I’ve always had one foot in two places–Italy and Russia–but I never imagined that I’d have to do the splits between them. During the pandemic, when the borders were closed, spending weekends in St. Petersburg satisfied my longing for Italy while I was 2,000 km away. Walking along the Venetian-like waterways and past large buildings colored like those of Portofino or Florence, I knew the city felt like “Little Europe”, as it’s called among the locals, but I had little awareness as to why. Before I started connecting conversations in passing, scattered facts from family, and endless Wikipedia scrolls, I never thought about who was behind the beauty of Russia’s largest monuments or who influenced Russia’s world-renowned composers. I’ll give you a hint: Italians.

Russia and Italy have been culturally intertwined since the reign of Ivan the Great in the 15th century, but it was during that of Peter the Great, from 1682 to 1725, that lasting links were established. It was a period of economic decline in Italy, when the wealthy patrons who funded the lavish Renaissance and Baroque eras couldn’t afford new domestic projects. Italy had the talent but lacked the resources; Russia had the resources but lacked the talent.

Realizing that his empire was isolated from the rest of Europe, Peter turned to his skilful neighbors. The first tsar to go on a Eurotrip (from 1697-98), Peter’s zealous determination and adoption of Europe’s then administrative systems, architecture, and other cultural aspects allowed Italy to leave a strong mark on Russia. In many ways, Italy’s diminished economic power became inversely related to the spread of its cultural influence–it was no longer the singular heart of European creativity, but a supplier of talent to the rest of the continent.

Peter’s great love affair with Italian art and architecture in the late 17th and early 18th centuries was just one part of a grand scheme to elevate his empire to the technological and cultural heights of Western Europe. But, more than a quest for modernization, it was a way to usher in a new era for Russia, swinging open the gates to international influence–a move so monumental that Russian history is often split into pre-Petrine and post-Petrine eras. By reshaping St. Petersburg via Italian architects and creatives, the tsar symbolically and practically opened a “Window to the West”–one that set the stage for musical and cinematic influence even centuries later, during the 19th and 20th centuries, when the curtain was indefinitely slammed shut. Italian culture managed to sweep under, an unexpected outlet that provided a stark contrast to the bleakness of daily life under communism. Here, three fields–architecture, music, and cinema–that Italy left its fingerprint on.

St. Petersburg, known as “Little Europe” amongst locals

ARCHITECTURE

Italians laid the bricks for much of Russia’s architecture–literally, for it was Bologna-born Aristotele Fioravanti who founded the first Italian-style brick mill in Moscow in the 15th century. Brought to Russia by Ivan the Great, Fioravanti completely renovated the Dormition Cathedral within Moscow’s Kremlin: gold domes, white bricks, and stunning interior art were just a few of the embellishments the Bolognese implemented, paving the way for a new style of architecture that blended Russian design with the Italian school.

