The body, desire, emancipation, beauty, motherhood, struggle, expectation, and (mis)representation—all of this and more is captured in the face of a woman. But when we look at her photographs, what are we really seeing? What stories are we crafting about her, and how much of that is shaped by the subject herself, the photographer behind the lens, or our own biases?

As a woman and a photographer, I believe that female photography is wrapped up in an unlimited list of desires: the desire to be admired and loved; to show ourselves, with or without clothes; to make our bodies political manifestos; to seduce; to occupy a space, a time, a way of living; to overturn clichés; to self-determine. The type of photograph or medium doesn’t matter, but the goal: to take ownership of an image and make it one’s own.

To get behind the female gaze, I spoke with 11 female photographers who most often turn their lens to the fairer sex, and who are from or have worked in Italy. Their work spans various genres–fashion, travel, weddings, motherhood, analog photography, nudes, and portraits. In the following mini-interviews, we talk about what it means to pay homage to the female body, the effects of censorship, and the common desire to be heard and to feel united.

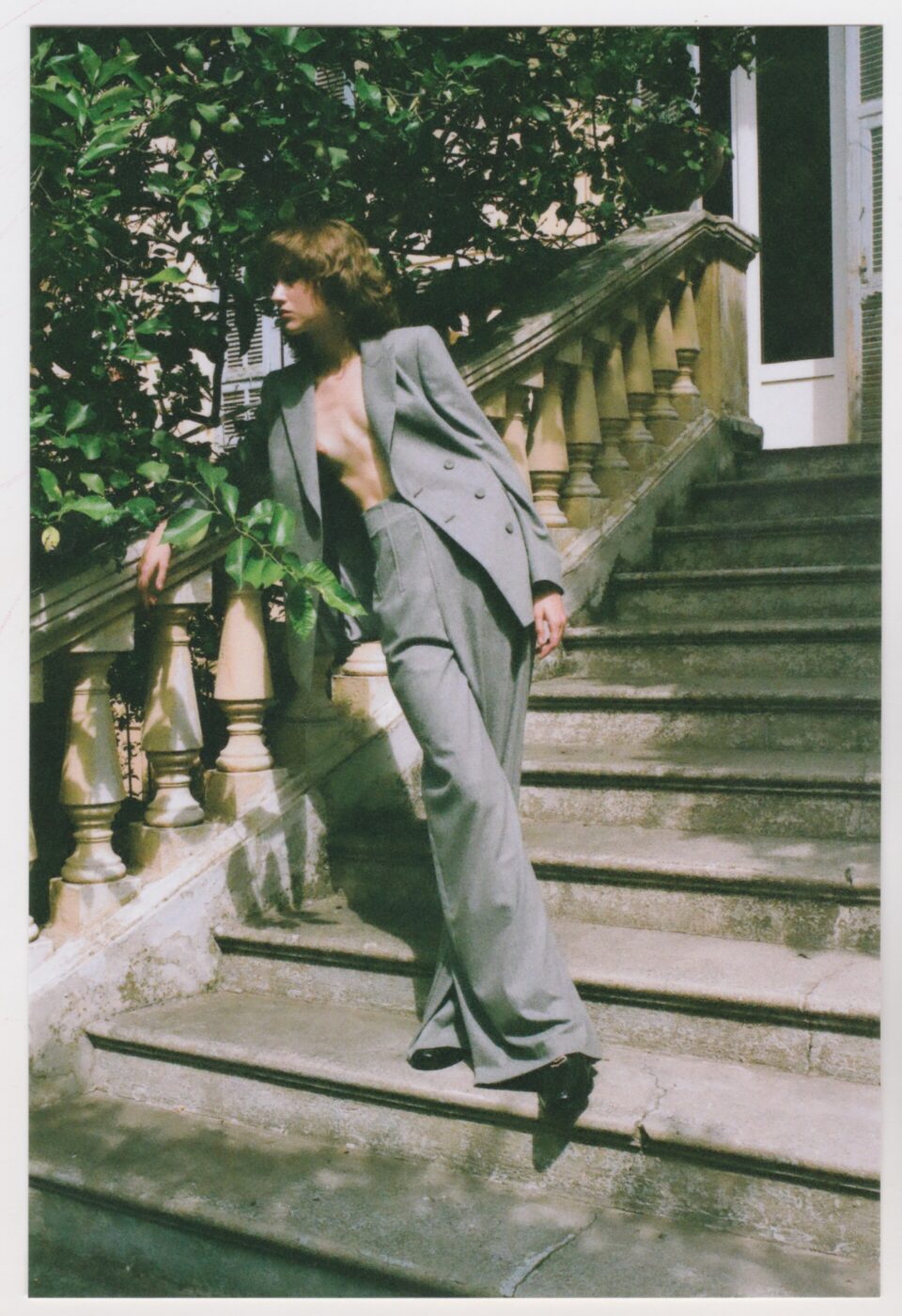

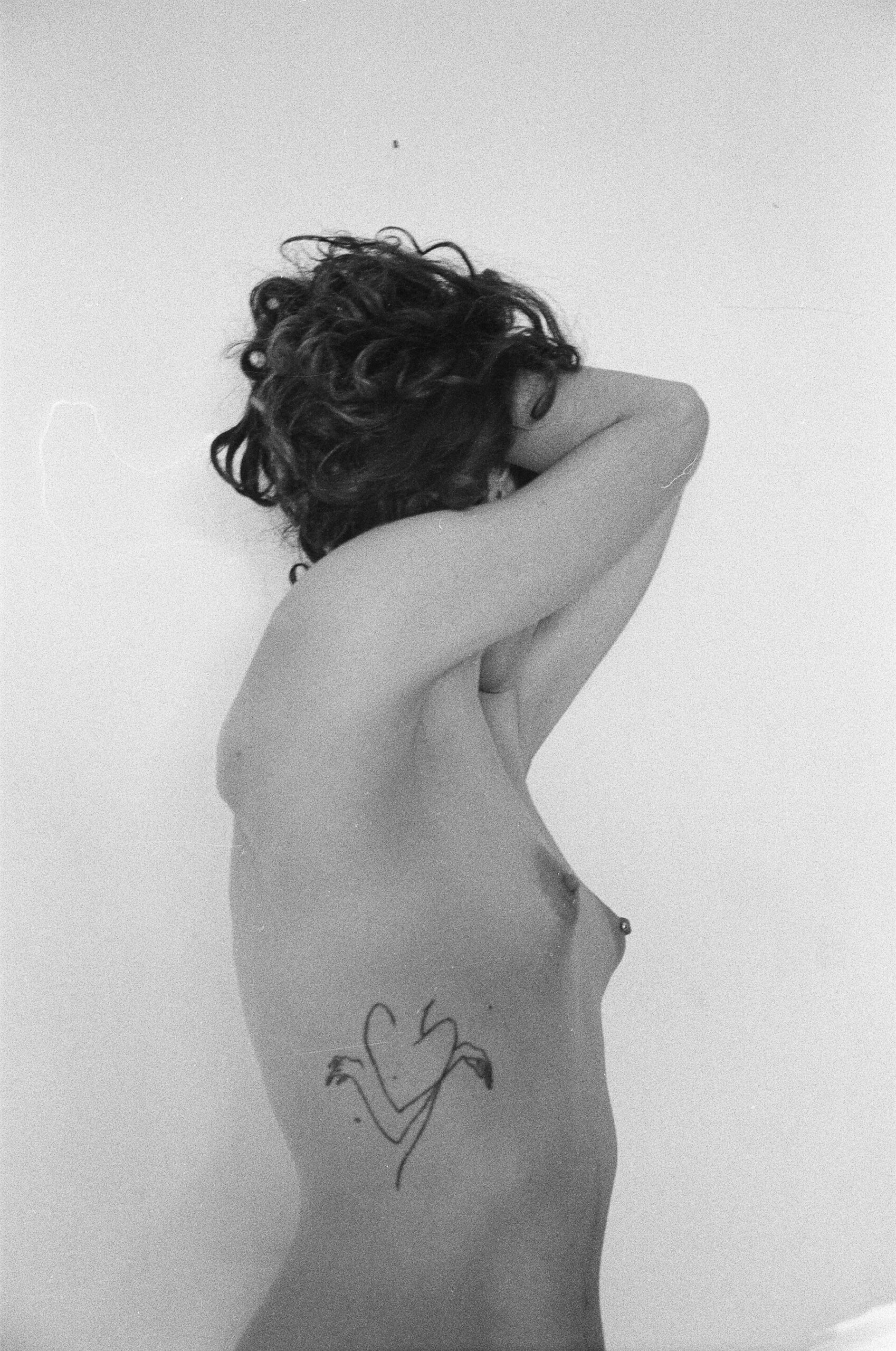

Photos by Deborah D'Addetta

SERENA SALERNO

Serena Salerno, born in 1991 in Torre Annunziata, Naples, found her love for photography at 18 when tinkering with her father’s cameras. Drawn to the tactile nature of analog photography, she’s most inspired by the complexities of the provincial life that shaped her. Today, she splits her time between Marseille and Paris.

DD: You shoot mostly women, often naked or semi-undressed, and self-portraits on film. Why do you think female nudes always create a stir, especially when shared on social networks? How do you come to terms with your art, especially when censorship prevents you from expressing yourself as you would like?

SS: Women are and always will be among my favorite subjects; through them, I can get to know myself. I see photography as a way to reflect ourselves in others, helping us discover more about who we are. In the history of art, women have always been protagonist figures, and it’s sad to see how our representation has changed over time. Today, unfortunately, social media is the most widely used channel for sharing one’s work, but no artist’s goal is to have their work viewed on a phone screen. Photographic prints allow viewers to engage deeply and directly.

Plus, social networks constantly suggest the “ideal woman”, filled with unsolicited advice on how to dress, what diet to follow, what sport to play. When a woman is portrayed in her true, sacred essence–embodying creation, strength, and mystery–rather than as a marketable object, the fear of her power fades. Historically, this has been suppressed in favor of a commodified “woman 2.0” image that sells but lacks authenticity. I don’t let this limit my photography, but I come across censorship even when nudity is not present. If I could do without it, I’d delete my social networks today, but it’s common to feel that we have no other alternatives. The important thing in all this is not to get lost.

DD: As a woman and a photographer, what do you think is the most genuine way to represent women and our relationship with our bodies?

SS: I believe it’s all a question of energy. If we approach our subjects with judgement or preconceptions, we won’t be able to accurately represent them. Photography is about listening. You have to be open, waiting to be surprised by what you hear. It’s a game of mirrors, and if the photographer has already assigned a story or role to the subject, then that’s what will come out.

