“Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is an absurd one,” reads the beginning of Dimitri D’ippolito’s bio–a Voltaire quote that sums up the 31-year-old photographer’s practice well. Throughout his work, the eye-catching appears uncanny; beauty and danger circle each other. A night scene by the sea contains two silhouettes, one suspended in mid air. An embrace toes the line between innocent and sexually charged. The elegant white-collar workers of the City of London, who may or may not be complicit in money-laundering for the Italian mob, are faceless, a stark reminder that this dirty money permeates everything. The beautiful landscapes and people of the Bagnoli neighborhood of Naples are set against the looming backdrop of the abandoned metallurgic plant which haunts the area. Contrast is a word that comes to mind, dreamy is another, both in regards to the oneiric Italian topography and in his employment of film grain, as opposed to the digital pixel, which he finds “fluid, like water.”

Mare Chiaro, Naples

Mare Chiaro, Naples

His first camera was a gift from his uncle, in honor of his first communion. “That summer we went to Calabria. My father bought me three rolls of film, and I spent three days photographing just flowers. My father told me he wouldn’t buy me any more film if I was just going to photograph flowers.” This momentarily discouraged the young Dimitri, who took an extended break from this hobby until he came upon a small digital camera in high school: “I just used it to photograph my friends. I was a bit of a delinquent at the time; I was driving my mother crazy.” Jumping on his newfound interest in order to give Dimitri some direction, she called his grandfather who put him to work at SACI (Studio Arts College International), where he assisted Romeo Diloreto in the dark room, a fine art printer for Fratelli Alinari Archives and Elle Magazine. “Romeo is my master, he made me fall in love with this medium, this process, creating an image and thinking about what I could do with it, print it, create a narrative. I found something with which to channel my hyperactivity in a positive way.” He had thought before that he would study biology, but instead decided to go to Brighton University to pursue photography. “There, I was illuminated when my professor Xavier Ribas told me, ‘Images and words are interchangeable.’ It’s a game, a handshake between the two parts.”

A “handshake between two parts” could just as easily describe the photographer’s identity. Though a Florence native, Dimitri’s roots trace back to Calabria and the United States, and his first language was not Italian, but English. “I had a way of growing up and seeing the world that was not only Italian. Every year we went to the United States, and, as a child, I appeared more American than I am now, in the way I dressed and in the way I related–something that the other children never held back in making me notice,” Dimitri tells me. But 11 years abroad brought a sense of longing, and he started to identify with his native country in a way he hadn’t before. Of his time abroad, Dimitri notes that it forced him “to rediscover an Italianness.”

Amalfi Coast

Siracusa, Sicily

“I was finally able to embrace those parts of me that previously I struggled to recognise,” he continues. This is clear in his photographs today, which reveal an infatuation with the warm Italian light, its long shadows and chiaroscuro, with the country’s dreamy waterscapes, with the quirks of daily Italian life. Dimitri points to the familiarity of the culture and country, how he can shoot in a place where he is able to integrate himself seamlessly, following instincts without overthinking and, sometimes, putting the camera down to focus on what doesn’t belong on film or pixel.

But despite his fascination with Italy, Dimitri chose to stay in the UK, where he felt he had more work opportunities than in his native country–a sentiment shared by many of his age bracket. “The United Kingdom has given me the tools to think critically about my art. The UK is my workshop; Italy is a big playground. Our way of living life is very poetic. We are redundant. Here in the UK, they always want to get straight to the point–but I like to indulge.”

Ortigia Sound afterparty

Amalfi Coast

Though there’s at least one way in which the UK indulged him, for his love of music and the club scene took off there. Applying his visual practice to this world, Dimitri has, year after year, covered the Ortigia Sound System festival in Siracusa, Sicily. Photos of bodies swaying to the music, frozen mid-movement, are contrasted with elysian images of people enjoying a granita by the beach. His approach attempts to capture the sensory experience of being at the festival, not only through the music, but through the natural beauty of the Sicilian coast and its culinary canon, finding an allegorical parallel here through forms of escapism: “Eating and music are both forms of sharing, of going back to our purest, animalistic form of just feeling, a primordial state. At that moment everything else stays still.”

