A small, provincial town below the Piedmontese Alps of just 22,600 people, complete with a medieval orange festival, doesn’t really seem like it would be a beacon of tech innovation. But Ivrea, home of the famed Olivetti factory, is exactly that. Beside the cute piazze and ancient bridge, the long via Jervis hosts a strange linear building made of glass, iron, and concrete, reminiscent of rationalism and austerity, and, for those who know, a glorious past. So, on a cool October day, I hopped in my trusted 90 Punto to check it out for myself.

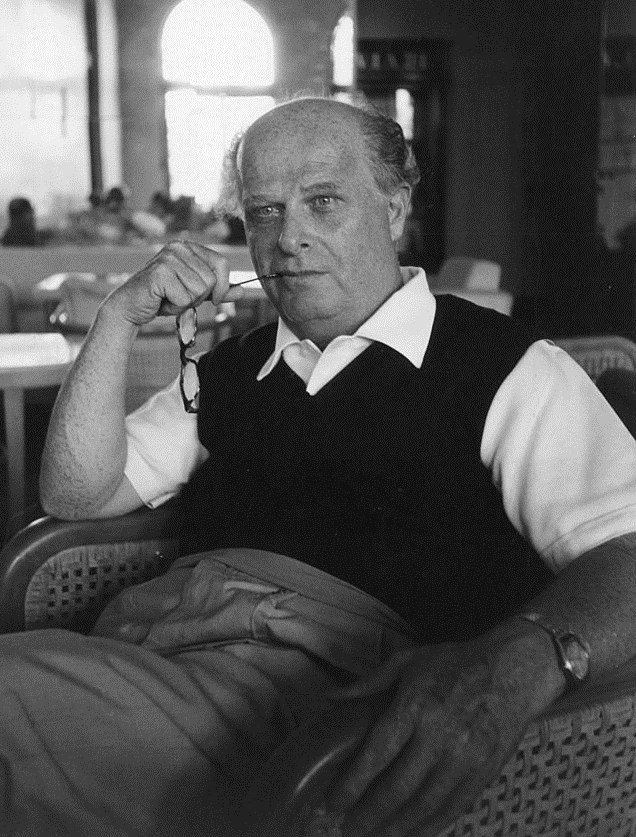

Adriano Olivetti sitting at a table in a bar in Venice, 1957

The extraordinary tale of the Olivetti family is one of grand ideas and visionary people; of Bauhaus, the Cold War, American secret services, and the very first personal computer. But first, a little bit of housekeeping. The Ing C. Olivetti & Co. was founded by Camillo Olivetti, an Italian Jewish electric engineer, here in 1896. The company specialized in instruments for electrical measurement until 1908, when they made the first Italian typewriter: the Olivetti M1. Conceived during the two years Camillo Olivetti taught electrical engineering at Stanford University in California, the machine was groundbreaking for its excellent features and elegant design. After a few more models, the M20, born in 1920, launched the company internationally, and they soon opened up supply chains in Spain, Brazil, and more.

Camillo’s second-born son, Adriano, took the reins in 1933, and the following 27 years are where things really got interesting. In a Tony Stark-esque way, Adriano was at the same time a genius entrepreneur, inveterate anti-Fascist, brilliant utopian, and socialist publisher. But the ways in which he ran the company not only morphed a family business into a world-famous brand–whose calculators also paved the way for electronic computing–but completely shaped manufacturing in Italy by embracing efficient urbanism without worker exploitation.

It should come as no surprise that Adriano actually did learn from Henry Ford while spending time in the United States in 1925. When Adriano took over the company, he matched the production system to what he saw in the U.S., transforming the shop into a factory with departments and divisions, implementing work turns, increasing the employees’ hourly salary, and organizing the assembly chain. The results were so positive–the workers actually doubled their output in just five years, not to mention were happier overall–that the company became the most successful business in Italy.

