I’ve been proud of my Italian heritage for as long as I can remember. With a thriving community of Italians in Canada, it was easy to remain connected to my roots, and my early years saw me, at school, boasting to any and all classmates who would listen about my Italian fluency. It was a brag, however, of which I was humbled anytime my nonna would tune into her favorite Italian soap operas and variety shows. I had no clue what anyone was saying–and not because I had a childish hubris, but because, like many Italian-Canadians, I later learned, I was actually speaking Italiese, a linguistic hybridization characterized by anglicized Italian words and italianized English words. Think garbíggio, to mean garbage, rather than the Italian rifiuti or spazzatura. Or bega (shopping bag) to the Italian busta.

Italiese can vary slightly between families and from one city to another; unlike in Toronto, you’ll hear a French influence in Montréal, with words like nous in place of noi (we) or vous instead of voi (you, plural). And, given that Italiese isn’t a standardized language, it’s tough to say exactly how many people still speak it today. But a growing number of sources indicate that it faces a decline in favor of standard Italian.

The term “Italiese” was first coined by University of Toronto linguistics professor Gianrenzo Clivio in 1975. Though not a de facto language, it’s a style of speaking, he pinpointed, born among Italian immigrants to Canada in the 1950s and 1960s. Most came to the country from rural regions of southern Italy and settled in larger cities like Toronto, Montréal, and Ottawa. This often meant that many had little to no knowledge of the standard Italian language, instead speaking the languages or dialects of their home regions or towns. With their new lives came unfamiliar foods and objects, and, in many cases, there were no words to describe these concepts in their native vocabulary. Though even if a word did exist, communication between other Italian dialects was similarly complicated. A native Friulano speaker would struggle to understand someone speaking in Calabrese, and vice versa. Italiese allowed these barriers to be broken down, using newfound English vocabulary in conjunction with whatever limited knowledge of standard Italian these immigrants had. The result was a parlance composed of basic Italian, sprinkled with words of English origin, and spoken, of course, with an Italian pronunciation.