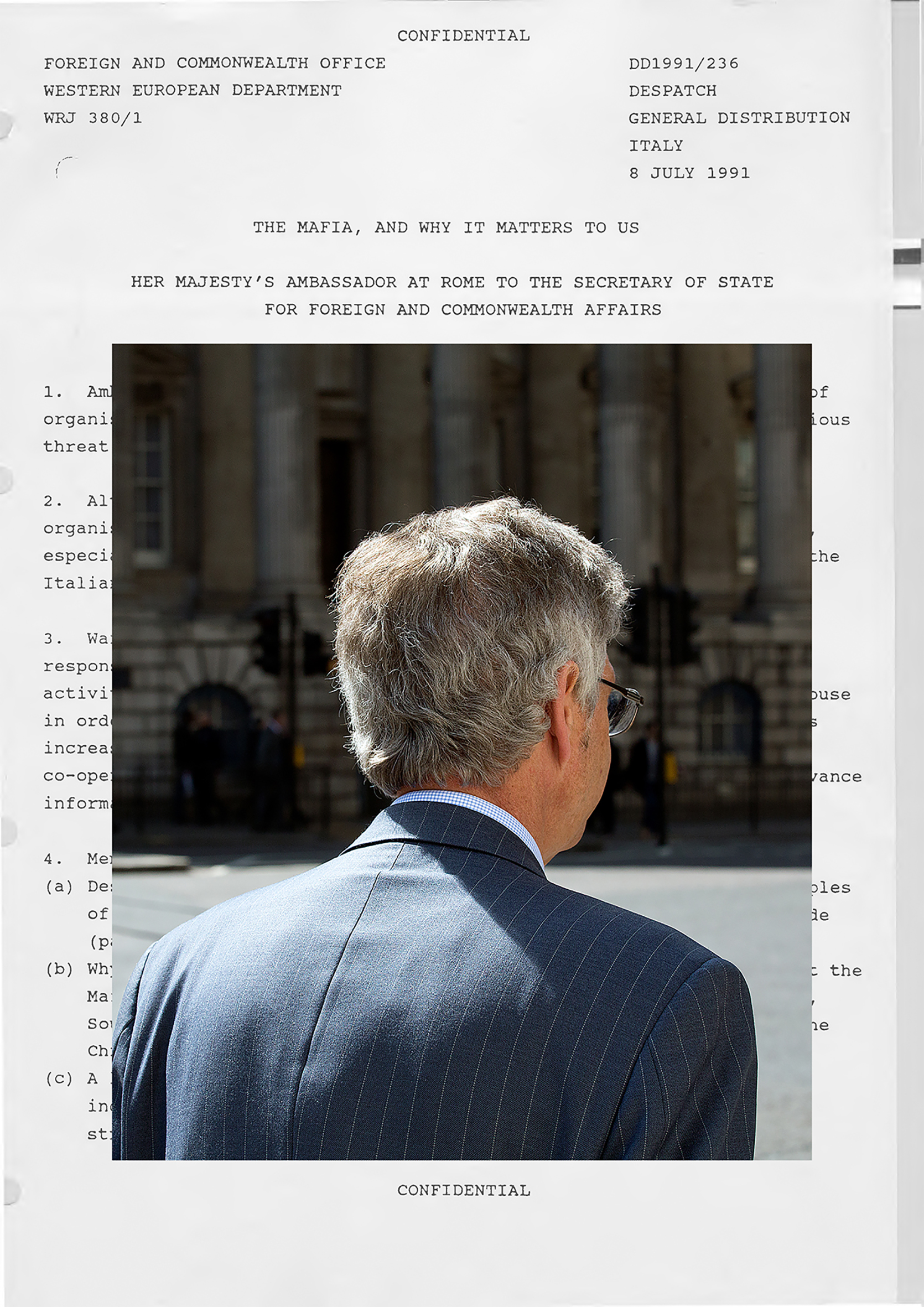

But it’s not just the paradisiac Italy that appeals to Dimitri, who also takes a keen interest in the country’s criminal underbelly. His project “They are not (yet)” aims to shine a light on the ever-presence of dirty money from Italian organized crime in the British financial system, in which it is invested and laundered. The project’s name comes from a quote by Francesco Forgione, the former head of the Antimafia Commission, who said, in reference to the rise of this phenomenon in 2009: “They are not killing in London yet, they are just investing.”

