It’s Carnevale, the late winter festival season that beckons spring’s renewal. Snow is falling gently in Alessandria del Carretto, a town of stone buildings high in the Pollino mountains of Calabria. The lively drones of zampogna bagpipes and the crisp ones of tamburello frame drums echo through the narrow streets of the village.

Pugliese photographer Cosimo Pastore has traveled from his home in the province of Taranto to a mountainous area of Italy’s toe near the border of Basilicata, and though he’s no stranger to the colorful world of local traditions in Southern Italy, he’s surprised to find himself in a festival so alive.

Here, the Połëcënellë—Alessandria del Carretto’s historic Carnevale mask in two variations: Biellë e Brut’ (Beautiful and Ugly)—take over the streets, in a rite that alludes to a cathartic struggle between order and disorder, winter and spring. Identified by their wooden faces and ribboned crowns, each carries an heirloom pom-pom-tipped baton called a scriazzo as they move in a dancing procession through the village.

As he witnesses this unfolding, Cosimo feels the tap of a masked man’s scriazzo, first on his shoulder, and then on his camera.

“That day, something fell into place. I clearly felt I was in the right place,” Cosimo tells me. “And from there I never stopped. Analog_trad was born.”

I Polëcënëllë Biëllë, Alessandria del Carretto (CS), Calabria, Italia - Mamiya 645 _ Kodak Portra 400 VC (expired)

Madonna delle Galline, Pagani (SA), Campania, Italia - Fujifilm X-T4

His Analog_trad project is dedicated to recording “popolari” traditions like this one: religious processions, festivals from ancient calendars, and ancestral ways of working the land. He’s created a photo archive of these celebrations, primarily in Southern Italy and working exclusively with film, as well as a quarterly magazine in collaboration with graphic designer Miriana Liberti. Alongside his photographs, Cosimo makes field recordings—transhumance songs, processional chants, and more—to build living soundscapes.

Cosimo’s project has carried him across Southern Italy, documenting village rites: from Pagani’s Madonna delle Galline, where courtyard toselli altars open and devotees bring hens, eggs, and rustic dishes to the Madonna; to Montescaglioso’s Festa di San Rocco, where dozens of mounted riders precede a decorated Carro Trionfale drawn by seven horses; and even the December transhumance of Podolica cattle along the Tito–Tolve tratturi in Basilicata. In the South, where devotional calendars still shape civic life and pockets of pastoral culture endure, these practices remain a way of understanding “the heart of a people’s identity,” as Cosimo puts it. His photography invokes the pace and quality of presence that is perhaps characteristic of these old ways themselves.

Festa di Sant’Antonio Abate, Novoli (LE), Puglia, Italia - Leica R4 _ Ilford FP4 plus

Festa della Pita, Alessandria del Carretto (CS), Calabria, Italia - Leica M6 _ Kodak T-Max 400

Cosimo has been familiar with rites like these since he was young. “My grandfather Angelo used to take me to prepare the statues for the Mysteries for the Good Friday procession,” he recalls. “Listening to the funeral marches that accompanied these rites allowed me to immerse myself in a magical world that I probably didn’t fully understand, but that already fascinated me deeply.” As a child, Cosimo has played traditional music in his community and in organized groups, and today collaborates with musicians across Southern Italy. The omnipresence of music led him to see tradition as “something alive and experienced, more than a simple academic or artistic interest.”

“While music has allowed me to explore cultural and collective roots, photography has become my most intimate and personal space … it is a dialogue with myself and with what surrounds me,” Cosimo says. Here, the analog photographer on faith, field etiquette, and the future of popolari traditions.

Madonna delle Galline, Pagani (SA), Campania, Italia - Leica M6 _ Fujifilm Acros II 100

Madonna delle Galline, Pagani (SA), Campania, Italia - Fujifilm X-T4

Kate Causbie: Why do you choose to exclusively use film for this project?

Cosimo Pastore: The choice to use film was dictated not only by its aesthetic outcome, but above all by its ability to restore the value of time, of waiting, and of the craftsmanship of the photographic process. I chose the slowness and concreteness of film, giving images back their value as living objects, capable of aging, transforming, and telling stories that remain imprinted not only on paper, but also in the consciousness of the observer. Over time, this approach has become part of me.

KC: As a photographer, how do you approach a new event and the community around it?