Photos by Serena Salerno

LENA AIRES

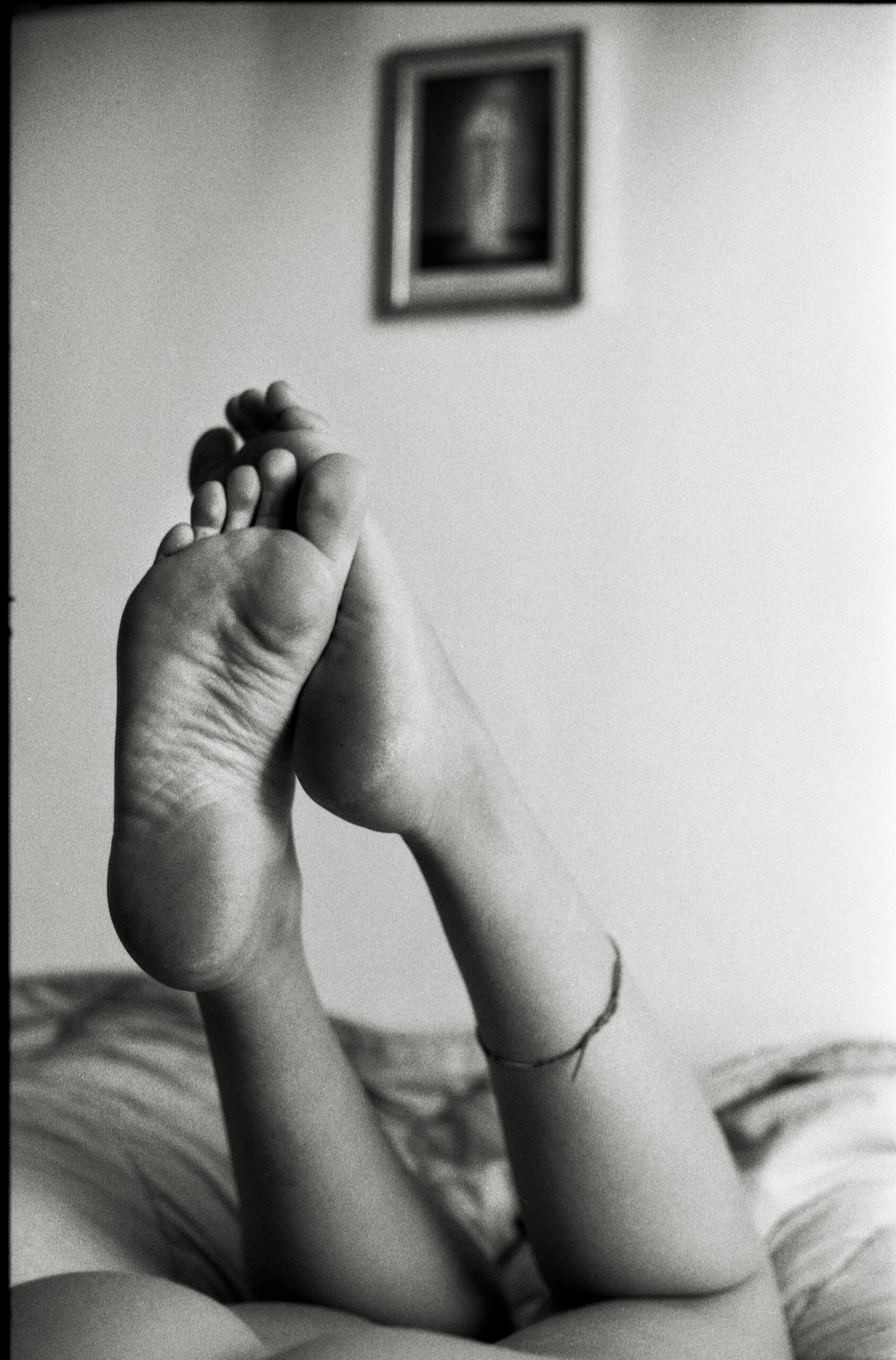

Wales-born, London-based photographer Lena Aires grabs her film camera to shoot the things she loves: the spiritual, nature, animals, and intimate, quiet, and tender moments. Each photograph is an exploration of the meaning in the ordinary, and her portraiture, still life, and documentary imagery seem to blend memory and place. She also organizes photographic retreats in Italy.

DD: You shoot exclusively on film, a medium that allows you to be intimate, almost dreamy. In your self-portraits and portraits of other women, the relationship between light and the exposed body is key; skin is revealed in a way that feels almost like a painting, focusing on beauty and form without any voyeuristic intent. What prompted you to shoot this way?

LA: I feel like the themes of nature, nakedness, light, delicacy, and curiosity interweave quite harmoniously in the world, and thus also in art and on film–that is, they are all natural, organic parts of life in which we find fullness, meaning, and beauty. They all stem from deep human desires–the desire to feel more connected to our surroundings, to allow ourselves to be vulnerable, to be receptive and open to experiencing more of ourselves and life around us.

I’m drawn to tender moments and the fragile, ephemeral things that bring us closer to beauty, to meaning. Patches of light, bare skin, nature, human gestures, animals, and plants–all, I feel, are inherently earthy and sensual experiences.

DD: As a woman and a photographer, what do you think is the most genuine way to represent women and our relationship with our bodies?

LA: I think we should aim to be our authentic selves as much as possible. There’s always an element of mystery when taking photographs and in choosing what we share and how we share it. I think it’s fine to leave things up to the imagination, to not reveal everything about ourselves, if that is what we desire. But we should also be open to being vulnerable and sharing our life experience, in whatever capacity that looks like for you personally. Everyone is different, and how we choose to present ourselves is up to us and us only. I hope for women to feel that they have the freedom to experiment and be playful with the way they portray themselves and other women–to allow themselves the time and space to be creative, regardless of outside opinion.

Photos by Lena Aires

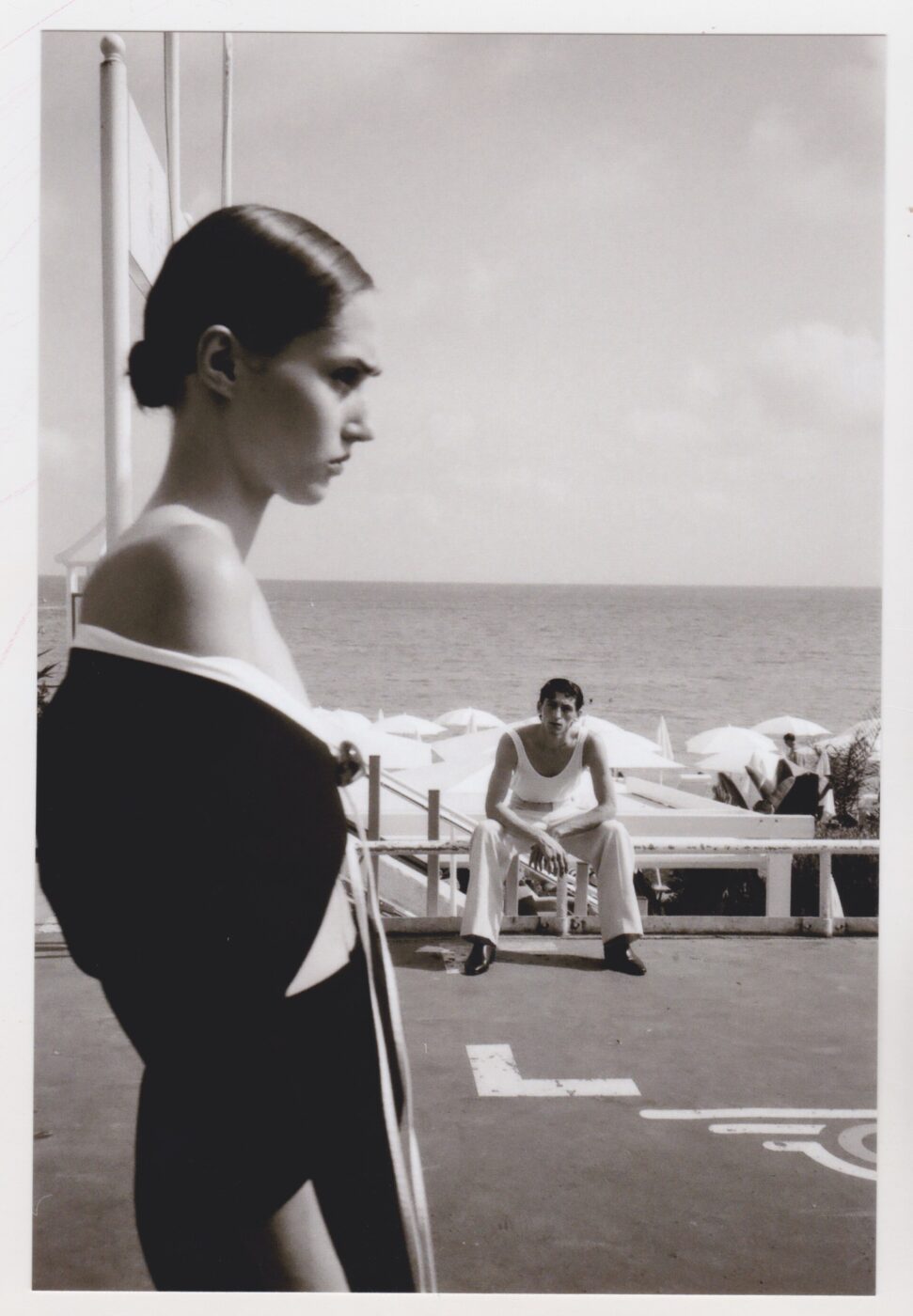

ELISE WOUTERS

London-based visual artist and writer from Belgium Elise Wouters explores longing, solitude, and sensuality through her analog art and darkroom processes. You might have seen glimpses of her work in Vogue, Huck Magazine, or The Independent, or in her first photobook Voglia–the result of residency in Palermo–published with 89books in 2023. Her next body of work centers around photogravures–stay tuned.

