His Excellency Police Commissioner Alfonso Molina was early that morning.

Anyone who had observed him up close, stripped of the deference he was accustomed to, might have detected a trace of impatience in the cadence of his otherwise calm and decisive stride. His thin lips, rarely known to yield a smile, were at times disturbed by a brief nervous twitch, promptly corrected by a stiff jerk of the neck.

He entered his office on the second floor of Piazza S. Nicolella with even greater haste. Hanging his hat and coat beneath the impassive gaze of the portraits of the King and the Duce, he summoned an officer and got straight to work.

Moments later, a slender young man with raven-black hair knocked at the door.

— “Officer Torrisi, Your Excellency!”

— “Torrisi, be seated. We have urgent work ahead, and I am told you are the swiftest with the typewriter.”

20 January 1939 – Year XVII of the Fascist Era [*]

To His Excellency the Prefect

President of the Provincial Commission

for Confinement

Catania

The scourge of pederasty in this city appears to be worsening and spreading, as youths hitherto unsuspected now show themselves afflicted by this form of sexual degeneration, both active and passive, which not infrequently leads to venereal disease.

It is with no small sorrow that nowadays we must observe the proliferation of such sick individuals in cafés, dance halls, seaside and mountain resorts, depending on the season, where they are received in great number. Young men from all social classes now openly seek their company, preferring their enervating and degrading affections.

The Police Commissioner paused.

— “Do you understand, Torrisi, the gravity of the situation? This city is overrun: from the sidewalks of Via Etnea to Piazza Roma, from the Duomo district to the Ursino Castle, to the gardens of Villa Bellini. Cinemas and otherwise respectable cafés are infested with these inverts… these pederasts.”

Torrisi merely nodded.

— “It has been nearly two years since the Reitano murder, Torrisi. October 15th, 1937. Do I have to remind you of the details of that crime? The ragioniere [clerk] was found dead on the floor of his apartment, his skull fractured. Of course, no one mourns a dead pederast. But after two years of inquiry, the case remains unsolved. And that’s because pederasts are deceitful, duplicitous, and insidious. Yet, we have studied them, shadowed them, and we know how and where they move. And if we have not yet closed down the dance hall in Piazza Sant’Antonio, it is only because it is a mine of information. We receive dozens of tips from upstanding citizens. We detain suspects and promise them immediate release should they provide names of other pederasts. And they talk, frightened, sniveling. Patientia vincit omnia, Torrisi. Patience. Patience is key. Let us proceed.”

This contagion of degeneracy has drawn the attention of the local Police Headquarters, which has intervened to suppress, or at the very least contain, such a grave sexual aberration, offensive to morality and injurious to the health and improvement of the race. Alas, the measures employed thus far have proven insufficient.

— “Look at these, Torrisi: the medical records do not lie.”

Molina waved in the air a sheaf of documents. Raising his voice, he read aloud, randomly picking at the documents:

— “Accustomed to unnatural coitus in habitual fashion. Fissures of centripetal type. Relaxed sphincters. Suffering from syphilis contracted through anal intercourse.”

The detentions, the medical examinations, the heightened surveillance over public venues and thoroughfares: these no longer suffice.

Molina fell silent, lifted his chin and closed his eyes as if to gather his thoughts. He approached the window to survey the city. Though it was January, the sun bore proudly upon the rooftops. The commissioner’s gaze fixed first on the dome of the Collegiata across the street, lingered on Santa Maria dell’Ogninella, and then on the roof of Teatro Bellini, before losing itself in the deep blue of the Ionian Sea glimpsed between the city’s buildings.

— “Have you ever been outside of Sicily, Torrisi?”

— “No, Excellency…”

— “Well, that’s understandable. You are still very young. One day, you shall visit the glories of our Fatherland. There are many, after all. The Divine Providence bestowed upon our peninsula a terrain both rich and varied: its peaks, its lakes, its plains all speak the language of harmony and order, as does the soul of its people.”

Molina’s upper lip twitched, as if stirred by a small electric current, before he resumed.

— “…and its islands. Indeed, Torrisi, the islands: Lipari, Ventotene, Ponza, Ustica, the Tremiti Islands… Remote islands, cast upon the Mediterranean, ideal for isolating from our cities those insidious criminals, so they may no longer corrupt others with their arguments and their lust. Thus we fulfill the project of the Fascist man: stronger, more sober, more combative, more virile. Now, where were we?”

