The region of Puglia is known for many things: juicy burrata, aperitivo-staple taralli, nonne rolling orrechiette in the Barese streets, white conical Trulli houses, sandy beaches, and rows upon rows of olive trees. But there’s much more to Italy’s heel (if the above info was new to you though, get reading on the rest of our Puglia Issue here). Take, for example, the fact that the region is home to a neutral speed, circular test track that’s visible from space, spawned a dance with roots in female expression, and claims over 100 different types of local breads. Here, five things you never knew about Puglia, each more of a reason to love and explore this peninsular region.

The singer of “Volare” is from Puglia

Volare, oh-oh

Cantare, oh-oh-oh-oh

These catchy lyrics can be heard playing at every Italian American restaurant, during the intro of Woody Allen’s To Rome with Love, and with the turn of a dial on an Italian radio. From the chorus of the hit song “Nel blu dipinto di blu”, better known as “Volare”, these words have painted a clear image of Italy since their release in 1958. Though it’s been sung by over a hundred artists–among them Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles, Frank Sinatra, Luciano Pavarotti, Paul McCartney, Dean Martin, Gipsy Kings, and Tony Clifton–the original recording artist and writer is Pugliese local Domenico Modugno. Born on January 9th, 1928, in the small fishing village of Pogliano a Mare, Modugno escaped to the northern cities as soon as possible; but he never lost his southern roots, writing many of his famed songs in Pulian and Sicilian dialects with themes influenced by Puglian and Siclian mythology. But “Nel blu dipinto di blu” was unarguably his greatest hit, winning 1958’s Sanremo and topping the charts in Italy, France, the United States (the first for an Italian song), as well as elsewhere in Europe. But the biggest win came in Beverly Hills in 1959 at the first Grammy Awards, when “Nel blu dipinto di blu”, and therefore Domenico Modugno, took home the first ever Grammys for both Record of the Year and Song of the Year–that’s a lot of gold for little Puglia.

Domenico Modugno

Puglia helped create the world’s most giftable soap: Savon de Marseille

The amazingly scented, pastel colored, rounded blocks of Savon de Marseille are some of the most recognizable, and most gifted, soaps worldwide. They certainly evoke images of a blue summer on the Côte d’Azur, the lavender fields of Provence, or a stroll along the Seine, but this famed soap company actually has its origins in none other than Puglia’s port town of Gallipoli. The method of making soap with a base of olive and laurel oils comes from thousands of years prior in Aleppo, Syria; with trade and the crusades, this soap found its way to Medieval Europe, and there was no place better suited for its production than olive-tree-laden southern Italy and Spain. Soap production took hold in Gallipoli, and the inhabitants traded their soap to the rest of Europe, along with lampante oil (olive oil not up to par for consumption) from Salento. It’s this oil that was originally used as the basis for Marseille soap. Further, in his Historical Memoirs of the City of Gallipoli (1836), Bartolomeo Ravenna records that many Gallipoli locals who worked in soap were brought to Marseille, Naples, Livorno, and Genoa to begin similar production there. In the 16th century, Marseille became a headquarters of French soap production, using the techniques and often the oil from Puglia. Then, in the 17th century, King Louis XIV, in an effort to define and promote the soap’s quality, created a set of regulations for making soap under the label “Savon de Marseille”, dictating that production had to be local to Marseille, heated in cauldrons, and using pure olive oil. This still holds true today, but, when you grab a sudsy bar of Savon de Marseille, be sure to thank the Pugliese.

Photo courtesy of Vinicius Pinheiro

The author of the Zingarelli Italian dictionary was Pugliese

Those in Italy and elsewhere who claim that the Pugliese dialect is “so difficult to understand” and “so different from standard Italian” fail to recognize one thing in particular: the author of the famed Zingarelli Italian dictionary–referred to across the country and still published and updated annually by the Zanichelli publishing house–is from Puglia. Nicola Zingarelli was born on August 28th, 1860, in the northwestern Puglian town of Cerignola. His elementary education was in this city, and by the age of 10, he had received a medal for scholastic merit from the Decurionate of Cerignola. After high school and university in Naples and further studies in Florence and Berlin, Zingarelli moved back to Italy and began working on his most famous project, the Vocabulary of the Italian language. Published in installments beginning in 1917, Zingarelli completed five editions before his death in 1935. It’s not just a normal dictionary: Zingarelli’s work created space for the entire panorama of literary Italian, paying attention to dialects as well as varying forms of current use. Today, the name Zingarelli is still synonymous with modern Italian vocabulary, even if words like ghimmone (too much to eat) and dambònde (over there) stay strictly Pugliese.