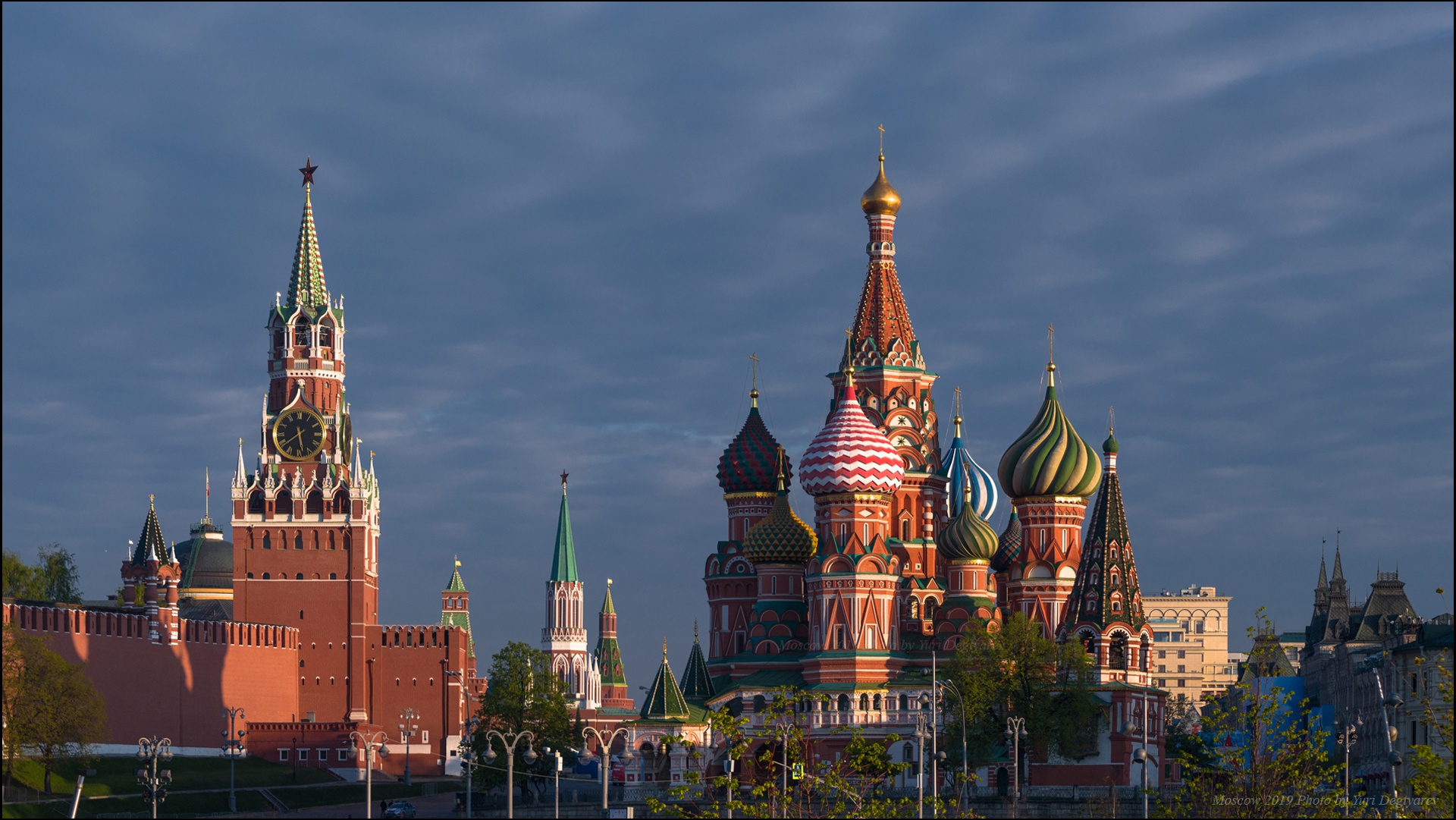

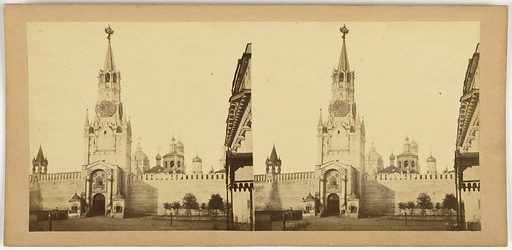

Ivan the Great clearly had a taste for the Italian way, later recruiting Swiss-born Italian architect Pietro Solari to work on other parts of the Kremlin. Solari took on six of the Kremlin’s towers, including the iconic, gold-star topped clock tower, the Spasskaya, which looks… exactly like that of Milan’s Castello Sforzesco? It’s no coincidence: Solari’s father, Guiniforte, was court architect to the Duke of Milan (and also happened to work on Milan’s Duomo).

Spasskaya Tower (on the left), Moscow

Spasskaya Tower, Moscow (circa 1850-1880)

However, hot on the heels of Ivan the Great’s reign was an economic crisis that meant Russia’s tsars ceased turning outwards for artistic and architectural inspiration. It seemed that Italian craftsmanship in Russia was destined to decline–until Peter the Great’s rise to power a century later. An opportune moment for Italy, which, once a vibrant hub of commerce, innovation, and artistic production, was now facing its own financial deterioration. The powerful city-states of Florence, Venice, and Rome that fueled Italy’s golden age were gradually overshadowed by the rising nations of Northern Europe–France, England, and the Netherlands–whose economies and political systems became the new centers of European power. Countries like France, Spain, and, again, Russia became fertile ground for Italian artists, sculptors, and architects–who, in an osmosis-like process, spread their culture and design across the continent.

Swiss-Italian architect Domenico Trezzini was the first of many to accept Russia’s newest job opportunity. Tasked with redrafting the messy city plan of St. Petersburg, Trezzini was offered a salary of 1,000 rubles by Peter the Great–a particularly luxe sum from a tsar who spent only 366 rubles on himself a year. The architect entirely transformed the grand waterfront entrance to the city, designing city-defining buildings like the Peter and Paul Cathedral, the Twelve Colleges, the Summer Palace, and Winter Palace of Peter the Great. His greatest influence in transforming the cityscape came by replacing wood with stone, crafting a foundation that would forever change St. Petersburg’s soul and helped earn the city its “Little Europe” moniker.