CP: My first approach is that of a guest. I don’t take out my camera right away, but I observe, listen, talk to people. I try to understand what is happening, to immerse myself in the meaning of the event before documenting it. This attitude also changes the way I am perceived: I am not just a photographer who has come to “take” images, but someone who wants to understand and participate.

KC: Was there an encounter that crystallized that philosophy?

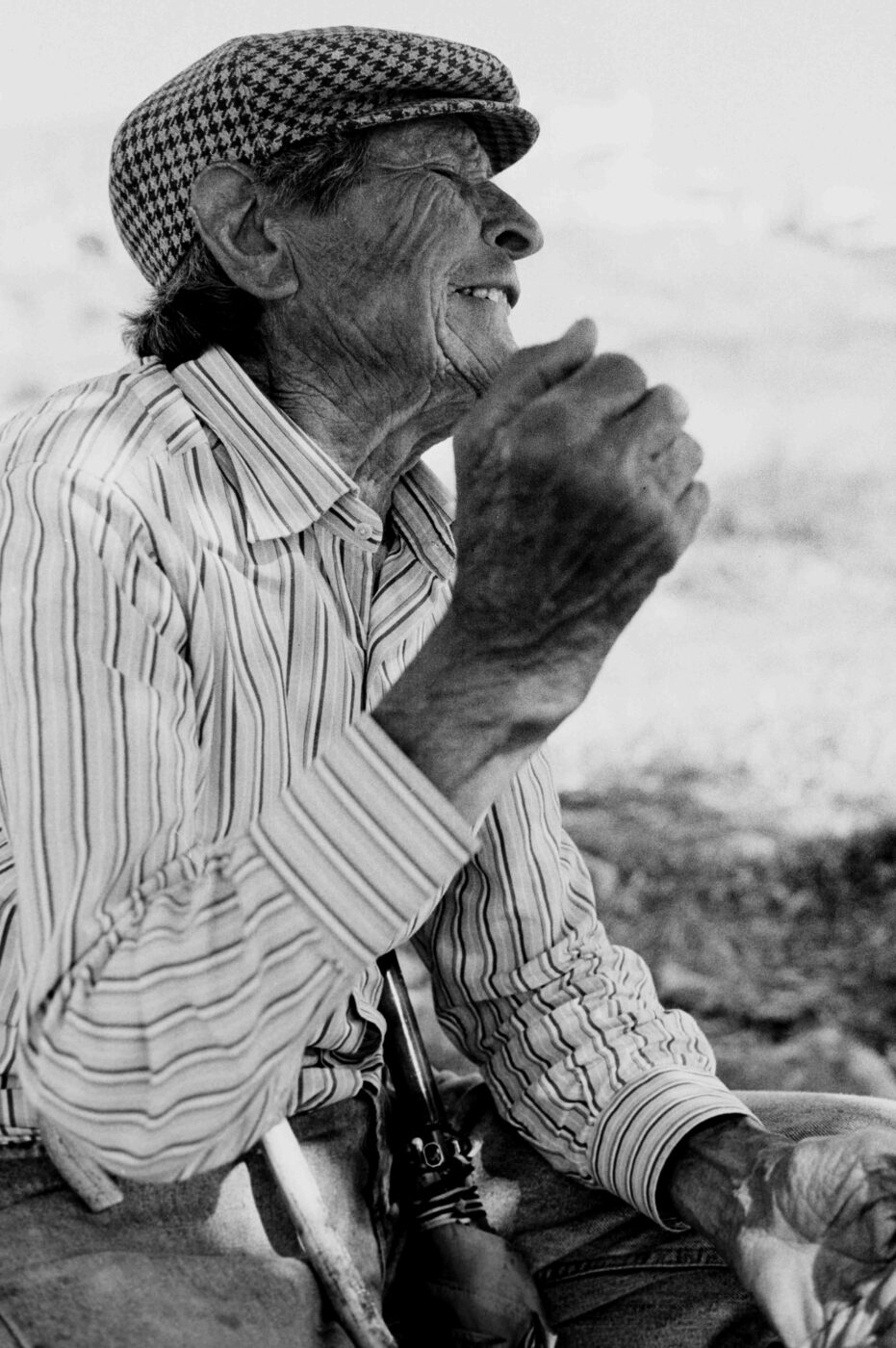

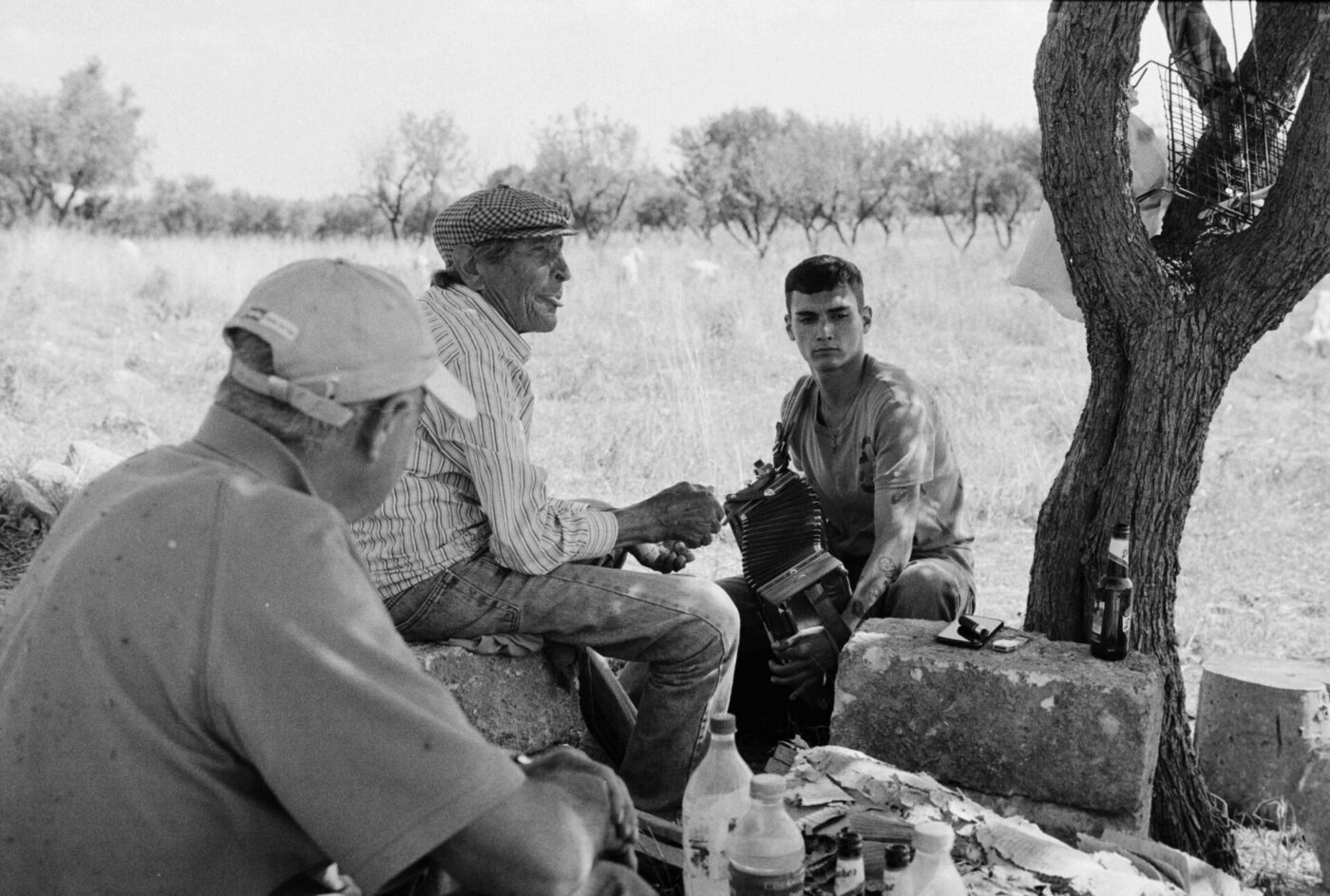

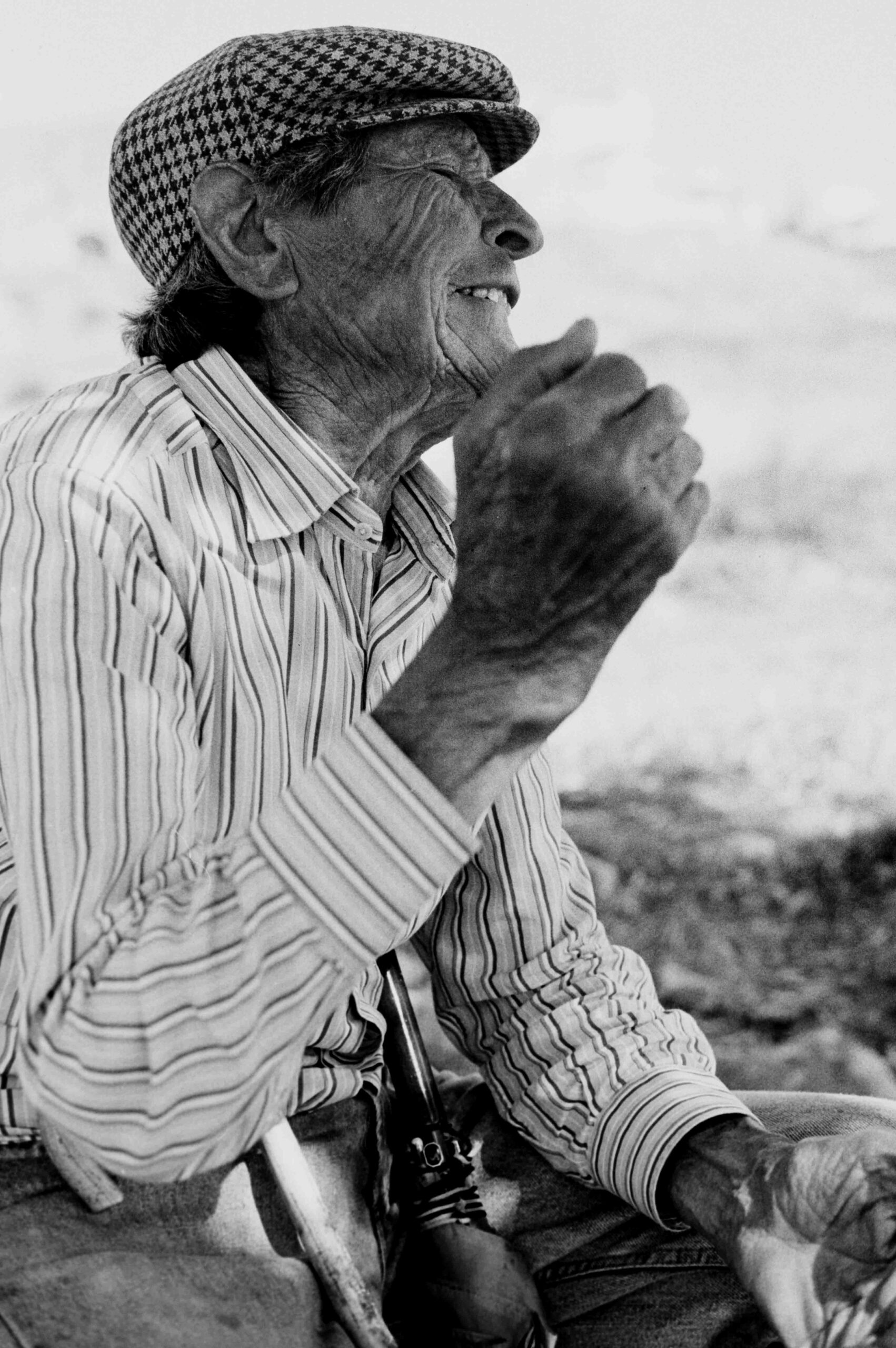

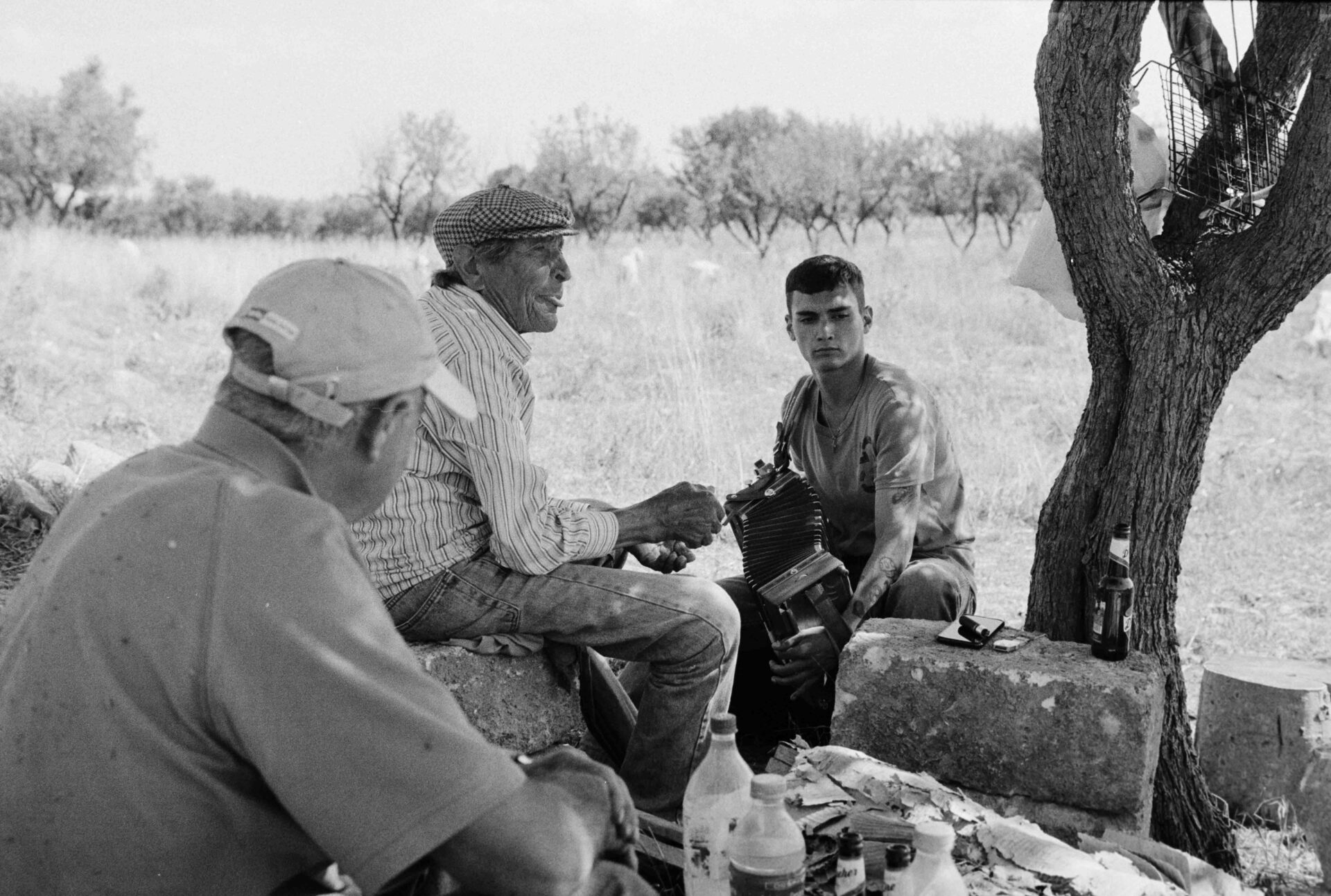