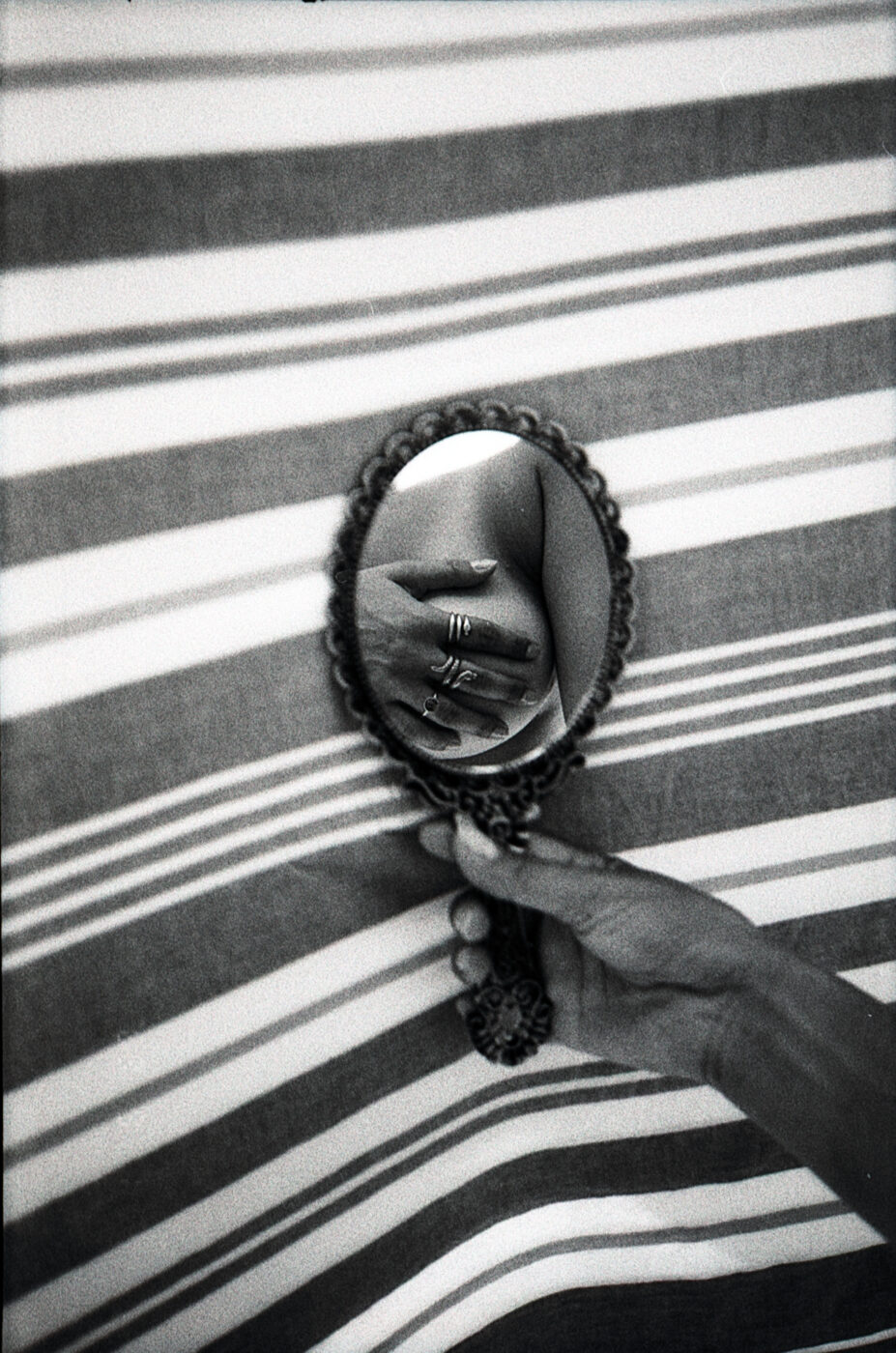

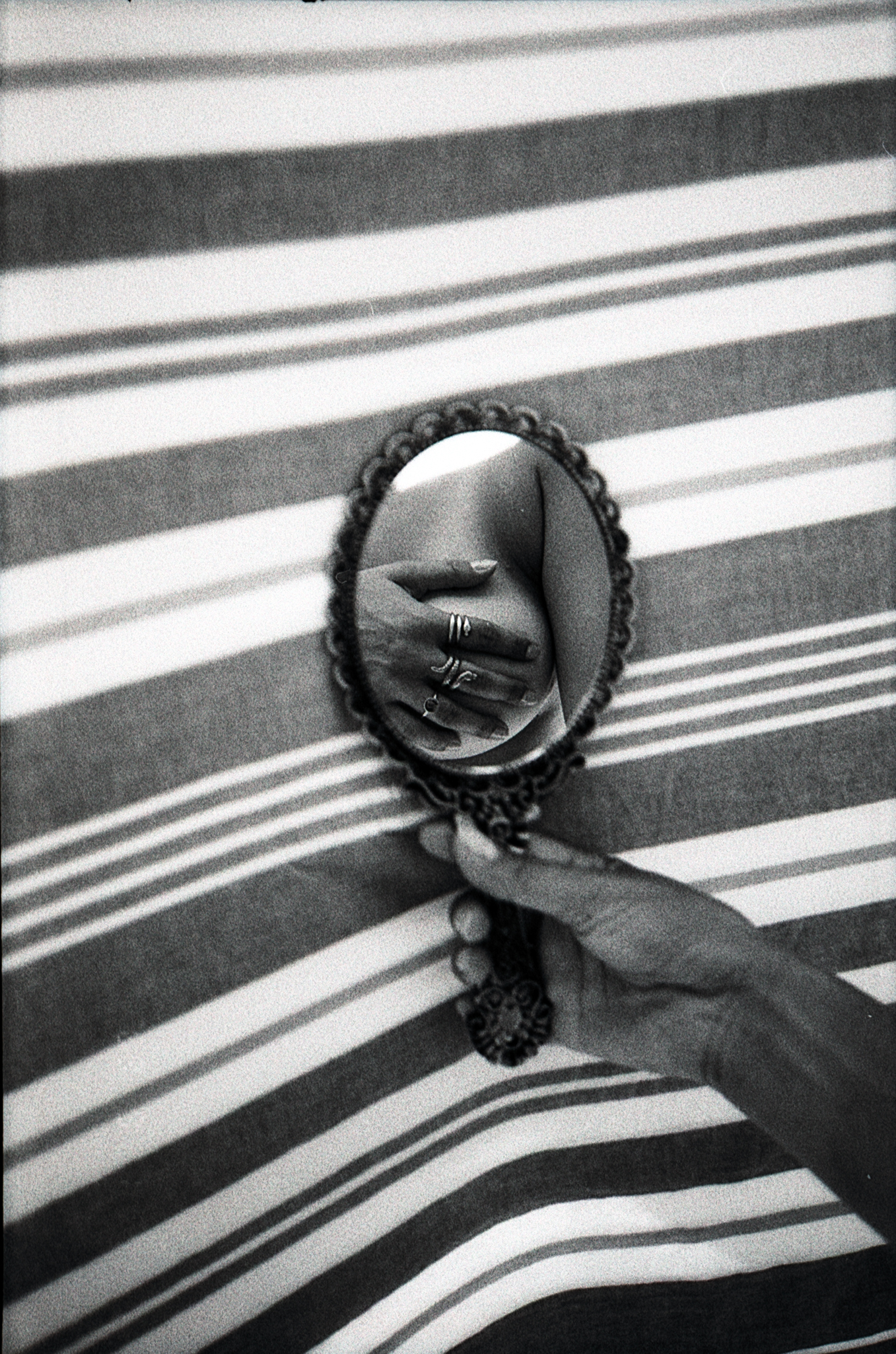

DD: Your photographs often represent femininity linked to both sensuality and loneliness, and you experiment a lot with your figure, see-through mediums, analog selfies in the mirror, and small letters dedicated to yourself and other women–thoughts, poems, declarations of love. What are you trying to discover through your artistic process?

EW: I’m interested in exploring how time spent on your own can hold sensual potential–to be alone (but not lonely) makes space for the imagination. In my photography, each frame is a search for transcendence. My process is a conversation with memory, and the end result is almost secondary to the journey. I play with recurring motifs of reflections and writing to enable this conversation. At the same time, the work is in dialogue with a larger framework; intimate narratives have the ability to resonate on a more universal scale.

At the heart of this examination lies the analog format. I slow down the process by shooting, developing, and darkroom-printing everything myself. Each step becomes infused with meaning, since the limitations (36 frames, chemical development, etc.) force me to make considered choices. Analog guides you to celebrate, not just embrace, uncertainty and imperfection. I find echoes of this in being a woman and in my relationship with my own body.

DD: As a woman and a photographer, what do you think is the most genuine way to represent women and our relationship with our bodies?

EW: I think freedom is essential to artistic expression and representation. To be free to express yourself is the greatest source of joy for me, and I’m aware that many women globally still don’t have that freedom; to create, to uncover your own truth, and to find pleasure, energy, and empowerment in that self connection. Authenticity currently plays a big role in photographic expression. Personally, I’m more interested in playing with the borders of self-representations: I love the nuance of storytelling, creating a narrative, inhabiting a character, and even enlarging a certain aspect of my personality.

