Wild, remote, unspoiled. These are the adjectives that surface, on cue, whenever Filicudi—one of the smallest of the Aeolian Islands—comes up. Words that, rather than describe, flatten the more than 700 meters of this volcanic island north of Sicily, reducing it to a laminated postcard. And really—who would ever call their own home “wild”?

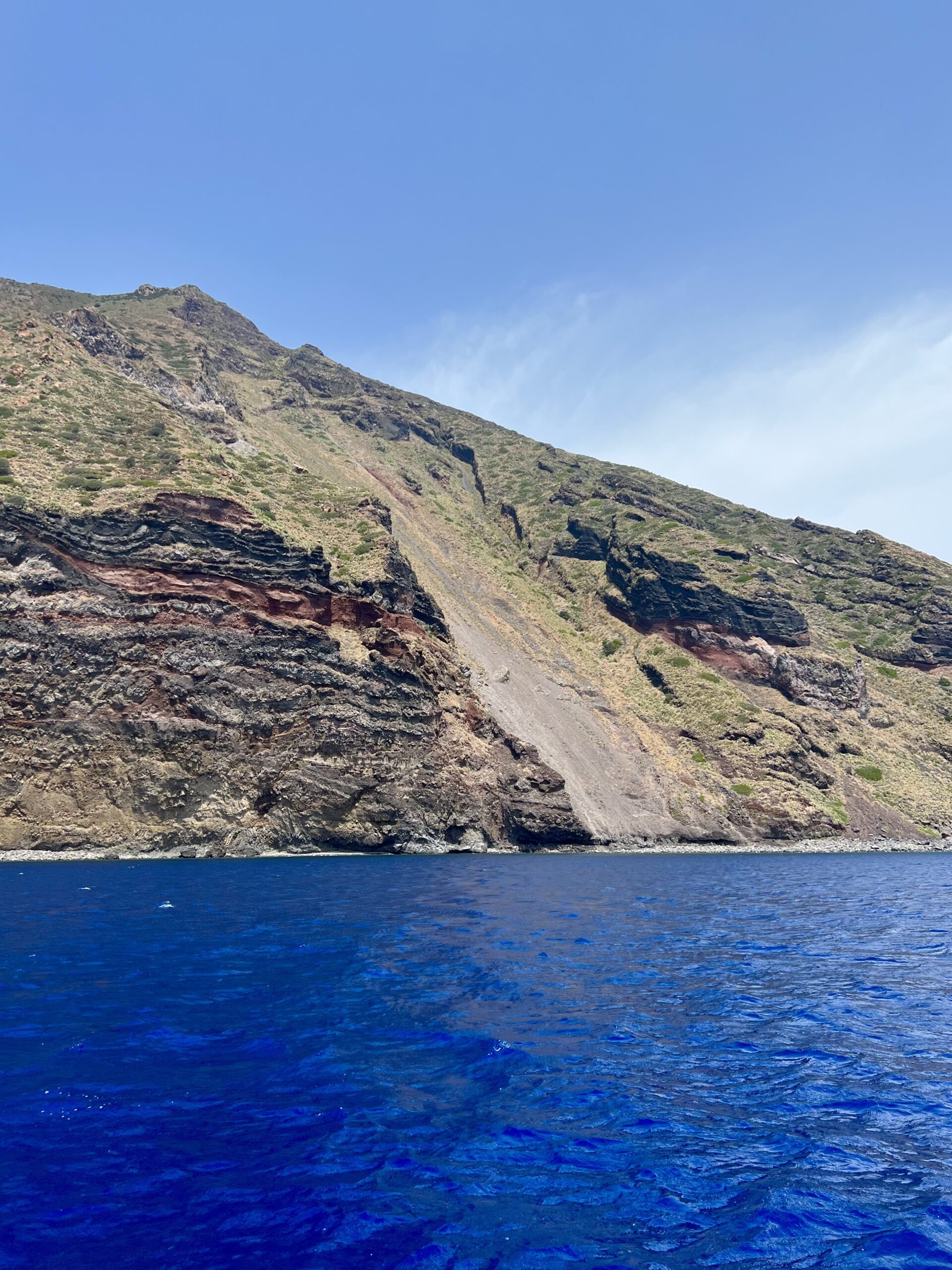

The pointed island we see today—the first to emerge, 600,000 years ago, from the depths of the Tyrrhenian Sea—is the summit of a volcano that descends for 1,600 meters, a depth that doubles its height. A submerged, invisible body that nonetheless supports everything visible above. So it is with Filicudi’s history: we know the part that emerges—gorgeous sunsets, fabulous vacations—but those who nourish and sustain it remain offstage. Often behind closed doors.

