If you could close your eyes and picture the perfect chair—four-legged, light, impossibly sturdy, elegant but without trying too hard—it would be the Chiavarina. No excess, no frills, just a chair distilled into its purest form. And while it may seem like the unassuming workhorse of countless dining rooms, for over 200 years, the chair has been the darling of royals, the muse of modernists, and a quiet icon of Italian design.

As the name implies, the chair comes from Chiavari—a seaside town on the Ligurian Riviera di Levante between Portofino and the Cinque Terre—where, in 1807, Stefano Rivarola, president of the Economic Society of Chiavari, returned from his travels through France. There, in the opulent salons of a rising aristocracy, he had been struck by the refined lines and stately presence of Empire-style furniture. In Italy, nothing quite like it existed. Turning to one of Chiavari’s finest woodworkers, Giuseppe Gaetano Descalzi—whose silver-medal-winning chests of drawers had secured Rivarola’s confidence—he issued the challenge of creating an Italian interpretation. Rather than mimicking the heavy grandeur of French Empire furniture, Descalzi stripped the chair down, refining its structure, slimming the sections, and using only local materials.

The result was the Campanino, the first Chiavarina—a chair so simple yet masterfully constructed that it set the standard for Ligurian craftsmanship for centuries to come. The Chiavarina was light but strong, minimalist but rich. Made of cherry and maple wood from the surrounding mountains and hills, the chair’s tapered legs curved subtly at the base, giving it an effortless sense of weightlessness and elegance. Its strength, however, lay in the construction: rather than being held together with nails or screws, its components were interlocked and bonded with a hot glue made from animal bones. The seat was not attached as its predecessors had been but woven directly onto the chair, using four interlaced strips of willow bark that provided elasticity and support. The backrest, perhaps the Chiavarina’s most distinctive feature, was composed of sleek symmetrical spindles, rising from the seat to meet a gently arched crest rail. This finely sculpted detail, reminiscent of the ornamental grace of the Empire style, made a fine match with Neoclassical sensibility.

This first model laid the foundation for a flourishing local industry built on carpenters, turners, and weavers, and it did not take long for the world to take notice. By the mid-19th century, the chairs had found their way into European courts, including those of Naples, Moscow, Turin, and Vienna. Charles Albert of Savoy and Emperor Napoleon III furnished their palaces with it, while Antonio Canova praised its perfect synthesis of form and function. By the 1930s, these chairs were no longer confined to Europe; they became sought after in homes and institutions worldwide, from the White House in Washington to the Palace of Versailles, from Palazzo Reale in Genova to the Vatican.

Early Chiavarina model; photo courtesy of Eligo Studio

As the design world marched into a new era, the Chiavarina found itself in more good company—namely, the sketchbooks of Italy’s sharpest minds. Franco Albini, Ignazio Gardella, and Luigi Caccia Dominioni all slipped it into their sleek interiors throughout the ‘50s and ‘60s.

But it was Gio Ponti who, in 1957, marked the true turning point in the Chiavarina’s story. For Ponti, furniture had to be accessible—”light and strong at the same time, perfectly shaped, and affordably priced,” he said—and, ever the modernist maestro, he reinterpreted the chair by stripping away every superfluous detail. The result was the Superleggera (“Superlight” in Italian)—a chair that held true to its name. With its slender, tapered legs (as if drawn by Saul Steinberg) and weighing just 1.7 kg, it could be lifted effortlessly with a single finger. “A chair, just a chair,” as Ponti would often say—yet one that became an icon of 20th-century design, now part of the permanent collection of the Triennale Design Museum in Milan.

In turn, future generations of designers took Superleggera’s featherweight genius and ran with it. Riccardo Blumer, in 1996, made his Laleggera stackable, and Frank Gehry ditched wood for aluminum in his Superlight (2004).

