Bag in hand, packed with what valuables you have, you shuffle along with others boarding a ship alongside crates of citrus and sacks of coffee beans and sugar. As the ship pushes out of port, you squeeze your way through the masses waving goodbye, grasping to the bannister and leaning over to take one last glimpse at a Palermo slowly slipping away. The next weeks’ views will be endless shades of blue as you pass through the Mediterranean, Atlantic, Straits of Florida, and the Gulf of Mexico, a seascape finally broken by the narrow passing of the Mississippi River before arriving in New Orleans, unloading into the unique unknown.

Your portage is the story of nearly 40,000 Sicilian migrants during the 1800s to 1900s. Fleeing a corrupt political landscape and economic instability, Palermitani followed the shipping route of their island’s prized produce, the citrus, to a new city in the New World: New Orleans.

There’s a lot to be said about New Orleans: the city holds a rich, deep history steeped in multicultural migrations and celebrations, has faced tough times like Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and triumphs like winning the Superbowl just five years later, worships Western religion and West African spiritual folkways alike, and boasts luscious natural beauty while facing increasing threats of going underwater. In a place that swings from one end of the spectrum to the other, it shouldn’t come as a surprise, then, that there’s a slice of Sicily that helped build this city’s culture and identity as we know it today.

In a very direct sense, Sicilians found their niche importing olives, citrus, and other Italian goods, providing imported products and a labor force that helped their presence become quickly and firmly established. They dominated the oyster industry, a New Orleans staple and an all-too-familiar trade for the southern seafaring Sicilians. For them, as with many other Italian diasporas, their arrival into the New Orleans community was solidified through cuisine.

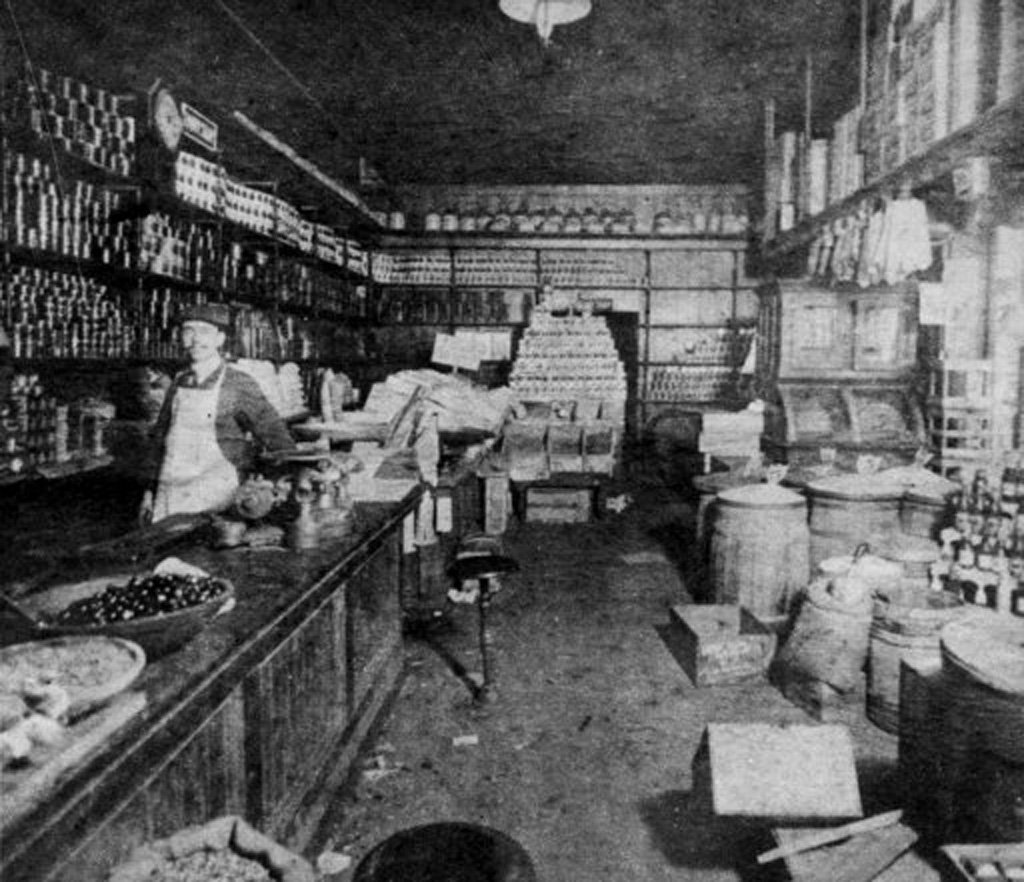

Central Grocery, New Orleans, interior view, 1906. Shopkeeper Salvatore Lupo seen behind the counter; he is credited with inventing the muffuletta (sandwich) here this year.