— “‘… Detentions no longer suffice.’”

— “Ah, yes. Let us proceed.”

I therefore deem it indispensable, in the interest of public decency and the health of the race, to intervene with more vigorous measures, that the contagion may be struck at its root and cauterized. Let the remedy of Police Confinement be applied against the most obstinate, among whom I hereby submit the following names…

— “And here, Torrisi, insert the names on this list, one by one, with their corresponding case files.”

Molina handed the young man a page, adding:

— “All 53.”

* * *

The 45 exiles confined to San Domino were surrounded by the sea wall: only to the east could the island of San Nicola be seen. @Luana Rigolli

The words Molina dictated that morning marked the beginning of one of the darkest chapters in Catania’s history.

Under Fascist rule, homosexuality in Italy was both stigmatized and effectively erased, both socially and legally. Though absent from the official penal code, a discretionary law targeting “those who posed a threat to public morality or order” gave authorities broad powers to police and persecute LGBTQ+ individuals. Men suspected of same-sex relations were often imprisoned, institutionalized, or exiled to remote islands—sometimes for as long as five years.

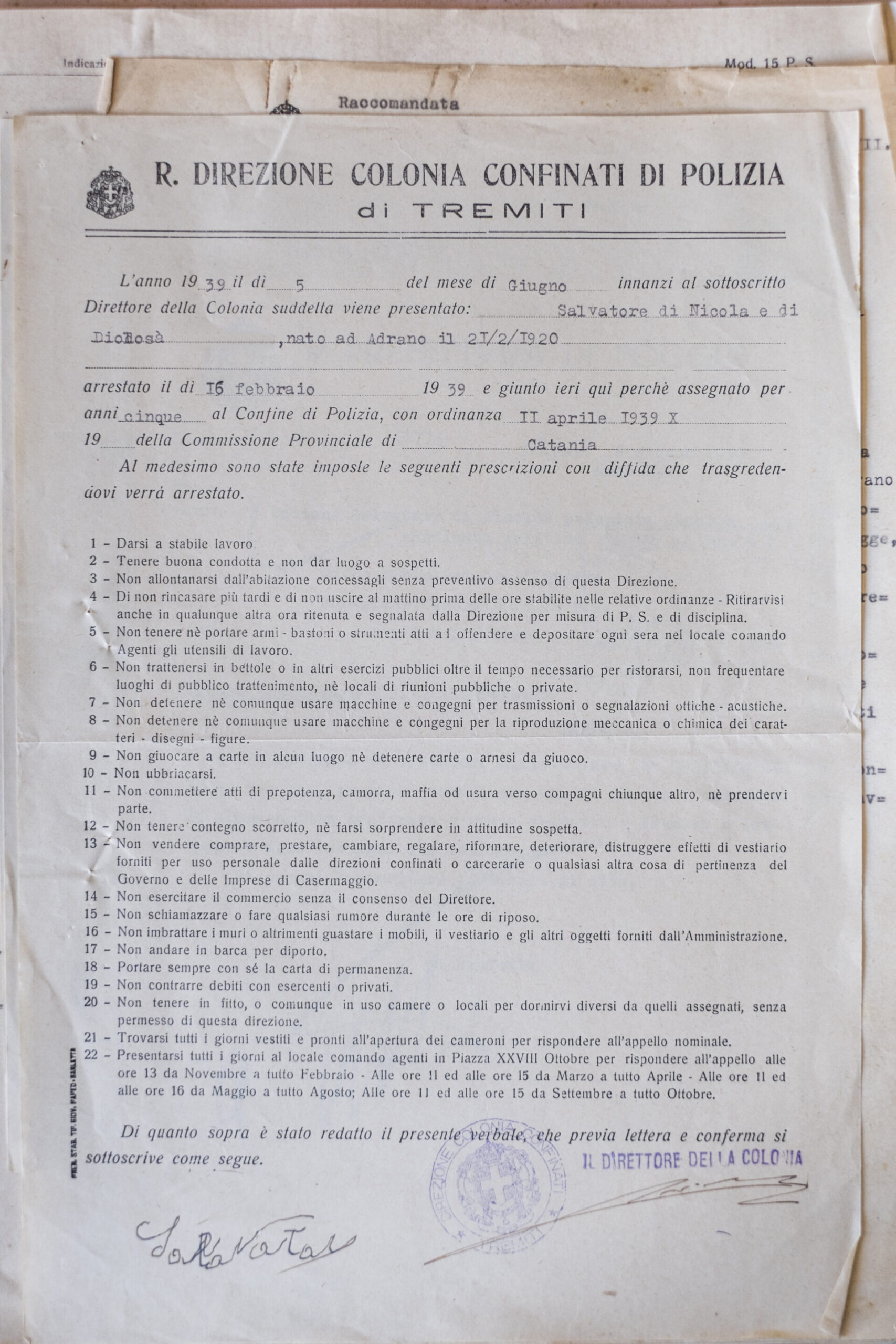

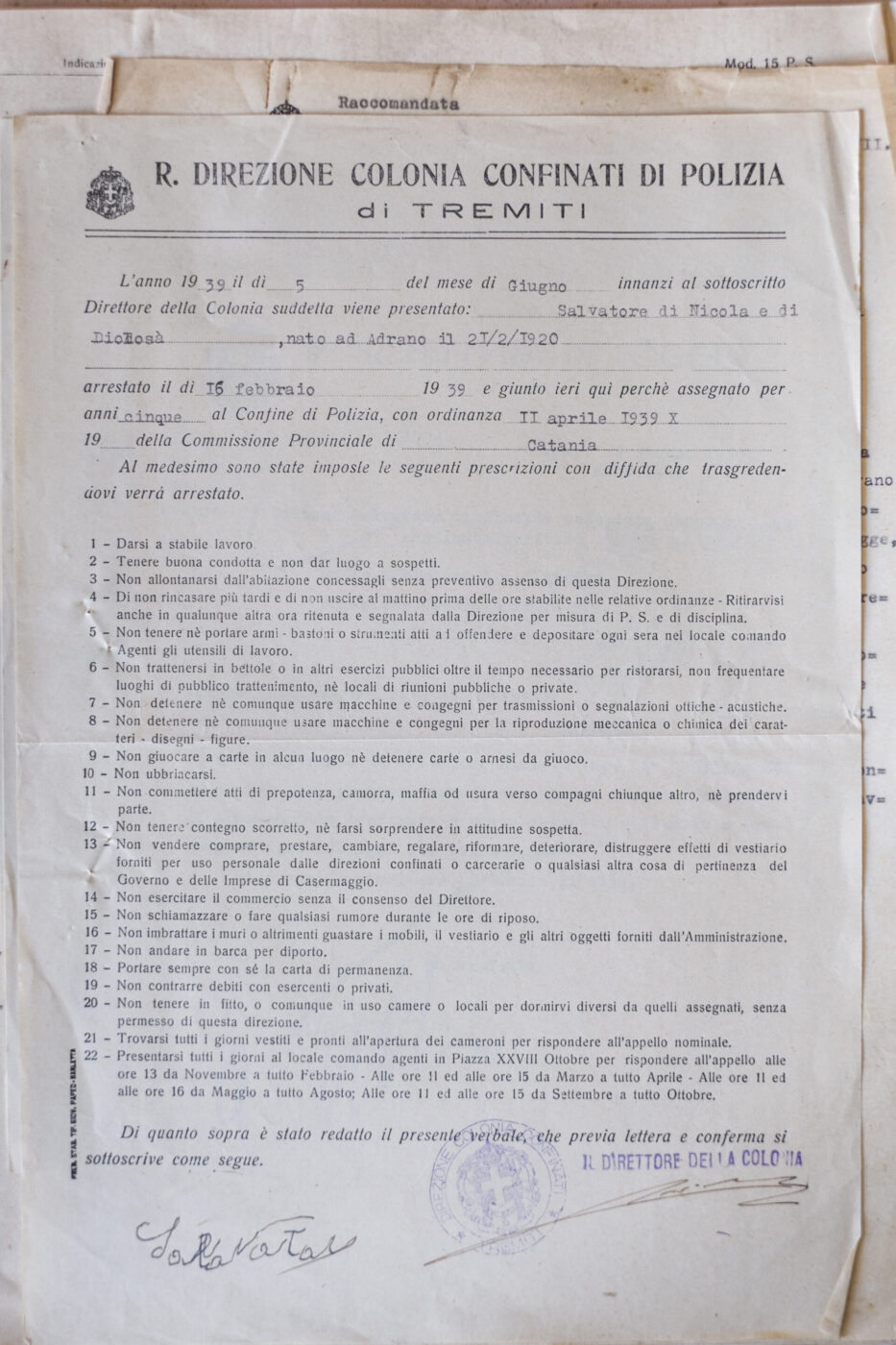

Between 1938 and 1941, several hundred men from across Italy—commonly referred to in official records as “pederasti”—were deported to the Tremiti Islands, a small, rocky archipelago in the northern Adriatic off the Gargano Peninsula of Puglia.

