purchasing power, but, in a way, to give it shape (pun intended). And it was as a result of this particular juncture—in which burgeoning demand for consumer goods combined with ideas of a new society and the influence of the avant-garde—that a class of enlightened entrepreneurs started to work with the likes of the brothers Castiglioni, Enzo Mari, and king of 1980s postmodern pop Ettore Sottsass, who was given a start by no less than Adriano Olivetti (1901-1960) in 1956 and whose early designs include the portable, “lipstick-red” Olivetti typewriter Valentine (1969).

It’s a story easy to romanticize—especially from the vantage point of the country’s current economic stagnation. Photographer Santi Caleca is one of the rare voices who lived through those years firsthand and can tell the story from the inside—without succumbing to easy nostalgia.

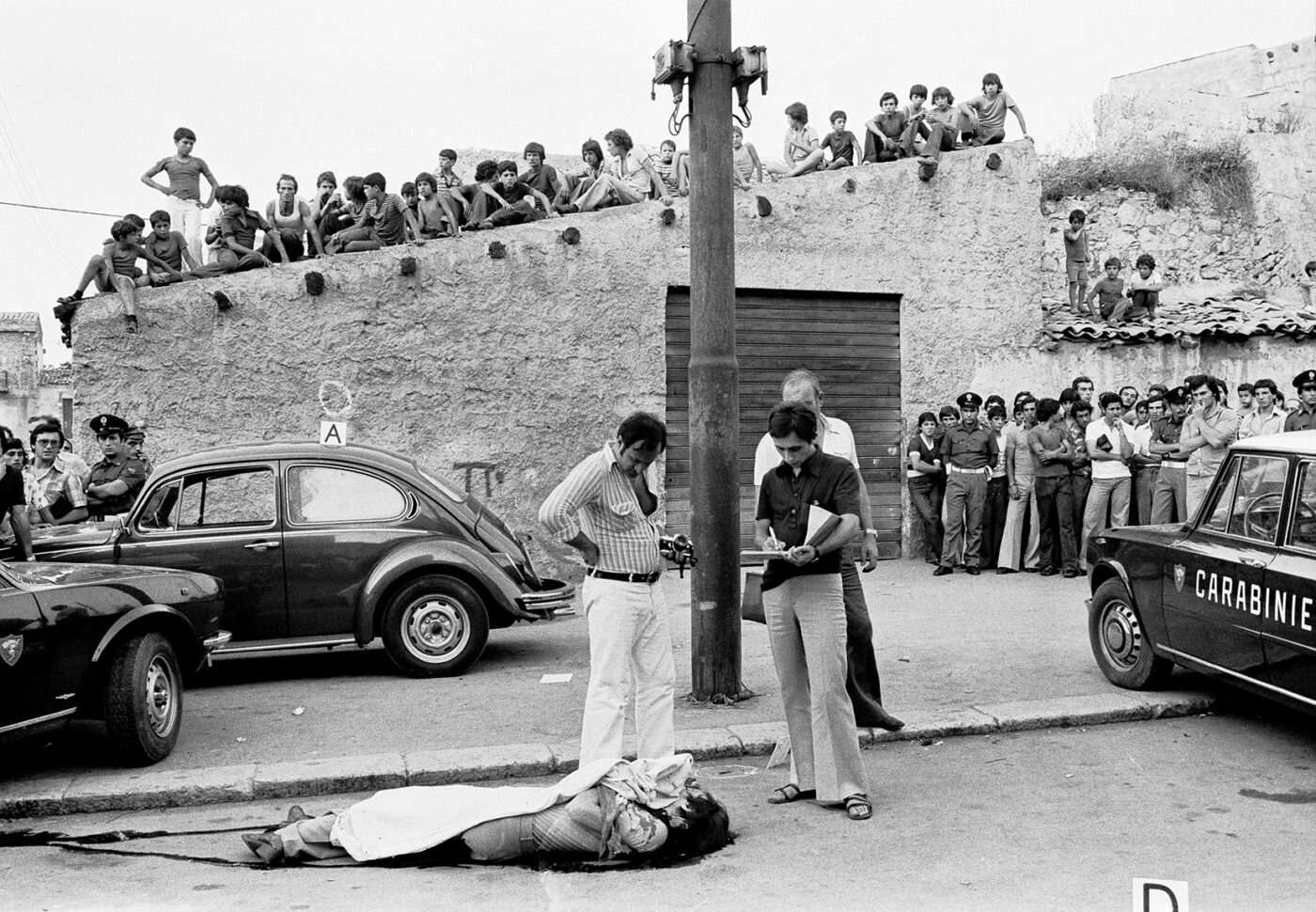

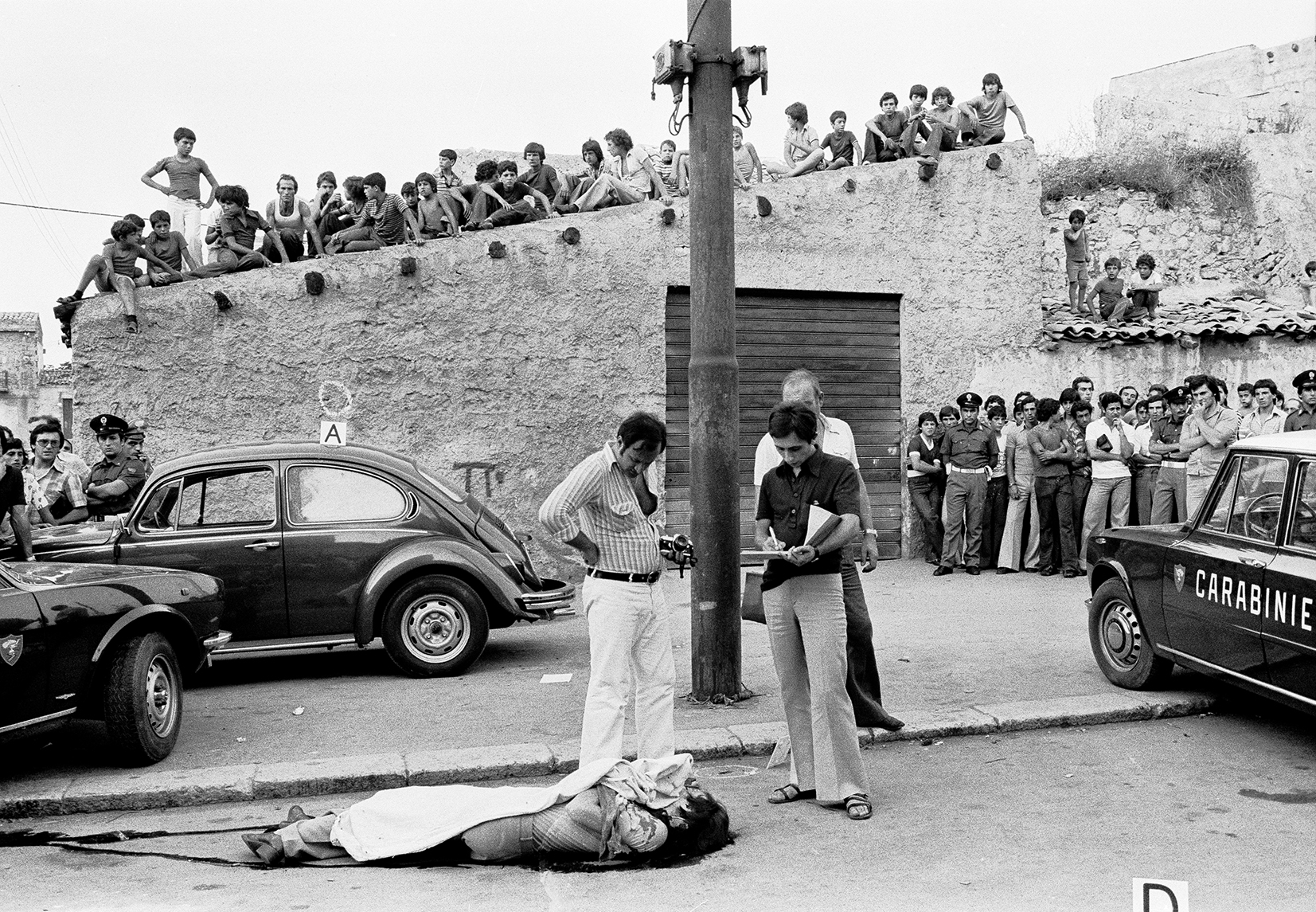

A murder in Palermo, 1976 (Santi used to cover mafia activity for the Palermitan left-wing daily L’Ora); Photo ©Santi Caleca

Born in 1947 in Palermo, Santi has lived many lives—first as a cash-strapped bohemian in 1960s Paris and Milan and later, as a photoreporter covering mafia killings for the Palermitan left-wing daily L’Ora. A chance encounter with Sottsass, exactly thirty years his senior, in 1977, as well as a collaboration with Casa Vogue, would instead steer him toward a career as a design photographer. He would not only work on the catalogs and campaigns of all the biggest Italian manufacturers—from Alessi, Flos, and B&B to Cassina and Cappellini—but also as a long-time friend and collaborator of Sottsass himself. The two of them worked on countless projects together, including the iconic architecture semiannual journal Terrazzo, and Caleca is probably the author of Sottsass’ most famous portraits, including the beautifully pensive snapshot that graces his autobiography Scritto di notte (Written at Night), first published by Adelphi in 1992.