It’s a challenge to photograph an invisible crime–one perpetrated via computers, contracts, and handshakes–but Dimitri tackles it with obscured portraits of half faces and turned backs. “You feel a sense of uncanniness, the presence of this corruption.” Dimitri explains that there’s proof that Italy’s dirty money makes it into the economy of the city, but it’s difficult to pinpoint who’s investing it–especially when those investing it may not even know the origin of the money themselves. “My work here is a suggestion, a stereotype. I love stereotypes because, while they may or may not have a basis in reality, they are a universal language. But mostly I love to subvert them. In this case the question becomes ‘who is more dangerous?’ A tattooed thug throwing rocks at car windows? Or a white collar worker, who shifts billions of dollars, deciding the social and political assets of entire countries, or bankrupts a company leaving thousands out of a job?”

“They are not (yet)”

Subverting stereotypes is a theme he brings back to Italy too–particularly salient in one of the most stereotyped countries in the world. And while Dimitri tells me that his time abroad has allowed him “to take the most positive parts from both sides of [his] identity,” I’d argue that he’s not shy with the negative parts either. No subject matter is too heavy nor too light for his lens. He finds hope in the ruins of failed reclamation projects in Bagnoli, loneliness among the crowds of a music festival, moments of daily life that, at first beat, are beautiful and, at second, unsettling. The result is a portfolio that reads as a deeply veracious portrait of what it means to be Italian.