Photos by Elise Wouters

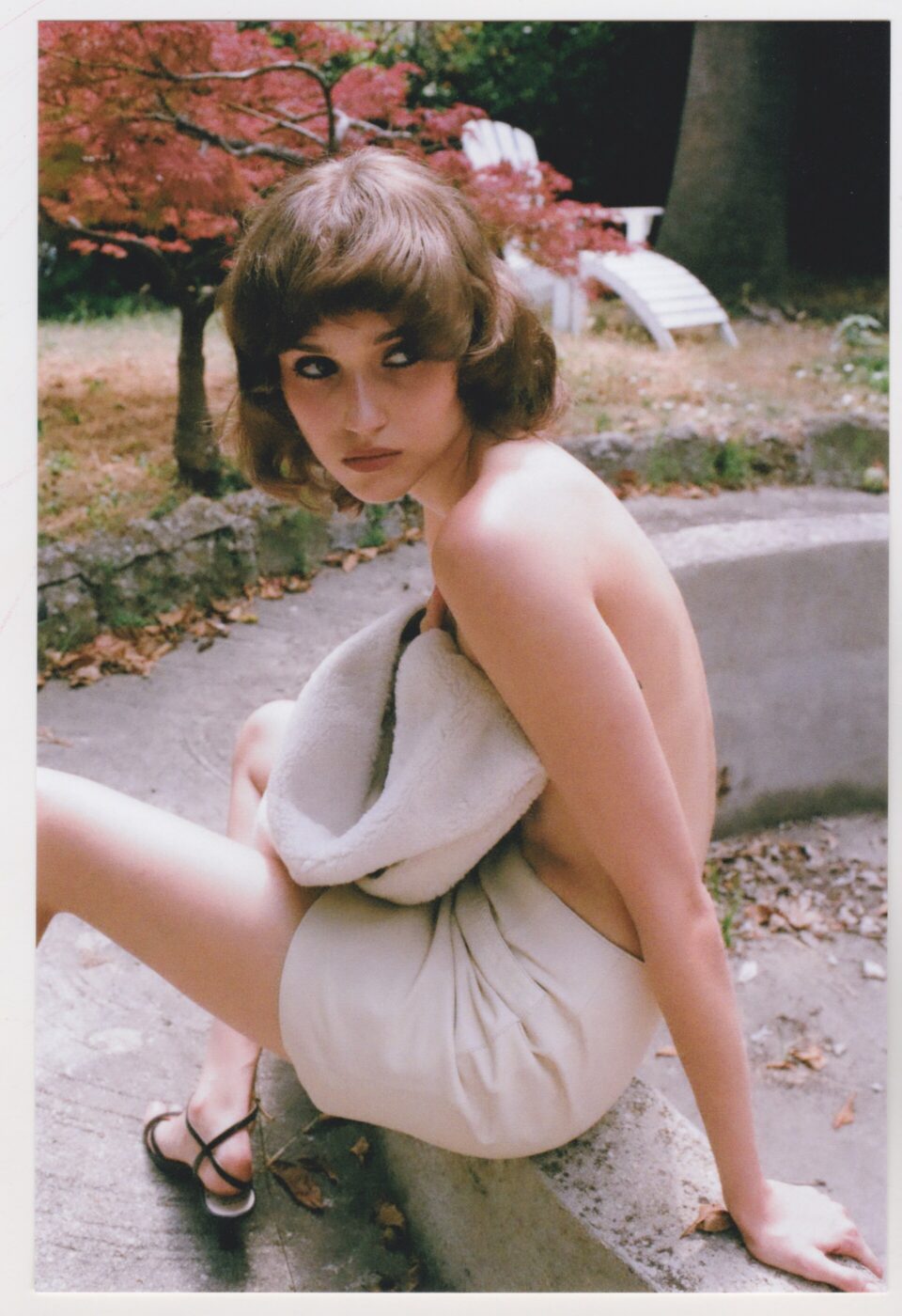

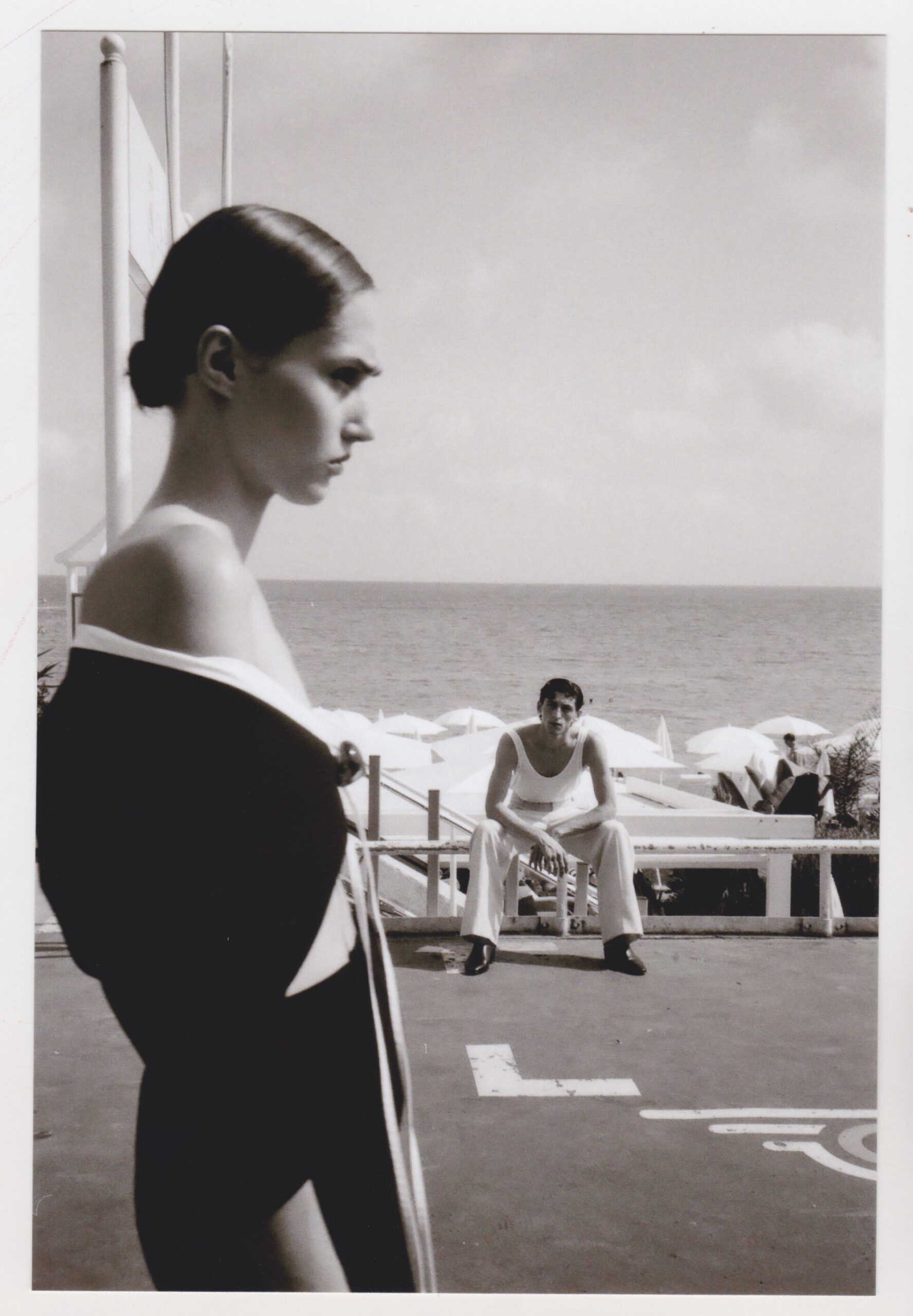

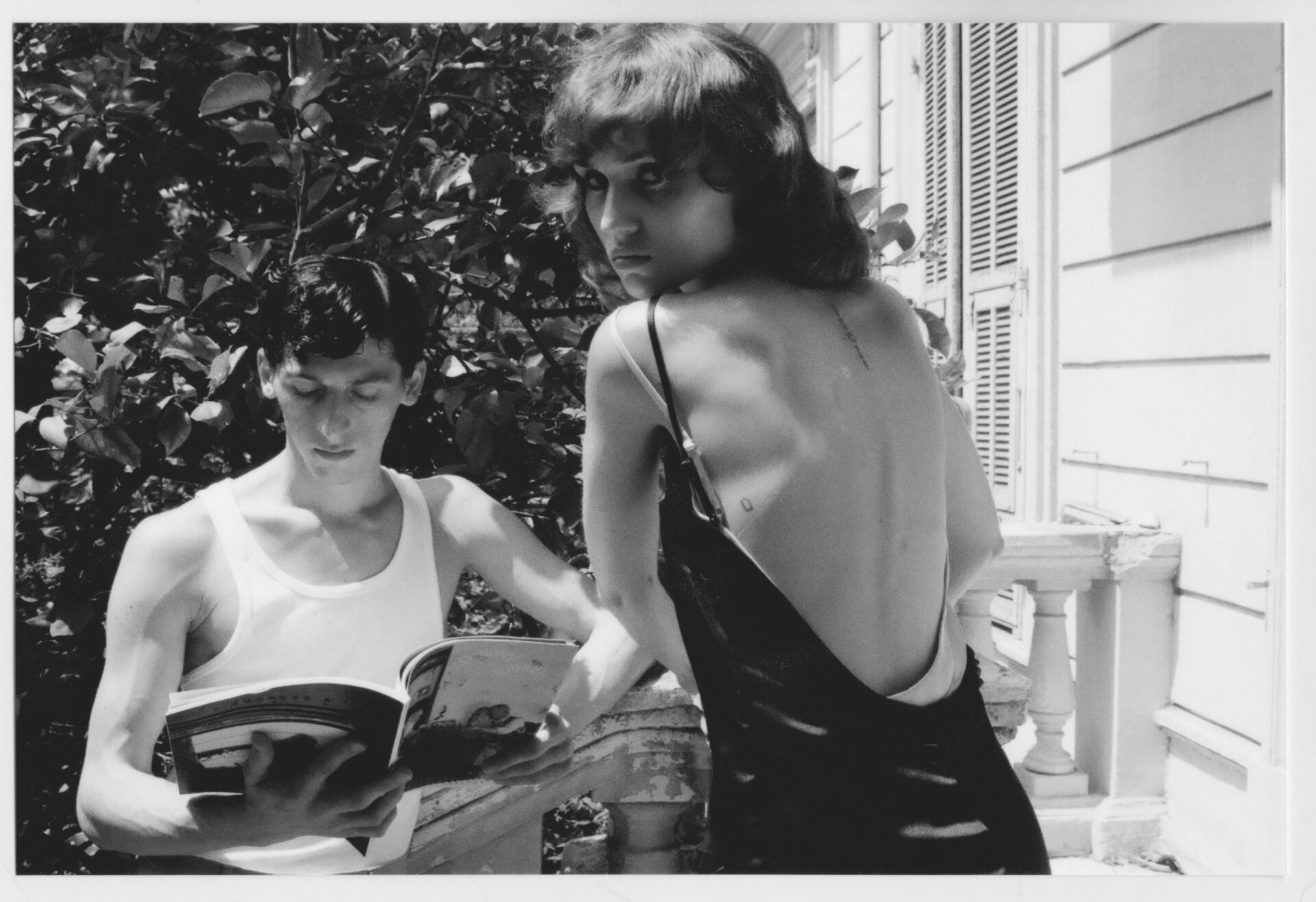

LAVINIA CERNAU

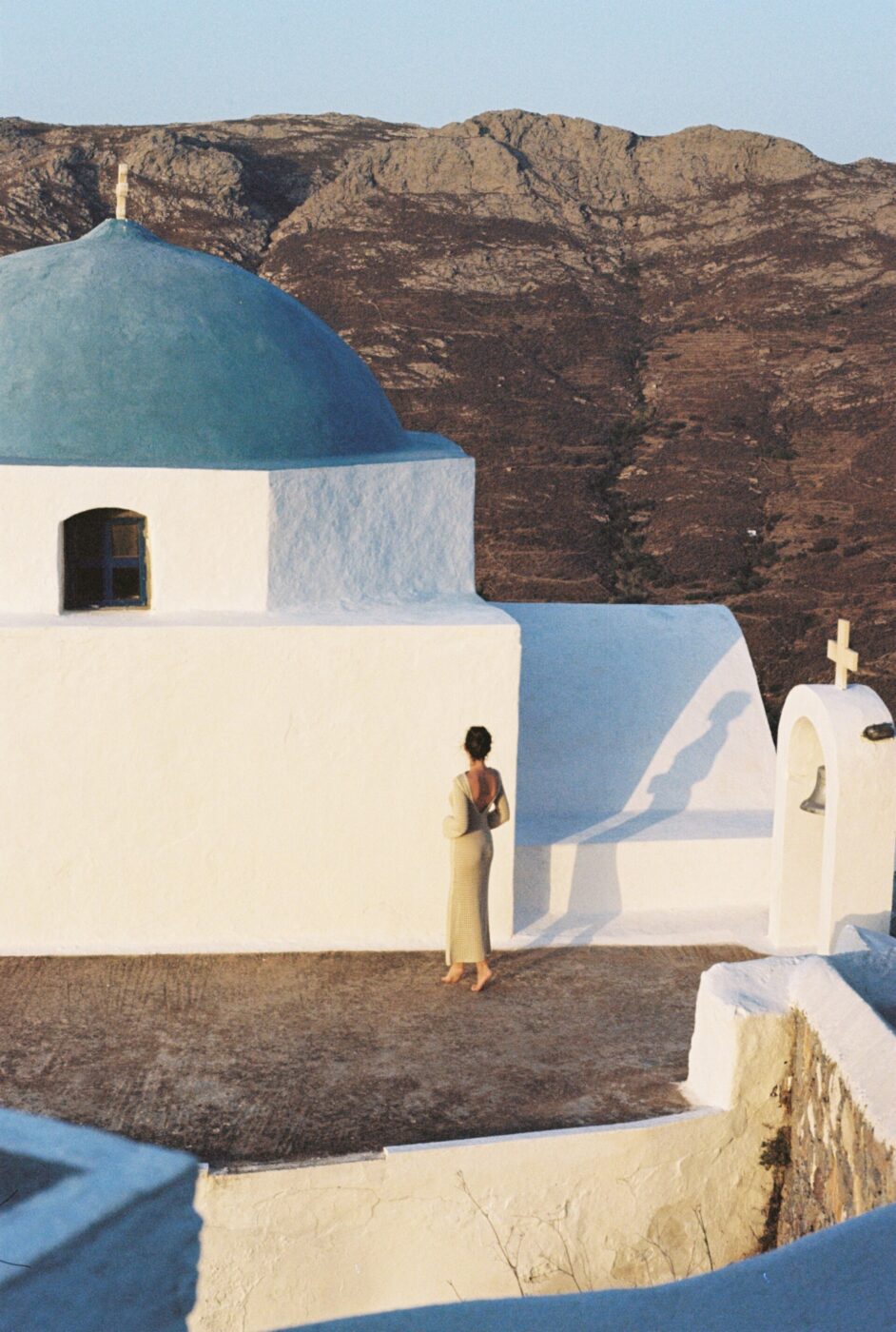

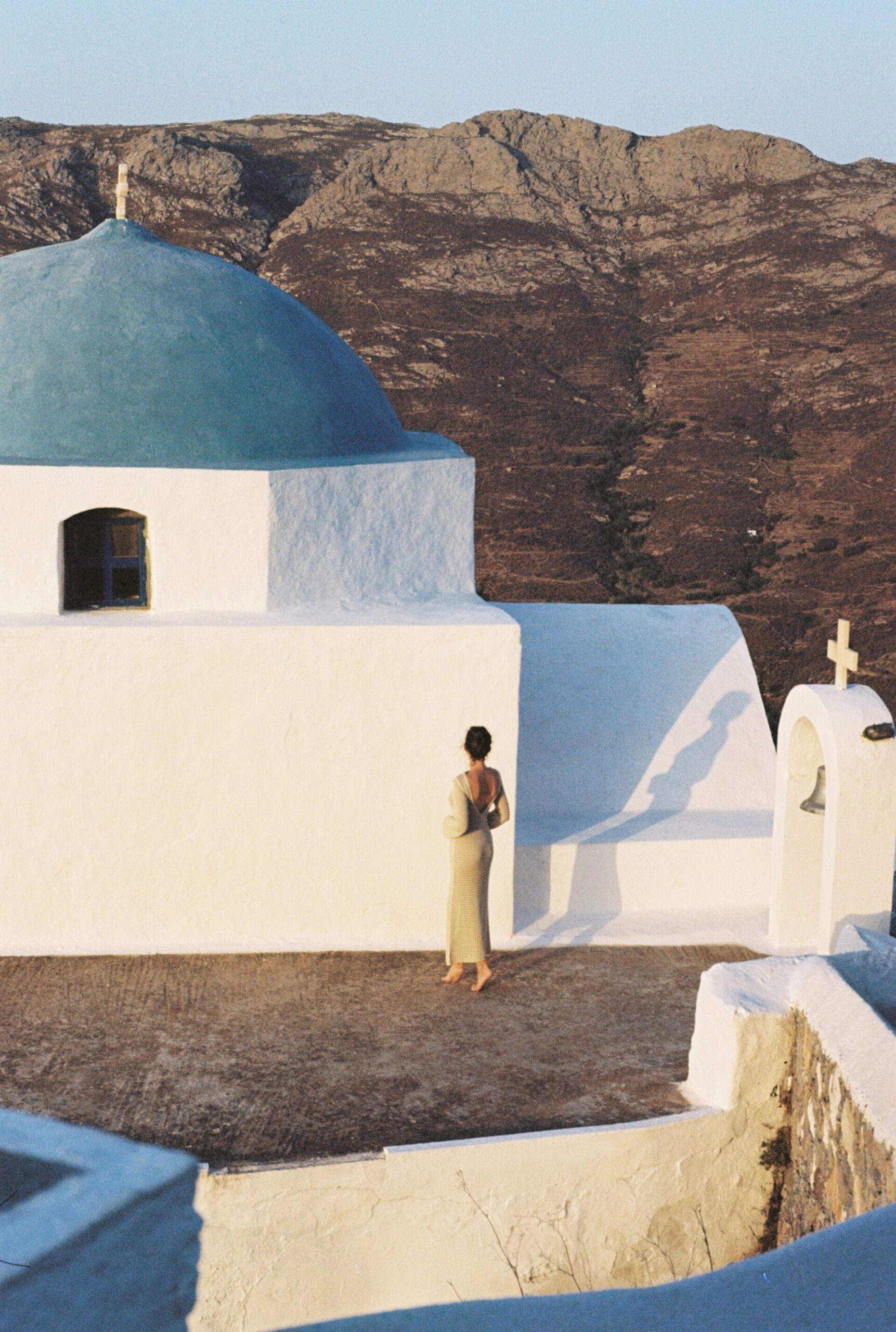

Transylvania-based Lavinia Cernau is a travel, fashion, and lifestyle photographer with a penchant for the Mediterranean. Her work has a specific emphasis on mundane moments that come to be suspended in time, and many of her photographs have that cinematic golden hour glow. She’s a regular contributor to Condé Nast Traveller.

DD: Your photographs are deeply linked to the sea, summer, and a feeling of sharing and freedom. Why is the sea so important? How do you link women’s bodies to the nostalgia of summertime?

LC: It must be that I’m inextricably attracted to the sea; it’s such a primordial element that harkens back to the freedom of being ourselves, to the ancient times when we were one with nature. When I photograph in that golden light, it’s like everything becomes possible. I’m trying to hold on to that moment of carelessness and abandonment to the elements, somehow.

DD: As a woman and a photographer, what do you think is the most genuine way to represent women and our relationship with our bodies?

LC: As women, we’re under constant scrutiny and judgement even among ourselves, let alone by others. As I get older, I like to think I’m becoming wiser (LOL) and so I’m more and more convinced that it’s all about keeping a good balance…with everything. And when it comes to portraying women, I’d just like to dwell in the thought that I’m doing my absolute best to portray them in an honest and true fashion, that my images reflect their humanity and beauty, both their inner and outer qualities. I guess you could say my aim is to capture a little glimpse of their souls when I press the shutter.

Photos by Lavinia Cernau

SERENA RUSSO

