Cortina d’Ampezzo was known as a stylish resort well before hosting the 1956 Games, although the event, which was the first Winter Olympics televised live (and the first Olympics hosted on Italian soil), brought the Dolomite mountain retreat a level of renown that has endured to this day. It was the event that provided Italy a peerless world-wide platform for highlighting the country’s post-WWII economic boom and exuberant glamour, turning out a flock of European aristocrats (several heading their country’s athletic delegations) along with such celebrities as Sophia Loren for a dose of Cinecittà luster.

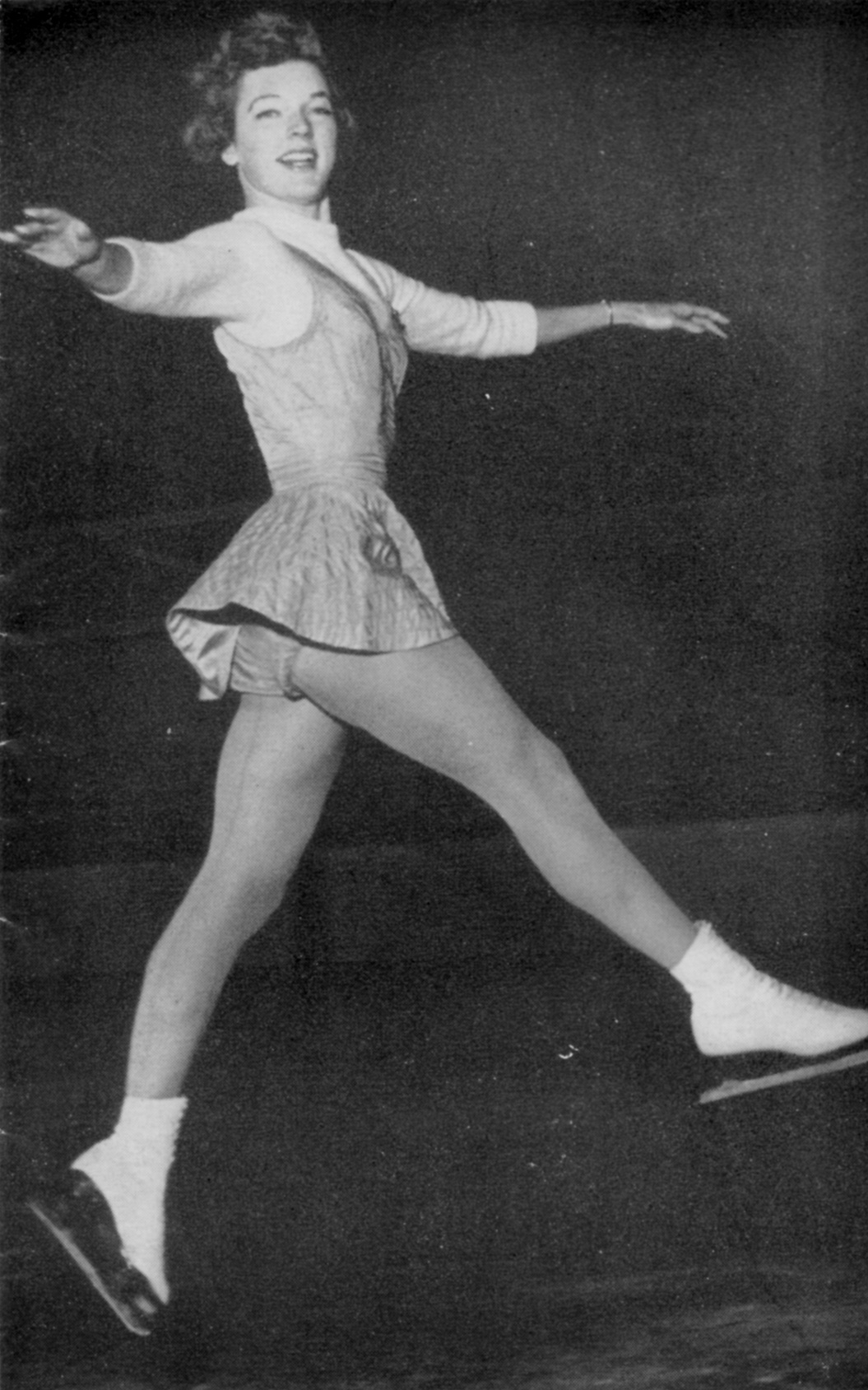

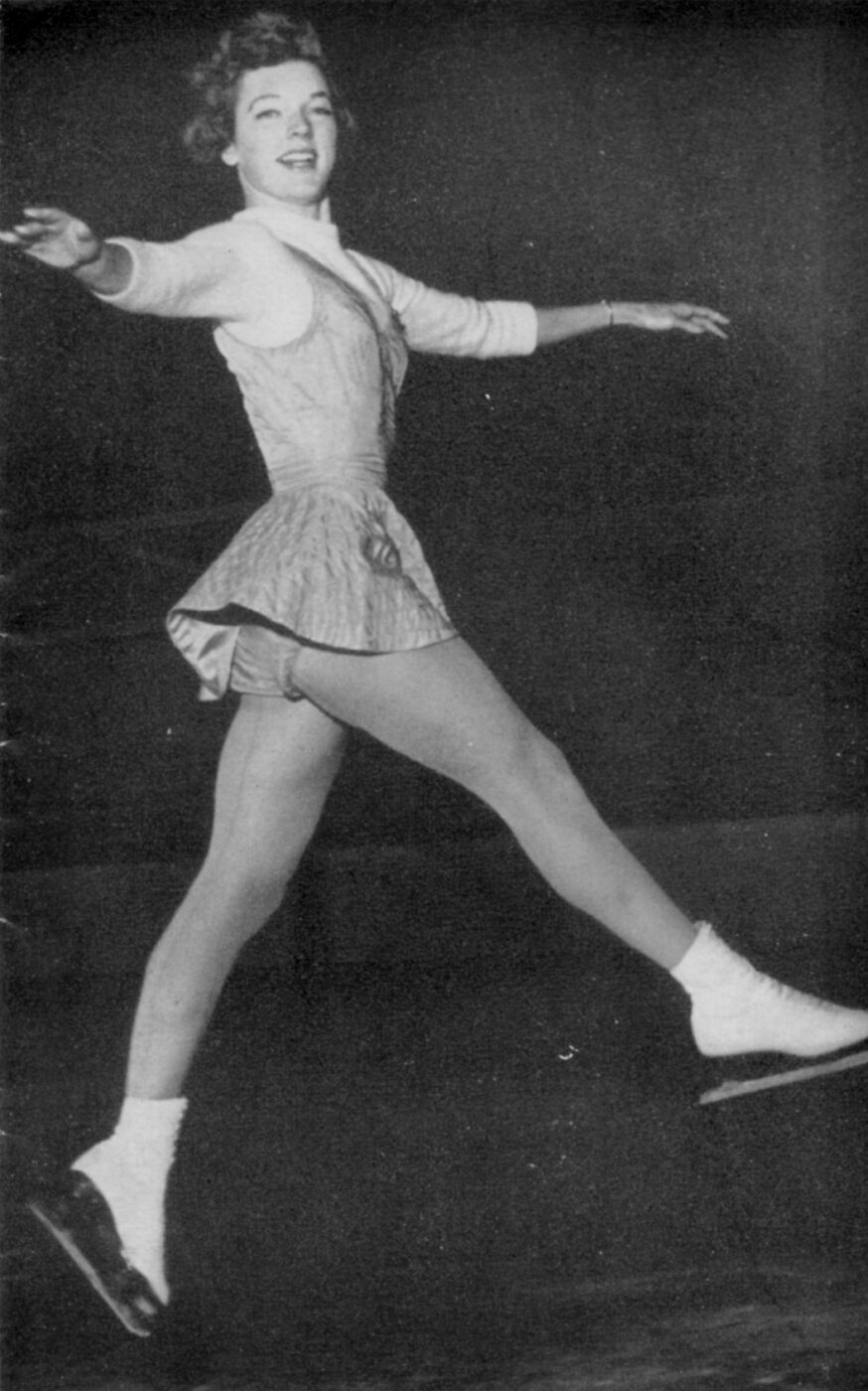

But the real stars were (as they always are) the athletes, and in ’56 the biggest names were Tony Sailer, the Austrian ski whiz who dominated all Alpine racing events, and Americans Hayes Alan Jenkins and Tenley Albright, who won gold medals for men’s and women’s figure skating, respectively. Albright’s win marked the first time an American woman took home the top prize in a sport that had been dominated since its Olympic inception by Europeans and Canadians. Seven decades after her historic win, Albright plans to be at the Milan-Cortina Games (February 6th through 22nd, 2026). In a recent interview from her home in Boston, she spoke to Italy Segreta about the competition that made her a legendary figure in sports history.