Giusi Murabito knocked on those doors.

Murabito, a Catania native who moved to Filicudi 10 years ago, sought to meet the island’s true custodians, approaching its women—both natives and newcomers—with one request: to share a recipe. Twenty women invited her into their kitchens where an everyday, feminine, and often invisible knowledge resides—one that explains the island’s identity better than any monument or landscape; an identity built on ingenuity, emigration, resistance.

Some shared hesitantly, some enthusiastically—and some with a pinch of competition: “Have you tasted her pasta with potatoes? Then you have to try the one with fava beans my sister makes!” Others shared their stories with a sense of urgency, aware that this knowledge could easily stay locked inside the home—or, as one woman put it, “because otherwise they’ll be forgotten.”

Murabito, however, received far more than a list of ingredients. Each recipe became a kind of emotional cartography, mapping the island through 20 different ways of living on it. Every dish carried stories of departure and return, of scarcity and longing, of solitude and community—reminders that cooking here is never just a domestic chore.

And so Murabito gathered both the stories and the dishes in a book, titled La cucina delle donne. Storie e ricette di Filicudi. The idea took root during the walks and treks she leads across the island. One traveler, Giulia Piepoli, moved by the way Murabito narrated its stories, asked: “Why don’t you write a book?” Murabito knew immediately she didn’t want to write it alone. “This book is a form of gratitude to the women who taught me how to live on the island. They are my teachers,” she tells me.

