The 1980s—the Boy Toy years of Madonna.

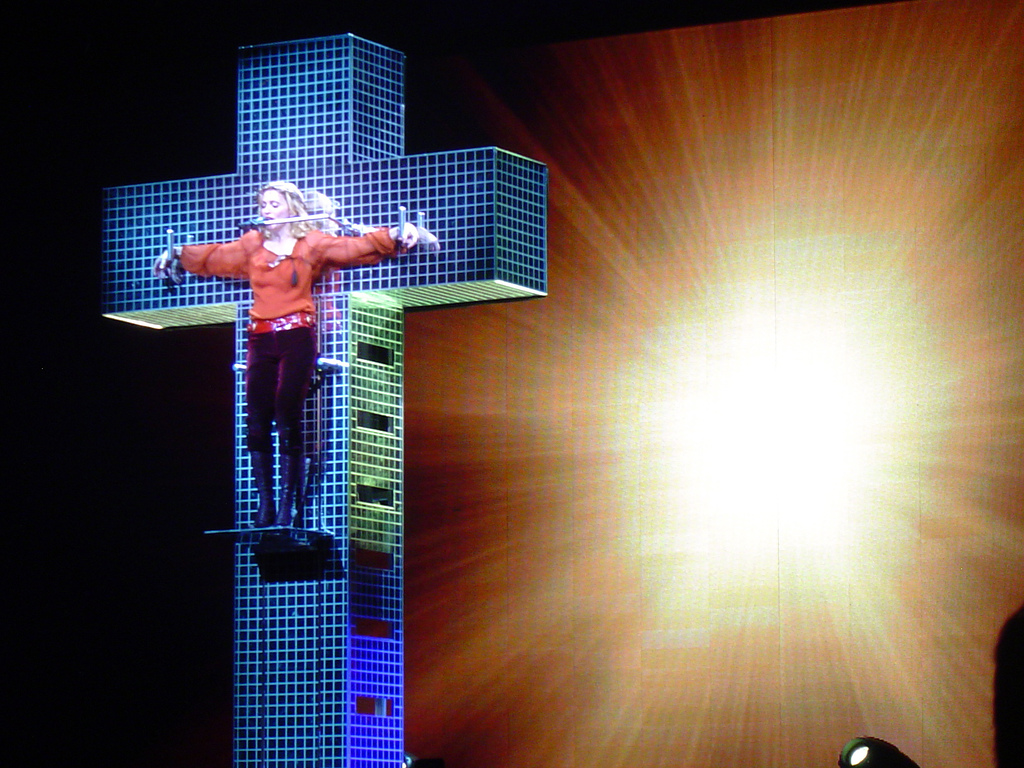

Her look for the now-legendary “Like a Virgin” performance at the first MTV Video Music Awards in 1984 was a rebellious cocktail of punk, new wave, and downtown grit: a tight bustier, lace, tulle, pearls, beads, and a giant silver cross, which defined her style for the decade. The morning after, while the Catholic Church and puritan America cried foul, teenage girls everywhere were suddenly sporting crucifix necklaces.

Just a few years later, in 1987, Princess Diana wore the Attallah Cross—a bold pendant in gold, silver, amethyst, and diamonds belonging to publisher Naim Attallah—to a London charity gala. Paired with an Elizabethan-style dress in black and burgundy with a high-neck ruff, the look cemented the jeweled cross’s place in pop-cultural memory.

Naturally, fashion houses didn’t miss the point, and everyone from Karl Lagerfeld at Chanel to Vivienne Westwood to Christian Lacroix made their own versions in the ’80s and ’90s. From their very first collections in the 1980s, Dolce & Gabbana drew on a romanticized vision of Sicily: a maximalist blend of Baroque opulence and black-clad women. Their aesthetic would hardly be complete without the crucifixes that punctuate so many of their collections.

By the early 2000s, crucifixes were everywhere. Christina Aguilera and Britney Spears made them pop talismans; 50 Cent and Eminem made them streetwear staples. From music videos to red carpets, the pendant moved fluidly between high fashion and everyday wear, drifting further from its devotional roots and settling into the role of a versatile accessory. Each decade seems to give it a new twist—and we may be in the middle of another one right now.