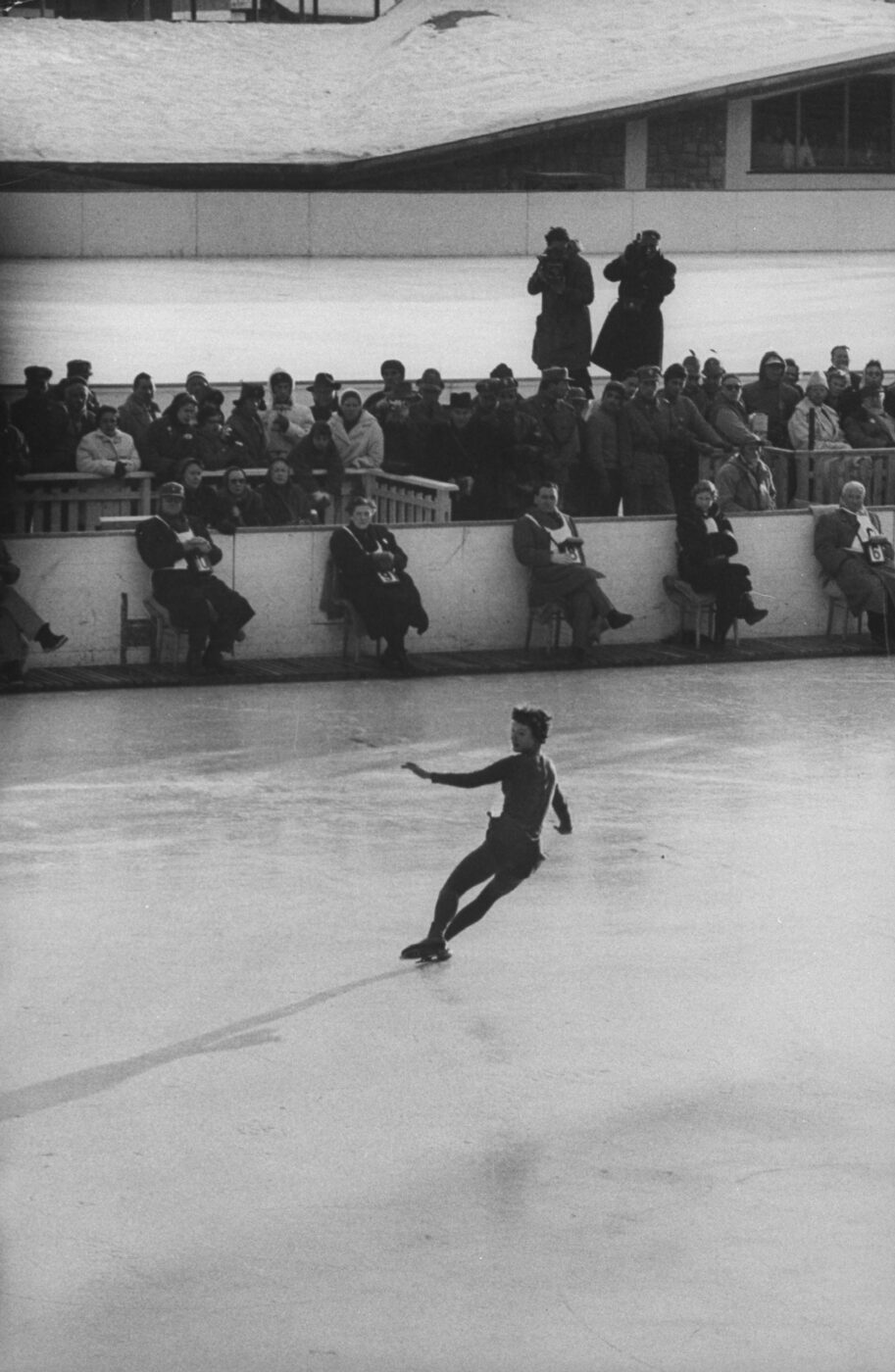

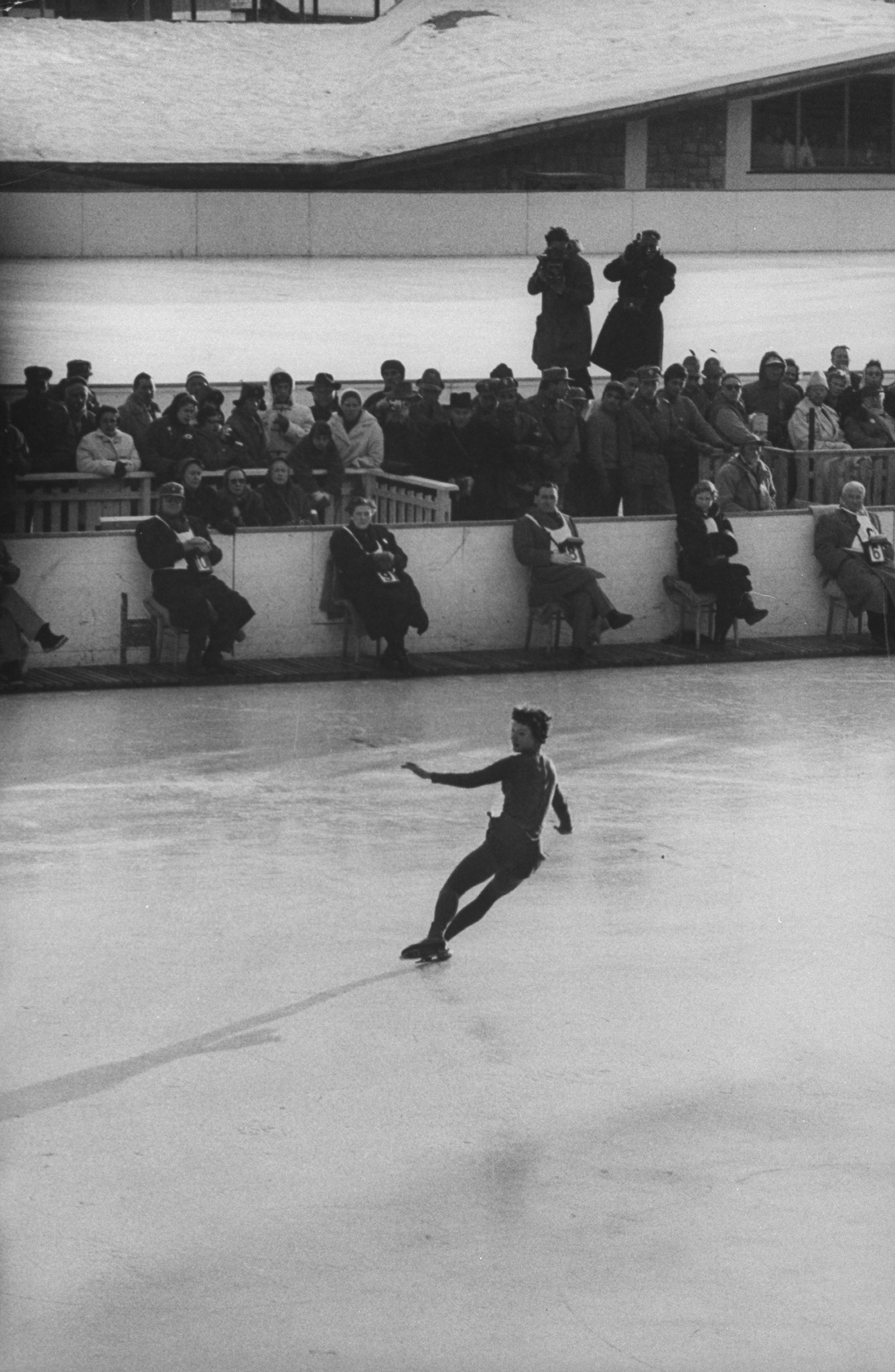

Tenley Albright, performing intricate figures, alone on the ice, before judges and spectators in stands, at Winter Olympics. (Photo by James Whitmore//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

The Olympics are as much about the personal stories and dramas behind the journey to the podium as the scoreboard results, with athletes overcoming countless competitive, physical, and financial obstacles to get a shot at their sport’s ultimate accolade. Like the great track-and-field star Jesse Owens, who won four golds during the 1936 Games held in a hostile Nazi Germany, and speed skater Dan Jansen’s comeback win after years of near misses and family tragedy in his fourth Olympics in Lillehammer.

For Tenley Albright, though, the ’56 Cortina competition looked as if it would provide a smooth glide to victory. When she arrived in the Dolomites a week and a half before the Games began, she was the favorite to win gold—Albright had racked up two World and North American championships and four (ultimately five) U.S. titles, and was a seasoned Olympian, having taken the silver in the 1952 Games in Oslo.

But winning in Cortina wasn’t as sure a thing as it might have seemed. Albright was diagnosed with polio at 11 years old, a setback requiring a lengthy hospital stay that generated fears she might not walk