When the clock struck midnight on March 8th, 1931, there was no sign that this date would mark more than just a new day in Turin. The city slept, unaware of what was unfolding behind the walls of Via Vanchiglia number 2. There, just steps away from Piazza Vittorio Veneto, the Taverna del Santopalato was about to open—the first Futurist restaurant in Italy.

A date that, as announced, “will remain etched in the history of culinary art just as indelibly as the dates of the discovery of America are fixed in the history of the world.”

Too presumptuous for a restaurant? Well, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was never one for modest ideas.

Futurism, the avant-garde movement he founded in 1909, proclaimed an absolute rejection of tradition and called for a new world of speed and modernity. In light of this vision, no city was better suited than Turin to lead their revolution. Already established as Italy’s first industrial city and dubbed “Futuropoli” by the Futurists, it was destined, in their eyes, to become “the cradle of a new Italian Risorgimento—this time gastronomic.”

First pages of Marinetti's Manifesto of Futurist Cuisine

Their radical vision aimed to revolutionize not just the arts but every aspect of life. And cuisine, anchored in a past preserved in every recipe and thus the antithesis of innovation, would not escape their offensive. So, on that fateful March night, the stakes were high. The Futurists set out with the “lofty, noble, and useful goal of radically transforming our race’s diet—fortifying it, dynamizing it, and spiritualizing it with entirely new foods.”

Fourteen such dishes would be served to 30 distinguished guests, including Futurists from across Italy, journalists, and “several beautiful ladies.” All were greeted by Fillìa—pseudonym of artist Luigi Colombo and the movement’s deputy secretary—who acted as master of ceremonies, guiding the diners through each course.

And yes, instructions were necessary to decipher the dishes with evocative names like Antipasto intuitivo (Intuitive Appetizer), baffling ones like Pollofiat (Chickenfiat), or intriguing ones like Carneplastico (Plastic Meat) and Aerovivanda (Airfood, tactile, with sounds and smells).

The appetizer, the only one of the 14 created by a woman—Mrs. Colombo-Fillìa—was far from living up to its promise of being intuitive. It consisted of an orange stuffed with cold cuts and peppers, with hidden notes bearing phrases like, “Doctors, pharmacists, and undertakers will be unemployed with Futurist cuisine.”

A critic called the dish “exquisite,” while Pollofiat left a less favorable impression on journalist Clara Grifoni: “Tonight I’ve endured my third gastric cleansing; the ball bearings of the Chickenfiat absolutely refuse to leave my intestines.” Perhaps because those “bearings” were made of mild steel? Who knows.

But it was Aerovivanda and Carneplastico, both conceived by Fillìa, that became the most iconic creations of Futurist cuisine. With its phallic aesthetic, Carneplastico might be considered a work of engineering: a large, cylindrical roast veal meatball, filled with 11 types of cooked vegetables, covered in honey, and supported by a base ring of sausages resting on three golden spheres of chicken meat.

Though its structure may seem intimidating, preparing Carneplastico is surprisingly feasible. Aerovivanda, on the other hand, requires careful focus. A small slip in coordination could have disastrous consequences.

On the plate, Aerovivanda presented a quarter of fennel, an olive, and a candied fruit, accompanied by a tray holding pieces of velvet, satin, and sandpaper. First, with the right hand, you eat the olive, then the candied fruit, and finally the fennel, while the left hand caresses the different materials. And the experience didn’t stop there: Wagner played from a hidden source as the waiter sprayed perfume around the room.

The four-hour dinner may not always have been delicious, but it was certainly never boring—true to the Futurist philosophy of “renewing the excitement of eating, inventing foods that bring joy and optimism, and infinitely multiplying the joy of living.”

What else could one expect from an evening orchestrated by the explosive duo of Marinetti—dubbed “Europe’s caffeine”—and Fillìa, nicknamed “nitroglycerin bombard”?

Like this very first one, future Futurist banquets represented a total artistic experience, in which the transgression of all rules of conviviality was integral to their provocative nature. Every sense was designed to be engaged: music set the rhythm of the meal, aromas were strategically diffused in the air to enhance the perception of flavors, and the use of cutlery was forbidden, requiring diners to eat with their hands or interact with tactile elements as part of the culinary experience.

The provocations extended to taste as well. The Futurists openly challenged culinary conventions by proposing bold combinations and unusual pairings, offering dishes that broke the rigid distinctions between sweet and savory or between meat and fish.

While the movement more or less failed in its goals to forever change Italian cuisine, many of its insights were echoed decades later in new gastronomic trends–perhaps first in nouvelle cuisine, and later in Ferrán Adrià’s molecular gastronomy.

But, truth is, their sensory and symbolic revolution was short-lived: the Taverna Santopalato was forced to close after only a few years, unable to overcome financial difficulties. Though the success of the restaurant was never their primary concern. Fillìa made it clear that its opening was an artistic experiment—a practical application of a theory published just months earlier, in December 1930, in Turin’s Gazzetta del Popolo: the “Manifesto of Futurist Cuisine”.

This manifesto, both controversial and highly entertaining, launched a direct attack on an almost sacred enemy: pasta. Abolishing this “absurd Italian gastronomic religion” topped the list of 11 points in the manifesto, and it was undoubtedly the one that caused the most uproar among the passatisti—defenders of tradition.