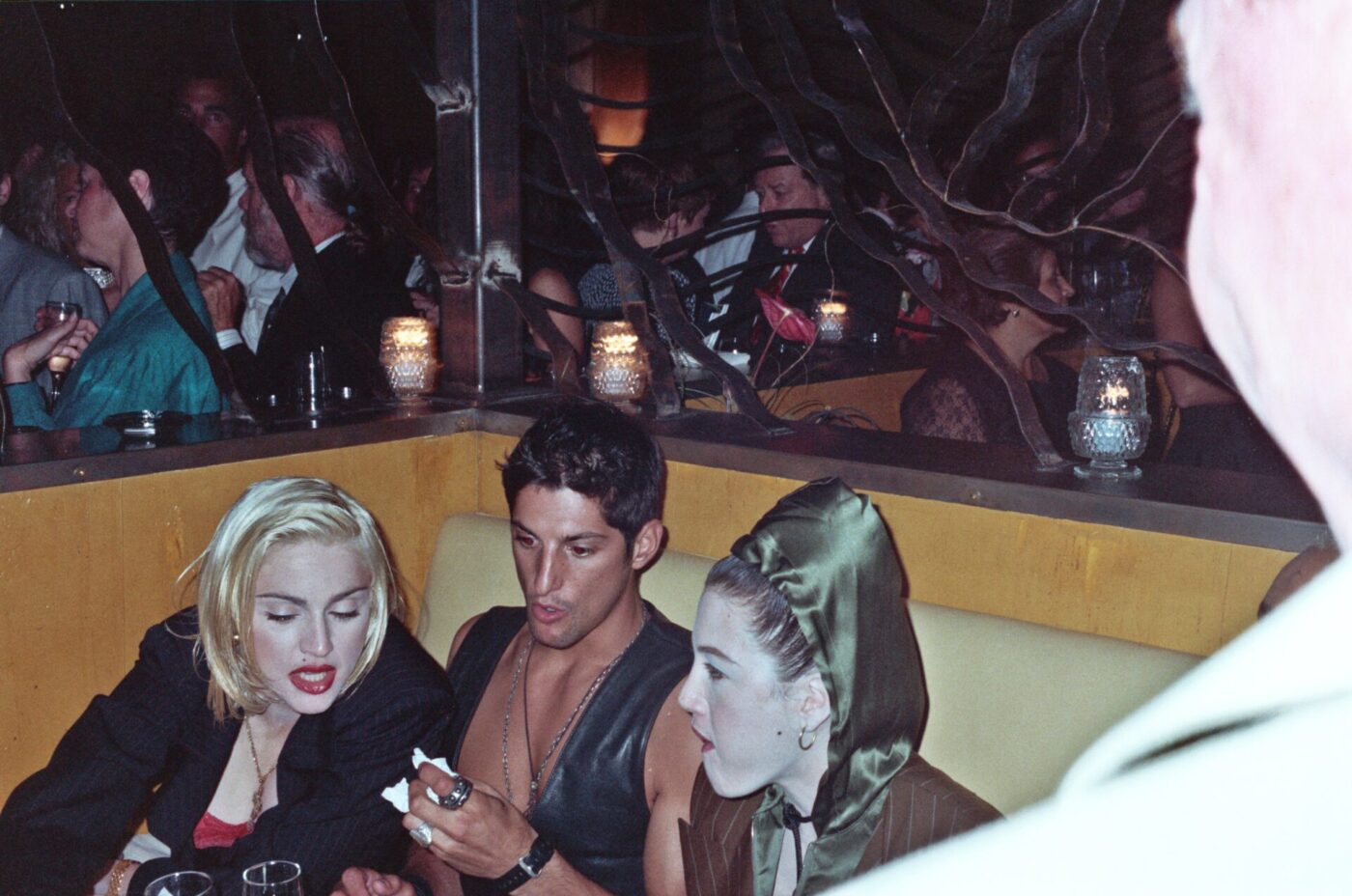

Madonna in 1990; Photo by Alan Light, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22879408

Case in point: in January 2023, Kim Kardashian bought the Attallah Cross at auction for more than $200,000. She wore it with a plunging white gown and layered pearls at the LACMA Art + Film Gala, bringing the jewel back into the spotlight. And that’s not to mention her look at the 2018 Met Gala—a custom Donatella Versace dress shimmering with two luminous crosses. The Gala’s theme—Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination—saw everyone from Bella Hadid to Miley Cyrus incorporating variations of the symbol.