again. Fortunately, the disease turned out to be a temporary reversal. “When the doctors told my parents I was no longer contagious, and that it would be good if I did something I liked doing before but wasn’t with other children, skating seemed to be the closest we could get to that,” she says. “I remember the first time I went back to the skating club and had my hand on the barrier, and hand over hand just slowly went down the ice. The more I went there, the more I loved it.”

While her polio was well in the past when she traveled to Cortina, Albright suddenly found herself facing a new physical challenge. Like other athletes, she had planned an early arrival to acclimate to the town’s altitude (1,224 meters) and to the reality of competing outdoors (the ’56 Winter Olympics were the last time skating events were held in an open-air setting). “We had to get used to skating in the snow, the cold, even the rain,” she recalls. “One big thing was the wind. I remember coming out of a spin ready to take the next steps, and I was already at the other end of the rink because of it.”

Outside skating provided even more treacherous obstacles than wind and snow. Albright was immersed in pre-competition practice when she skated into a disaster that put her chance of competing, never mind medaling, severely at risk. “I was trying to stay out of the way of a skater who was being photographed, swerved, and went into a deep rut in the outdoor ice. I fell down and the heel of one skate went into the ankle of the other foot.”

Albright was used to being injured as a competitive skater—“[Getting] black and blue is normal, because every time you want to learn something new, you have to start [by] falling down”—but her ankle was cut to the bone. Her father, a noted Boston-area surgeon, flew immediately to Cortina to treat his daughter’s wound.

Although she could bear weight on the injury after a few days, the pain persisted constantly leading up to the free skate. In practice, right before her performance, she tried a waltz [half rotation] jump. “I fell flat, and that was a shock.”

Maybe it was because she had once fought a bigger health battle, or maybe she was tapping into some of New England’s much-vaunted spirit of Yankee grit, but Albright was determined to meet her moment and took to the rink thinking, “I may not be able to get off the ice afterwards, but somehow I’m going to get through my program.” Disaster nearly struck again when the head of a professional ice show reached out to kiss her right as her name was announced. “I was horrified,” says Albright. “They were very strict in those days. If you were seen talking to anyone in the professional shows, it turned you professional [which would have been grounds for disqualification]. Luckily, I hadn’t spoken with the man before. We had to be very careful.”