And if there was one thing Adriano knew how to do, it was make things stylish. He formed a group of designers (Marcello Nizzoli and calligrapher Giovanni Mardersteig, among others) and artists (Luigi Munari, Ettore Sottsass, Luigi Veronesi, Gianni Pintori) to create avant-garde machines that were not only functional, but visually stunning. Adriano Olivetti’s aesthetic intuitions were so special that New York City’s Museum of Modern Art dedicated an exhibition just to his typewriters in 1952.

Ettore Sottsass Olivetti typewriter featured at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London

Conceptually, Adriano despised capitalism, and Adriano shaped the Olivetti factories into spaces that matched his eye for aesthetics and ideas of production as a foil to the FIAT factory and the Fascist architecture that flourished under Mussolini. Away from the dirty, dusty Taylorist, brick-and-pipe factories, Olivetti buildings were bright, clean, and represented small societies. He was inspired most by the Bauhaus movement and Italian rationalist architects Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini, steering away from the northern European-inspired tower blocks and creating factories of glass: his employees had views of the surrounding Alps, and people outside were able to catch a glimpse of how the factory worked.

By the late 1950s, more than 14,000 people had flocked from all over the country to work in the tiny town of Ivrea. A job at Olivetti wasn’t just money, it was lifestyle. Available to employees were libraries; classes in history, civics, politics, and art; and film and art festivals. Renowned poets and writers like Pier Paolo Pasolini and Paolo Volponi came to give speeches. For Adriano, the key to creating a better world was education. Employees even could opt to live in Olivetti housing, which featured big windows, green space, and a vegetable garden.

Olivetti was the first company in Italy to introduce the five-day working week (cutting a day from the standard six-day week) plus the nine-month maternity leave; on average, an Olivetti employee earned a third more than a FIAT worker at the time. According to Adriano, putting the employees in the position that they were most equipped for and most preferred to do would increase their productivity, and a better quality of life would generate better results at work (yes, these were actually groundbreaking concepts at the time). And he was really onto something, because by the early 1960s, Olivetti was one of the leading typewriting companies in the world and the sixth most influential Italian company, with products sold in 117 countries and 54,000 employees across the globe.

Photo by Paolo Monti

Adriano was ahead of the game in technology, too, investing in informatics with the belief that they represented the future of communication. And in 1959, as if he hadn’t already achieved enough, he invented the Olivetti Elea, the world’s most powerful computer at the time, together with engineer Mario Tchou, a pioneer of computer science in Italy. Their Elea–which stands for Elaboratore Elettronico Aritmetico in reference to the Eleatic school of philosophy–was the first solid-state computer to be designed and manufactured in Italy; their main competitor the American IBM. But while the U.S. was investing in information technology, the Italian government, unsurprisingly, was not. As a result, the company decided to extend business to Russia and China–which proved to be a poor choice during the Cold War–eventually selling their mainframe business to General Electric in 1964.

In 1960, at only 58, Adriano suffered a deadly stroke while on a train to Switzerland. An autopsy did not follow, which (of course) fueled conspiracy theories about his death, some of which claim the U.S. Secret Service was involved. After Adriano’s passing, his first born Roberto Olivetti took the helm of the company, and it seems creativity, vision, and brilliance could be genetic. Together with engineer Pier Giorgio Perotto, Roberto led a design team that built the famous Programma 101 (also known as La Perottina): the world’s first programmable calculator, launched at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. About 10 of these “supercalculators”, so called by NASA employee David W. Whittle, were sold to NASA, and they were used to help plan the Apollo 11 moonlanding in the late 60s.

The idealistic visions of this family helped create the basis for space travel. Space travel! All because Camillo, Adriano, and Roberto Olivetti believed in education and respect, and that factories should be spaces of nurturing and training, rather than exploitation. (Imagine what some of the big corps could get done today, but I digress.) And it’s not all brand marketing. I spoke with Norberto Patrignani, a former employee of Olivetti’s Research & Development department. Thanks to the company policy regarding studies and education, Norberto earned a Ph.D in Computer Ethics at the University of Uppsala, Sweden, and eventually became a teacher at the Politecnico di Torino. He’s not the only one with a testimony like this.

Imagine, Italy nearly had its own Silicon Valley; Olivetti, our Bill Gates.