For Serena Russo, photography is like therapy. She first picked up a camera during her university years at the Academy of Fine Arts in her hometown of Naples, studying and graduating in Fashion Design. Her photographs have been on exhibition in Paris and Milan and featured in various international magazines.

DD: You have a flair for portraits, often portraying an extremely intimate and melancholic mood. How do the women you photograph reflect your perspective on women and their role in the world?

SR: I have a tendency to reflect myself a lot in the faces of the women I photograph; often, the melancholy I carry with me finds space in their looks, in the shadows and light I choose, especially for those personal works where I free myself to create without boundaries. Photographing their bodies is a reconciliation with the perception I have of my own. I like to think that through the images I create, each of those faces can feel understood in a certain sense; that although we live a life that wants us to be perfect, there’s instead other things to dwell on, the things deep inside that make us unique.

DD: As a woman and a photographer, what do you think is the most genuine way to represent women and our relationship with our bodies?

SR: I believe the most authentic way to represent women is to abandon stereotypes and instead embrace their freedom, vulnerability, scars, and all the qualities that make them unique. Women should be seen as individual universes, defined not just by their bodies, aesthetic perfection, or roles like motherhood, but by the countless other nuances that reflect their complexity.

Photos by Serena Russo

ILARIA TOMA

An art lover since childhood, Salento-local Ilaria Toma is a self-taught street photographer. While studying French and Italian sign language in Venice, she began to experiment with photography, trying to capture things that can’t be seen by the naked eye.

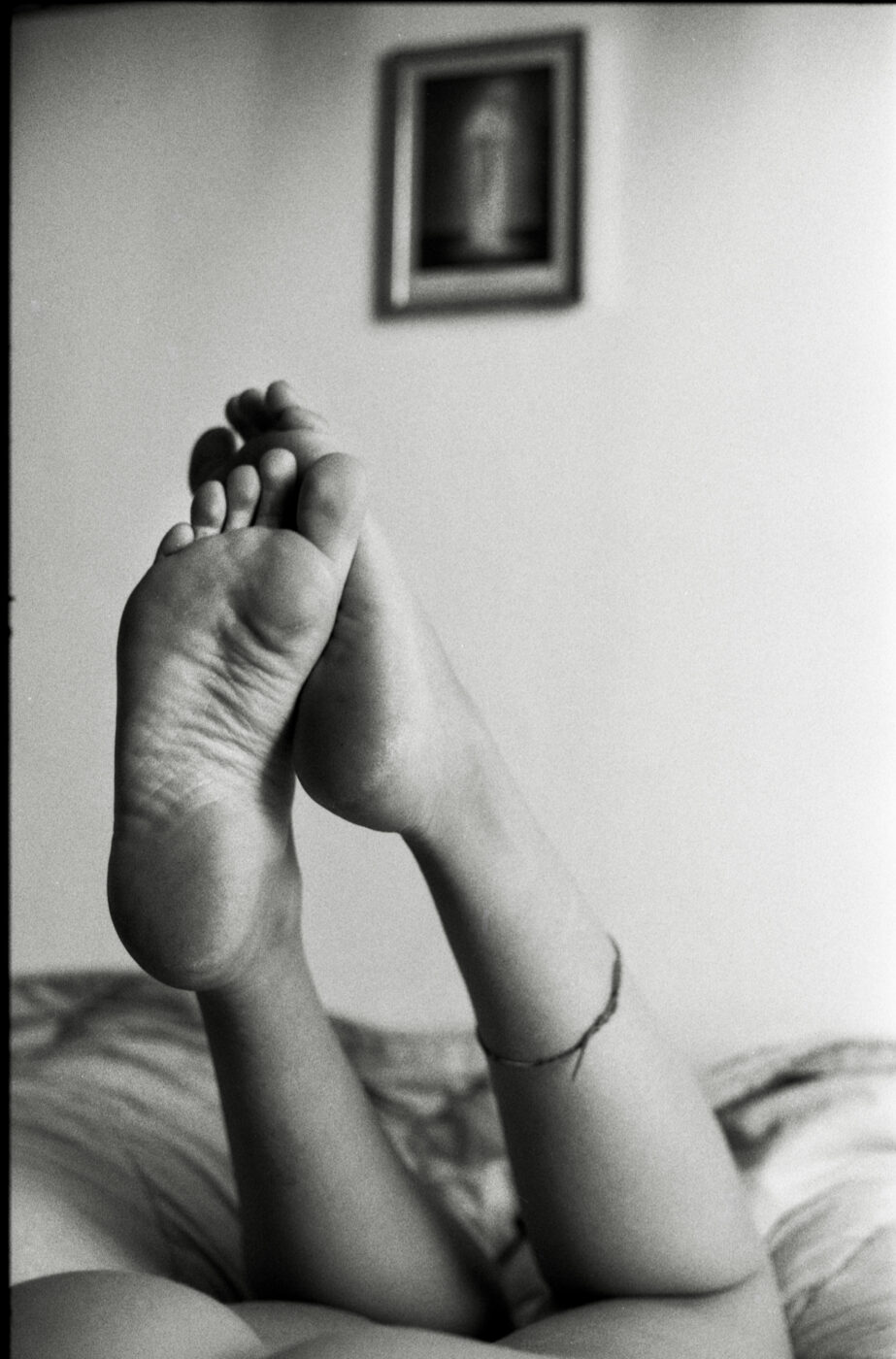

DD: Your photographs seem to investigate more than the body, but the feelings and the soul of a subject, evoking a vague eroticism linked to the intimate spaces of the home. Why this, and love, as primary themes?