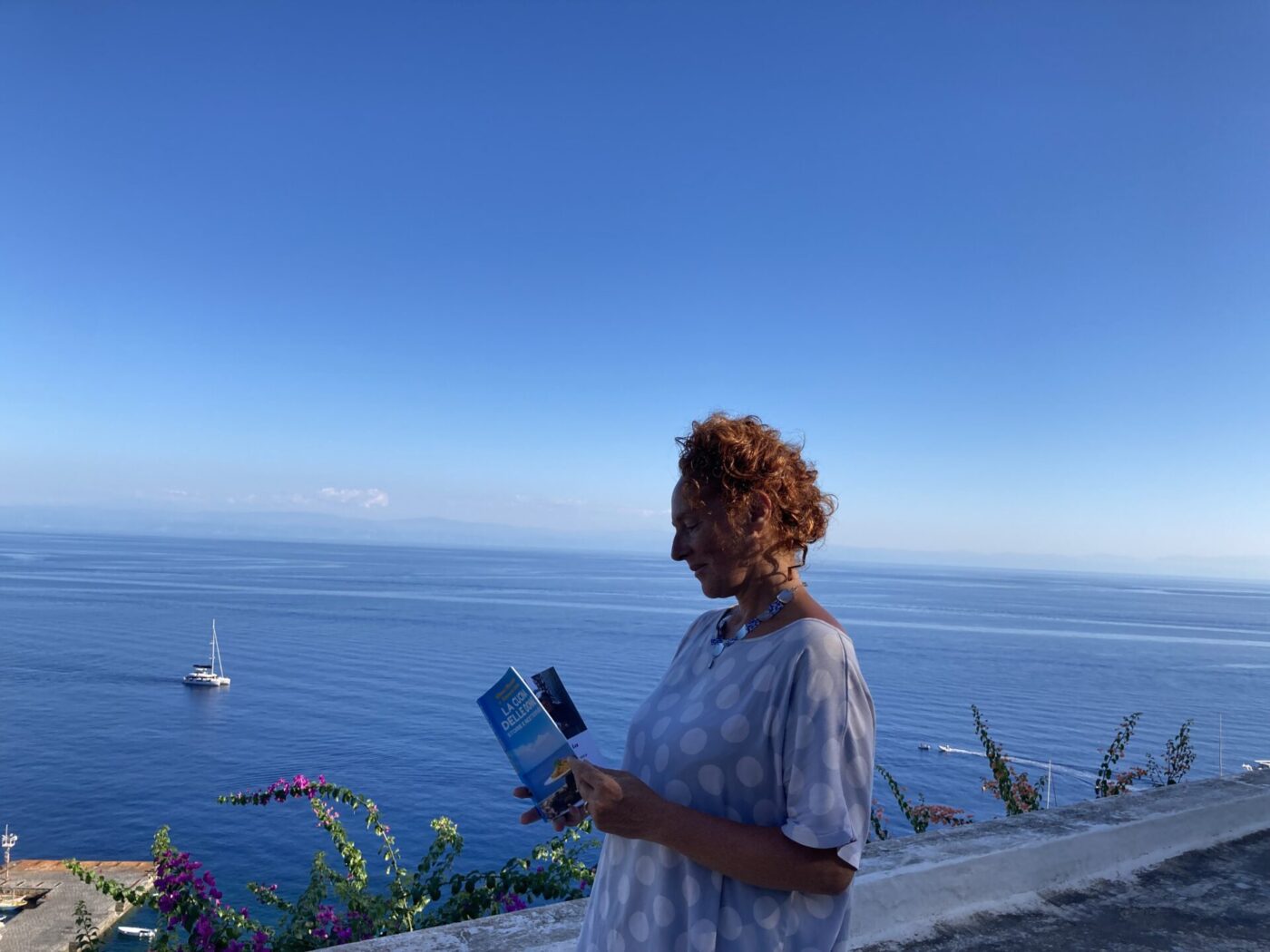

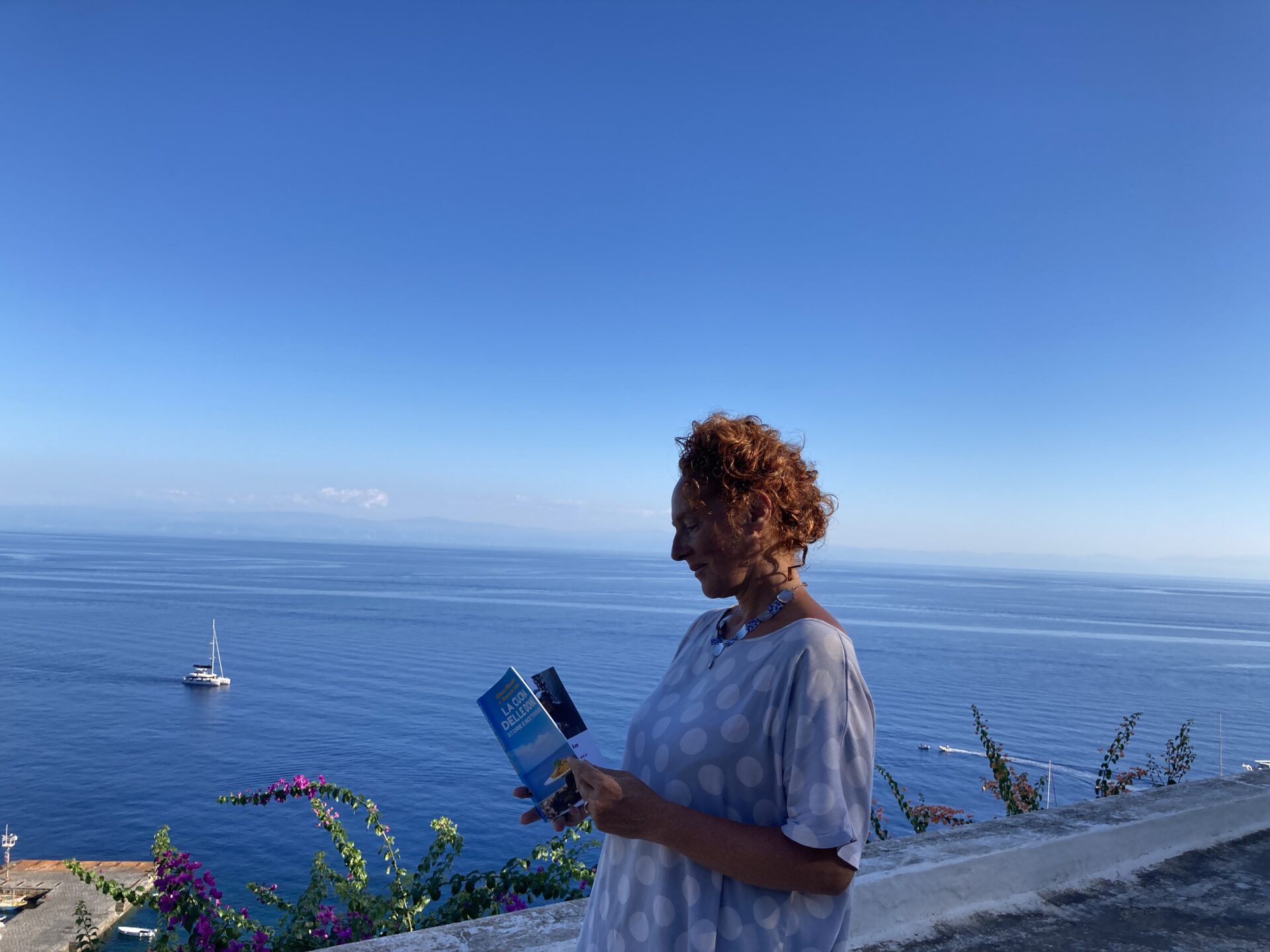

Giusi Murabito; Photo by Maura Sánchez Escudero

Maria Mangano was her first teacher. “When I still didn’t live here permanently,” Murabito tells me, “I would come back in winter and she rented me a little house. She taught me the mule tracks, the wild greens, and then we cooked.”

Wild vegetables and herbs are among the island’s greatest riches. Gathered in winter and preserved for later, they’ve long held pride of place in Filicudi’s cooking. In La cucina delle donne. Storie e ricette di Filicudi, Angela Bartolone sautés them with cherry tomatoes and potatoes. Lucia and Claudia Bonica make wild fennel fritters (wild fennel never runs out in Filicudi). And then there are lesser-known varieties, cardella (wild chicory), rapuddi (wild turnup tops), guide (wild chard), lazzini (wild arugula)—plants that the women know how to both recognize and use. “The island is generous and the raw material is of extraordinary goodness,” Murabito explains. But generous does not mean easy: “Only what knows how to live without water grows here.”

Aglioporro in prep; Photo by Giusi Murabito

Few vegetables capture Filicudi’s kitchen—and its challenges—better than aglioporro, the island’s most emblematic wild leek. It grows in abundance at Siccagni, a rugged district that plunges straight into the sea, and gathering it is no simple task. Murabito and her partner, fisherman Antonello Bonica, reach it by boat: he scrambles up the rocks, fills sack after sack, and tosses them down to her on the deck. She spends days cleaning the haul before freezing it, ensuring she can make aglioporro fritters for guests year-round—and for us the very next day.