Opening corner shops, small restaurants, and cafes, Sicilians began to occupy physical food spaces as the working class grew; so much so that for a while, a section of the now “French Quarter” was called “Little Italy” and “Little Palermo”. A 1906 staple that still remains here is Central Grocery and Deli, established by Italian immigrant Salvatore Lupo, and home of the original muffuletta.

This skyscraper of a sandwich is not of pure Italian origin nor of pure American origin, but a prime example of Creole-Italian cuisine. The name “muffuletta” comes from street vendors slinging freshly-baked “muffuletto” bread, a Sicilian peasant bread, brought by Italians to New Orleans. When Mr. Lupo saw his patrons piling on their recently-purchased cold cuts, cheese, and spreads from his grocery onto this “muffuletto” bread, he did them a favor and decided to make it for them. Made on large rounds of this sesame seed-topped bread and layered with marinated olive salad, salami, ham, mortadella, provolone, and Swiss cheese, the muffuletta was a surefire appetite satisfier for Sicilian farmers, laborers, fruit vendors, and importers on lunch break (and has remained a staple of New Orleans’s regional cuisine today).

Danny Barker, banjo; Gregg Staffort, trumpet; Frank Naundorf, trombone. Louis Armstrong Classic Jazz Festival at Woldenberg Park, New Orleans, September 1990; Courtesy of By Infrogmation of New Orleans

Patrons and frequenters of spaces like Central Grocery and Deli were not just Italian, however. Other migrant communities coming from West Africa and the Caribbean, French and German, Native American, English, and Spanish all influenced the concept of “creole” in New Orleans, contributing to this intercultural and international landscape today, as evidenced through music, cuisine, and festivities. As with many migrant communities at the time, a sense of conviviality was born from their marginalization from a predominantly upper-class, wealthy demographic: many Black jazz musicians were welcomed into Italian restaurants and bars to play music, providing a platform for creativity in a city with a troubled (and often delayed) history with diversity. In turn, Sicilians incorporated their folk music from back home into this scene, migrants playing off of migrants, creating a wobbly-warbly, hip-hoppity jazz genre that would influence the likes of Nick LaRocca and Louis Prima, music that still spills out of restaurants, bars, and clubs today.

Italian influence was brought out of the realm of the working class into refined, mainstream scenes in around 1908, when a Mardi Gras banquet ball–usually reserved exclusively for the upper echelon of New Orleans elite–served spaghetti with red “gravy” to the attendees. Soon thereafter, dishes that reflected this multiculturalism and inter-class mingling began to appear on restaurant, hotel, bar, and club menus. Offerings like oyster and artichoke soup, chicken parmesan and cacciatore (heavy on the garlic for the Americans), Bordelaise spaghetti, and creole crawfish cream sauce could be found alongside po’ boys, jambalaya, gumbo, and red beans and rice.

Mardi Gras Rex, New Orleans, 6 March 1973; Photo by Barbara Spengler

Italian influence was not limited to food, however: there was, of course, the church. A long-standing Sicilian tradition that has become ingrained in New Orleans celebrations is that of bringing food to the altar on St. Joseph’s Day. Ornate bread sculptures of various shapes like crosses and fish (and even alligators!) pay homage to the saint’s woodworking profession, while piles of confections like the fig-filled cucidati, sticky and sprinkled pignolata, and the fried goodness of zeppole are spread throughout citrus and fava bean offerings, a reminder of the legume that broke the Medieval-era famine of Sicily. The day is celebrated with–you guessed it–even more food, as a big community feast for dinner is offered to any and all, usually in the form of a giant pasta.