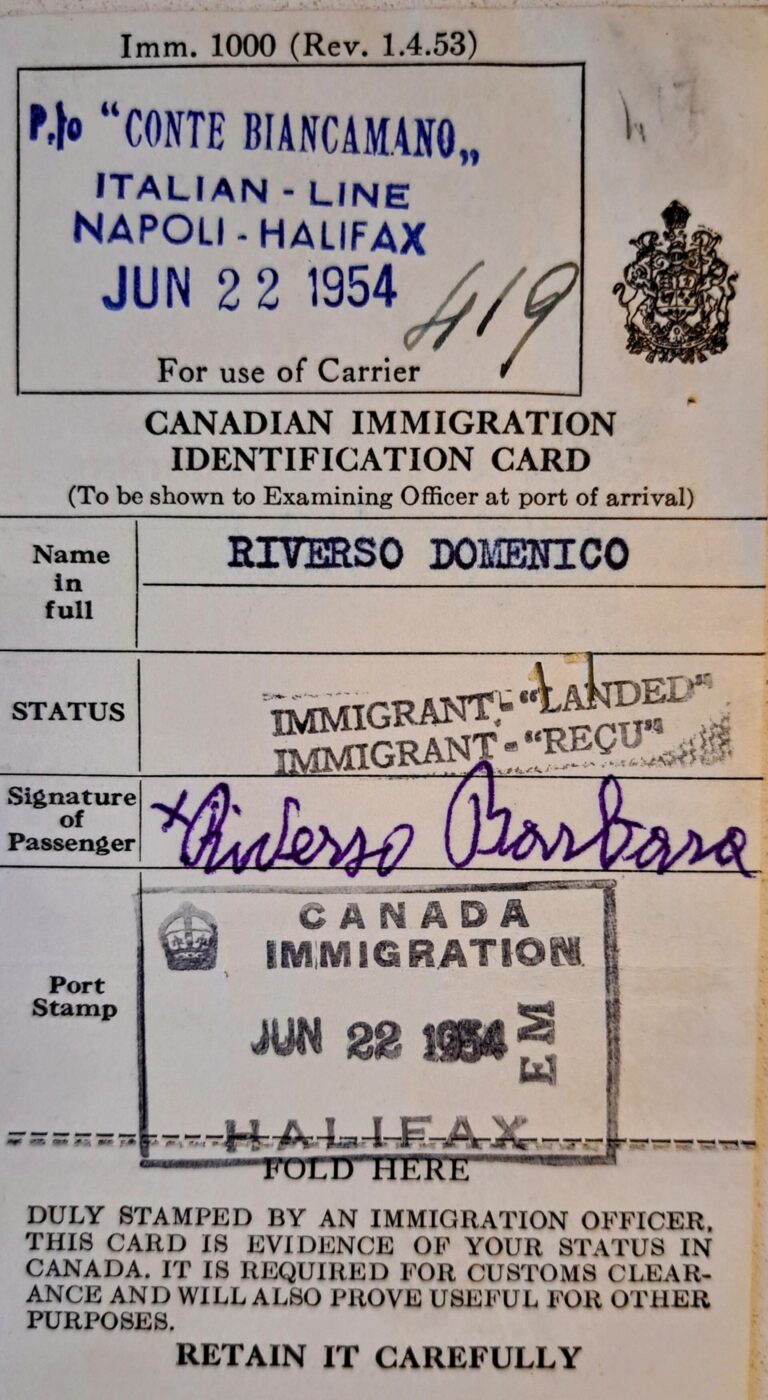

Canadian Immigration Card for passengers of the Conte Biancamano, 1954

A perfect example is the Italiese word for peanut butter: pinaburra (you can imagine the difficulty of pronouncing the novel word “peanut butter” with a heavy Italian accent). Peanut butter was a newfound ingredient upon arrival in Canada, absent from grocery store shelves in Italy at the time of these immigrants’ departure. Creating an alternative phrase using the Italian word for “peanut” proved as difficult as pronouncing the name of the nutty spread in English, as many didn’t know the Italian word arachidi, but rather the version in their mother dialect. And so, pinaburra was born and remained favored even after the birth of an Italian burro di arachidi. (Some may find it comical, but it’s certainly not as funny as “sonamabeitch”).

Italiese also helped Italian immigrants bridge a gap closer to home. Like many second-generation immigrants, their children adopted new customs as they attended Canadian schools and integrated into Canadian socio-cultural life, and food, as it often is, was at the forefront of these cultural shifts. For most children of Italian immigrants, lunch consisted of a panino with deli meats. But their tastes began to shift as they watched their classmates eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on sliced bread. Wanting to fit in, they began pressuring their parents to pack them similar lunches. But, again, sandwiches on sliced bread were not popular in Italy when their parents had left (the word tramezzino now exists, but was a foreign concept to many at that time). In the absence of an Italian word, “sanguiccio” was born after hearing their children use “sandwich”. Sanguiccio remains a popular word and is the preferred choice of both young and old; it’s particularly prevalent in Ottawa’s Little Italy, where a sandwich shop bears this name.

The Italian Canadian Recreation Club at Davenport Rd. And Dufferin Ave.

