Long before Armani, Prada, and Gucci became go-to labels for red-carpet dressing, there was the Casa di Moda Sorelle Fontana, helmed by three intrepid sisters from rural Italy who dressed the world’s biggest celebrity names during Italy’s dolce vita heyday and created a global business in an era when few women even worked.

In 1943, while WWII continued to rage, siblings Zoe, Micol, and Giovanna Fontana decided, despite the apparent perils, to launch a fashion atelier in Rome, a decision that eventually would help position the Eternal City as a couture capital to rival Paris.

1960. The three Fontana sisters (from left: Zoe, Micol, Giovanna) Photo: Arturo Ghergo Courtesy: Micol Fontana Foundation Archive, Rome

Although the investment was a modest 500 lire, the risks, at least on the surface, seemed enormous. Rome continued to suffer from frequent bombardment, there were severe food, supply, and job shortages, and residents were still more focused on survival than anything else.

But making clothes was the Fontanas only livelihood, and despite the relenting grimness, there were stirrings of hope. The Allies were progressing up the coast from Sicily, and Rome was finally liberated in June of 1944. Italy’s postwar years were to usher in a new, unimagined prosperity, yet even in peacetime, there were no guarantees that the Fontana maison would thrive. While fashion was traditionally a more welcoming sector for female entrepreneurs than other fields, with labels led by designers like Elsa Schiaparelli and Biki (Elvira Leonardi Bouyeure) founded before the war, and Irene Galtizine, Simonetta, and Mila Schön heading up their own ateliers afterward, these couturiers often came from aristocratic families with good connections or enough resources to fund their efforts.