This bond between land and sea defines much of the island’s culinary culture, as does the art of preservation. Margherita Zingales experiments with sweet and savory preserves and obsessively perfects gelo di limone. One look at her pantry tells you everything you need to know: every shelf brims with jars—jams, vegetables submerged in oil, liqueurs—evidence of a passion that knows no season.

Margherita Zingales' gelo di limone; Photo by Maura Sánchez Escudero

Like Murabito, Margherita Zingales is from Catania, and her bond with Filicudi began at six months old, on her first trip here with her family. She kept returning until eventually deciding to stay. Zingales had no doubts about the recipe she wanted to share—spaghetti with cuttlefish ink—but with an unexpected addition: carrot. It’s a tweak that caused a few gasps. “A sacrilege,” she adds, amused.

Even bread is made to last here. Ada Foti, from Lipari, who moved to Filicudi for love in the mid-1980s, recalls baking it once a week in the wood-fired oven. The first day you ate it fresh; the others, caliatu—that is, twice-baked. Pane caliatu kept for up to a month, stored in the same oven it was baked in. Going to fetch it was an adventure. “After a few days, when we needed it, my brother and I would slip inside,” remembers Annuzza Cappadona, born in Filicudi to Filicudi parents. “It felt like a game: going into the oven and coming out with the bread in our hands, as if it were a treasure,” she tells me, laughing from her veranda, where bunches of onions hang and you can glimpse the green tufts of caper leaves in her garden.