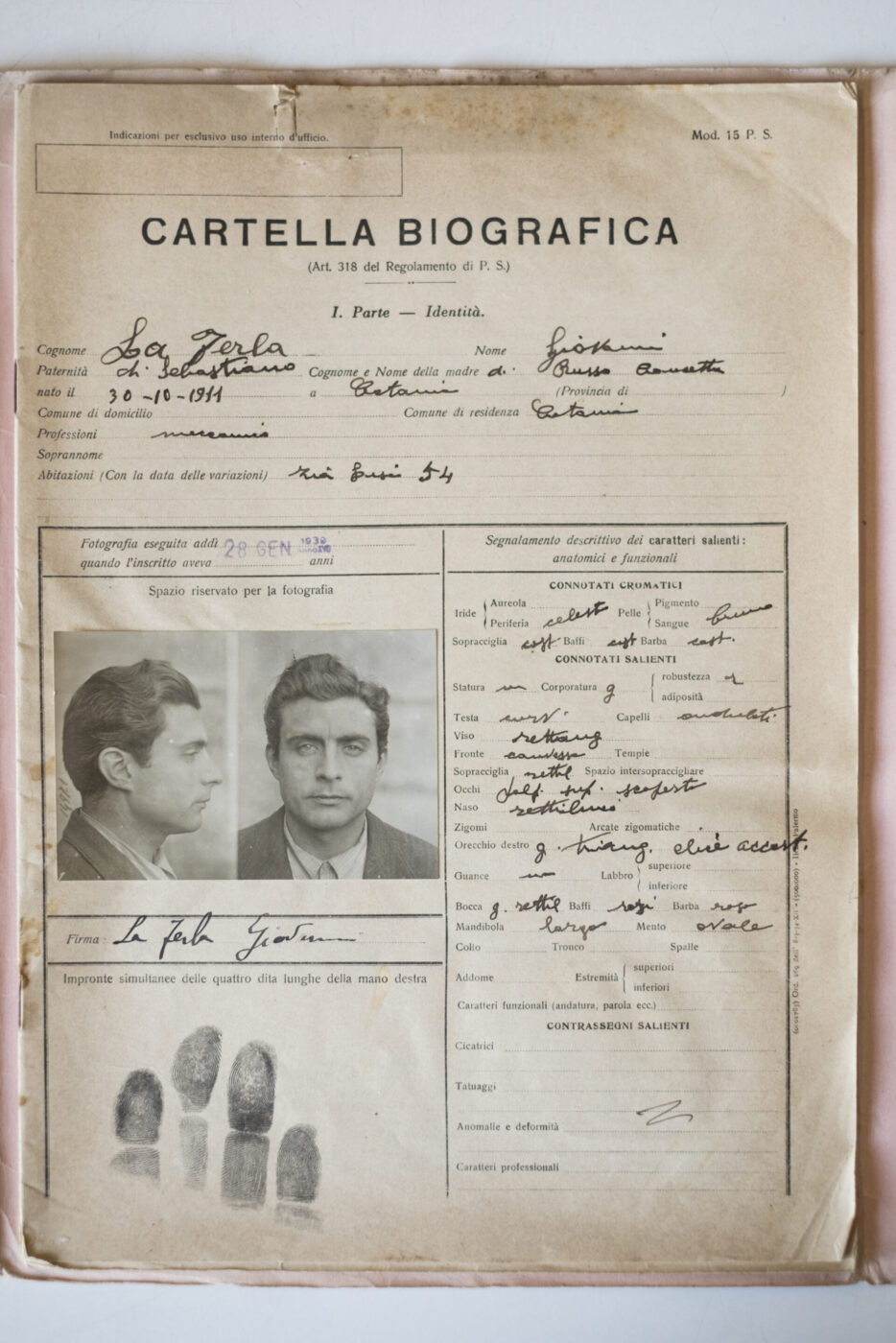

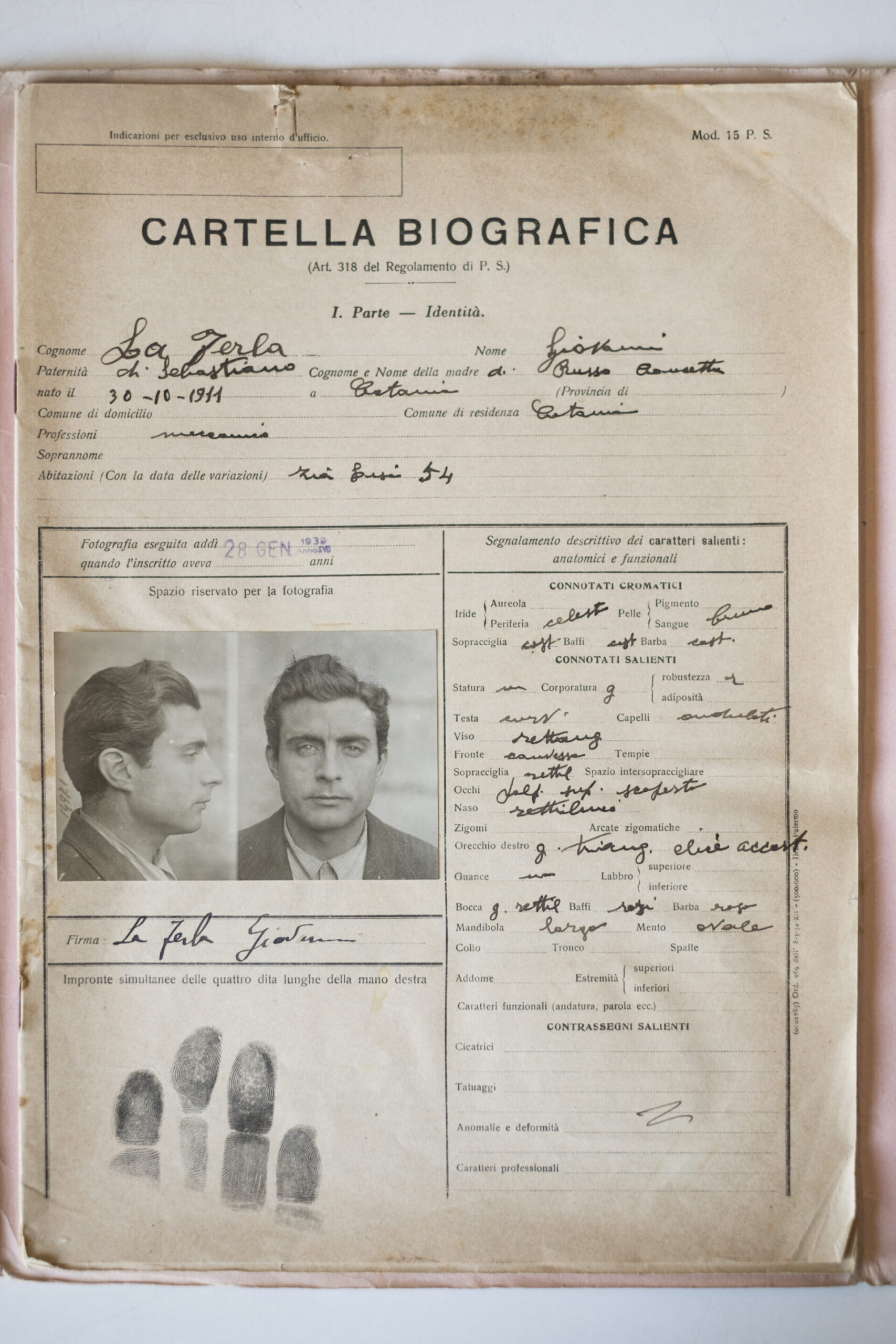

“They were arrested at home, at their workplaces, in parks, on the street, or in dance halls, usually at night,” write Gianfranco Goretti and Tommaso Giartosio in their book La città e l’isola, Omosessuali al confino nell’Italia fascista (The City and the Island: Homosexuals in Confinement in Fascist Italy). “Sometimes it was due to a denunciation, but more often it followed long and methodical investigations by public security forces. These were not dandies or decadent aristocrats, but mostly laborers, tailors, and farmhands. A few clerks or schoolteachers, and many who were illiterate.”

The arrests were often followed by degrading medical exams, including rectal inspections intended to provide pseudo-scientific “proof” of homosexuality.