As the music started, she remembers trying to concentrate on the Dolomite scenery to ease the pain. Albright skated to music from Jacques Offenbach’s opera, The Tales of Hoffman, like the “Barcarolle”, a transporting melody that was well-known among European audiences. (Particularly in the Veneto, where Cortina is located; a barcarolle is a type of gondolier folk song.)

“Those watching in the stands began humming and singing along to the music,” says Albright, “and that really lifted me.” The impromptu chorus must have helped—if you watch a YouTube clip of her free skate, you see Albright nailing her jumps and final spin without a wince, a performance which earned first-place ranking from 10 of the 11 judges. Earlier, she had won the compulsory, or school-figures portion of the competition, once a key part of a skater’s final score. (Compulsories required precision skating to retrace various geometric figures etched on the ice. They were abolished in 1990. Today, skaters perform a short and long program requiring certain technical elements.)

A few days later, Albright returned to the Stadio del Ghiaccio to pick up her prize, although the awards ceremony held another, although far more manageable, surprise. Joining her on the podium were teammate Carol Heiss, who had earned the silver medal (and would go on to win gold in the 1960 Olympics), and Austrian skater Ingrid Wendl. “I wasn’t prepared for the ceremony to be so moving, to see our flag go up for me,” says Albright, who remembers the beauty of the lit mountains at night and standing on a large platform in front of the Olympic flame. But when the music played for the traditional flag raising, it wasn’t the American national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner”, but rather, “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” (which served as the U.S. anthem until 1931).

Considering all the setbacks she had faced to get to the podium, Albright found the music mishap a minor, if somewhat humorous, glitch. She hugged her two competitors before receiving her medal, which was carved with an image of Nike, the goddess of victory, and the Olympic rings on the front side; the back displays an ice crystal and Mt. Pomagagnon, a Dolomite mountain near Cortina, along with the famous Olympic motto—Citius, Altius, Fortius (Faster, Higher, Stronger).

Albright stayed in Cortina for only a few days after the final ceremony—she had to get ready for the world championships, and eventually return to her studies as a pre-med major at Radcliffe, then the women’s college of Harvard University. Adding to her success story, Albright managed to balance a challenging college curriculum with her skating career. She almost makes it sound easy. “I purposely tried to do my lab courses in summer sessions,” she says, adding that she scheduled skate time before classes. “If I called [the rink] after 10 o’clock at night and they hadn’t filled the ice for hockey [practice] at four of five the [next] morning, they’d let me come and skate. I learned where the key to get in and the switch to turn on the lights were and had the place all to myself.”

After just three years of college, Albright went to Harvard Medical School (where she was only one of five women in her class). She never skated professionally, foregoing lucrative performance contracts, choosing instead to become a doctor like her father. She practiced as a general surgeon in Boston for more than two decades. Albright has also sat on boards like the Bloomberg Family Foundation and founded MIT Collaborative Initiatives, which takes a multi-disciplinary approach to studying ongoing social issues. In addition to serving as the first woman officer of the USOC, she was appointed chief physician for the U.S. Winter Olympic team in 1976. She has been inducted into many Halls of Fame (U.S. Olympic and National Women’s, to name two). The Skating Club of Boston, where she began her career, named its main rink, the Tenley E. Albright Performance Center, in her honor.