IT: I firmly believe that love is the motor of everything: love for oneself, for one’s surroundings, for people, for life in general. I can’t think of a day without overflowing love; the concept is all-embracing. Perhaps in recent times this word has lost some of its power, made almost banal, but for me it remains the only thing that matters. It’s about passion and care, a vision of life based on the beauty of imperfection, truth, details, purity, and kindness. When I speak of love, I don’t only mean love between two people, but I consider it an artistic concept and vision of life. A girl once told me that the beauty you grasp is endurance. Exactly that. Love is endurance, and what I try to capture in every shot.

DD: As a woman and a photographer, what do you think is the most genuine way to represent women and our relationship with our bodies?

IT: I’d like women to be portrayed delicately, carefully, and attentively, how they want to be shown. Whenever I photograph a woman, I ask her to be totally free to do and wear (or not wear) what she wants, to be what she wants. The most honest way to tell the story of a woman is to listen to her. Each of us has different facets, and whoever chooses to narrate a woman should try to capture at least one of them. It takes depth; otherwise she’s just a cliché.

Photos by Ilaria Toma

MARIA FLAMINIA BARI

When leafing through magazines as a child, Maria Flaminia Bari wasn’t inspired by the fashion, but by the photography, and she began to obsessively photograph everything around her. She really got into her groove when she moved from Siena to Bologna in 2019, combining her passion with her love of music. After stumbling upon an old film camera in her home, she now mainly shoots analog.

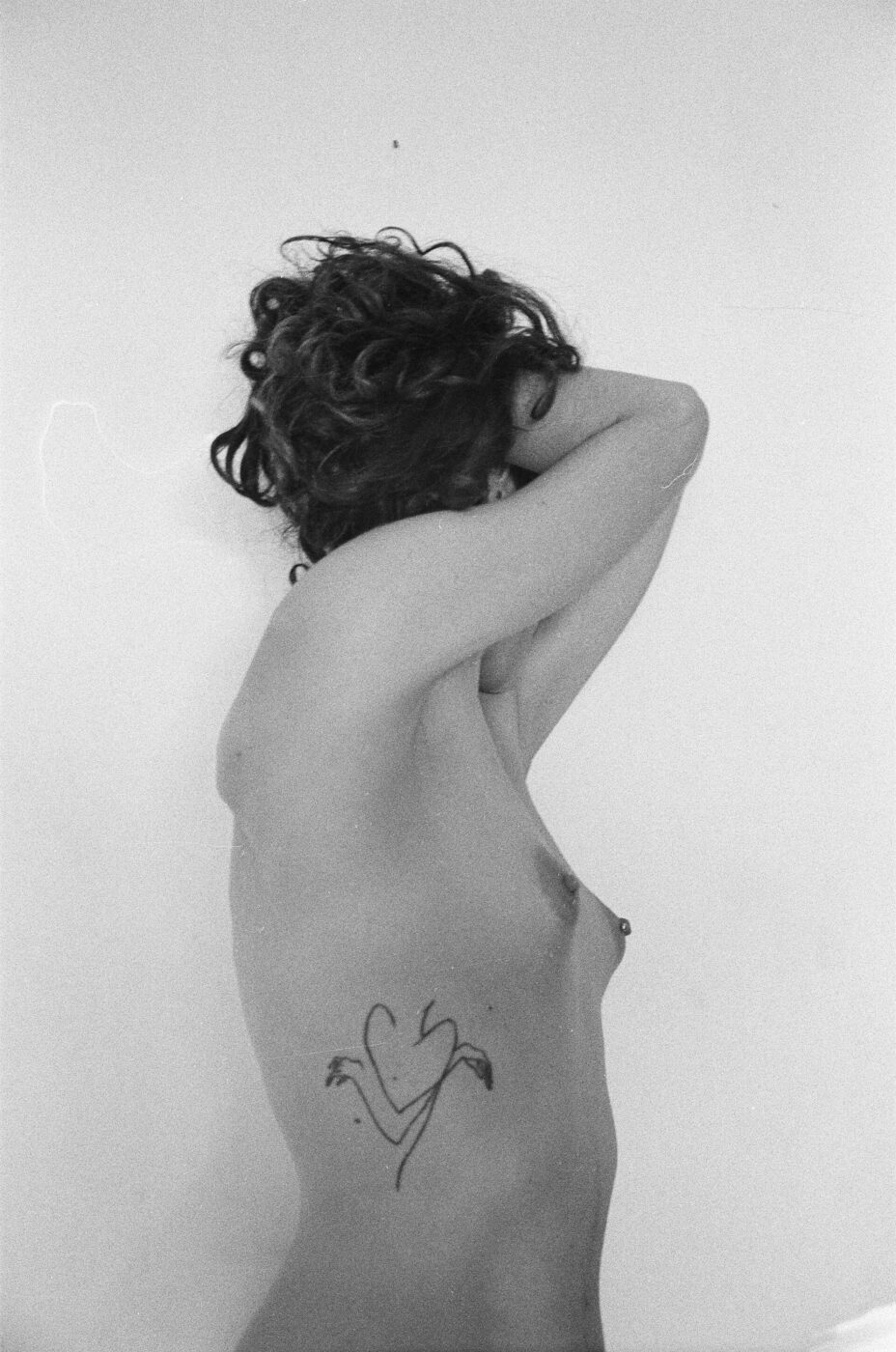

DD: In your project “Undressed soul”, you portray nude women with a contemporary approach that’s a bit punk, transgressive, free from the fear of showing the female body as something to be ashamed of. How politically charged is this message? Why do you think female nudity always creates controversy, especially when it comes to personal freedom and censorship on social media?

MB: With “Undressed soul”, which is a separate project from my other works, I wanted a protected space where I could explore nude photography. The name of the project alone hints at its intimate and deep intent. It was only when I began taking the photographs that I realized just how much politics there were behind what I wanted to convey. For me, nude photography is, first and foremost, freedom–in a world where we are constantly being observed and judged, it seems liberating to be able to show ourselves naked. This project, therefore, stems from a reflection on the body, especially the female body, which becomes a means of political liberation and self-determination through images.

I strongly believe in the power of representation as a political act of reclaiming bodies and their freedom. In my opinion, female nudity creates divergence because we live in a patriarchal world where women are mostly seen as objects, not active subjects, and others like to hold power of decisions over their bodies, even if only in their judgement. I’m convinced that if we could be free from the judging male gaze, we would feel freer to express ourselves with our bodies and the choices that affect them. Regarding censorship on social media, I think the same argument as above applies, since social media reflects society; what’s more, as the algorithm often decides what to censor, there’s no distinction between pornographic content and content depicting artistic nudity.

DD: As a woman and a photographer, what do you think is the most genuine way to represent women and our relationship with our bodies?

MB: I think the truest, most honest way to represent women and their relationship with their bodies is by actively listening to what they want to express and the motivations behind these choices. I don’t like to impose scenarios or sets. I want the shoot to be a shared work between me and the models and to establish a relationship of mutual trust; in fact, I mainly shoot my friends. I’m super stimulated by other people’s ideas, and I feel that for this specific type of photo, you need a human connection outside of the work connection. I’d like to be able to portray women of different ages, bodies, and characteristics because it’s essential to represent women’s diversity. Too often have I felt uncomfortable with my body because what I saw represented on television or social media was the result of a sick, unreal standard. I wish women had more opportunities to hear and support one another. Our sisterhood and empathy unites us all.