Brindisi was the capital of Italy for six months

Rome hasn’t always been Italy’s capital. The monumental city wasn’t the first choice after unification, which went to Turin, or even the second choice, which went to Florence. In 1871, however, the seat of power did move to Rome, where it’s remained to this day–more or less. We all know of Italy’s controversial choices during the first half of WWII, but, after the Italian army signed an armistice with the Allies, the country faced German occupation much like the rest of Europe. Fearful of being detained, the royals fled their home in Rome in a panic, traveling south and surprising the locals when they arrived for a stay in the small Pugliese port town of Brindisi. Here, King Vittorio Emanuele III, his wife Queen Elena, Prince Umberto, and the head of government Badoglio, along with other ministers and military officers, took up residence at the Swabian Castle from September 10th, 1943, to February 11th, 1944. For these six months, the country and military–both of which were in bad shape–were run from Brindisi. The salt air did some good for the latter, and some sense of military reorganization did occur; late, per usual, as Allied liberation began soon after, moving the royals north to Salerno (which was the capital from February 12th to July 17th, 1944). After that, life in Brindisi went on as normal–but residents will always have a bit of bragging rights.

Photo courtesy of Valerio Giannattasio

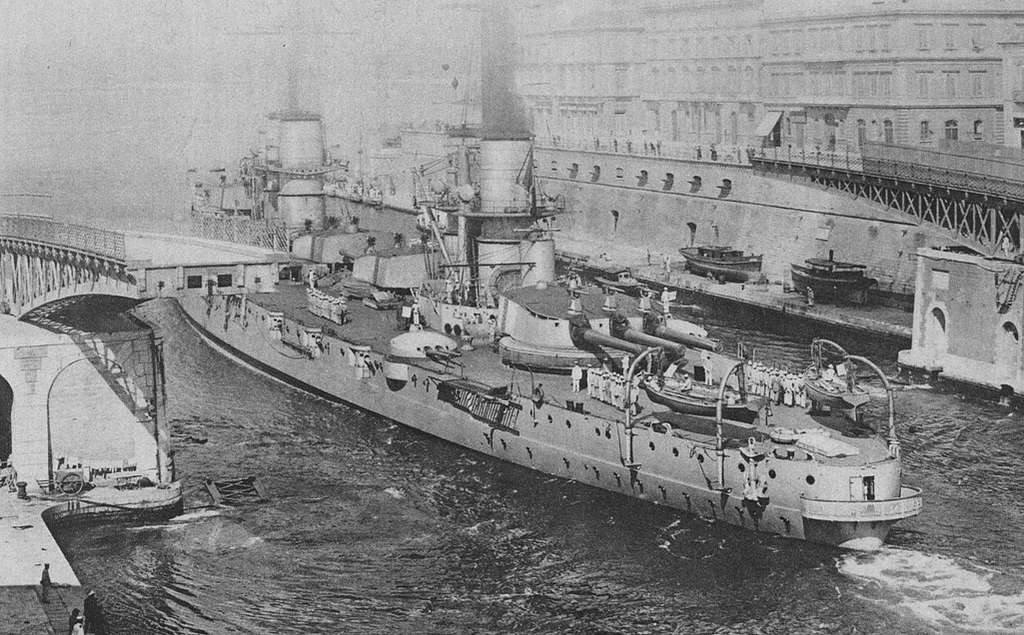

The Battle of Taranto informed Pearl Harbor

On the eve of November 11th, 1940–five months after Italy declared war on Great Britain–21 obsolete biplanes took off from the British aircraft carrier Illustrious with one target: the Italian navy ships stationed at the Taranto Naval Base. Italy’s potent collection of naval ships was of utmost interest and concern to Great Britain–for they had the power to dominate the Mediterranean and close off the Suez Canal–and they all happened to be stationed in Taranto. Only two waves of British pilots made it to the base due to bad weather, and, though they were met with resistance, were able to severely damage much of the fleet and inflict nearly 700 casualties. From this moment on, power in the Mediterranean shifted, and the Italian navy never again challenged another naval force. Word of the attack spread, and the U.S. Navy realized their Pearl Harbor was equally as vulnerable as Taranto. They suggested implementing torpedo nets, but were slow on the draw due to bureaucratic minutia. The Japanese army, however, also studied the attack; and they did take action, carrying out a similar offensive on December 7th, 1941.

Battleship Dante Alighieri in Taranto in 1917