Situated midway between Africa and Europe, Sicily is an island of extremes. Earthquake tremors, incandescent volcanos, and three sparkling seas vie for supremacy over its rugged terrain, a testament to the indomitable force of nature and our impotence in its shadow. Look beyond Sicily’s staggering landscape, look closer, and you’ll come across a more modest–but equally extraordinary–form of beauty. Its allure lies in its understated simplicity, and the images of Sicilian photographer Leandro Colantoni might just help you find it.

By skillfully combining light, geometry, and colour, Colantoni’s photographs take us on a sun-drenched journey where even the most mundane moments invite us to revel in the richness of life. With a refined and dreamlike quality that borders on the surreal, his emotive images observe the minutiae of the everyday, providing a window into the soul of his native land’s diverse culture and landscape. But perhaps the real reason 32-year-old Colantoni has garnered such a significant following over the past few years is his unique ability to capture a visceral Italian nostalgia with a distinctly cinematic feel. His images remind us that a whole world of ordinary joy exists to be discovered, if we’re willing to look close enough.

I ask the Agrigento native how he first discovered photography and am surprised to learn that it wasn’t until 2016 that he first picked up a camera. Before then, the self-taught photographer worked primarily in the realm of graphic design, which at least partially explains his uncanny eye when it comes to composition.

“I dislike categories. Photography should be universal; it should embrace everything and speak a language that is understandable to everyone,” he explains. “I’m interested in the simple things, the quotidian, and most of my images are born out of instinct. First and foremost, I want to document my home, the land I was born and raised in,” he continues. “My aim is to depict the reality that surrounds me: our people, our way of life… let’s call it Sicilianità, or ‘Sicilianness.’ I try to portray the ordinary things, the things we encounter everyday but too often take for granted. I intentionally steer clear of more profound, complex themes. This way, my photography reaches everyone.”