Photos by Maria Flaminia Bari

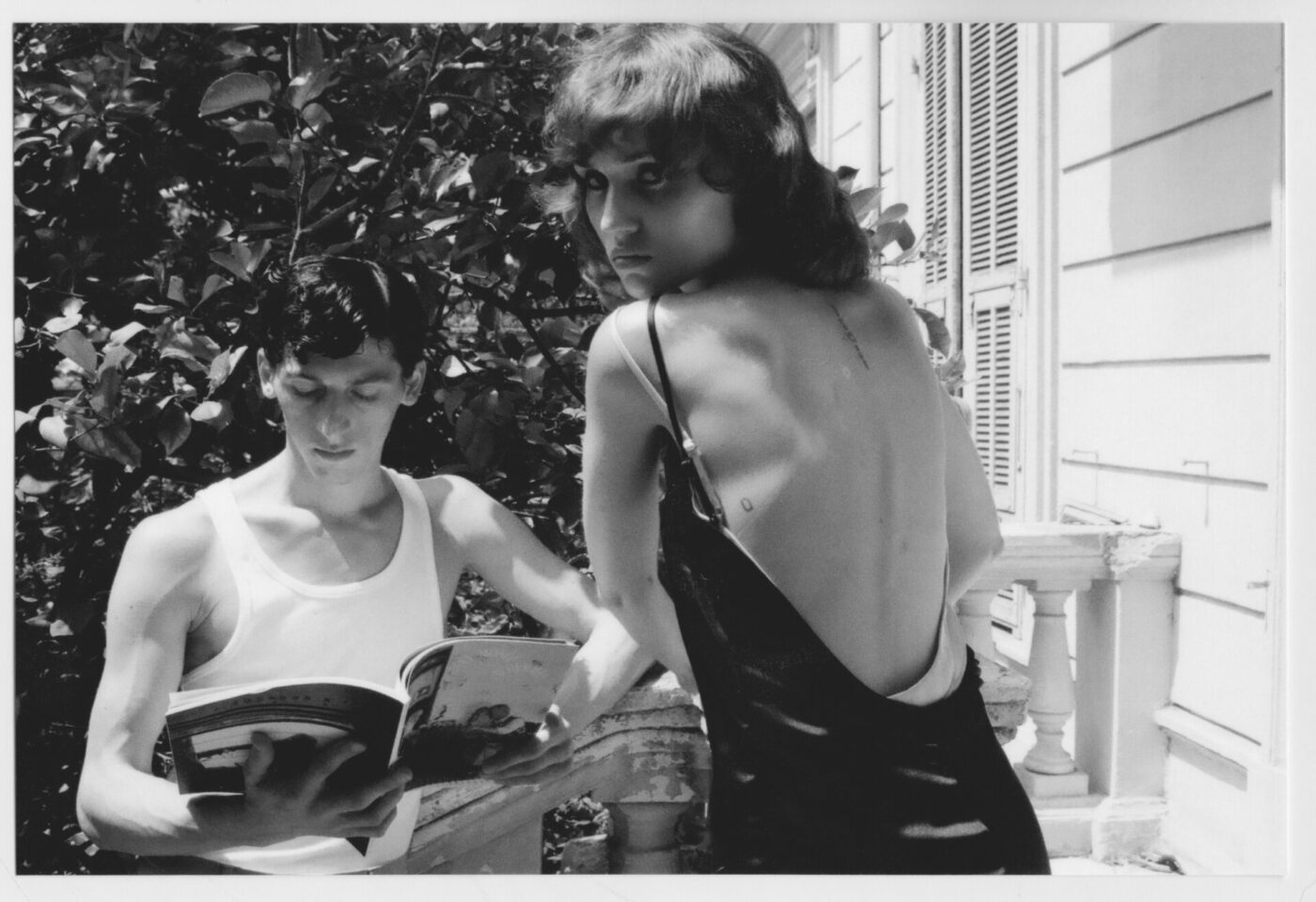

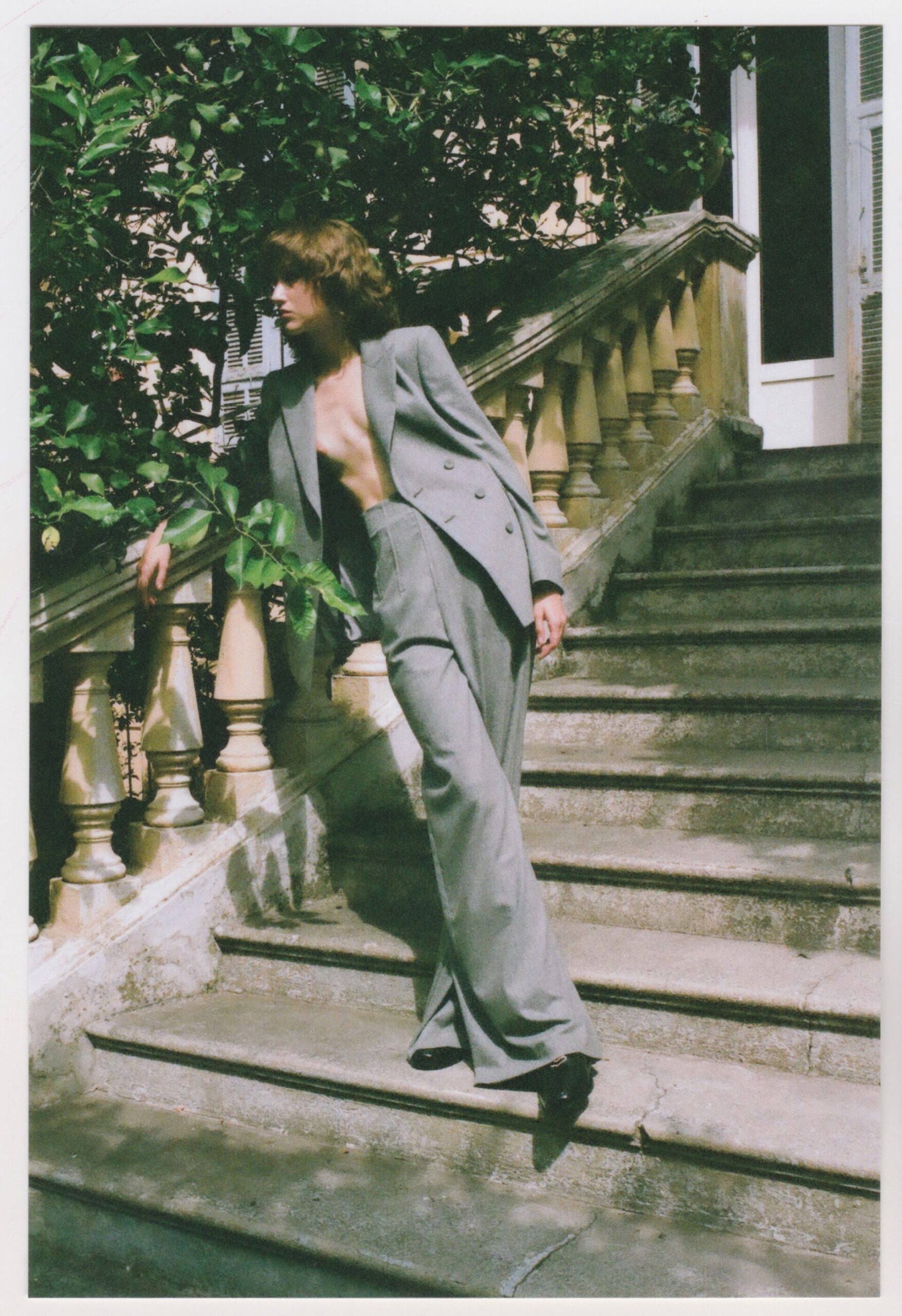

LUISA PAGANI

Born in Agordo in Belluno, Luisa Pagani is a film director, photographer, and contributor of Artribune. She attended the Luchino Visconti School of Cinema in Milan, and began her career in the world of fashion and art media in 2015. She is currently based in both Milan and Paris, working both as a photographer and in video commercial work for fashion brands, editorials, and magazines.

DD: What I think unites your vision is a sort of retro, melancholic aura, which you define as “decadent”. Plus, you have a great passion for cinema, and your works reflect its aesthetics. How do these two elements tie in: your vision and the images/films you draw inspiration from?

LP: Cinema led me to discover photography; films inspire me and remind me of what we can create. Cinema is a great escape into something better than the present; both a stimulus and a point of arrival. Truffaut, Varda, and Godard’s Le Mépris and Bande à part; Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, 8 1/2, and Giulietta Degli Spiriti; and Antonioni’s trilogy including La Notte… These unparalleled dreamers created worlds that weren’t perfect, but instead magnetic, charismatic, complex, thoughtful, and decadent.

I’m attracted to subjects and places by things that seem unrevealed, complex, and unsharp, almost from another time–although there’s certainly something interesting about photographing the age we’re in. Not getting lost and staying connected to ourselves is the challenge that makes the everyday intriguing.

DD: As a woman and a photographer, what do you think is the most genuine way to represent women and our relationship with our bodies?

LP: I believe that true authenticity only emerges when we’re comfortable with those around us and with ourselves. It can make all the difference. Women, in my opinion, should think of themselves much less aesthetically, although this is, of course, the way we’re perceived by the world. Aesthetics and beauty are the sugar of life, but they should be a consequence of well-being, not vice versa. Our serene appearance and manner can be a mirror of what is going on in our heads. For me, photography therefore has no power; instead, it can choose and give importance to something healthy, energetic, and impactful for that moment or place. Life offers fluctuating paths, and representing moments that aren’t necessarily happy is certainly another singular and interesting challenge. Photography, for me, should give a respectful look at the subject, putting her at ease and bringing out what she has to say, without saying it.

Photos by Luisa Pagani

MARIA GIOVANNA GIUGLIANO

In 2023, Milan native Maria Giovanna Giugliano won the MIA Irinox Save the Food award for her project “Ordinary Pleasures”, with a unanimous jury who applauded her ability to “shed light on the strong relationship that people have with food through their senses.” Most of her pieces tell a similar story of the bond between humans and nature through food, drawing on what she learned while studying in both Milan and New York City.