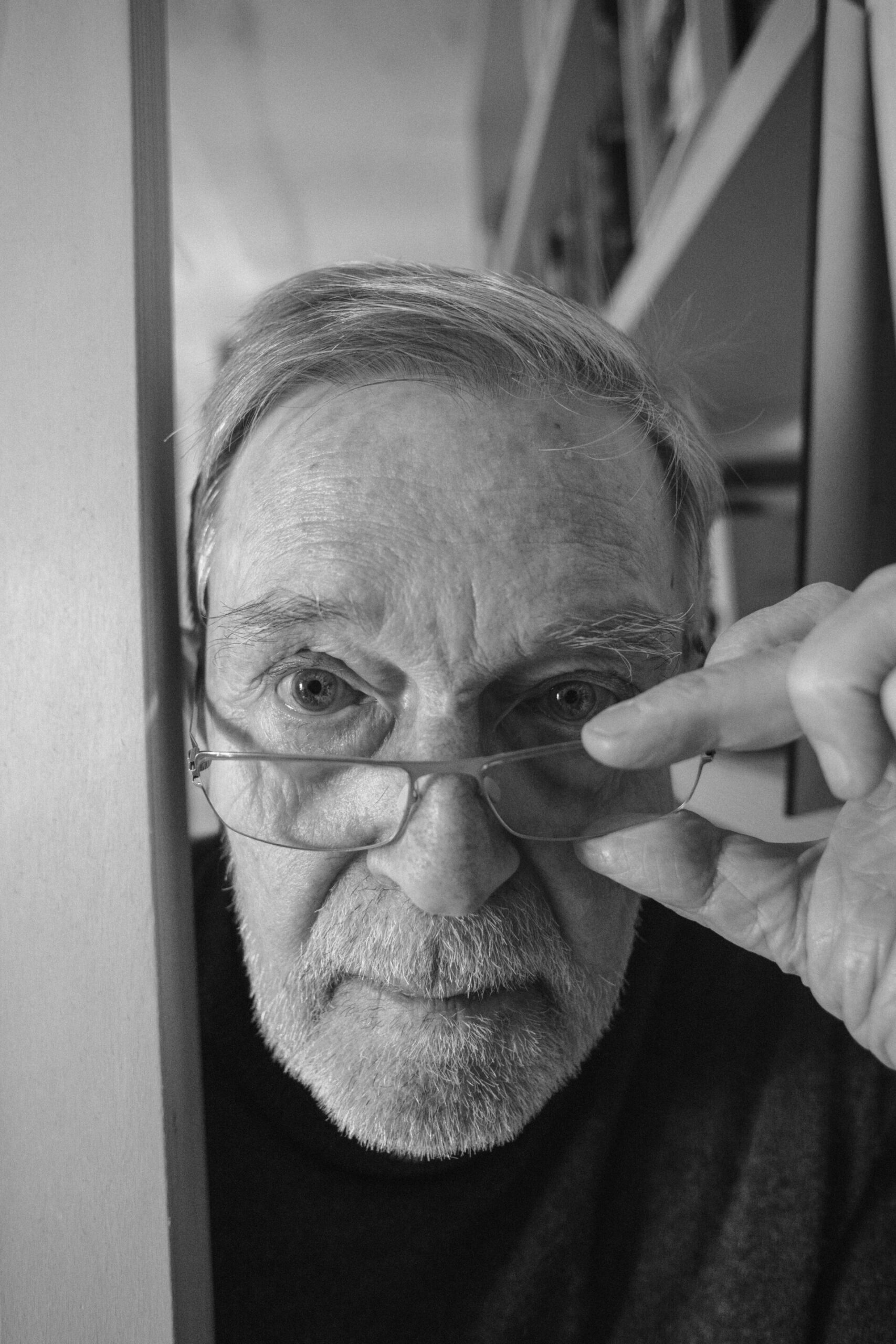

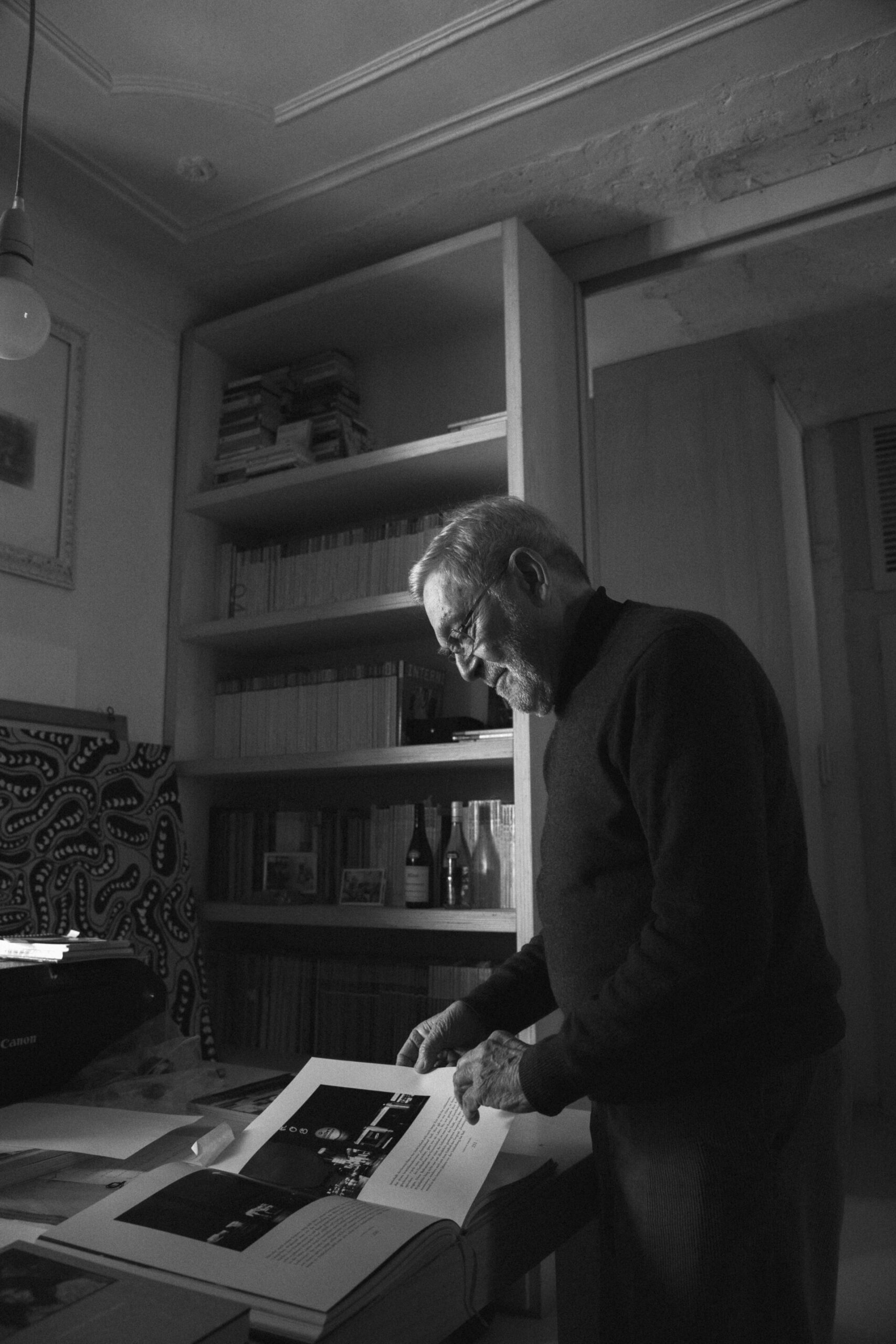

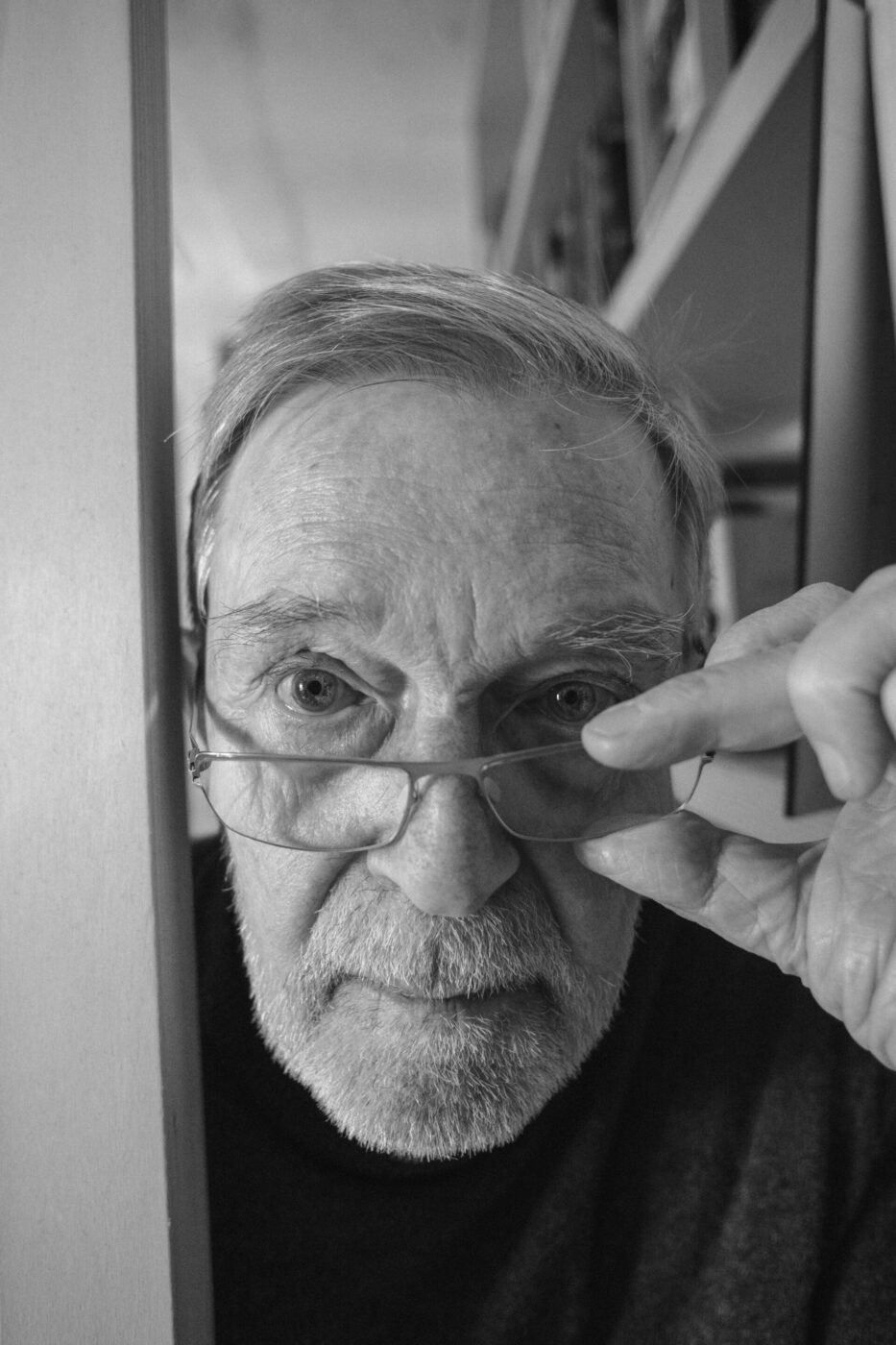

Santi Caleca at home; Photo by Tommaso Serra

When we visit the photographer in Milan, at his studio on Via Carlo Poma, on a chilly morning in mid-January, Santi (78) receives us on his own. His wife Aurora di Girolamo—also a photographer and a painter—has traveled to Palermo to take care of some family matters.

After a few civilities—during which his ironic, easy-going manner doesn’t take long to come out—he suggests we sit at his computer; he wants to show us the book he’s working on with art director and image consultant Roberto da Pozzo. As per pitch, we are after a history of Italian design through his photographs and memories, and an overview of his work in book form seems the perfect place to start. However, we soon understand he’s not interested in giving lectures or, worse, “mothball-smelling” tales of the good old days.

Rather than a straightforward history, the book is organized around a series of striking, often unexpected, resonances and juxtapositions. The incongruous shadow projected by Tom Dixon’s chaise longue Bird, an optical trick he came up with for Cappellini’s 1990 catalog, gives way to the impossible shape of an olive tree in Agrigento. Likewise, close-ups of spire-shaped pens designed by Aldo Rossi are soon followed by photos taken in a Thai massage parlor of Hannover’s Red Light District (which would later inspire a series of lights by designer Sergio Mannino). And, for the two mornings that we spend with him in his studio, the conversation takes similarly unpredictable directions—woven with anecdotes from a life lived seeking adventure, sharp observations on the state of the industry, and reflections on how design has evolved since his start in the early 1980s.