Freshly harvested aglioporro; Photo by Giusi Murabito

“Filicudi teaches waiting,” says Murabito. “Waiting for the rain to stop, for the wind to change, for the sea to calm. All you can do is wait. And live with the fact that, simply, certain things just aren’t here.” This is especially true in winter, when the sea runs high. Small boats can’t leave the port, and the ferry from Milazzo never arrives. On those days, they’re stuck—and they need to get inventive.

Pisci d’ovu, one of the dishes Annuzza Cappadona chose to share, is the child of that spirit. It’s a fish without fish—made from eggs, breadcrumbs, parsley, and Parmigiano. An imaginative answer to scarcity, it’s a way of cooking that doesn’t just fill a void but bridges it with irony and creativity.

If we’re talking about real seafood on Filicudi, however, we talk about totani. Undisputed kings of the Aeolian table, they’re cooked, stewed, stuffed, grilled. Immacolata Lopes taught Murabito how to stew them with potatoes. “Even though,” says Antonello Bonica, with a touch of resignation, “you find fewer and fewer. Like octopus.” That evening we’ll taste them stuffed, cooked by Maria Russo at Il Boschetto—her restaurant—along with another of her specialties, pasta alla carrettiera.

Annuzza Cappadona at home; Photo by Maura Sánchez Escudero

“Andare a totani”—to go squid fishing—is a skill you have to master if you live in Filicudi. “You go at night, lower the line hundreds of meters, then you have to feel the strike, sense whether it’s taken the bait. And then you haul up, slowly, hoping the squid doesn’t slip free,” explains Bonica—a fisherman, and the son of fishermen—as we eat.

As in the rest of the Aeolian Islands, fishing in Filicudi was never solely men’s work. Women—and sometimes entire families—went out to sea to catch, depending on the season, orate, dentici, aragosta, parghi. (Something we know today thanks to the work of anthropologist Macrina Marilena Maffei—another story submerged within the archipelago.)

The strength of these women also surfaces in Cappadona’s memories. She recalls an episode from more than 40 years ago when, in the middle of a storm, she and her mother saved her father—who didn’t know how to swim. “My mother climbed onto the rock while I held on to her with one hand. A wave lifted him and he grabbed my arm. He was saved. The boat, meanwhile, was smashed to pieces,” she recalls.

It wasn’t the only time she saved her father. With him, danger had a habit of changing scenery.

The second rescue happened on land—or rather, underground. Filicudi people were never just farmers and fishers; they were also herders and hunters, and Cappadona’s father was no exception. “When my father went hunting, he burrowed in with the rabbits,” she says. “One day the dogs came back without him—which meant he was still underground. So we went looking for him with a hoe, following the dogs. We could hear him shouting from under the earth, ‘Help! Help!’ and he’d tell us what to do: ‘Dig like this, pull from there…’ Little by little, we pulled him out. We freed him many times.”

If squid is king of the sea dishes, coniglio selvatico (wild rabbit) is king of the land. Or it was. “Today finding one is rare and, when it happens, it’s a luxury. They’ve fallen ill,” Bonica tells me. A viral hemorrhagic disease, MEV, has decimated the local population, and he, along with a group of friends, is working to recreate a natural habitat to repopulate the mountain.

As with squid, there used to be far more ways to cook wild rabbit, above all the sweet-and-sour version made with vino cotto (“cooked wine”)—grapes boiled together with the ash of prickly-pear pads, then filtered several times, brought back to a boil, and finally left to rest for days. It was one of the first dishes Murabito tasted in Filicudi. “It drove me crazy,” she recalls. “The sweetness of the vino cotto, the almonds and pine nuts with onion and raisins—it felt like diving into a Bourbon feast, a taste of an ancient Sicily.”

We find vino cotto again in the island’s sweets—central to the two recipes shared by the youngest of the 20 women. In La cucina delle donne. Storie e ricette di Filicudi, Angelica Bonica proposes gigi, little balls of fried dough similar to struffoli. Corinna Rando, meanwhile, makes catanedde, ring-shaped pastries once prepared solely to test the sweetness of the vino cotto.