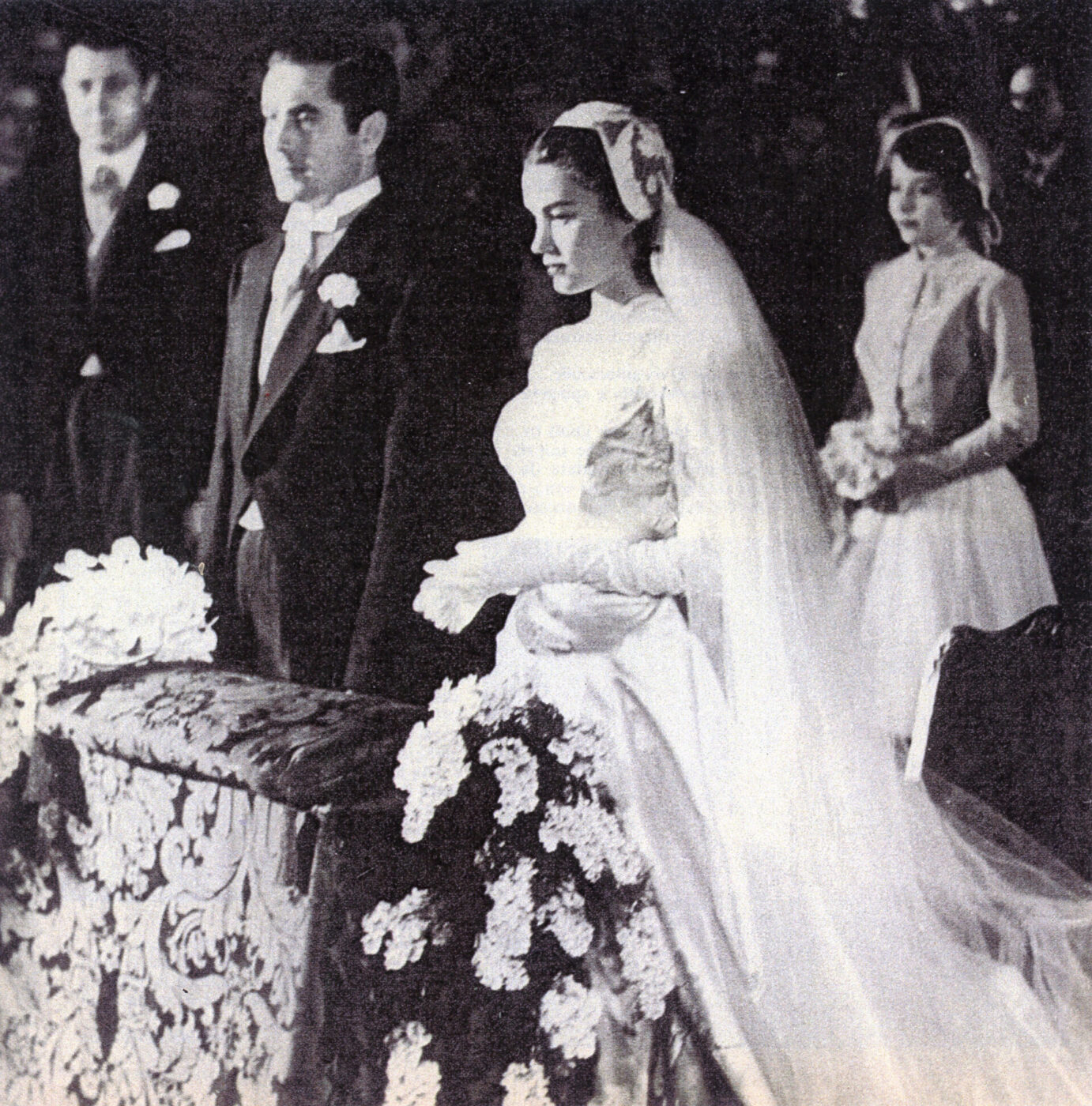

1949. Linda Christian trying on her wedding dress at the Sorelle Fontana atelier for her marriage to Tyrone Power. On the left: Giovanna Fontana, on the right: Micol Fontana Courtesy: Micol Fontana Foundation, Rome

From Small-Town Seamstresses to Roman Couturiers

With an unwavering, if somewhat unscripted, ambition to showcase their talents on a bigger stage than their hometown, Traversetolo, could provide, the sisters decided to cast their net beyond the provinces of Parma, although where that would be was originally up for grabs. According to family lore, Zoe, who had apprenticed at an atelier in Paris and was the first of the sisters to leave home, decided she would let chance (or rather the Ferrovie dello Stato) determine her destiny. When she arrived at the station she decided to head to whatever big city the next train was traveling to. It was bound for Rome. Not long after, Zoe’s sisters and parents, Amabile and Giovanni, followed.

“We were little dressmakers,” Micol Fontana told The New York Times in 1954, speaking modestly of their first years in the Eternal City. While they were initially anonymous, there was nothing modest or “little” about their capabilities—they came to Rome with a superb sartorial savoir-faire honed in the family dress shop headed by their mother, who instilled a daunting work ethic. Roberta Lami, Giovanna’s daughter, and now president of the Micol Fontana Fondazione, says she believes the label succeeded during those difficult times, not only because of the sisters’ hard-earned talents and deep-rooted professionalism, but also because they possessed a “strong spirit of sacrifice.” She notes, “They even bartered agricultural goods to obtain fabric—proof of their ingenuity and determination.” What also helped enormously, says Lami, was having parents who encouraged their daughters’ ambitions, which were highly atypical for the period, when women, even if they had wartime jobs, turned their focus back to the home after the fighting stopped.

1954. Elizabeth Taylor wearing an evening gown made for her by the Fontana sisters. Courtesy: Micol Fontana Foundation Archive, Rome

The Fontanas Take on the Silver Screen

Once established on their own, the Fontanas’ reputation grew quickly via an elite grapevine that reached from the affluent denizens of Parioli to members of the local aristocracy. It didn’t hurt that their made-to-order pieces were better priced than couture in Paris; what helped, too, was their address near Via Veneto, certainly easier to get to for fittings than the Rue Cambon or Avenue Montaigne.

But the Fontanas offered more than good value and convenient geography. Their early collections evolved the New Look introduced by Dior in 1947, adding a beguiling sensuality to the wasp-waist, full-skirt silhouettes in demand at the time. The Sorelle Fontana fit was often discreetly sexier than other couture labels; clothes were tailored with a fluid precision that yielded a graceful sinuousness to their designs. The Fontanas experimented with various curvaceous cuts like 8-shape and hour-glass forms, defined by snug bodices and a contoured hip, and produced them, especially when it came to evening wear, with sumptuous, label-defining pizzazz.

In the 1950s, they added fresh alternatives to still popular cinched-waist styles with modern sheaths for day and evening. With their skill at form-fitted tailoring, the Fontanas gave this classic a powerful new allure, well demonstrated in an image of Elizabeth Taylor at the atelier wearing a dramatic, one-shouldered silk pencil dress.

Perhaps as important as cut was the Fontanas’ prowess with embellishment, using centuries-old Italian embroidery, lacework, layering, and beading techniques and sourcing locally produced materials like Neapolitan coral, Murano glass, and gold filigree to rival the work of Paris’ much vaunted les petites mains, the revered French artisans skilled in rarified dressmaking arts. The Fontanas’ couture capabilities, along with constant research to find extraordinary fabrics (silks from Como, wools from Biella) led to what Roberta Lami describes as “a distinctive Italian style that stood as a credible alternative to the dominant French fashion of the era. They managed to transform tailoring into art.”