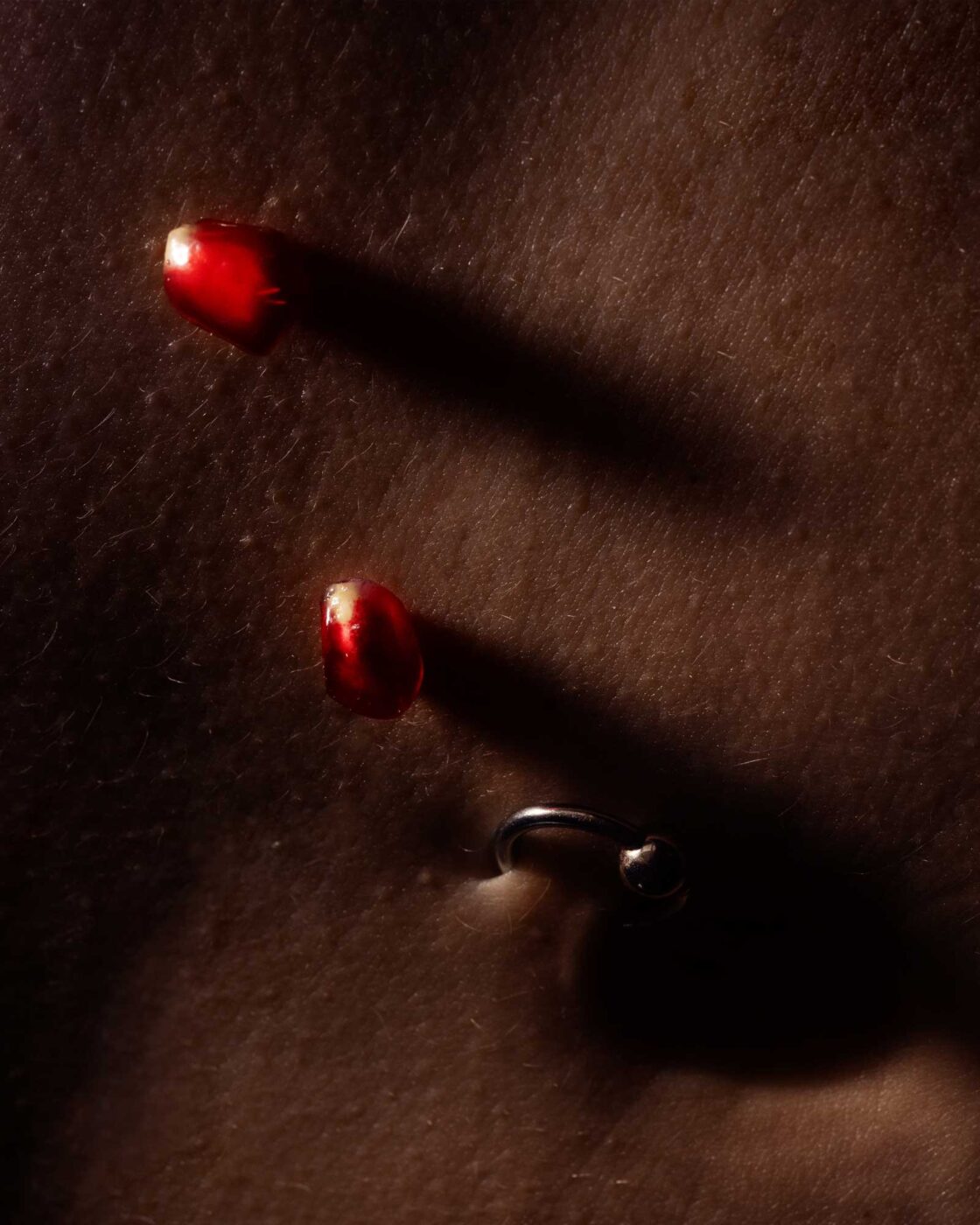

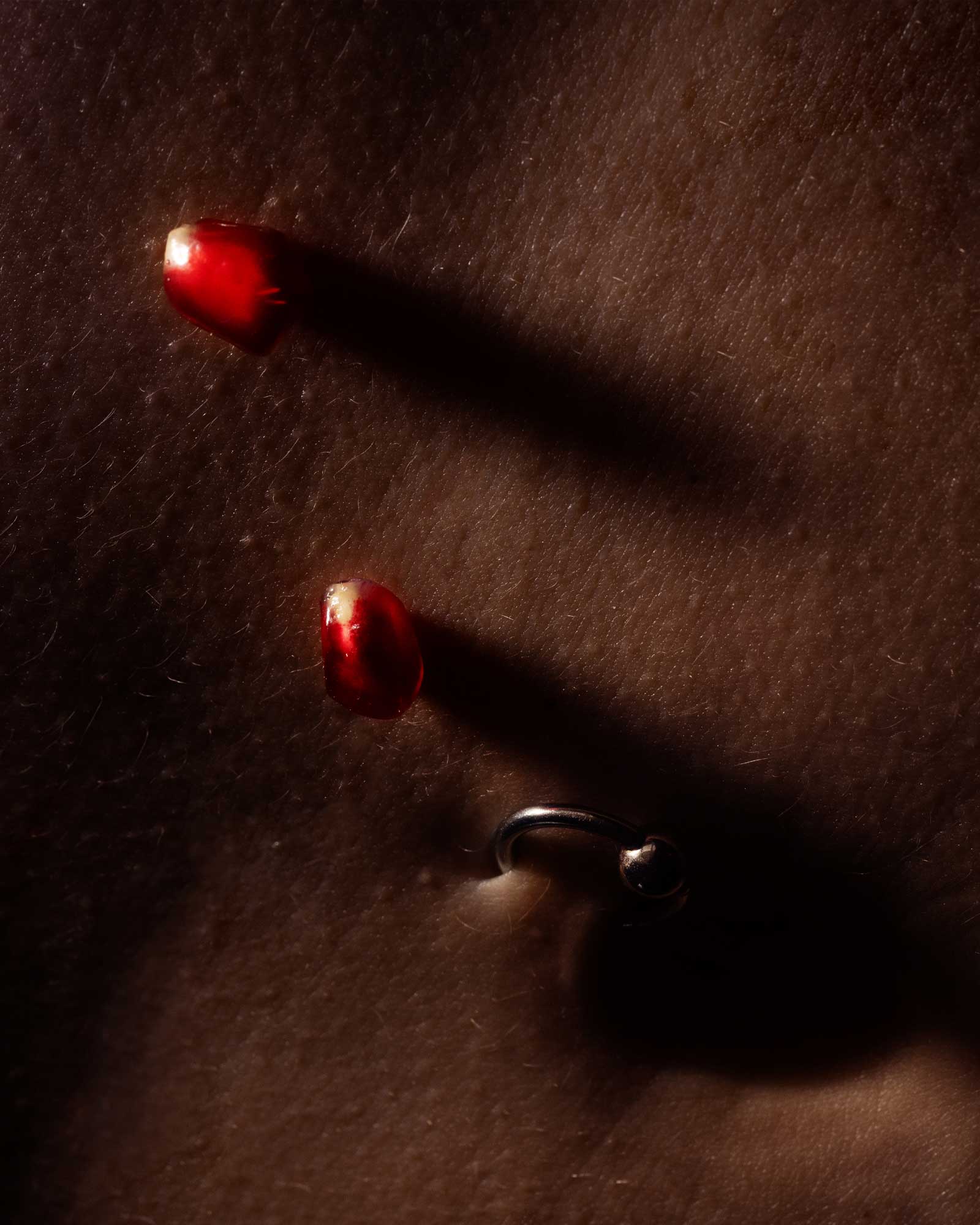

DD: Your photography is a visceral, passionate look at food and how it relates to the body, with closeups on textures and lips, fingers, tongue–an almost erotic tale. Why this close, surgical look? How does food relate to the female body?

MG: Ambitious photography appropriates moments. It collects tales imbued with light, outlines places, evokes flavors and specific scents. This is how I narrate food, by engaging all the senses. It fascinates me how an external entity can be joined to our flesh and sustain it.

The female body, holder of the omnipotence to bestow life, is sinuous natural art. Countless narratives juxtapose the woman’s body with food, exaggerating the appeal of any given product. A woman’s body is a living element, experiencing and perceiving. She daily absorbs the natural world through breath and nourishment. These expressions of life are sensual… or is it me who sees sensuality in being alive?

DD: As a woman and a photographer, what do you think is the most genuine way to represent women and our relationship with our bodies?

MG: I’m enraptured by the wonder of our unrepeatability: sculptural visions, divine architectures. I like to discover each woman’s special forms and how she embraces them, portraying each without dramatization, connecting her magnificent body to an entire ecosystem. A woman represented without any filter, without any modesty, which is itself the cause of malice. To visually portray a woman’s body is to describe an intrinsic well-being, the pride of being, regardless of social considerations and their projections. I think of my mother, the bath foam caressing her smooth, perfumed skin. Women in purity, far from stereotypes.

Photos by Maria Giovanna Giuliano

CLAUDIA GIGLIO

Born in Naples and based in Milan, Claudia Giglio graduated in Scenography and Photography in the field of Photojournalism. Between Rome and Naples, she’s worked in photography and photo post-production in various fields: news, advertising, fashion, still-life, stage photography, events. In 2016, together with Lucia Dovere (who’s also interviewed here), she founded Mill Photo Studio, which photographs events and destination weddings.

DD: I’ve noticed that often, even in the photographs that you and your partner Lucia Dovere take for “Mill Photo Studio”, the protagonists are not whole bodies or scenes, but close-ups, as if you wanted to enclose everything there is to say in a small space. How do you express femininity in each detail?

CG: When I think of femininity, I can’t help but think of my ideals of beauty which, besides aesthetics, encompasses authenticity, justice, grace, and tenderness. In weddings, women are the stars, but they tend to hide under the blankets of make-up, poses, dresses, and jewelry, in a race to win the approval of others and to keep up with the fashions of the moment. The worst thing about wedding photography is the wedding photography itself, which is why Lucia Dovere, a photographer friend and now business partner, and I created “Mill Photo Studio”.

In my case, photographing these details allows me to look beyond the big picture and bring out the authenticity and truth of the protagonists. Weddings can be a lying fairytale, and it’s important for me to handle them with care, de-emphasizing the staging and giving the moments as much honesty as possible. I’m tired of the usual traditional iconography that depicts brides as madonnas. To say that every woman on that day is unique is just marketing; in reality, these brides have never looked so much alike.

It’s in this “visual fatigue” of mine that details have come to my rescue. You don’t have to conform. We’re made to believe that beauty equals trendy, since that’s what keeps contemporary dystopian society flourishing. It’s a big lie. I find beauty in the truth, in the nuances, in the small pieces that open your gaze to social, anthropological, cultural, and political perspectives. So, I narrow my gaze in hopes of describing the universal nature of women. The world belongs to the curious; curiosity overcomes flatness and homologation. The trick is to remain oneself, and when I take my pictures I am myself.

Claudia chose to answer the second question together with her partner, Lucia. Find their joint answers below.

Photos by Claudia Giglio

LUCIA DOVERE

Born in Naples, Lucia Dovere poured herself into the study of and work in art history. But she began picking up her camera after becoming a mother, discovering the tool that ultimately saved herself from postpartum depression. Her shots from the “Corpo Madre” (“Mother Body”) photo project explore themes of motherhood with photos of women’s and mother’s bodies. And since 2015, she’s been photographing weddings with her friend, Claudia Giglio, as part of their Mill Studio Photo.

DD: Your photographs focus on motherhood, and you run a project and a workshop called “Corpo Madre” (“Mother Body”). I’d love to discuss how you view the relationship among nudity, motherhood, and female bodies.

LD: Drawing from who I was as a woman before being a mother, I like to investigate the relational and bodily space between mother and fighter: the great fullness, the immense emptiness, the hidden and torn freedom. Though I often felt like I was gasping for breath, maternity was what I wanted. As a mother, I experienced a range of loneliness and relational dependence; watching my body transform was simultaneously powerful and frightening.

During the pandemic, the “Mama gaze” was born: a worldwide visual movement in which the woman/mother is photographed in her truth. Through my photography, I aim to capture the truth of small moments that feel like miracles. In my project “Corpo Madre”, I explore motherhood through the image of bodies in transformation between strength and fragility, isolation and completeness: wounds and cuts, stretch marks and swollen veins, pulled nipples and deformed bellies; arms that give hugs that are indispensable for living, hands that clasp so as not to fall. Bodily dependence comes before mental dependence. It’s life or death. Lives that are born together again, both devouring and nourishing each other.

This “private zone” has become my natural territory of exploration: cruel and sweet. The mothers I photograph display a courage I rarely see elsewhere. We so often fail to care for these moms, instead often taking their care for children for granted. But I’m interested in knowing how women really are, giving them space to share both joy and any psycho-emotional discomfort, which they might not have opportunity to do elsewhere. During my photo sessions, I jot down the words that they speak with relief, and then look for that feeling in the photos. I believe that the “predisposition” to motherhood is influenced by society, culture, and the environment in which we live, not from a divine “maternal instinct”. This is why women need to be seen for how they really feel. When you feel seen, you feel a little less alone.

DD: As a woman and a photographer, what do you think is the most genuine way to represent women and our relationship with our bodies?

CG: Truthfully, women have to stop being what others want them to be and claim the right to be free, whole, and without fear. Our society is made up of people who need to censor themselves and others to feel at peace. We have to cover ourselves with asterisks and pixels on our nipples, even when representing paintings and sculptures. The natural is as obscene as it is true. The world is changing before our eyes–but what if we’re just creating the very thing that they want to erase? I don’t have an answer, but I believe that while impositions are sometimes necessary, they’re not always effective—especially in a society that’s clearly in decline.

LD: Together with Claudia, we most often photograph women that we don’t know, sharing intense and intimate moments. We never ask our subjects to smile, but to be however they want. What emerges is a struggle to break free from outdated stereotypes. We’re always surprised by these women’s need for approval from their friends and male partners. But it’s exactly these men who don’t approve of intimate photos, those images that capture the powerful feminine essence. In our editorial work “Trama”, we highlighted how women are often portrayed as passive figures, mannequins. But we need true emancipation; the chaste veil and princess dress no longer fit.

We seek awareness in the male perspective because their emotions matter to us. But awareness—not submission—must be nurtured, even through internal struggles. Until we move beyond traditional roles as partners or spouses and help men confront their fear of vulnerability, the portrayal of our bodies will remain censored and devoid of true beauty. There is no beauty in censorship; there is no beauty without truth.

These interviews have been translated from Italian and edited for length and clarity.

Photos by Lucia Dovere