CP: I spent a day in the pasture with Vito Nigro, a shepherd from Villa Castelli known as Zi’ Vituccio: we talked at length, and I was fortunate enough to hear him sing, accompanied by the organetto of Matteo Scatigna, a young man who has made Vituccio’s oral and musical heritage his own. Those ancient melodies live on in Matteo, now that Vituccio is sadly no longer with us.

KC: And in that meeting—what stayed with you?

CP: Two moments in particular stuck with me. The first was that he began singing again, after a long time—a gesture I felt like a great gift. The second was what he told me, moved, when I gave him some Polaroids of himself before saying goodbye: “They come from all over the world to photograph me and interview me, but no one ever left me anything.”

In those words, in that tear that ran across the wrinkles on his face, I recognized the true meaning of that meeting.

Vituccio Nigro, Villa Castelli (BR), Puglia, Italia - Leica R4 _ Ilford FP4 plus

Vito Nigro e Matteo Scatigna, Villa Castelli (BR), Puglia, Italia - Leica R4 _ Ilford FP4 plus

KC: What would you tell others who are interested in photographing these festivals and traditions?

CP: If someone wants to bring their camera to an event, the most important advice is to do it with awareness and respect. Taking pictures should not mean interrupting, altering, or transforming the event into a spectacle for the lens. It should be an act of testimony and listening, a way to give something back to the community and not just to take images from it.

KC: Rural traditions like Vito Nigro’s are among those most at risk of being lost. What other pastoral customs have left an impression on you?

CP: In December 2023, I participated in a transhumance of Podolica cattle in Basilicata, traveling from Tito to Tolve (PZ). The transhumance was led by a young shepherd, Gerardo, with his friend Fabrizio, his father Luigi, and his brother. Together, they led the herd through a journey as evocative as it was unusual, alternating between mountain and woodland landscapes and almost surreal glimpses of the heart of Potenza.