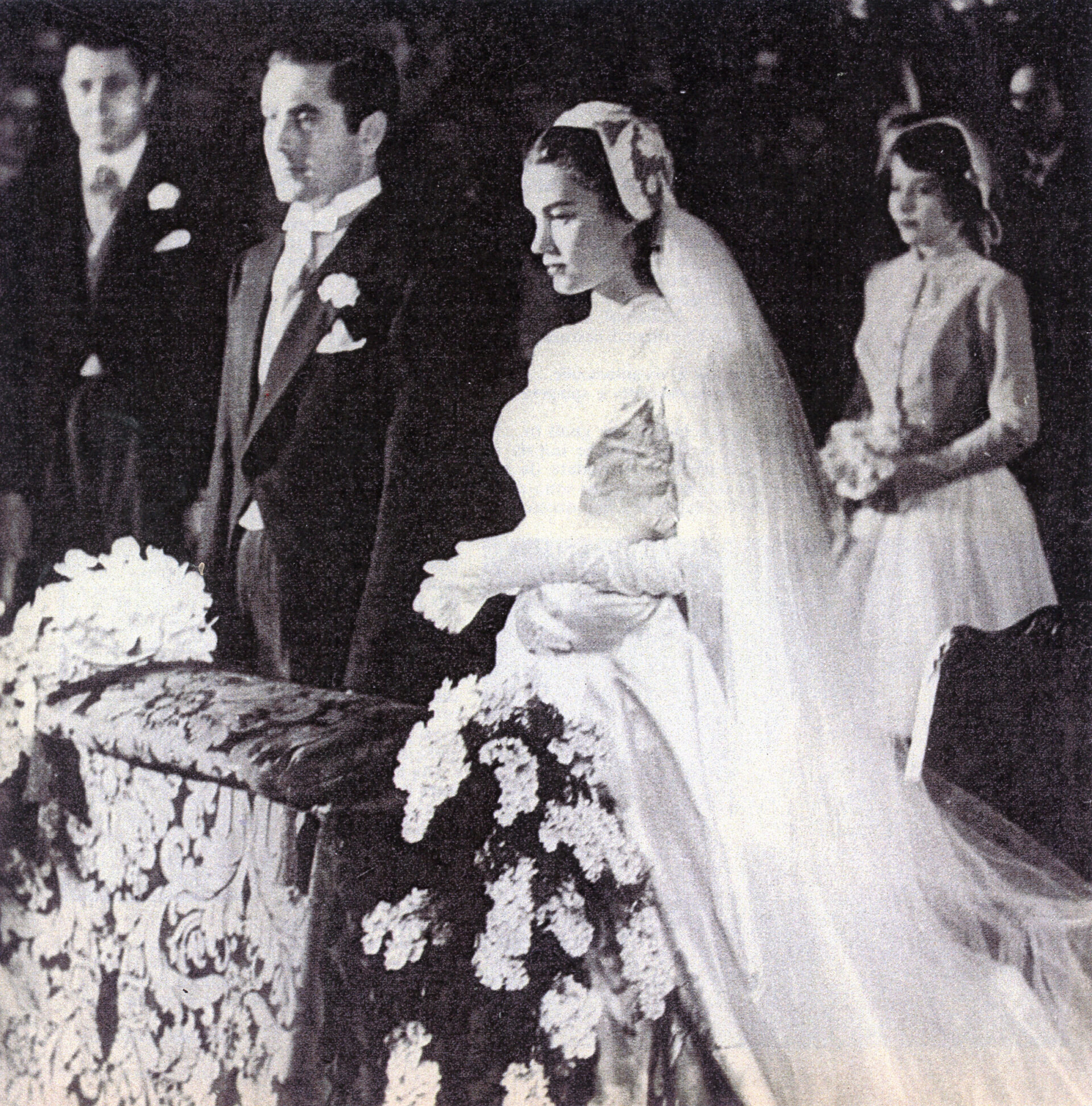

One impressed client suggested the Fontanas to an American actress named Linda Christian, who commissioned them to design the dress she would wear for her wedding to the mega-movie star Tyrone Power, which took place in Rome in 1949. The event generated such widespread coverage that it rivaled for its time the media frenzy surrounding Amal and George Clooney’s nuptials many decades later.

1949. Linda Christian with Tyrone Power on their wedding day. Courtesy: Micol Fontana Foundation, Rome

The details of the dress were reported on as extensively as wedding gowns worn by British royals, generating exceptional levels of publicity for the maison. Designed in heavy ivory satin, the column-shaped, contoured dress was covered with intricate embroidery; an overskirt flowed into a dramatic 25-foot train worthy of the grandest basilicas (the wedding took place at the Basilica of Santa Francesca Romana).

Their base in Rome would soon yield another bonus to further strengthen their ties to cinema’s biggest names, as the city transformed into an outpost of Hollywood during the 1950s and international filmmakers decamped to Cinecittà to make movies at cheaper costs than in Los Angeles.