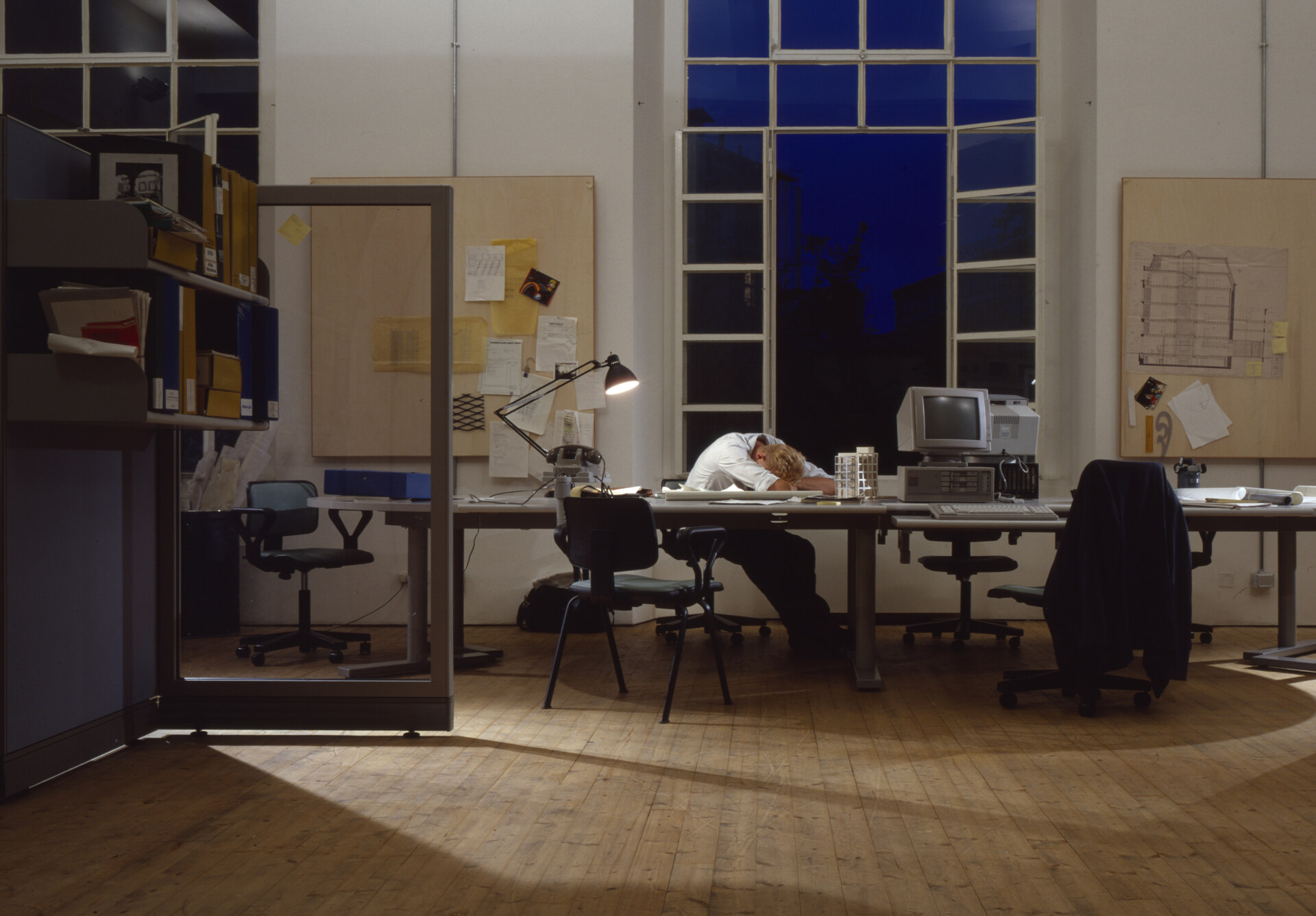

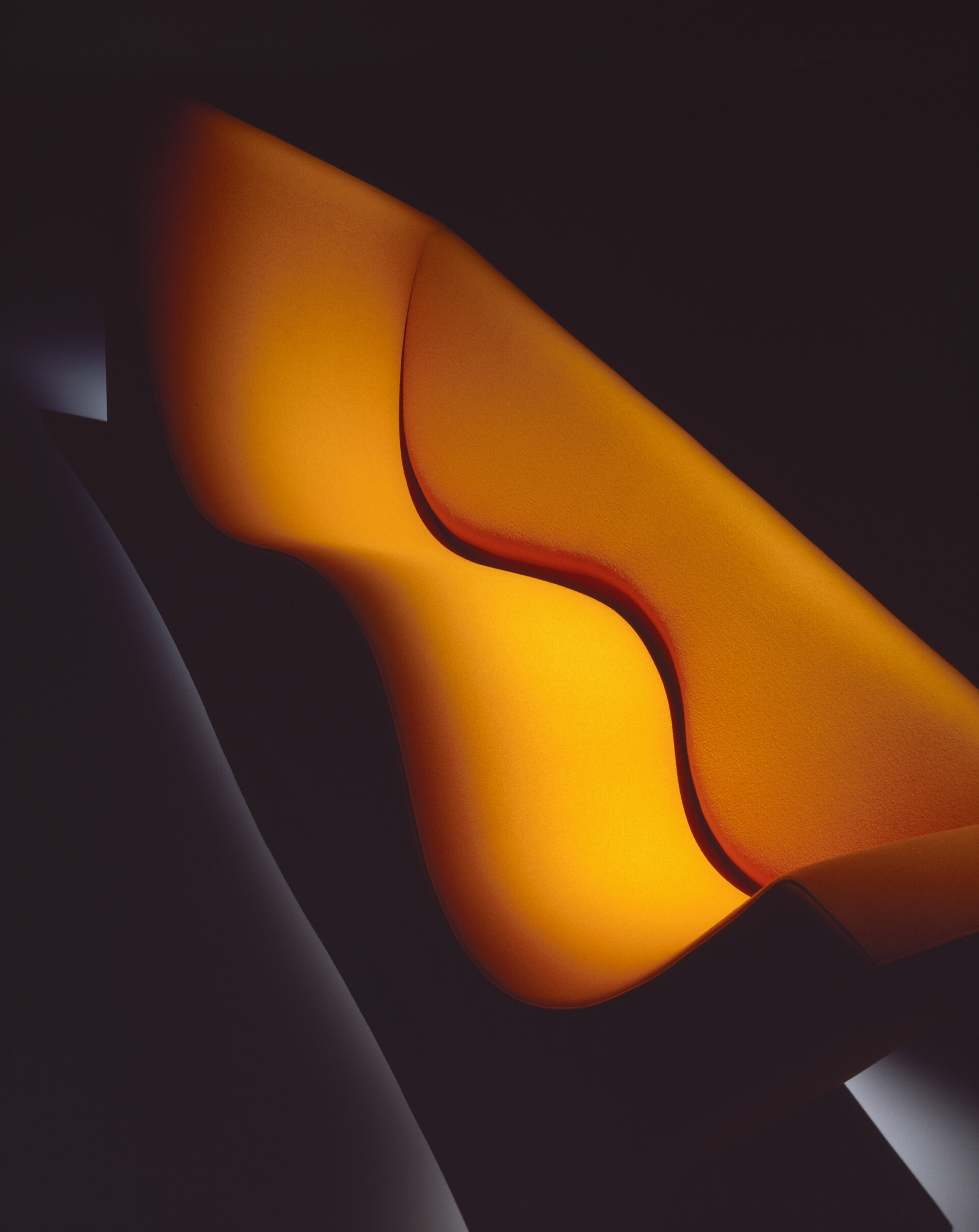

Photo for Olivetti Synthesis that also featured in Terrazzo Magazine; Photo ©Santi Caleca

Three Sofa de Luxe, designed by Jasper Morrison for the Cappellini; Photo ©Santi Caleca

“I had no patience for beautiful photos. I wanted to invent stories,” he says of his approach to still life, recalling his first Alessi assignment in 1980: shooting narrow strips (29 cm by 3 or 5 cm) for a catalog designed by Bruno Munari. And if his professional photos, taken with the help of an optical bench, betray a knack for geometry, perspective, and optical illusion, there are as many snapshots that rely on happy accidents: his taste for the unforeseen and incongruous is seen in the stocky figure of a mustached gardener peering in and disrupting the sleek, self-serious aesthetic of a modern Cappellini interior or the whimsical shot of an architect at Olivetti pretending to be fast asleep.