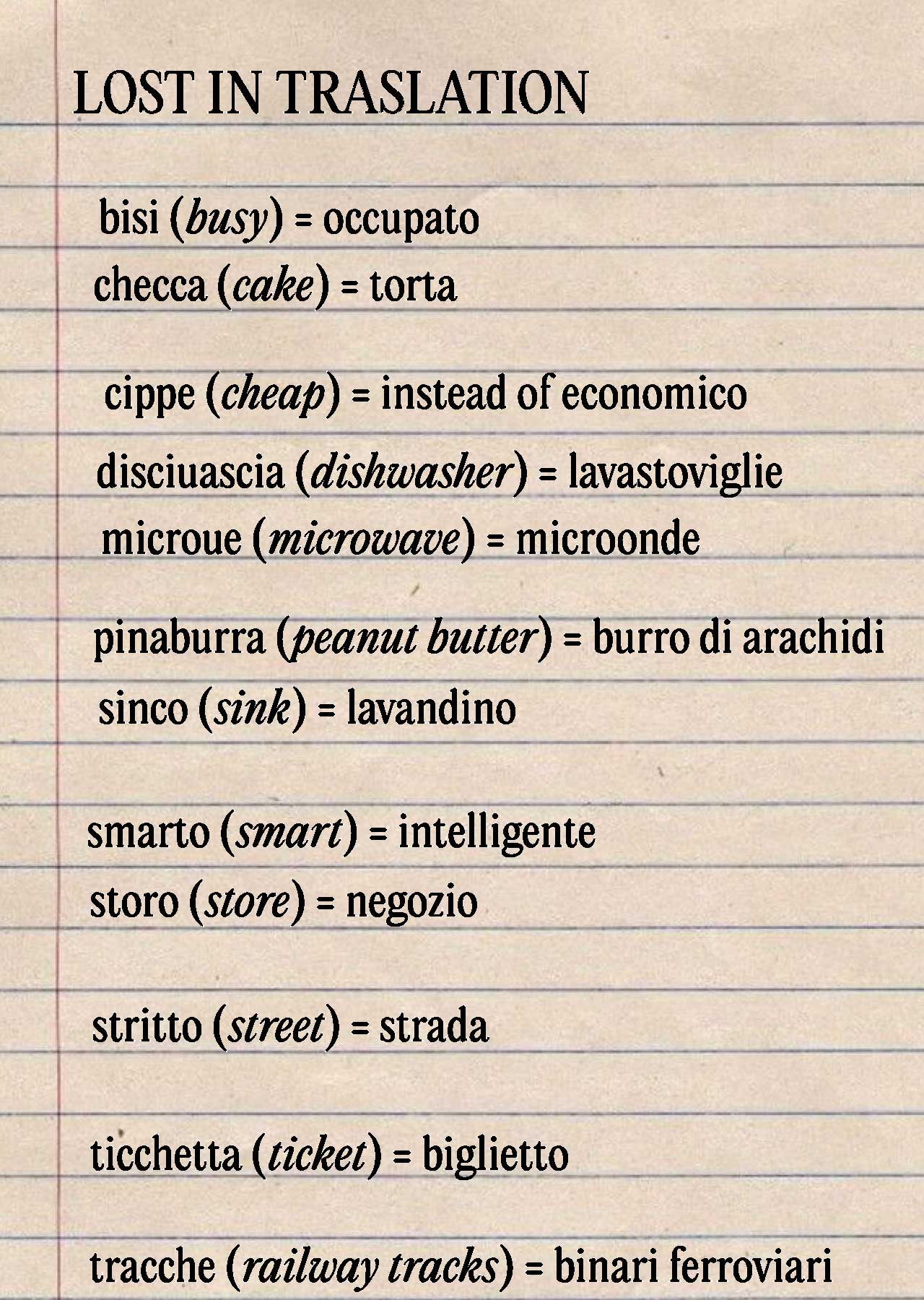

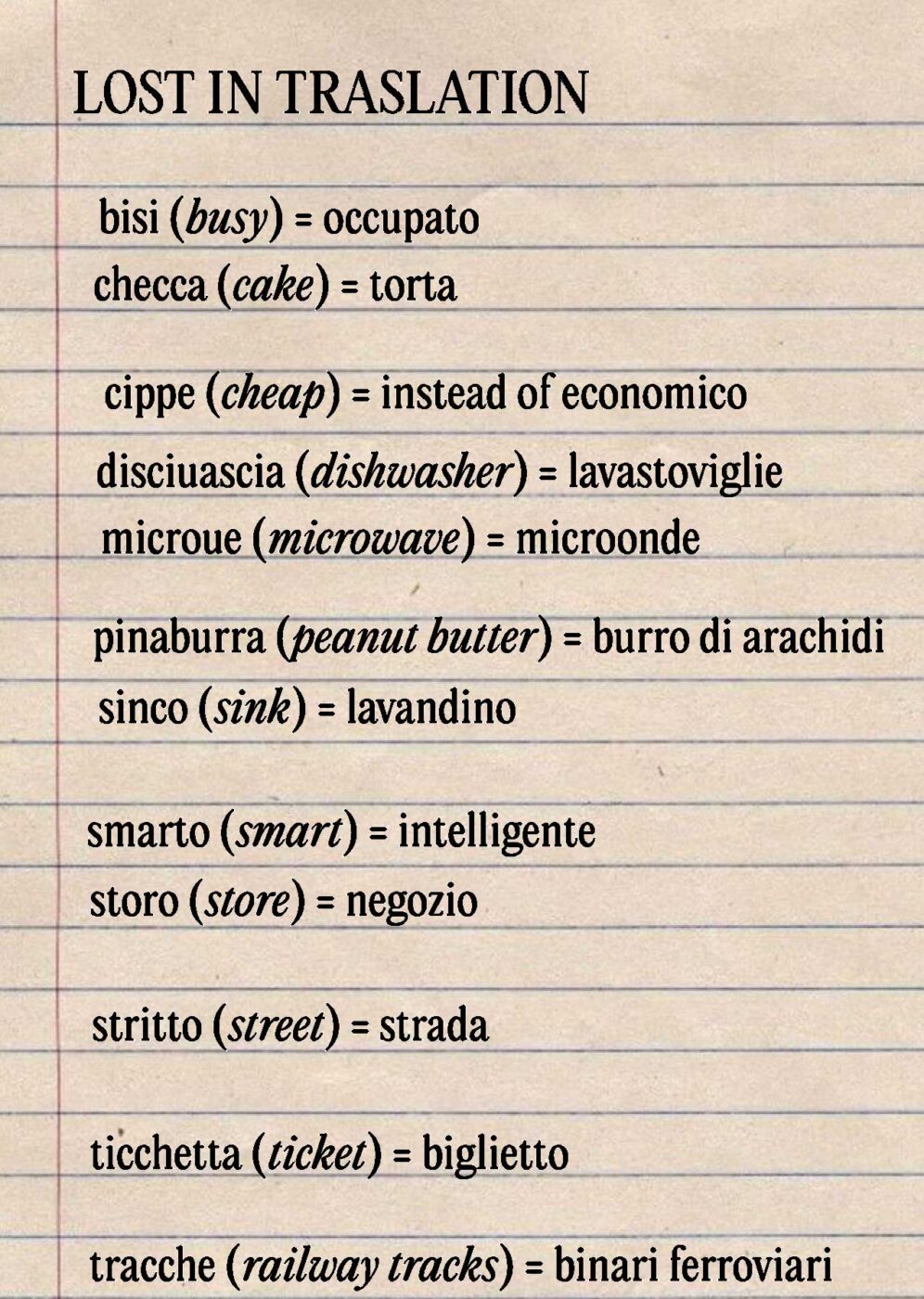

As many immigrant-born phenomena, Italiese was born out of this first generation’s desire to balance their dual identity, both Italian and Canadian, the two cultures to which they had connection. This way of speaking allowed them to integrate, but also to preserve their heritage. So, in case you end up in one of these communities, here’s a dictionary of some common words:

bisi (busy), instead of occupato

checca (cake), instead of torta

cippe (cheap), instead of economico

disciuascia (dishwasher), instead of lavastoviglie

microue (microwave), instead of microonde

pinaburra (peanut butter), instead of burro di arachidi

sinco (sink), instead of lavandino

smarto (smart), instead of intelligente

storo (store), instead of negozio

stritto (street), instead of strada

ticchetta (ticket), instead of biglietto

tracche (railway tracks), instead of binari ferroviari

Despite its widespread use, few Italian-Canadians claim to speak Italiese. Its gradual evolution leaves most (like my younger self) to believe they’re fluent in Italian. But their first encounter with standard Italian can often be earth-shattering. My mom often jokes about her experience as a child visiting relatives in Italy; the first time was a complete shock to the system, and during the beginning of her trips, she often refrained from speaking to avoid any mixups.

The future of Italiese in Canada is unknown, with many fearing its extinction. It’s why Diana Iuele-Colilli, a professor of language and literature at Laurentian University has compiled a dictionary and co-written numerous plays that use it. Her goal is to keep this linguistic phenomenon alive, even once its founders are no longer amongst us.

Young Italian-Canadians are more eager than ever to connect with their heritage, and the internet has eliminated the distance that once limited their ability to do so. Many young Italian-Canadians (myself included) have learned standard Italian, but Italiese will always hold a special place in our hearts. Standing in the boarding line of flights bound for Italy, one can hear both young and old chatting in Italiese; the comedy of visiting Italians’ reactions is priceless–apart from the odd eye roll, most demonstrate a curiosity about how this linguistic hybridization came to life.

But regardless of what happens to Italiese, one thing is certain: I’ll still catch myself asking for a slice of checca instead of torta when I’m around my family!