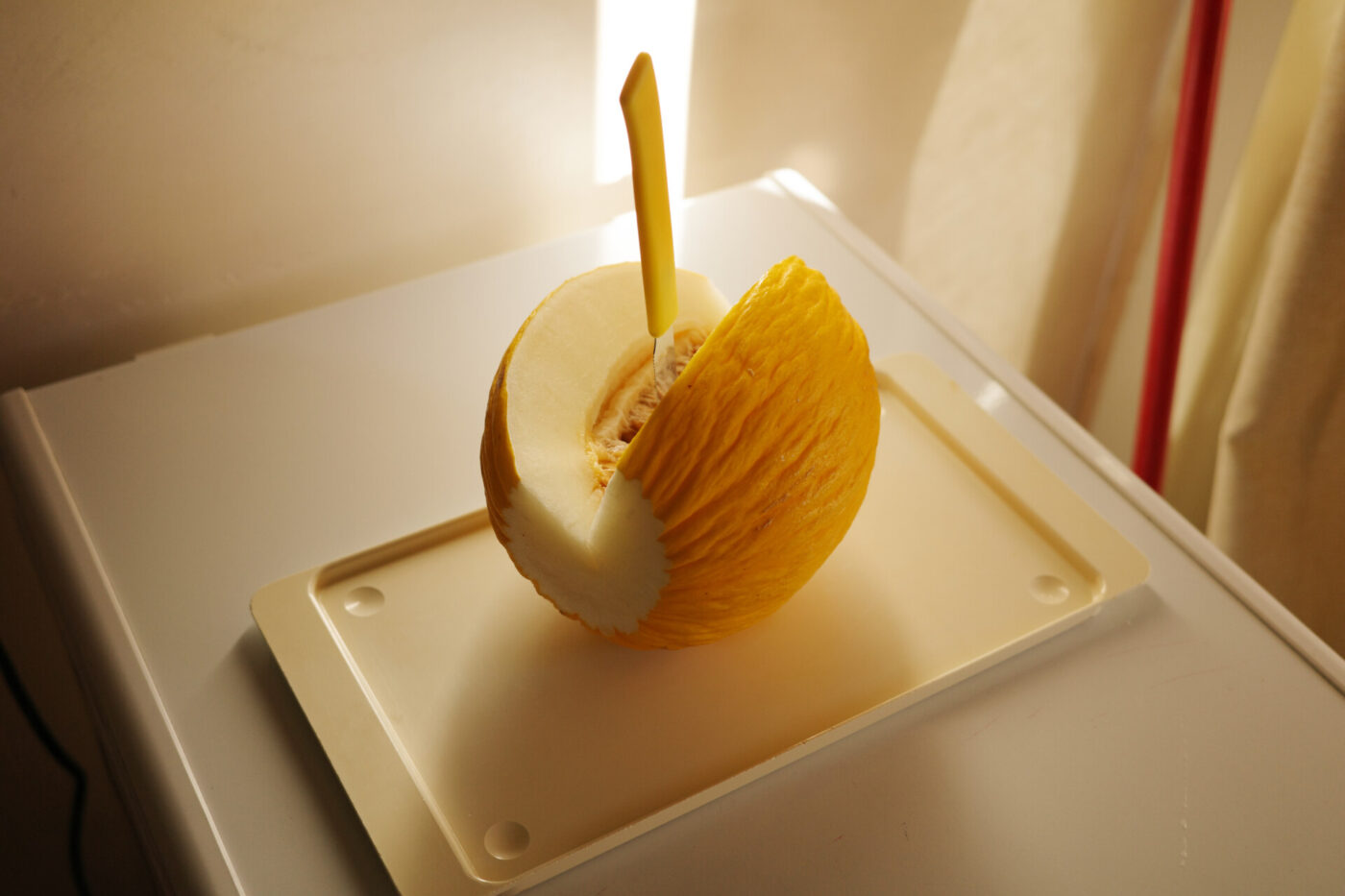

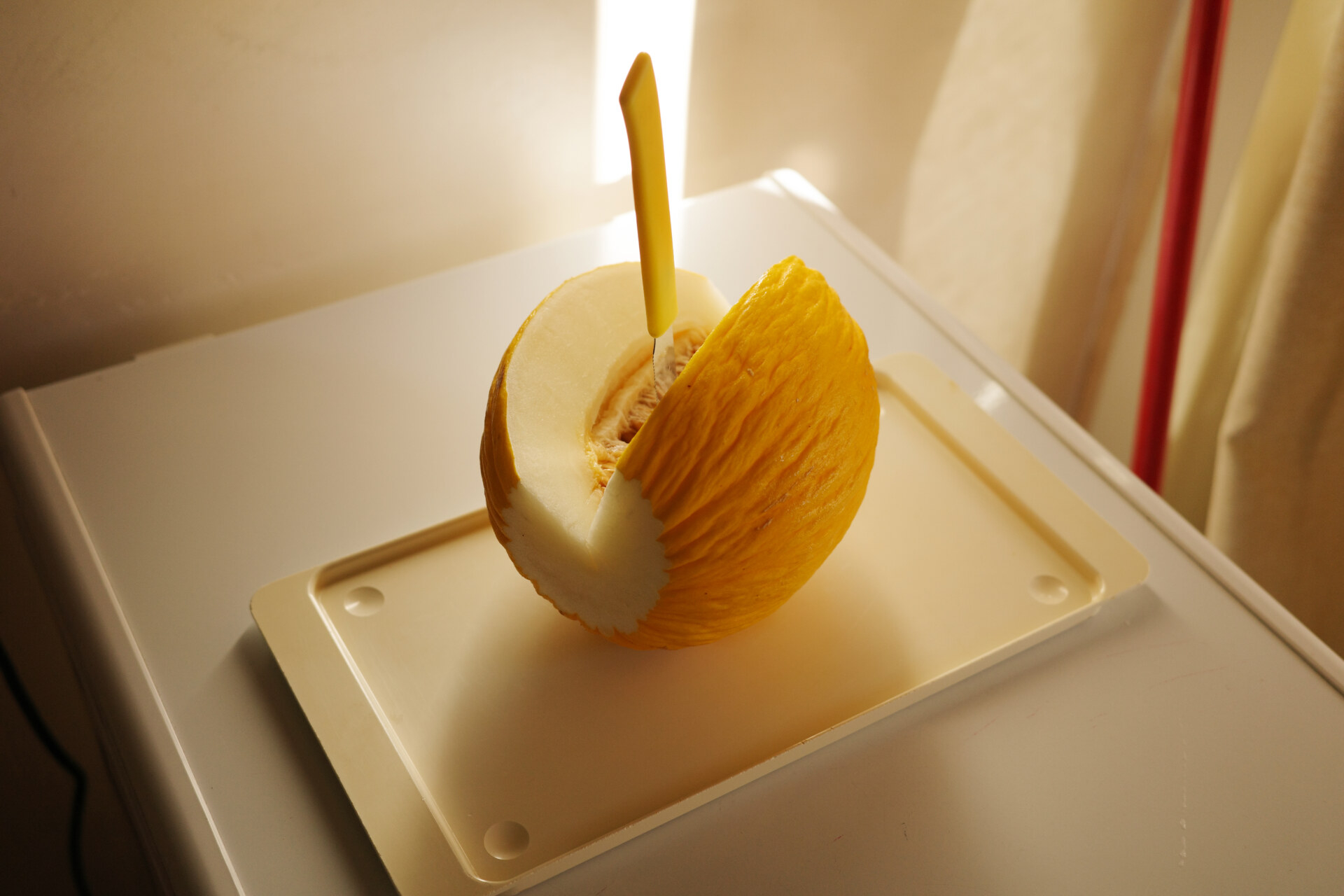

Colantoni’s response to my question is unusually refreshing to hear; it’s not often that an artist sets out to decontexualise their work, rather than the other way around. But despite the photographer’s unpretentious approach to image-making, there’s an undeniable depth to his work, one that reveals an innate ability to recognise moments of fleeting, contemplative beauty. His crisp shots feature recurring motifs such as plump citrus fruits, religious trinkets, beach towels, and Mediterranean scrub–but what unites all of his subject matter is an understated stillness that is both profoundly melancholic and quintessentially Sicilian.

In one image, Colantoni captures the unassuming beauty of a yet-to-open gelato and granita kiosk. Brightly lit by the morning sun, the shadows of a nearby olive tree create intricate patterns on its yellow façade. It is a straightforward, uncomplicated photograph–yet I can’t help but feel an overwhelming sense of longing while looking at it. For a split second, I am transported to the balmy Mediterranean, and vivid memories of all the 4 PM gelatos of my childhood suddenly flood my consciousness. I am brought back to every moment I have waited impatiently for my turn at an ice cream stand just like this one, a glistening 2 euro coin in my palm, my still-wet hair forming a cool water trail down my back, the singing of the cicadas so deafening it persists in my dreams. This image allows me to be in two places at once, and that is no small feat. From my kitchen table at my London home, I inhale the scent of salty sea air, taste that first blissful lick of creamy green pistachio–and hear myself sigh once the feeling passes.

In another photograph, Colantoni has zoomed in on what appears to be the surface of an ancient wall or pillar, its rough texture weathered by centuries of sun, wind, and rain. Immediately noticeable amidst the countless lines and grooves that have accumulated on the wall’s surface is a faint scribble in permanent marker, perhaps left behind by a visitor unable to resist leaving their mark on history in some whimsy, inconsequential way. Despite the fact that the faded word is barely legible, the scribble is testament to the passage of time, serving as a small but meaningful reminder of the continuity of human connection.