KC: Did you reconnect with them afterward?

CP: Right now, I’m actually back with Gerardo and Fabrizio in Pignola, where they’re organizing a film festival. I was able to give them some prints of the photographs from that transhumance. It’s a great gift to witness the reactions of people when they see themselves in my shots: as if those images give them a fragment of life, of memory, of truth.

Transumanza, Potenza, Basilicata, Italia - Leica M6 _ Kodak T-Max 400

Transumanza, Potenza, Basilicata, Italia - Leica M6 _ Kodak T-Max 400

Transumanza, Potenza, Basilicata, Italia - Leica M6 _ Kodak T-Max 400

KC: The Italian word “popolare” refers to the fact that traditions are held in the hands of the people. What does that mean to you?

CP: “Popolare” culture is passed down orally, creating a collective heritage to be protected from generation to generation. This human exchange is the foundation of my approach. When someone chooses to share their story, they inevitably share a fragment of their experience and soul. It’s a gesture that inspires gratitude, but also a strong sense of duty.

KC: You mentioned early experiences tied to religious rites. How do you see the presence of devotion and the Church in the traditions you photograph?

CP: Faith is the driving force behind many of these events, but it expresses itself in different ways depending on the context.

For example, in Marian celebrations, such as those of the Madonna del Pollino or the Madonna di Montevergine, I’ve noticed how the feeling of devotion is deeply rooted in an ancestral bond with the maternal figure. At the Madonna delle Galline, what struck me most was the fusion of the sacred and the profane: confetti and streamers fell from the overcrowded balconies while the procession slowly advanced through the crowd. Parents lifted their newborns towards the Madonna, in a gesture full of faith and hope, while the songs and dances mixed in a vortex of sounds and movement.

KC: And in others?

CP: On the other hand, in penitential rites such as those of Holy Week or the Seven-Year Rites of Guardia Sanframondi, the religious dimension merges with practices that often go beyond ecclesiastical orthodoxy. Physical pain becomes a language of atonement, an act of individual redemption.

Many religious celebrations have become mixed with elements of spectacle: processions are accompanied by market stalls, lights, and a more festive dimension. However, the intensity with which certain people experience these events demonstrates that, beyond the transformations, faith and devotion still remain fundamental elements in the identity of many communities.

KC: You’re also a musician—what role does music have in these traditions?

CP: Music plays a fundamental role in traditions, which have their roots in ancestral rhythms and in the voices of tradition bearers, people who preserve oral knowledge through songs, ancient instruments, and melodies belonging to the collective memory.

KC: And how do sound recordings complement your frames?

CP: Through the collection of environmental sounds, I can reconstruct a broader picture of the culture. Photography captures an instant, but sound restores the depth of time: the beat of the drum on a festive night, the voice broken by emotion during a funeral lament, the spontaneous chorus of a community singing to feel united.

Madonna del Pollino, San Severino Lucano (PZ), Basilicata, Italia - Leica M6 _ Kodak Portra 400

Madonna delle Galline, Pagani (SA), Campania, Italia - Nikon F4s _ Kodak T-Max 400

Madonna di Montevergine, Mercogliano (AV), Campania, Italia - Hasselblad 500c - Kodak T-Max 400

KC: What are your hopes for the future of popolari traditions?

CP: I believe that traditions are the heart of a people’s identity, the invisible threads that bind generations and tell us who we are. It’s not enough to preserve them: we must allow them to adapt to the times without losing their nature.

During the residency funded by the European Union’s “Culture Moves Europe” program, I had the opportunity to delve deeper into this concept by studying Castells in Catalonia [in this cultural practice, teams called colles castelleres build towering structures of people]. Seeing these human towers take shape before my eyes was incredible: each person has a specific role, and everything is based on mutual trust and the strength of the group.

Tradition continues to exist because people choose to be part of it, to support it, and to pass it on.

KC: And for the future of Analog_Trad?

CP: I want to continue to document, share, and create connections between traditions that are distant in space, but close in spirit. Because, after all, tradition is exactly this: a bridge between past and future, a legacy that continues to renew itself in the hands of those who live it.

This interview has been translated from Italian and edited for clarity.

Festa di Sant’Ursula, Valls, Catalogna, Spagna - Nikon F4s _ Kodak Portra 400

Concurs de Castells, Tarragona, Catalogna, Spagna - Nikon F4s _ Kodak Portra 400