The Superleggera being put to the test

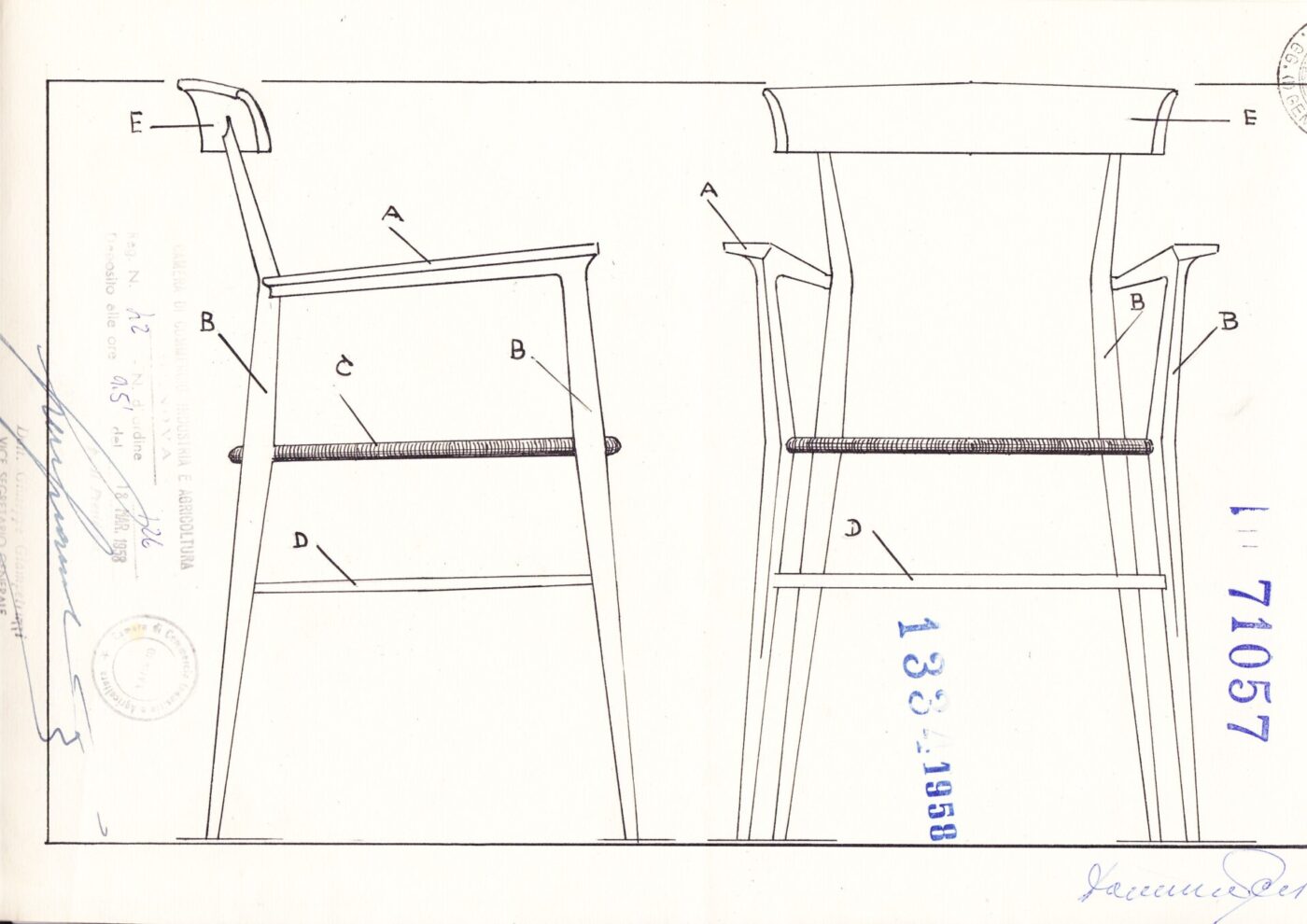

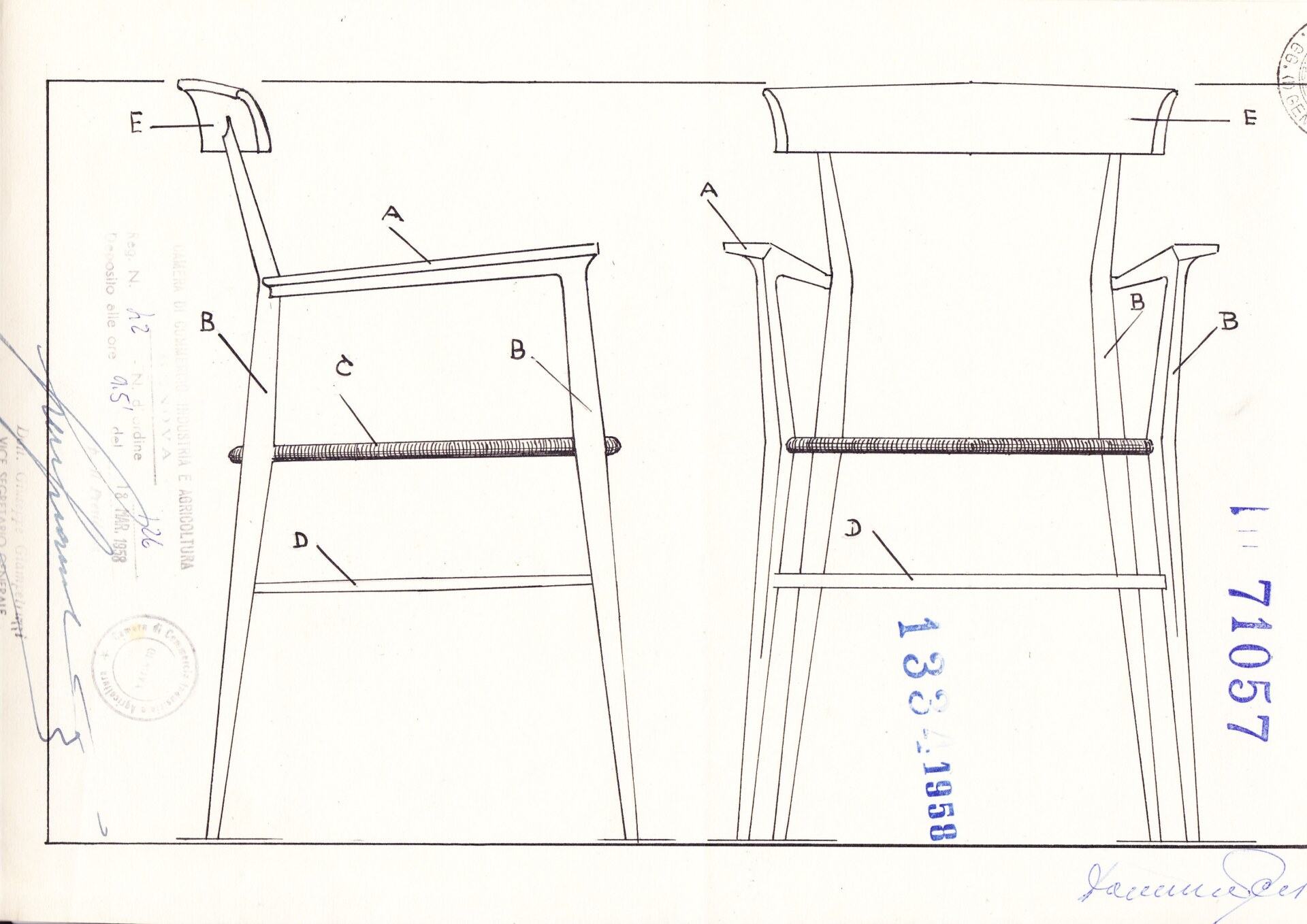

Now, after 50 years off the market, the Tigullina armchair, a variant of the Chiavarina, is experiencing a renaissance thanks to Eligo Studio. First designed in 1956 by Colombo Sanguineti for Sanguineti GB & Figlio, the chair, which is named for the coastal region of eastern Liguria that includes Chiavari itself, received an honorable mention at the Compasso d’Oro that same year and was officially patented in 1958. In 2013, Eligo Studio designers Alberto Nespoli and Domenico Rocca, the latter of which is from Chiavari, embarked on a mission to bring back the forgotten model. Their search led them to the heirs of Chiavari’s master chairmakers, including Giannina and Luisella Sanguineti, Colombo’s daughters, who provided the chair’s original drawings.

The original blueprints for the Tigullina armchair

Revived through close collaboration with these artisans—a meticulous exchange that continued until both sides were satisfied and every detail was perfected, Nespoli explains—the new Tigullina stays true to its original construction while integrating superior materials and techniques. Naturally seasoned cherry and beech ensure durability, while a hand-woven Indian cane seat enhances comfort. “We have recreated an icon from scratch,” Nespoli recounts—one that will be produced in limited editions and released slowly over time.

So, what’s the secret to the Chiavarina’s timeless appeal—and the reason the Tigullina was destined for a comeback? According to Nespoli, it all comes down to a perfect cocktail of obsessive research, historical memory, and design principles so fundamental they practically govern the universe.

“In our field, these principles are dictated by meticulously studied sections, dimensions, and proportions. Nothing is invented. We observe, analyze, and study,” explains Nespoli. The golden ratio, Fibonacci’s mathematics—the same sacred formulas that shape everything from Renaissance cathedrals to Oscar-winning cinematography—are woven into its very frame.

“This method has deep historical roots, from Michelangelo to Leonardo and, later, the great masters of the 20th century. Gio Ponti himself drew inspiration from Frank Lloyd Wright, who, in turn, was one of the most influential architects of his time,” Nespoli says. “Italian design has always evolved through continuous study and research. The closer you get to the source, the more you understand how essential these principles are to creating truly timeless design.”

The Tigullina is tangible proof—and, contrary to Ponti’s pontifications, demonstrates that, sometimes, a chair is not just a chair.

Eligo Studio's Tigullina chairs