Lou Di Palo has been behind the counter at his family’s gastronomia for 72 years, but he jokes that he’s been there for 73–if you include the time his pregnant mother worked there too.

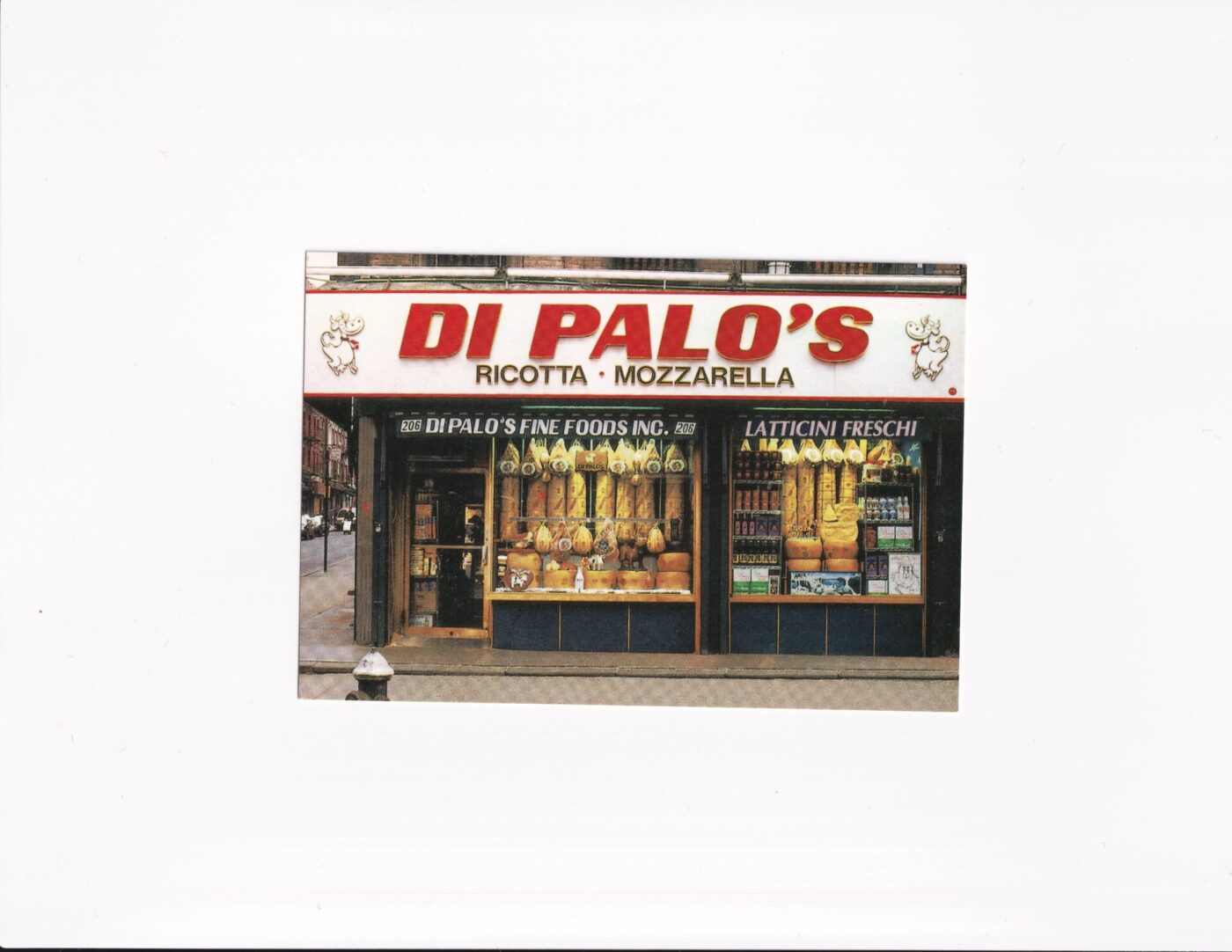

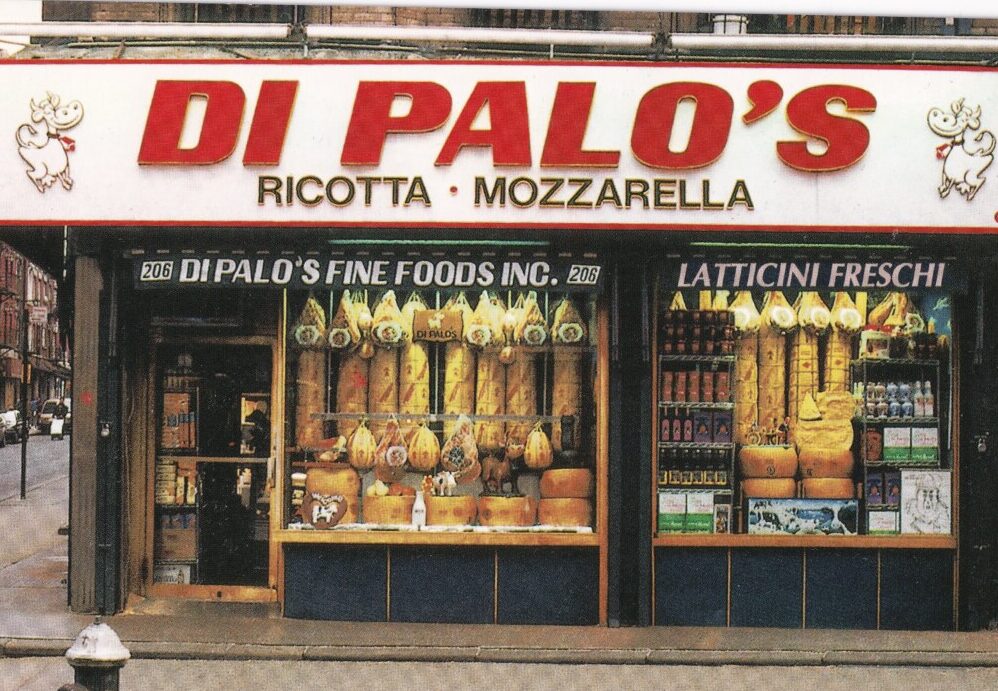

At the corner of Grand and Mott Street in New York City’s Little Italy, with dark green awnings and wheels of Parmigiano lining the windows, Di Palo’s Fine Foods has a small sign on the front door politely informing its patrons that there are no panini here. Your ingredients–superior olive oil, fresh mozzarella, the finest prosciutto di Parma–are to be taken to go.

Open since 1925, the latteria turned gastronomia is one of few places left in Manhattan’s Little Italy to find authentic Italian food and products–the bulk of establishments on the blocks surrounding Mulberry Street now profiting off a falsified image of the bel paese. The neighborhood was home to the first wave of Italian immigration, and while some came for two months, two years, or briefly, as a stop along the way–if you were Savino Di Palo, you stayed for a lifetime.

Before the mid-19th century, Italian presence in the city was minimal, with the 1850 census counting just 850 Italians–a number that would reach 4 million by 1920. Around the turn of the century, poverty-stricken conditions in the south of Italy provoked a diasporic mass immigration to the United States, and, at its height, the enclave of Little Italy housed 400,000 Italians. The neighborhood reached “almost all the way down to the financial district, up to 14th Street and from the East Village to the West Village,” says Marie Palladino, Head of Education at the Italian American Museum in New York. “Little Italy is the footprint of the Italian-American immigrant. About 85 to 90% of Italians that came over, came to the US. They stopped in that neighborhood before they moved on to other neighborhoods.”