St. Petersburg; Photo by Maksim Rosliakov

MUSIC

A classic evening during my childhood consisted of my grandma and I watching ballet or listening to the music of the country’s all-star composers Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, and Tchaikovsky. Despite the all-Russian associations of the latter, he had a deep and lasting connection with Italy, both artistically and personally. Tchaikovsky first visited Italy in 1872 and returned several times throughout his life, finding inspiration for several of his works, including the “Capriccio Italien” (1880), a lively orchestral piece that features a woodwind-introduced tarantella linked to the Southern Italian folk tune “Ciccuzza”. During his time in the bel paese, particularly in cities like Rome and Florence, the Romantic composer also created portions of major works, such as his opera The Queen of Spades. For Tchaikovsky, Italy was a place of creative freedom and emotional respite, a welcome harbor from the tumultuous existence lived in his native country. “I have been working successfully over the recent days, and I have already prepared in rough an Italian Fantasia on folk themes, which it seems to me, might be predicted to have a good future. It will be effective, thanks to its delightful tunes, some of which I chose from collections, and some of which I heard myself on the streets,” he wrote to his friend Nadezhda von Meck in 1880.

Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo performing Tchaikovsky's "Nutcracker" (1940)

Italian tunes would also reach the country some 70 years later, during the cultural influx known as “Khrushchev’s Thaw”, the period of political and cultural relaxation following Stalin’s reign during the 1950s and ‘60s. As I’d flip through my grandmother’s vinyl collections or queue songs for her from Spotify, it was clear she knew Raffaella Carrà and Ricchi e Poveri as well as she did Tchaikovsky. When music from the States was banned for being “provocative”–think Black Sabbath, Elvis Presley, and Louis Armstrong–Italian artists provided another access point to pop culture, albeit a more conservative version. My grandmother was familiar with the likes of Mina, Robertino Loreti, Adriano Celentano, and Toto Cutugno, who became widely popular, even surpassing their fame in western Europe.

Not all their songs, however, passed the scrutiny of Soviet authorities, and only select pieces were aired–but it was enough to have the Russian population going wild. Italian hits like Matia Bazar’s “Vacanze Romane” and Toto Cutugno’s “L’italiano” became massive successes on Soviet television and radio, and, by the late ‘80s, Italian bands were extensively touring the Soviet Union, with Ricchi e Poveri holding 44 concerts and reaching 780,000 fans at their peak. Even the Sanremo Music Festival took hold among Soviet audiences. Introduced in the late ‘70s through the TV show Melodies and Rhythms of Foreign Pop Music, the singing competition was heavily censored; the USSR maintained a tight grip on all foreign musical content.

Tarkovsky with the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival (1962)

CINEMA

Visual arts, on the other hand, had a much easier time crossing borders. Many Italian filmmakers traveled to the Soviet Union to share ideas and techniques, and Soviet filmmakers with the Italians in turn. Film festivals were a key breeding ground for this cultural exchange, with Soviet films increasingly taking to the stage to accept awards at the Venice International Film Festival and Italian films winning those in the USSR (most notably, Federico Fellini’s 8 1/2 took top prize at the Moscow International Film Festival in 1963).

The genre that swept the silver screen during this period was Italian Neorealism, which aimed to capture the harsh realities of life in a war-torn and economically devastated country. One of the most influential movements in cinematic history for its stark and raw portrayal of everyday life, Italian Neorealism tackled themes that those of the Soviet country could equally relate to.

Clear traces of Neorealist influence can be found in the most significant Soviet films of the mid-century. Mikhail Kalatozov’s The Cranes Are Flying (1957), inspired by Roberto Rossellini’s masterpiece Rome, Open City (1945), shifted attention away from military heroism and focused instead on the emotional and psychological experiences of everyday people. Its poignant, humanistic portrayal of love, loss, and the aftermath of war created a powerful emotional narrative that challenged conventional Soviet war films of the time.

Still from "Ivan's Childhood"

Andrei Tarkovsky’s early films–with real-world settings used to portray emotionally charged stories about war and suffering–similarly reflect a clear Neorealist influence. His 1962 film Ivan’s Childhood, considered by many to be the most emblematic film of the era, won the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival that year. Following the harrowing journey of a young boy, orphaned by the Germans, who becomes a scout for the Soviet Army during WWII, Ivan’s Childhood was just one of his many films that integrated the humanistic elements of Italian Neorealism. Mirror (1975)–is a visually poetic exploration of memory, identity, and the passage of time–is one example, but perhaps the best is Nostalgia (1983), co-written with Emilia-Romagnan Tonino Guerra (who also worked with Fellini). The film focuses on a Russian poet who travels to Italy to research an 18th-century composer; along the way, he grapples with profound feelings of homesickness and existential longing, his journey becoming a meditation on the nature of the film’s eponymous feeling and the search for a lost homeland.

Tarkovsky’s own fate didn’t fall far from that of his protagonist. In 1985, the city of Florence offered asylum to the exiled Russian director, who found his final home at Palazzo Vegni at Via San Niccolò 91.