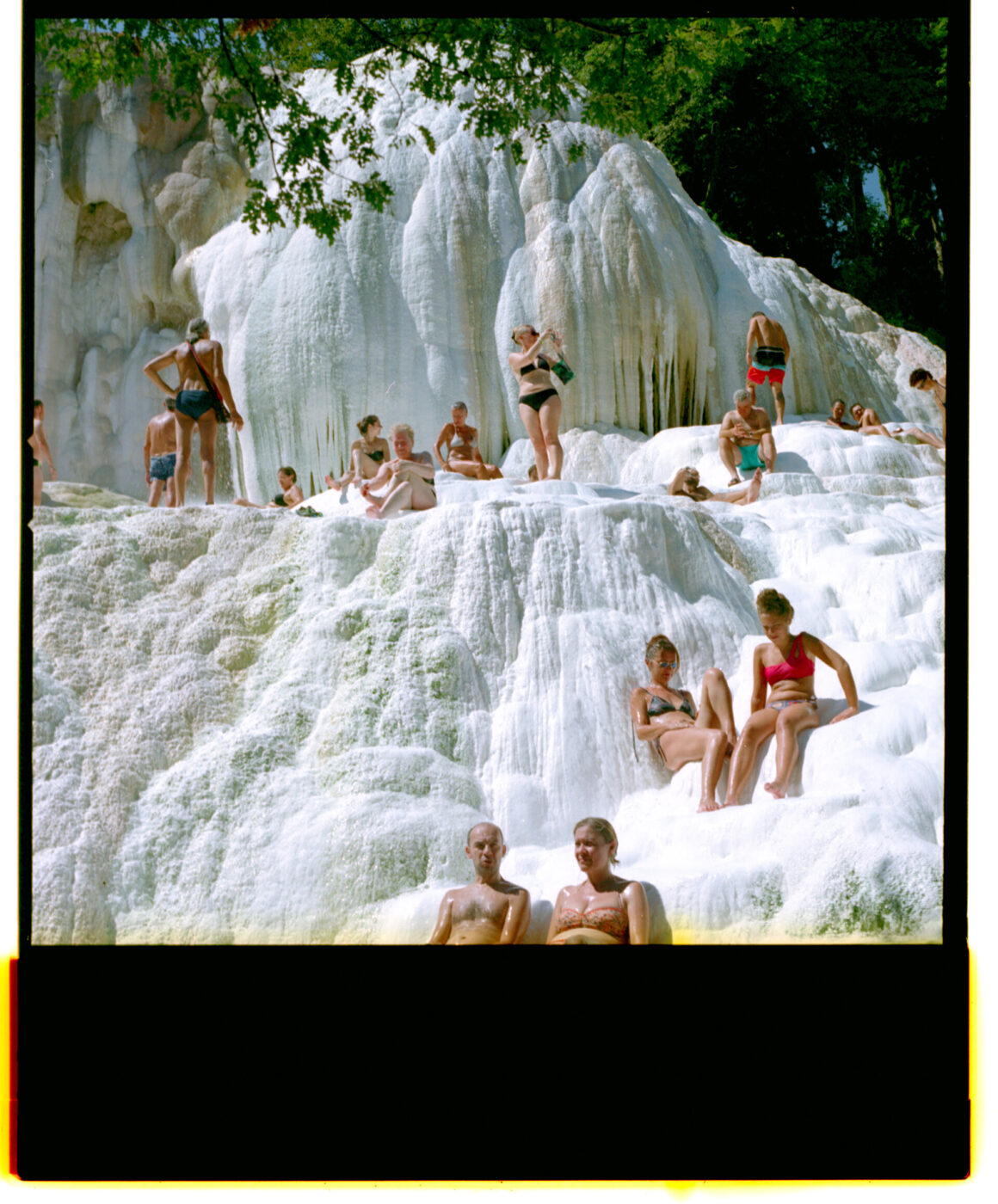

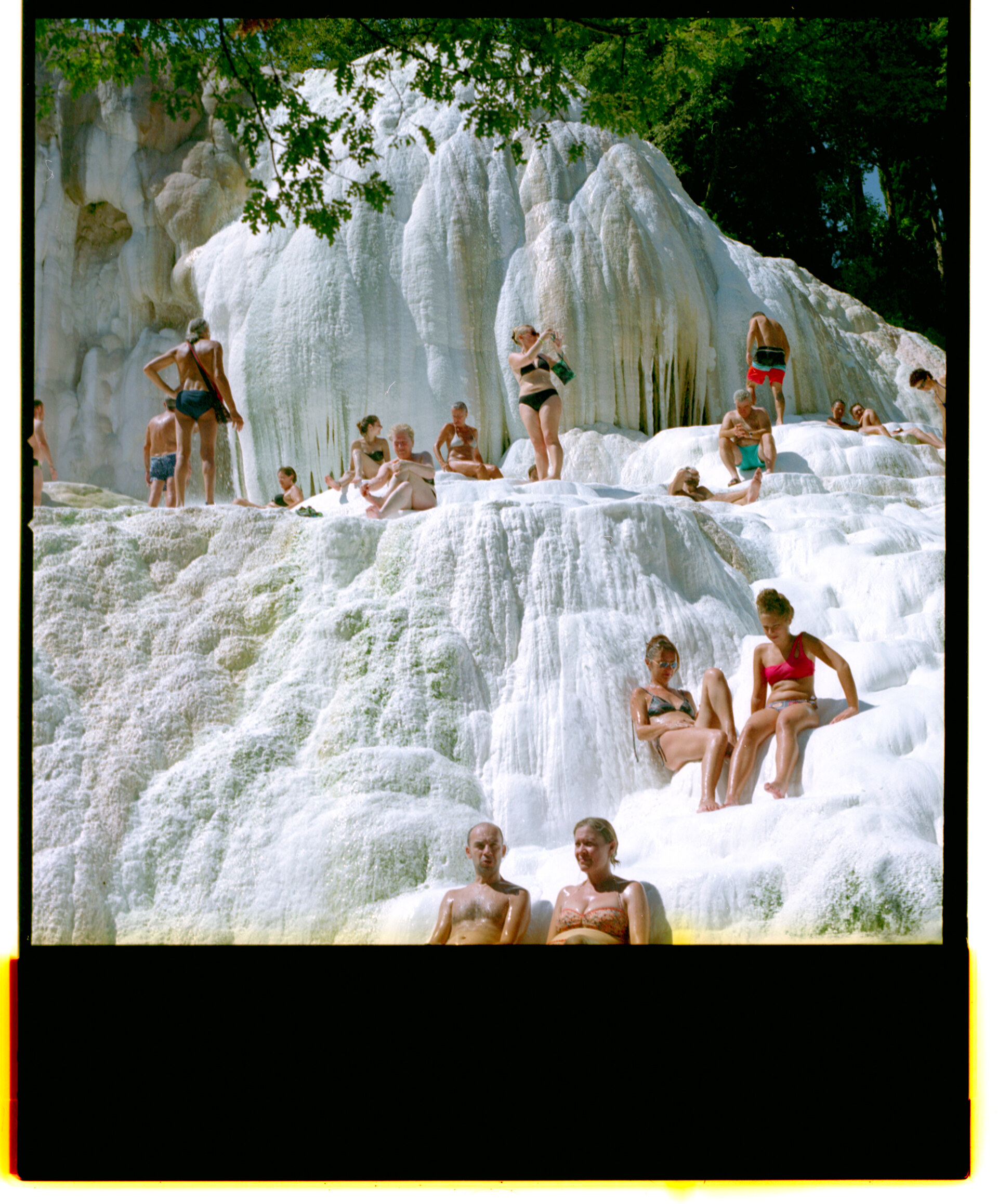

Bagni San Filippo, Tuscany

Parco Fluviale dell'Elsa