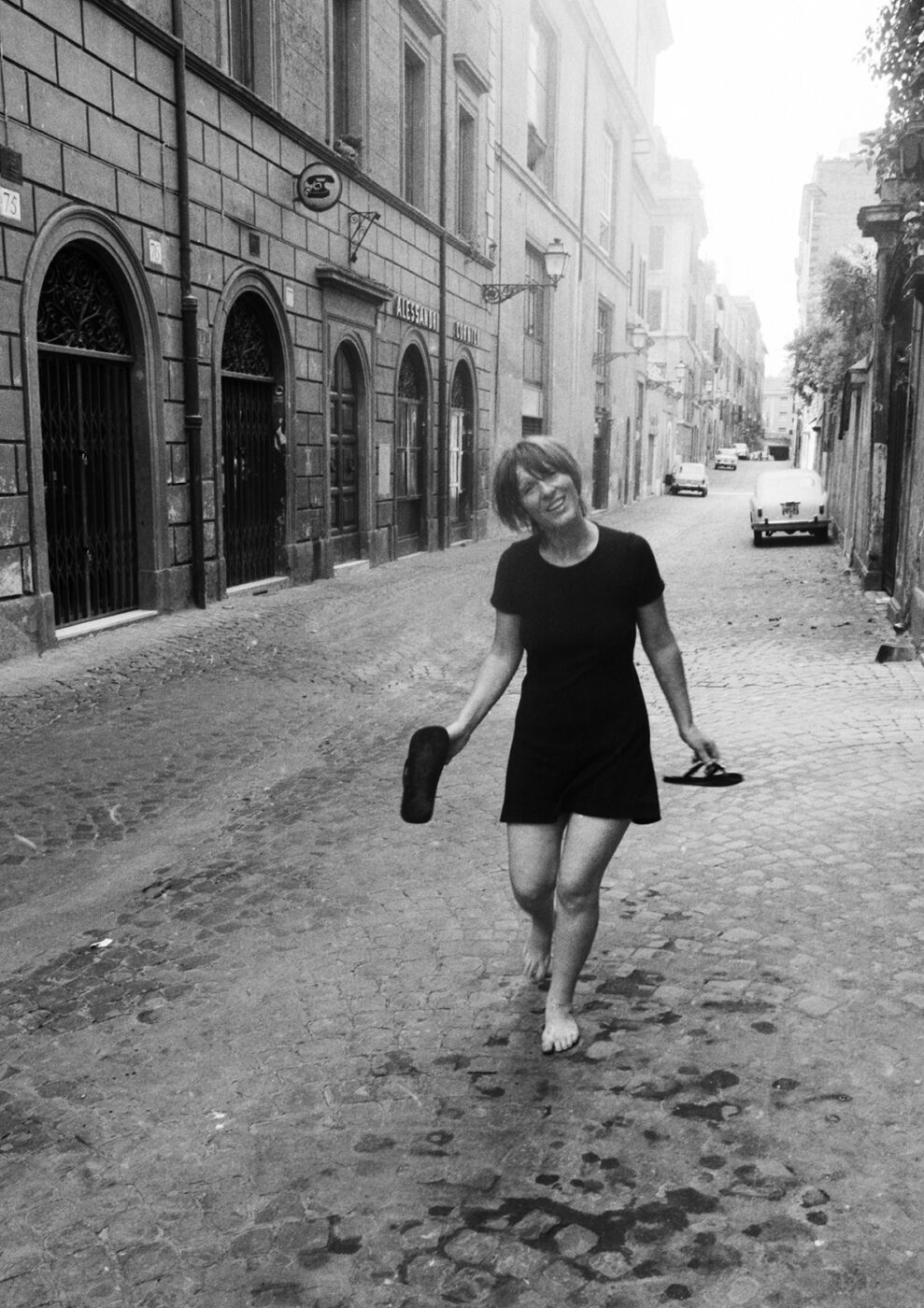

A picture of Milan in the late 1960s, and later of Villa Borromeo in Cassano d’Adda, are enough to make him backtrack to his early years. At the time, Santi and his then partner Letizia Battaglia (1935-2022)—who would become the leading photographer of and witness to Mafia violence in Palermo—were sharing a tiny apartment in Milan. “I have always felt a certain intolerance toward the idea of having a regular job,” Santi tells us. “One day, we woke up and I saw all those people in the freezing cold waiting for the tram to go to work… I thought, ‘I have to get out of here.’” At a friend’s suggestion, Santi and Letizia moved into the second floor of the opulent, aforementioned Villa Borromeo, on the Milanese outskirts.

Photographer Letizia Battaglia on Via Giulia (Rome), 1972; Photo ©Santi Caleca

In Cassano d’Adda, Santi and Letizia befriended their neighbor, Finnish designer and artist Liisi Beckmann (1924-2004). Santi shows us a black-and-white photo of a rustic interior from his book, pointing to a chair shaped in successive waves of undulating polyurethane foam. “That’s Liisi’s most famous chair,” he says—the Karelia easy chair. Designed in 1966, the toy-like piece spent years languishing in furniture company Zanotta’s archives, essentially forgotten. That is, until one of Santi’s photographs of Villa Borromeo sparked its unexpected rediscovery, leading to, first, a retrospective at Milan’s Triennale in 2017, curated by Marco Sammicheli, and later that same year, Zanotta’s reedition of the Karelia.

As we keep flicking through the book and Santi comments on pictures of slick interiors, breathtaking architectures, and sometimes less dreamy snapshots of Sicily (during his time at L’Ora, he photographed more than 60 killings, he tells us), our conversation drifts to the time that Santi, barely 20, had to abandon his car in front of the Operá in Paris. “At the time, Paris was the place to be”, he comments.

With a proud smile, he recounts how he and a friend drove the length of Italy without a valid license, only to be stopped at the French border when his friend tried to enter without a passport. Most would have turned back to Palermo, but they tried another pass instead. At 2 AM, the guards simply waved as they breezed through.

Once in Paris, Santi ran rapidly out of money and, rather cinematically, out of gas right in front of the Operá, where he left the car. By the time he scraped together the cash, it had been towed. “I just had to leave it,” he says, as retrieving it would have required a valid license.

His wild years also included brief stints in Italian jails—twice for driving without a license, once while on assignment in Calabria, and another time after insulting a cop who refused to let Battaglia through at a concert. “This time as well, I was saved by an amnesty,” he says, with a laugh. “And was able to walk out in July, just in time to go on holiday.”