For Marinetti, “one thinks, dreams, and acts according to what one eats and drinks.” And as the good Fascist he was, he believed the modernity-driven uomo nuovo (new man) could not be one dulled by carbohydrates, which made people “skeptical, sluggish, and pessimistic.” No, Italian bodies needed to be agile, light, and virile—ready for combat and suited to “an increasingly aerial and fast-paced life.”

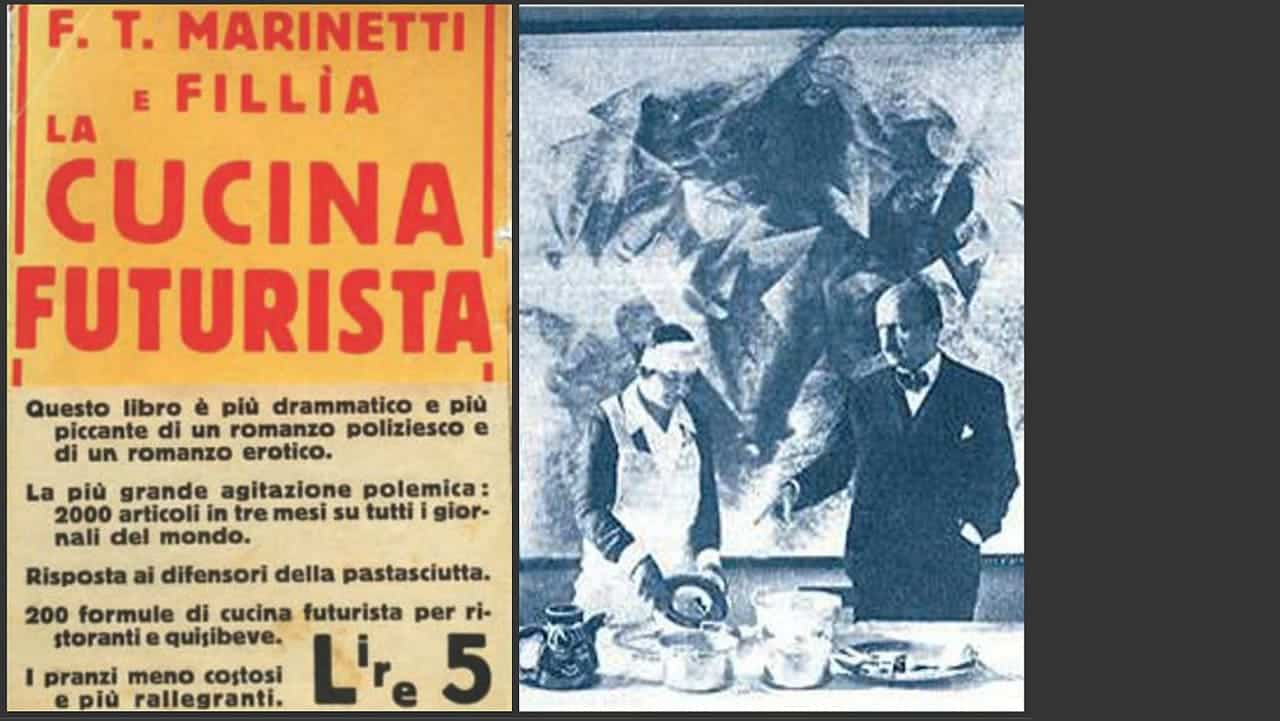

Marinetti's Manifesto of Futurist Cuisine

The Manifesto of Futurist Cuisine (unsurprisingly) sparked an international scandal. The Italian and foreign press echoed this radical proposal, igniting heated debates between passatisti and Futurists. To ensure the impact wouldn’t dissipate into newspaper pages, Marinetti and Fillìa compiled their principles into La cucina futurista, published a year after Santopalato opened.

A book, as its dust jacket promised, “more dramatic and spicy than a detective novel or an erotic novel.”

In addition to collecting their gastronomic theories, it features 200 recipes for everyone to eat futuristically.

So, if you think it’s time for you to “abolish the mediocratic routine of everyday pleasures,” here are some dishes to launch your personal gastronomic revolution:

Aeroporto piccante (Spicy Airport)

Formula by the Futurist Aeropainter Caviglioni

A bed of Russian salad with mayonnaise, covered in green. Around it, varied medallions made of sandwiches stuffed with orange, egg whites, and mixed fruit. Use red-dyed butter and anchovies or sardines to create airplane shapes on the green field.

Terra di Pozzuoli e verde veronese (Pozzuoli Earth and Verona Green)

Formula by the Futurist Farfa, Poet and National Record Holder

Candied citrons stuffed with fried, minced cuttlefish. Chew them thoroughly as if they were anti-Futurist critics.

Placafame (Hungerstopper)

Formula by Futurist Giachino, owner of Santopalato

On a large slice of ham, place raw salami, pickles, olives, tuna, pickled mushrooms, and artichokes. Bring the two ends of the ham together and fasten it closed with anchovy fillets, pineapple slices, and butter.

Mammelle italiane al sole (Italian Breasts in the Sun)

Formula by Futurist Aeropainter Marisa Mori

Create two hemispheres filled with almond paste. Place a fresh strawberry in the center of each. Then pour zabaglione and dollops of whipped cream onto the tray. Sprinkle with hot pepper and garnish with red chili peppers.