Wins at the Olympics & Paralympics

What a summer! With 402 competitors in 30 sports, Italy ranked 10th in overall medals from the 2024 Paris Olympics, taking home 39 in total: 11 gold, 13 silver, and 15 bronze. Women’s events brought the most golds, including fencing, judo, sailing, tennis, gymnastics, cycling, and volleyball, when the team edged out both the US and Brazil to claim the championship. Italy placed gold in two mixed competitions–shooting and sailing–and three claimed the prized medal in the male divisions of canoeing and swimming (plus the latter team received a lot of thirst-trap TikTok attention). At the 2024 Paris Paralympics, Italy’s 141 competitors in 17 different sports claimed 71 total medals–24 gold, 15 silver, and 32 bronze–ranking 6th overall. Swimming saw the most golds (16!), followed by athletics (4), table tennis (2), cycling (1), and archery (1). 110 medals total between the Olympic and Paralympic Games is certainly something to be celebrated.

Claudio Stecchi; Photo by Aeltegop

Progress in Sustainability Initiatives

As numbers for the year start to roll in, Italy is topping the charts in terms of sustainability efforts. The country’s goal is to be completely carbon neutral by 2050, and “is on track to reach its 2030 targets for emissions reductions and energy efficiency,” according to the International Energy Agency. Further, the Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research declared that “Italy shows higher transformation efficiency and lower energy intensity than the biggest European Countries.” A large part of this comes from offshore wind farms in Sardinia, which have been in the works over the past couple of years and are set to continue over the next couple of years. Plus, the first six months of 2024 saw a historic record on a half-year basis: 43.8% of Italy’s energy demand was covered by renewable sources, compared to 34.9% for the first six months of 2023, according to Terna. Further, a sustainability initiative in a collection of 13 hospitals in Emilia-Romagna (known as AUSL Romagna) became one of the three finalists in the 2024 European Sustainable Energy Awards. Their actions–including new boilers, new windows, LED lighting, solar panels, etc.–allows these hospitals to self-produce more than 80% of their energy consumption, and has reduced their overall consumption by a colossal 30%.

Sardinia, seen from the sea

Relaunch of Giò Ponti’s Arlecchino Train

Originally built to commemorate the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome, the Arlecchino Train was retired in 1986 and later fully restored in 2015–but it was this year that it actually became a functioning rail line again. The train is stationed in Milan and rentable for a pretty penny, but is open to the public on some lines between northern Italian cities a few times a year. First-class only, the four-carriage train is adorned with cushy armchairs, a bar with snacks and coffee served in dainty cups, and two belvederes with panoramic windows and swivel seats. The multi-colored interiors inspired the train’s name–meaning “Harlequin”–and were conceived by star architect Giò Ponti and designer Giulio Minoletti. One of the most exciting details is that you can go all the way to the front of the train to sit where the conductor normally would, giving the illusion that you’re driving the train–but never fear, for the conductor’s cabin is actually directly above. Outside is a stark contrast to the inside, with a cartoonish, submarine-like shape that’s silvery gray with green and red accents. The renovation is part of a larger effort by Fondazione FS to promote slow tourism, and similar models–like the 1953’s ETR 300 Settebello, the 1957’s ETR 220, and the 1988’s ETR 450 Pendolino–are expected to follow suit. Check the Fondazione FS official website for up-to-date information about this train’s schedule as well as to buy tickets.

The Arlecchino Train

Finds in Pompeii

Archaeologists have made a haunting new discovery over the summer in the ruins of Pompeii: two skeletons, a man and a woman, frozen in time by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. Found in what was likely a temporary bedroom, the pair sought shelter from the falling pumice, only to be tragically crushed by the lava flow when the room’s seal trapped them inside. The woman was discovered surrounded by treasures–gold, silver, and bronze coins, as well as intricate jewelry–offering a glimpse into the wealth and daily life of Pompeii’s residents. This discovery comes in a region rich with recent finds and is part of an ongoing excavation that has revealed a “Blue Shrine” and vibrant frescoes depicting scenes from the Trojan War. It’s crazy that nearly 2,000 years later, these discoveries still give us a glimpse into what life was like–and if there’s one thing that prevailed, it’s amore all’italiana.