When it comes to dessert, Filicudi boasts an abundant repertoire: paste squadate, spicchitedda, nacatuli… Each of these cose duci—“sweet things”—is tied to religious or festive occasions. Cappadona explains that making them was a collective effort, with all the women gathering in one house and splitting the tasks. “There was the one who kneaded, the one who decorated, the one who put things in the oven,” Murabito recounts to me, elaborating that every sweet uses a different type of dough. “For this recipe you knead one way, for that one another. You have to see how they knead. Their hands look like ladles,” she explains.

Maria Russo at Boschetto; Photo by Maura Sánchez Escudero

These hands never needed scales or notebooks. “I’ve always cooked by eye; I’ve never measured anything,” Cappadona says. “All of Filicudi’s recipes live in my memory.” Converting a memory built on bodily knowledge into grams was the greatest challenge for Murabito, and for the women themselves.

In the garden at Il Boschetto, once dinner service ends, Maria Russo returns to the same point, explaining that the dough itself tells her whether it needs more flour or more eggs. From the next table, a woman leans over, drawn by our discussion and by Murabito’s book in our hands. She tells us she owns it too, in English. Her name is Maria Grazia Bonica; she’s from Australia, the daughter of Filicudi emigrants. She confides that she can’t manage to make sfinci di zucca. “My mother used to make them, but now she’s elderly—she remembers, and she doesn’t. I keep trying, but so often they just don’t come out right.”

And here, the crux of Murabito’s work reveals itself: memory is fragile. It takes only a single generation—one departure, or one failure to learn—for a chain of knowledge to break. In minutes, our conversation drifts from cooking by eye to the journey overseas, from the imprecision of measurements to the hollow space an island can leave behind.

Filicudi knows loss well. The story of Lucia Rando del Canale and Antonino Bonica, Maria Grazia Bonica’s parents, echoes that of thousands of islanders who, in the 1950s and ’60s, left Filicudi and the other Aeolian Islands—often on their own—to seek their fortunes in Australia. There, a community formed that today is three times larger than the population that remained in the archipelago. Not by chance, they call it the Eighth Island.

The reasons for the exodus were many: the collapse of subsistence agriculture, unemployment, an absent state, and the fallout of war. And it wasn’t the first wave. Already in the late 19th century, phylloxera had ravaged the Malvasia vineyards—especially on Salina—forcing many to leave.

The Filicudi people left with few material possessions but an immense cultural heritage. That knowledge found continuity through organizations like the Società Isole Eolie in Melbourne, which this year celebrates its centenary, networks of solidarity where generational bonds with the island are renewed.

“Cooking, for me, was a lesson in how and where my parents came from,” Bonica tells me. “We children of immigrants in Australia grew up on Filicudi cooking, and I still carry it on with my children.” In many cases, the dishes cooked in Australia hold true to the Filicudi kitchen as it was at the moment of departure—adapted, of course, to local ingredients—while on the island itself the recipes have evolved.

Prepping onions is a team effort; Photo by Giusi Murabito

Back on Filicudi, those who stayed began to cook for the foreign tourists arriving on the island in the 1960s. There were no restaurants yet, so visitors ate everyday dishes in private homes. “People simply went ‘to Signora Maria’s,’ ‘to Aunt Peppina’s,’ ‘to Nunziatina’s,’” Murabito tells me. From those domestic tables, and without fanfare, Filicudi’s restaurant scene was born.

These women—like Il Boschetto’s Maria Russo and Villa La Rosa’s Lucia D’Angelo and her daughter Adelaide Rando—launched the island’s first tourist businesses from their kitchens. For many, it was also the first time they earned their own income—won with their own hands. If we can speak of a Filicudi cuisine today, it is because a female lineage passed it on. In this way, Murabito’s book is not just a collection of recipes but an act rewriting of history, one that returns voice and dignity to the women who have sustained the island.

Alongside the women already mentioned, this circle includes Alessandra Li Donni, Maddalena Bonica, Marilena Taranto, Nunziatina Alice Gignina, Tindara Sarpi, Zin Mar Soe, and Concetta Taranto from Alicudi. Together, they restore women’s culinary culture to its rightful place in the island’s collective memory.

Because, in the end, is there really any cuisine that is not women’s cuisine?