During this time, the area bustled with Italians establishing a community with the skills, artistry, and cleverness they brought from home. They opened stores dedicated to Italian music, literature, and traditional delicacies, and fruit and vegetable cart vendors lined the roads as they did back home. And, like home, communities were defined by distinct subcultures and the regional origins of its residents–here, played out on the city streets. Simply put, if you weren’t Sicilian, then you didn’t live on Elizabeth Street. Mulberry was allocated for those from Campania and Mott for the Calabrese, eventually expanding to include those from Puglia and Basilicata.

The development of the area, in part, came from chain migration–the process through which one person is followed by family members or others from their community, like how the Di Palo’s arrived. Savino Di Palo was the first to land, moving from his small town called Montemilone, a mountainous region in Basilicata. Like many others, he immigrated to the United States with the hopes of providing a better life for his family. Savino was a blacksmith and dairy farmer by trade, and, upon his arrival, did what he was familiar with: made cheese, notably fresh ones like ricotta and mozzarella. In 1910, Savino opened his first shop, and, by 1914, he had saved enough money to bring over his wife and five children. As the family grew, Savino encouraged his children to start their own businesses, and so they did, all over the city–sadly, now all defunct. Back then, Little Italy alone had 30 latterias, while today only one remains–Di Palo’s.

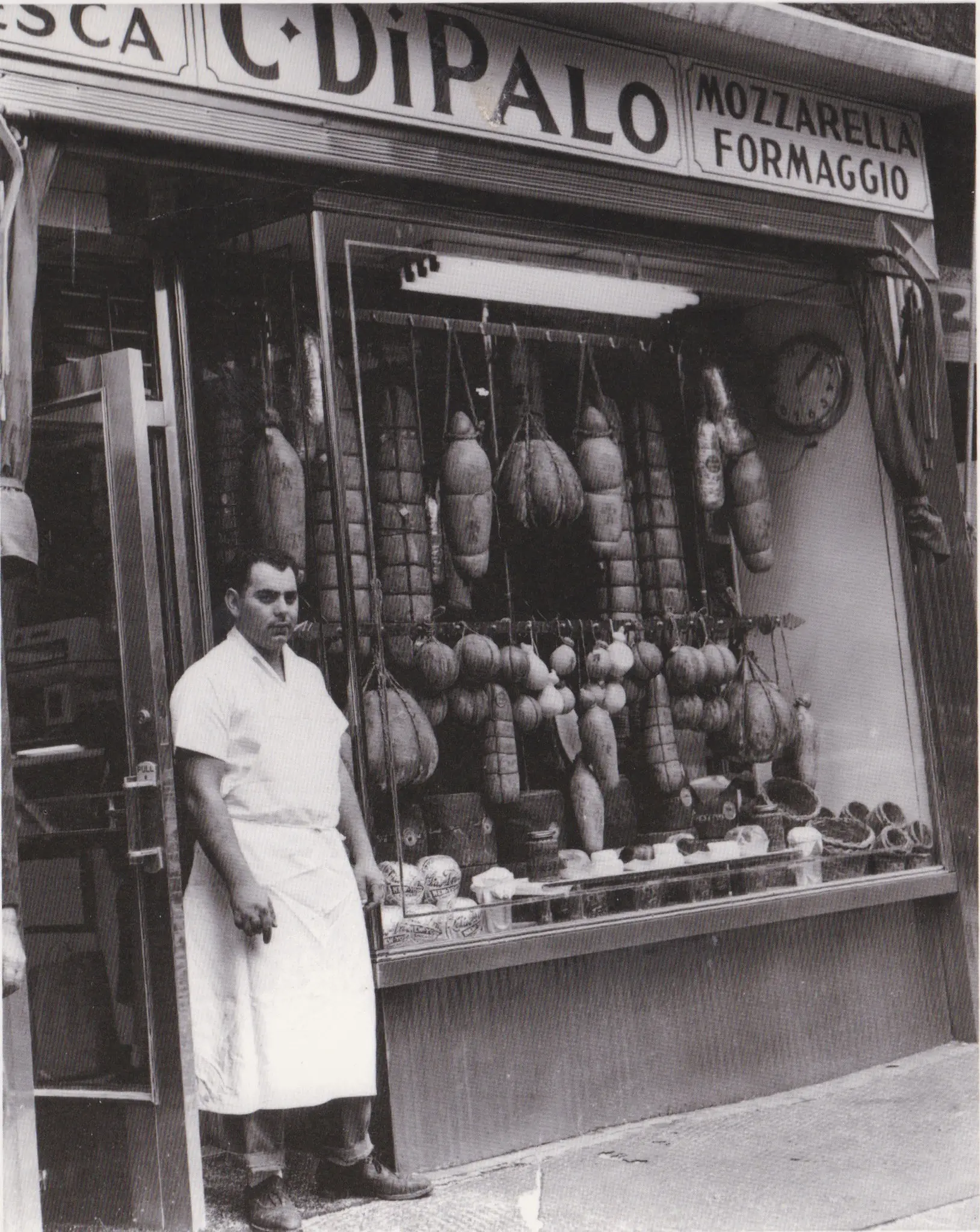

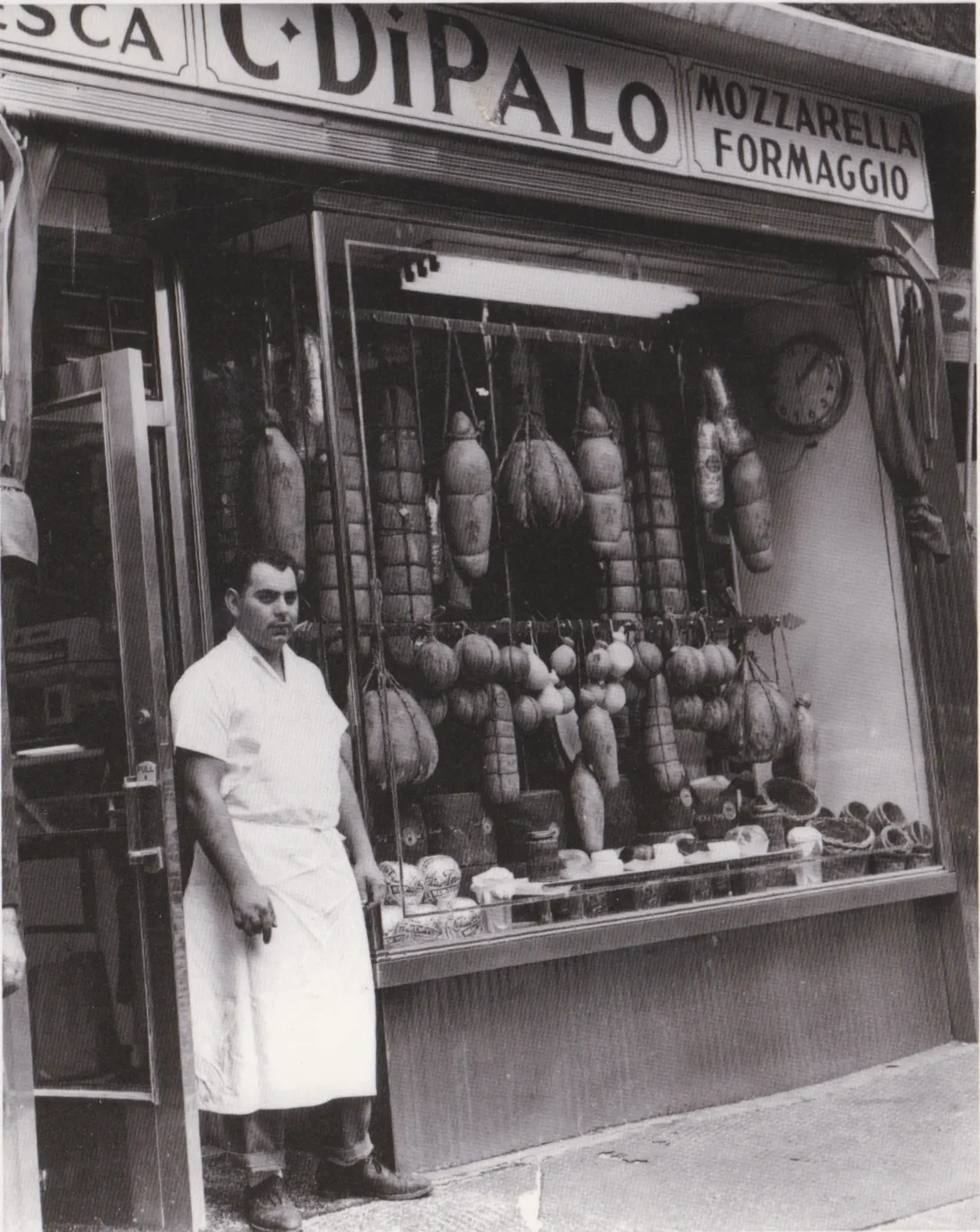