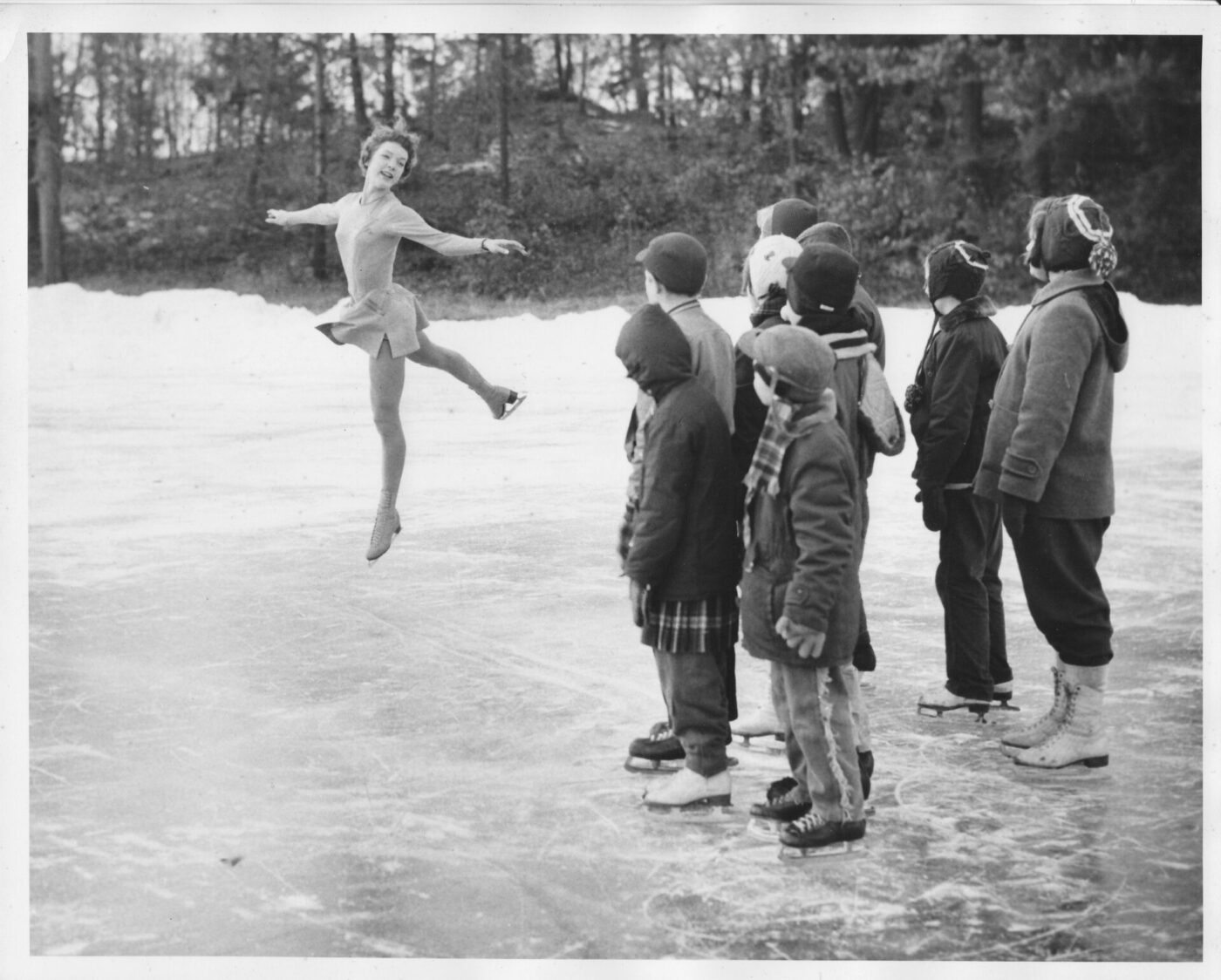

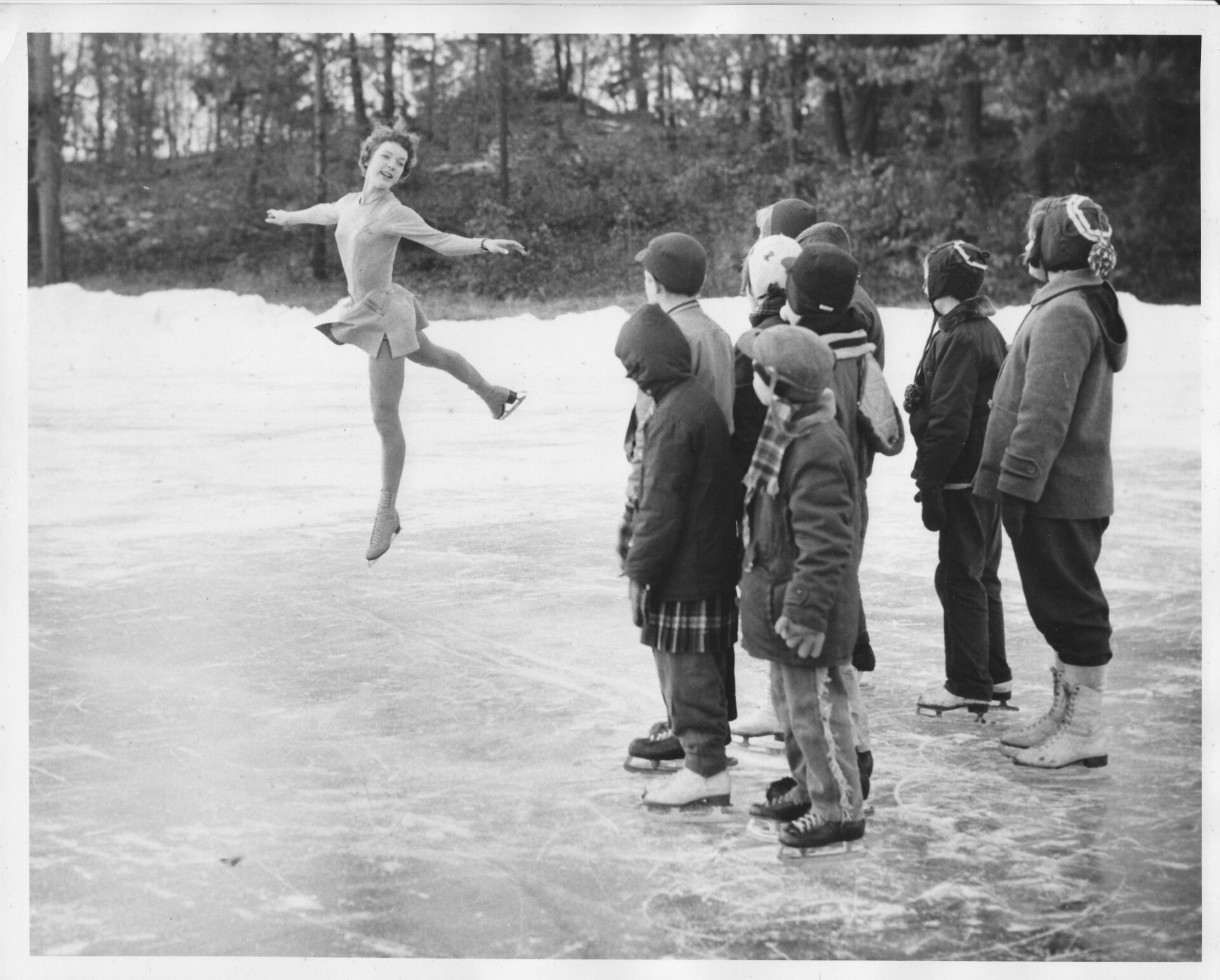

Photo courtesy of Tenley Albright

Today, Albright has turned her sights to Italy again for the next Games. “As soon as you walk into an Olympic village, you realize, ‘I’m here with so many people I don’t know, from different countries.’ But we feel that we [all] know each other.”

Although Albright doesn’t take to the ice anymore, she still imagines herself performing jumps and spins. “When you hear the music, you want to take off and do everything you ever could.” She says she skates vicariously through a daughter, who runs the Joy Skate production company, and when she’s dreaming. “I stay up in the air as long as I want and do as many turns as I want.” When she takes her seat rinkside at the Milano Ice Skating Arena (where competition for the five medal events are scheduled), she says she’ll also be “out there on the ice, in my head and my heart with all the skaters of the Olympics. That’s really going to be fun.”