I proceed to ask Colantoni about his influences, and the first person that comes up is none other than Luigi Ghirri, the prolific Italian photographer and writer whose acclaimed work famously blurred the line between fiction and reality. “Discovering Ghirri’s photos and texts definitely pointed me in a certain direction–I became mesmerised by the dreamlike quality of his work,” he tells me. “The greats of American colour photography such as Eggleston and Shore, to name a few, have also had a huge impact on my practice. But something that continues to fascinate me and that I’m trying to understand in more depth is the common need of Sicilian artists–from music to literature–to tell the story of this land through their work. This is the same need that has driven artists like Franco Battiato and Carmen Consoli to write songs in Sicilian dialect, and it’s what I’m trying to uncover through my photographs.”

I urge the photographer to elaborate, and he tells me that sometimes he feels envious of the thousands of tourists that flock to his home, fascinated by a romanticised version of Sicily that continues to be largely misunderstood. “I was born and raised here, so I’m curious to see how tourists see my land. Everyday, I pass the Valle dei Templi–one of the most visited archeological examples of ancient Greek art and architecture–on my way to work. This is my normality. Perhaps this means that as Sicilians we have become partially immune to beauty. We’ve grown accustomed to it and in turn, we take its splendour for granted.”

If this is the case, I ask, then what exactly does Sicily mean to him? “I wish I had a straightforward answer to that question,” he responds. “I often ask myself the same thing. Despite what I’ve just said, I feel that I’ve developed a love for Sicily that goes hand in hand with my practice. Photography has allowed me to get to know it better, and to appreciate the particularity of Sicilians as a people. Prior to discovering the medium, my relationship with Sicily was a lot more ambiguous–I would go as far as to say it was a bit of a love/hate one. I’d like to think that the love has now taken over.” I don’t disagree: all of Colantoni’s images reveal a tenderness, or some form of secrecy, that we are only allowed a momentary glimpse of.

The day after our conversation, Colantoni emails me a selection of photographs he’s taken over the past year. As I flick through them on my laptop, I am once again overcome by the same longing I felt when I came across one of his images for the very first time. For what feels like the hundredth time this week, I hear the light, rhythmic pitter-patter of London rain. For once, its persistence doesn’t faze me. In my mind, I’m still queuing for gelato under the scorching afternoon sun to the sound of the cicada’s buzzing symphony.