When it’s time for lunch, Santi invites us to the Roman trattoria down the road, Nonna Maria, where we’re joined by his son Alvaro (31); Santi orders his specially-prepared aglio, olio, e peperoncino. After a coffee and brownie at a Davide Longoni bakery, we feel like we’ve gained his trust, and the following day, he invites us into his home.

Santi Caleca; Photo by Tommaso Serra

As he told us the day before, the studio and its movable panels were designed by Michele de Lucchi (b. 1951), one of Italy’s most famous archistars and a former member of the Memphis Group. Most of the furniture in the house, however, bears the unmistakable mark of Sottsass and his colorful syncretism.

Pointing to a totem-like cabinet, Santi recalls how furious Sottsass was when he dared visit Brugola, the carpenter in charge of making it, and suggested adding a hidden compartment. “He didn’t want to show it, but he was so pissed off,” Santi says, laughing.

Looking at these old pieces puts him in the mood to talk more about his career and, over another coffee, we finally deal with the subject of design head-on. He tells us about meeting Enzo Mari—a hero of ours, famous for his left-wing politics as well as his difficult character. “I was called to take a couple of portraits for an exhibition that Sottsass and [Mari] were doing together. We get everything ready, but he starts to look all gloomy and cross. At some point, he springs up out of the blue and starts shouting while pointing at a hammer & sickle [one of the tropes of his later work], ‘I am that, you understand?! I am that…’ I don’t know, he must have thought he looked vain for having his photo taken.”

He shows us portraits of Dino Gavina—the founder of iconic brands Flos and Paradisoterrestre, as well as a great designer in his own right—with whom Santi had a great friendship. When asked how things have changed since the 1980s, Santi cites Gavina as an example. What’s missing today, he says, are visionary entrepreneurs like Gavina and Alberto Alessi—people with vision who are willing to take risks. Many of the manufacturers that have made the history of Italian design—and whose showrooms dot Via Durini, not far from the Duomo—have merged to stay competitive in the global market and, as a result, have taken up a corporate style of management that Santi jokingly calls “la catena della paura” (“the chain of fear”).

He then shares a string of off-the-record anecdotes that illustrate his “rocky” relationship with marketing directors. But his frustration is best summed up by a rhetorical question he had asked us the day before: “Who is there for a young designer today? Who will take a gamble?”