San Domino, the largest of the Tremiti, was designated to hold these detainees. Uninhabited at the time, it lacked basic infrastructure: no sewage system, no running water, no employment opportunities, and a chronic shortage of food. Just under 3 kilometers long and nearly 2 wide, the island rose sharply from the sea, its steep cliffs making escape nearly impossible. The jagged coastline was carved with rocky coves, caves, and narrow inlets.

The aforementioned questore Alfonso Molina, Catania’s police commissioner, was responsible for one of the most repressive of these anti-homosexual campaigns. Already known for earlier crackdowns in Salerno, Molina seized on the unsolved murder of the gay clerk in 1937, as a pretext to expose the private lives of dozens of homosexual men—referred to, with contempt, as “arrusi” in the local dialect.

Of the 53 individuals he recommended for police confinement, 45 men between the ages of 18 and 54 were arrested on charges of “passive pederasty”—considered a crime against public decency and the integrity of the race—and were eventually deported to San Domino.

“Those poor devils—among them there were good craftsmen, even teachers—lived in terrible conditions,” Mario Magri, a political prisoner interned on the nearby island of San Nicola, later recalled. “They were paid four lire a day and packed into two filthy wooden barracks, surrounded by barbed wire that kept them confined to just a few square meters.”

The biographical files of the internees @Luana Rigolli (The Central State Archives is the owner of the original documents reproduced here. Further reproduction and duplication by any means is prohibited).

And yet, in spite of the isolation and hardship, something remarkable happened on San Domino: a sense of community emerged. Some men even fell in love.

“Everyone tried to keep busy: those who knew how to make shoes became cobblers, those who could sew did tailoring,” former detainee Giuseppe B., from Salerno, recalled in a rare 1987 interview conducted by historian Giovanni Dall’Orto. “I had the best job of all: I was the ‘seamstress’ for the carabinieri, and every morning they’d show up half-dressed… There was one, his name was V.—so handsome! I still remember him, even 40 years later. We tried to live as best we could. We laughed, we put on plays, we celebrated things… A telegram would arrive saying a new femmenella was on their way, and we’d each chip in a lira to prepare a feast.” (Note how Giuseppe uses femmenella, a dialectal term from Campania for gay men, rather than the Sicilian arruso.)

Unwittingly, and quite ironically, the Fascist regime had created one of the only places in Italy where being openly gay was, in a way, accepted. For the first time in their lives, these men found themselves free from the moral scrutiny that defined devoutly Catholic 1930s Italy.

“There were two cousins from Paternò, one a sculptor, the other a painter, who would organize everything, telling us to gather flowers, hang decorations, and so on,” Giuseppe continued. “Honestly… we lived better there than outside. Back then, if you were femmenella you couldn’t even leave your house: if you drew attention to yourself, the police would arrest you. But in confinement, we could celebrate someone’s onomastico [name day celebrated on the feast day of one’s patron saint], welcome a new arrival… It helped pass the time. We even did theater, and of course we could dress as women without anyone saying anything. Some femmenelle cried when we were transferred from Tremiti!”

On May 28th, 1940, by order of the Chief of Police and with Mussolini’s approval, the 56 remaining men were released. Their sentences were converted into two years of ammonizione—a repressive police measure that imposed curfews, travel bans, and mandatory check-ins on those deemed “socially dangerous,” without the need for a criminal conviction. Their release, rather than an act of mercy, was a matter of logistics: the regime needed space to detain Italian antifascists returning from the Spanish Civil War, now seen as the greater threat. Two weeks later, Italy entered World War II on the side of Nazi Germany.

The fate of the men sent to San Domino remains largely unknown. So much of their story was buried, and aside from the police files that led to their arrest, very little documentation exists. Few testimonies were ever recorded, and it’s believed that none of the men are still alive today. What we do know is that some ended up in prison again. Some married to maintain appearances. A few, upon returning to Catania, left the city altogether. After the war, still hardly a hospitable time for queerness, many chose to forget—or to remain silent—even decades after their imprisonment.

Questore Alfonso Molina was removed from his post on August 5th, 1943. At the end of the war, fearing he might be sent to an Allied internment camp, the same man who had spent years hunting down those deemed “unmanly” reportedly broke down in tears.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

*The text dictated by Questore Molina in the short narrative is an excerpt from the real report sent to the Provincial Commission for Internal Exile, attached to the case files of all the convicted men from Catania.