But it wasn’t Madonna who started the trend—or even Elvis Presely, who wore one around his neck a few decades before the singer or Kim K did. (Ever the showman, the singer also wore a Star of David, quipping that he didn’t want to “miss out on heaven due to a technicality.”)

There’s evidence of cross jewelry from the 5th century in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum; based on archeological evidence, it’s widely believed that cross jewelry came into fashion around then, though crude wood versions have likely been worn since the 2nd century. During the height of the Roman Empire, the cross was as much as symbol of Christianity as it was a showcase of power—it was a (quite successful) instrument of mass torture, after all.

Centuries later, cross necklaces were a favorite of hyper-Catholic queens like Catherine of Aragon and Mary Stuart. Their jewelry, however, offered little protection: Catherine from her infamous divorce at the hands of Henry VIII, and Mary from the executioner’s axe. Among the children of Europe’s aristocracy, oversized crosses, coral beads, and amulets of every kind were practically mandatory, desperate charms against the continent’s stubbornly high infant mortality.

By the Renaissance, jewelers tried to outdo each other with intricate designs and embellishments on their cross jewelry, worn by elites like the Medici family, and the symbol accessorizes many paintings from this era. Then, Bram Stoker’s famed 1897 Gothic novel Dracula anointed the cross necklace as protection against vampires, drawing from accounts of the symbol warding off evil, and sending it straight into the wardrobes of the next century’s goth kids.

Portrait of Virginia de’ Medici sporting an ornate crucifix necklace

Meanwhile, far from the spotlights, Italians have worn crucifixes for generations, without much fuss. In many parts of the country, it’s still customary to give a gold chain with a crucifix or other sacred medal for a baptism or first communion. I’m fairly confident God forgave me when I sold mine to cover the cost of some particularly expensive university books. I’m less certain my aunt—the one who gifted it—would be quite as merciful if she ever found out.

Crucifixes dangling from necklaces and bracelets are just another expression of our ever-peculiar relationship with Christianity. For most of us, they belong more to popular culture and national identity than to faith—like nonna’s collection of santini (saint cards) taped to the kitchen door.

Within the Church itself, the crucifix as necklace remains central, though with very different resonances. The Pontificale Romanum requires bishops to wear a pectoral cross, a practice dating back to antiquity and once observed not only by prelates but also by priests and laypeople. Popes, in particular, have used their pectorals to project personal ideals.

Benedict XVI’s most famous cross, a gold-plated silver piece he left to St. Oswald’s Church in Traunstein upon his retirement in 2013, was stolen a decade later and remains missing, despite the thief’s conviction. Pope Francis, by contrast, chose silver over gold, a modest emblem that underscores his Franciscan-inspired mission of humility and evangelical poverty. On the day of his election, Pope Leo XIV went in the opposite direction, wearing a pectoral embedded with fragments of bone from saints tied to the Augustinian tradition.

Pope Francis wearing the silver cross

As with many things relating to the church and to fashion, crucifixes have recently entered a third sphere: Italian politics.

In May 2019, the Italian Minister of the Interior, Matteo Salvini, concluded an electoral rally of European sovereignist and far-right parties by unsheathing a rosary and “entrusting” himself to the immaculate heart of Mary. The gesture provoked unanimous criticism from the entire Italian Catholic world, starting with the Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin, who said that “invoking [God] for yourself is always very dangerous.” Later that year, Prime Minister Georgia Meloni declared in an integral speech that “if you feel offended by the Crucifix…it is not here that you should live” and “we will defend those symbols…and our identity,” framing the crucifix as not just a religious symbol, but a marker of Italian identity.

Despite being a country where fewer and fewer people attend mass, the crucifix clearly still carries a magnetic cultural charge, able to shift from sacred to profane in the blink of an eye. It’s not going out of fashion anytime soon; Vogue Italia predicted it as summer 2025’s hottest trend, and crosses of all shapes and sizes adorn as many celebrities’ necks now as in the pop music videos of last century.

There’s beauty in its ambiguity—in whichever Madonna it’s paying homage to. Sometimes it’s a statement of faith, sometimes of style, sometimes of power, sometimes of rebellion. And sometimes, it’s simply the price of an overpriced art history manual.

Which might be the point: beyond its evangelical message, the crucifix bears whatever meaning we decide to hang on it.