Courtesy of Di Palo's

The family members have vowed themselves to a lifetime of education on their Italian heritage. Lou is one of Savino’s great-grandchildren; he and his siblings Sal and Marie continue to run the family business alongside their children Sam, Jessica, Caitlin, and Michael. Several of them have taken their studies back to Italy, and the latest generation has now opened a wine bar around the corner called C. Di Palo–“Named after my grandmother Concetta,” Lou tells me. Traces of the Di Palo lineage are found in the shop, in photographs and postcards of generations passed, along with the family’s book “Di Palo’s Guide to the Essential Foods of Italy” which contains a foreword by Martin Scorsese.

Five generations later, the gastronomia has stayed true to its roots and continues to make fresh ricotta and mozzarella daily, keeping the Italian spirit alive in an area that is only becoming more and more disconnected from its heritage. It may be across from a bubble tea shop and next to a Vietnamese restaurant, but as soon as you step into Di Palo’s, it feels like Italy all the way. The smell of countless legs of prosciutto di Parma hanging from the ceiling wafts down, as the affettatrice whirs, carving slices of finocchiona, mortadella, capocollo, and any type of salame under the sun. You could spend months eating through their cheese selection alone, with the likes of grana padano, scamorza, ricotta salata, and gorgonzola dolce all on offer. Then there are the rows and rows of quintessential panty staples–olive oil and balsamic vinegar, dried pasta, cookies, and coffee beans–all imported from Italy.