Pompeii, August 9th, 1967; Photo by Joost Evers / Anefo

New English Translations of Italian Authors

Your 2025 reading list is about to get a makeover thanks to a whole host of Italian books–from classics to newer works–that have been translated into English, extending the books’ potential readership by a whopping 18x. Journalist Jamie Mackay is always in the know when it comes to English translations, and we’ve gotten many great recs from his “This Week in Italy” substack newsletter, including the following. To start, Elsa Morante–who already achieved international fame with her novel La Storia (History, 1974)–hits international shelves again thanks to a translation by Jenny McPhee, who is one of the most renowned Italian to English translators of today. Morante’s 1948 novel Menzogna e sortilegio (Lies and Sorcery) is a dense, 800-page family saga rich with love triangles, social commentary, and intricate prose, written during her Sicilian exile in WWII. Morante claims she put “all of her life’s experience to that point into it”, and reading it certainly is a hefty, but rewarding, undertaking. If poetry is more your thing, grab a copy of Jolanda Insana’s collection La tagliola del disamore (Slashing Sounds, 2005), translated by Catherine Theis and published by Chicago Press’s Phoenix Poets. Born in 1937 in Sicily and died in 2016, Insana is one of the best Italian poets of her era, with fiery prose, classical allegory, and beautiful concreteness. Next is a new book in Italian markets as well: Maddalena Vaglio Tanet’s Tornare dal bosco (Untold Lessons, 2023), published in English by Pushkin Press. The story is a powerful exploration of female identity amidst a patriarchal society, told through Silvia, a reclusive teacher who retreats into the forest after her student’s tragic death; the book earned Tanet a coveted nomination for the Strega Prize. Last comes a translation that also feels rather timely, although originally published in 1960: Dino Buzzati’s The Singularity (Il grande ritratto). Translated by Anne Milano Appel and published by The New York Review of Books, the sci-fi thriller follows a professor who is mysteriously whisked away to a secluded research center for a covert mission on AI’s societal impact–and it takes on an even eerier tone in this day and age.

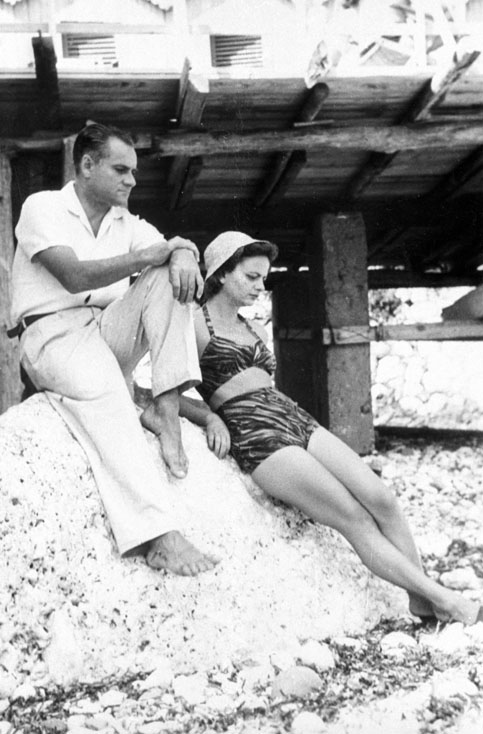

Alberto Moravia and Elsa Morante in Capri in the 1940s

And that’s not to mention…

- 23-year-old Jannik Sinner, from San Candido in the Dolomites, won the U.S. Open (among many other competitions)

- Italy defeated the Netherlands 2-0 to retain their title in the David Cup

- EDI Effetti Digitali Italiani, an Italian visual design company, took home the Emmy in “Outstanding Special Visual Effects In A Single Episode” for Ripley

- The first non-American chef to cook dinner at the Emmys was Italian