The Fontanas weren’t only dressing stars who came to town (Elizabeth Taylor, Audrey Hepburn, Rita Hayworth) for filming; they soon were creating costumes for some of the best-known movies of the day, like The Barefoot Contessa (1954), The Sun Also Rises (1957), and On the Beach (1959), all films starring Ava Gardner, one of their best-known clients who became a family friend. (Gardner stipulated in her contracts that the Fontanas create her film wardrobes.)

Their work for Hollywood highlighted the label’s luxuriant glamour, which led to more renown, but also to a portfolio that reached beyond the needs of the typical couture clientele of socially prominent elites. For The Barefoot Contessa, for example, Gardner’s wardrobe ranged from the lavish gowns associated with the label to the type of casual clothes—shorts, cardigans, simple shirts—you would expect from American sportswear designers, although made with couture-like fit and worn by Gardner with a certain dolce vita flair.

While not a film costume, Gardner helped make one of the Fontanas’ most unusual designs famous when she was photographed wearing the dress, Il Pretino (or little priest). An example of how the Fontanas’ innovated by drawing on unexpected cultural and historical references, the red-and-black cassock-style garment with a clerical collar was the stand-out item in the maison’s Cardinal line (1956). (While it generated controversy, the Catholic church had given the Fontanas permission to create it.) Il Pretino would go on to inspire a costume worn by Anita Ekberg in Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960), although the dress’s use here was commentary of the sly cultural type rather than of fashion.

1955. Ava Gardner wearing the “pretino” dress from the “linea talare” Autumn/Winter 1955/56 Collection. The concept of the dress was later reprised by Federico Fellini for Anita Ekberg in La Dolce Vita (1959). Courtesy: Micol Fontana Foundation, Rome

Exporting Italian Elegance

Thanks to their fame, Sorelle Fontana was among the first Alta Moda houses to enjoy an international customer base as it looked beyond Italy and the United States to develop markets in Russia, Japan and other parts of Asia. While primarily known as a couture house, and a favorite of elite brides (including presidential daughter, Margaret Truman), the Fontanas added prêt-a-porter and accessories in the 1960s to accommodate a wider audience, and later launched a home collection, the type of brand extension that’s commonplace for many fashion houses today.

The Fontana label would endure as a symbol of Italy’s couture for 50 years, and later, as the women’s movement took root, as a remarkable example, avant la lettre, of a gutsy, female-led company that defied societal and business norms. The maison received many accolades during the half-century it was in business. There was a fictional miniseries about the Fontana sisters’ rise to fame on RAI, the Italian network, which drew 9 million viewers, a documentary, books, and numerous awards, including for Micol the Cavaliere di Gran Croce, Italy’s equivalent of a knighthood/damehood. Their clothes are in major museums throughout the world like the Metropolitan Museum and Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Civic Museums in Venice.

Original sketches from the 1950s and 1960s preserved in the Micol Fontana Foundation

Inside the Fontana Archive: A Vintage Treasure Trove Near the Spanish Steps

The sisters showed their Alta Moda collections in Rome until 1972, and 20 years later, sold the company to an Italian investment concern. After the sale, Micol Fontana established an eponymous foundation, located at Via di San Sebastianello, the Fontanas’ last address near the Spanish Steps. It is one of Rome’s unique, under-the-radar attractions, a fashion center that showcases Italian couture during its important, formative years.

More intimate than a typical fashion museum, the Fondazione’s rooms are packed with mannequins dressed in some of the Fontanas’ most memorable works, archival black-and-white photos and period furniture, making it feel as if you’ve walked into a rarified vintage boutique. The must-sees amid the trove of richly ornamented ball gowns and tailored day wear are Linda Christian’s blockbuster wedding dress, Il Pretino, and the nodi d’amore, or love-knot dress, a black-and-white-confection with a swirling knot motif, that became an iconic look of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Le Amiche (1955).

“My mother [Giovanna Fontana] always said, ‘You can make history, even with clothing,’” Roberta Lami, the non-profit’s president, points out. “For her, every dress had to tell a story, and that principle still guides our work at the foundation.” In addition to housing the maison’s famous garments, the archive includes extensive embroidery samples, accessories, fashion sketches, photographs, a library, and periodicals, says Lami, which are frequently sourced by the many fashion students who come from Italian and international schools to visit and study the heritage of Italian couture.

“Our greatest dream remains to find a larger venue—one that would allow us to welcome more visitors, host more courses, and permanently display a greater number of archive pieces,” says Lami. “Micol Fontana always envisioned a Museo della Moda in Rome that would serve as a point of reference for scholars and fashion lovers, telling not only the story of the Sorelle Fontana but of the early days of Made in Italy. Every group of visitors—especially from abroad, where fashion museums are more common—asks: ‘Why isn’t the foundation part of a larger museum?’ Perhaps one day, it will be.”

To visit: The Micol Fontana Fondazione is open for private small-group visits, which last about 90 minutes, and need to be reserved in advance via email: info@fondazionemicolfontana.