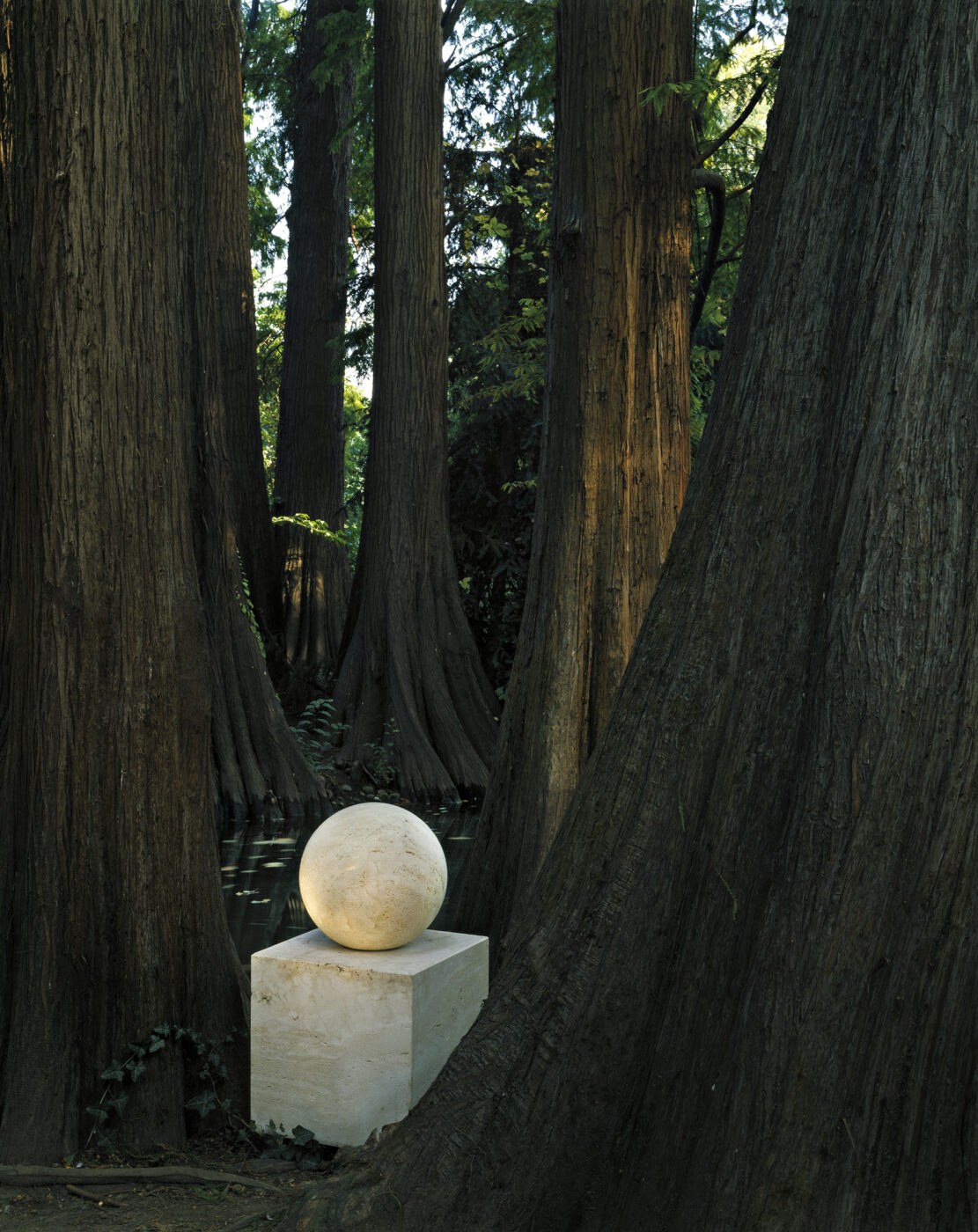

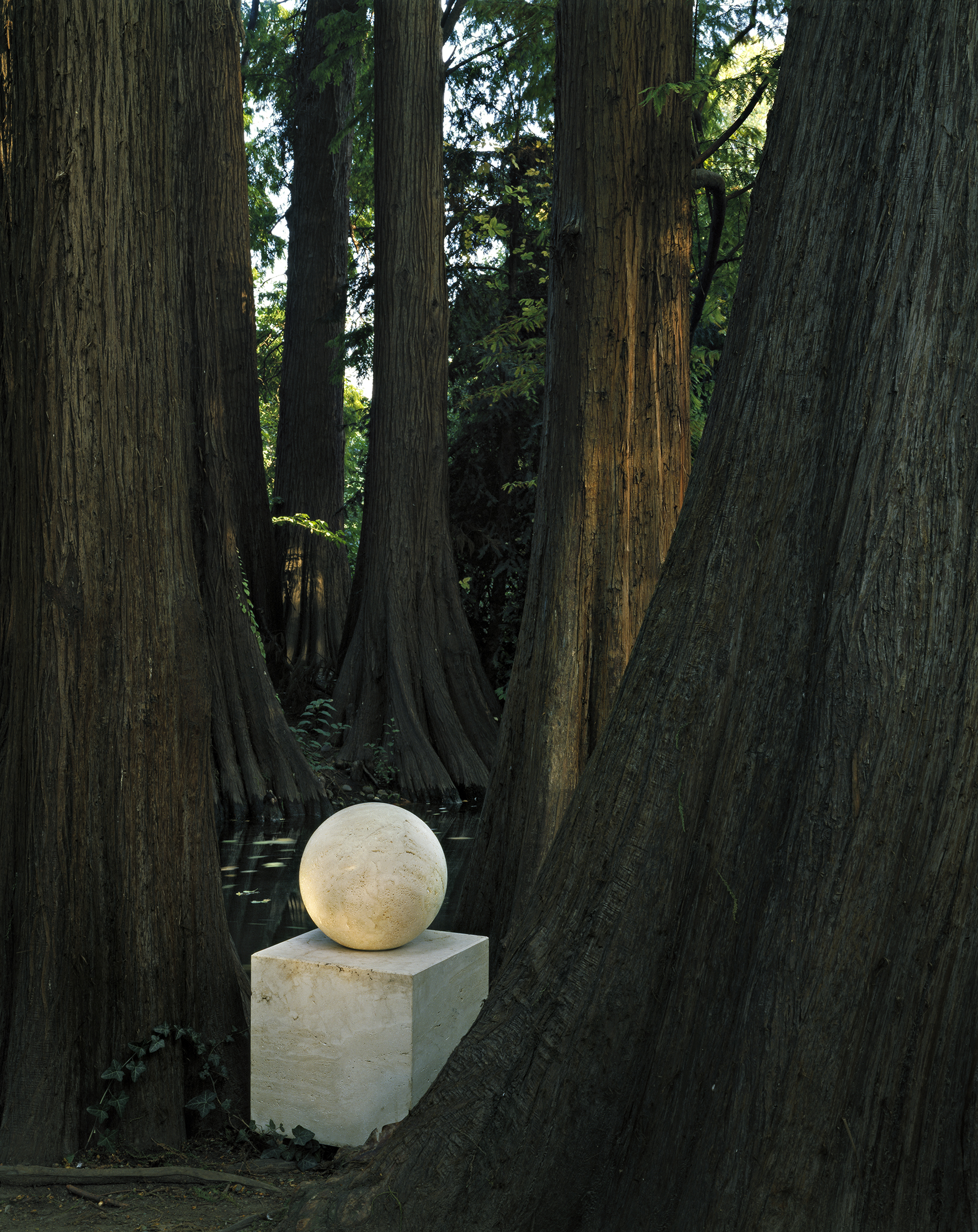

L'Altare della Buona Fortuna, a travertine marble homage to Wolfgang Goethe by Dino Gavina, (1983); Photo ©Santi Caleca

Sensing an opening, we are quick to ask him some more direct questions about Sottsass, Memphis, and his relationship with photography as well as design. He is quick to shut us down. People like to historicize, to attach cool labels, but the reality, Santi insists, is that the creative ferment all came down to friendship. “We were just ragazzi who would get together for dinner at this or that person’s house and stay together well into the night,” he says. Later, he distills the idea further: “Non epopea, ma condivisione di vita”—not some grand epic, but moments of life lived together. When it comes to photography and design, he repeatedly stresses he never cared too much about either; rather, work was always a means to an end, a way to chase experience. “It all came quite organically; I would get one project after the other, and I would fall in love with them each new time.”

Barbara Radice, Aurora di Girolamo, and Ettore Sottsass, and Santi's leg at dinner in Trapani; Photo ©Santi Caleca

To illustrate his point, Santi shows us a special issue of Terrazzo, the cult architecture and design magazine he conceived with Ettore Sottsass, Barbara Radice, Christoph Radl, and Anna Wagner and that ran biannually from 1988 to 1995. The edition, dedicated to cities, features two parallel photo-reportages he and Sottsass undertook while traveling the globe in opposite directions at the same time. Sottsass visited the likes of Brasilia and Buenos Aires, while Santi explored megacities like Cairo, Seoul, Tokyo, and Mumbai. The photos are striking—architectural, high-contrast—but once again, rather than reflecting on his craft, Santi prefers to recount how he managed to traverse half the globe and apply for an Indian visa without speaking a word of English.

The rest of the day passes by like this, between anecdotes of the time he was shipped to Hong Kong to photograph an Esprit store—the 1980s cult brand by Doug Tompkins (1943-2015), also the founder of North Face—and an impromptu ping pong match.

Over another lunch at Nonna Maria—he must be a regular, judging by the jokes he cracks with the owner and the waiters—he tells us about his life’s biggest regret. During his time in Paris, he was given a once-in-a-lifetime chance to meet Man Ray (1890–1976). “It was all set; I showed up at the appointment at the agreed moment, but at the last moment, I chickened out.” He can’t quite explain why. Instead, he wandered into an alley and struck up a conversation with another fellow artist. Only later would he find out that the odd-looking man he had spoken with for the better part of an hour was none other than Brassaï (1899–1984).