Lou sounds like a New Yorker, but he pronounces things like an Italian. Tall and dressed in a Di Palo’s baseball cap with a black t-shirt, he exudes a no-nonsense demeanor. But despite his serious appearance, Lou is quick to share a warm smile. “We got the chips for you; I think Marie hid a box somewhere,” he shouts to the customer behind me in line. Here, patrons are remembered by name and for what they like to order, making relationships feel less transactional (in a city that’s often about transaction) and mimicking the norms of life in Italy. The incessant chatter and constant line are easy reminders of the shop’s far reach in the community.

While some refer to Little Italy as a tourist trap–popular, gentrified, overpriced–places like Di Palo’s hold the memories of a cultural landmark that, despite its evolution, warrants historical preservation. “The history will always be there; it’s our job as historians and activists of Italian culture to keep it alive and to remind people of its significance in the fabric of New York City, State, and U.S. history,” Palladino tells me.

When I ask Lou how his family has been able to maintain such a successful business after all these years–through world wars, the Great Depression, the pandemic, and an ever-changing neighborhood–he responds, “We never focused on what was outside. We always focused in. I didn’t worry about how the community was changing. I knew who we were, I knew our mission–to present to the consumer the best knowledge and products that Italy has to offer.”

The neighborhood will never again be an intimate enclave of Italian dialects, familiar faces, and traditions. Yet, Di Palo’s, and the family of the same name, give Little Italy a sense of permanence, ever so rare in the city that never sleeps.