Of course, as it happens in New Orleans, this holiday has become “creolized”: historically Black-led and integrated churches now also celebrate St. Joseph’s Day with altar offerings–a lasting token of some of the first relationships Sicilians made in the city–and the holiday has made its way into the most well-known celebration on the Mississippi, Mardi Gras. Italian, Black, and Irish krewes (essentially an organization or association that stages a parade or other event for Mardi Gras) all pay homage to the saint around his feast day, donning outfits spanning from hand-sewn elaborate regalia to formal tuxedos and ball gowns. As with many celebrations, alcohol flowed–wine from the Italians, rum and distilled liquors from the Black community, whiskey from the Irish. Instead of candies, beads and fava beans are thrown–signs of prosperity and wealth. The third weekend in March hosts St. Joseph’s Day and Super Sunday, the largest Mardi Gras celebration day for the Mardi Gras Indians. This yearly moment in time is truly a unique celebration of the pre-Easter festivities and the biggest days of the year for the New Orleans community.

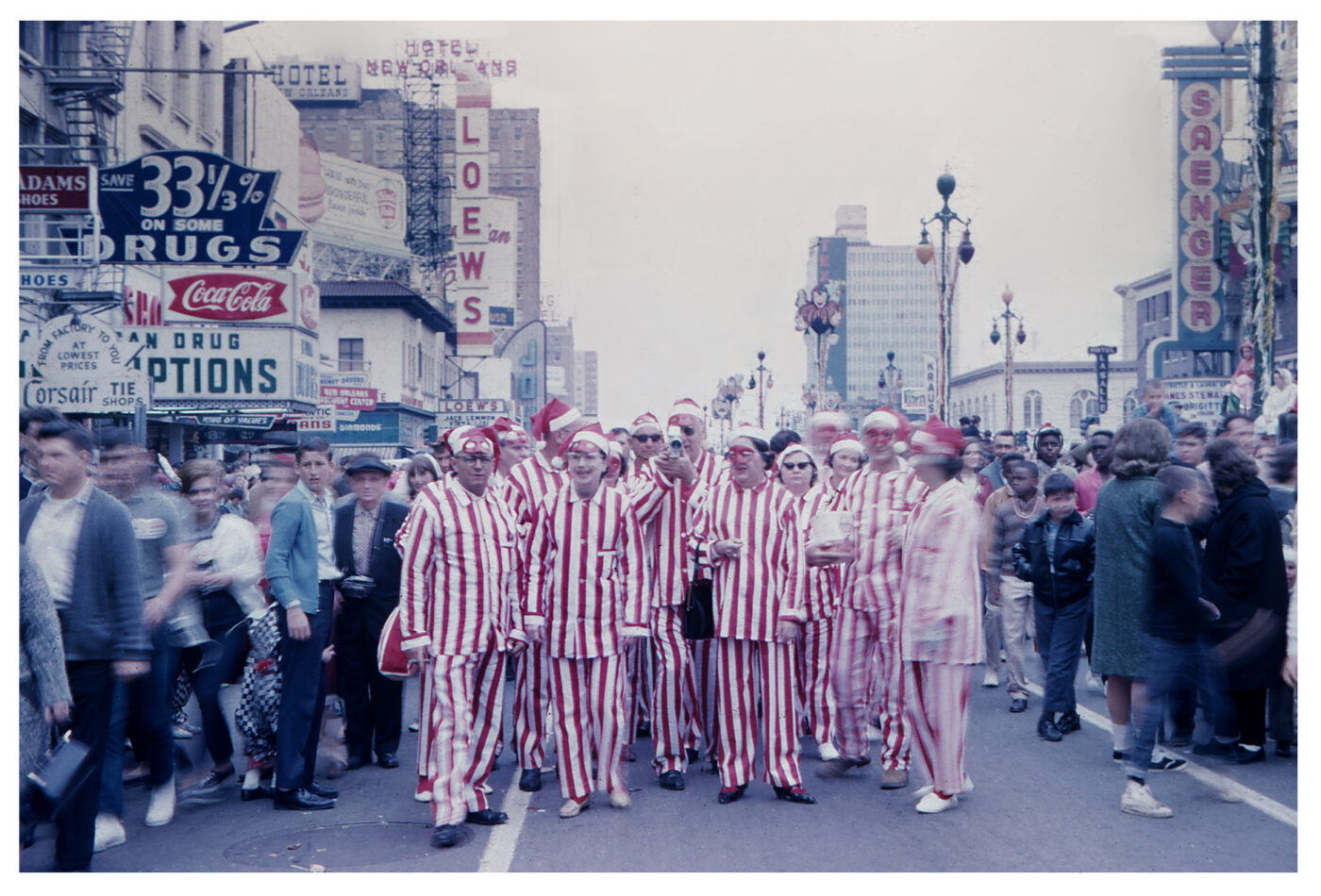

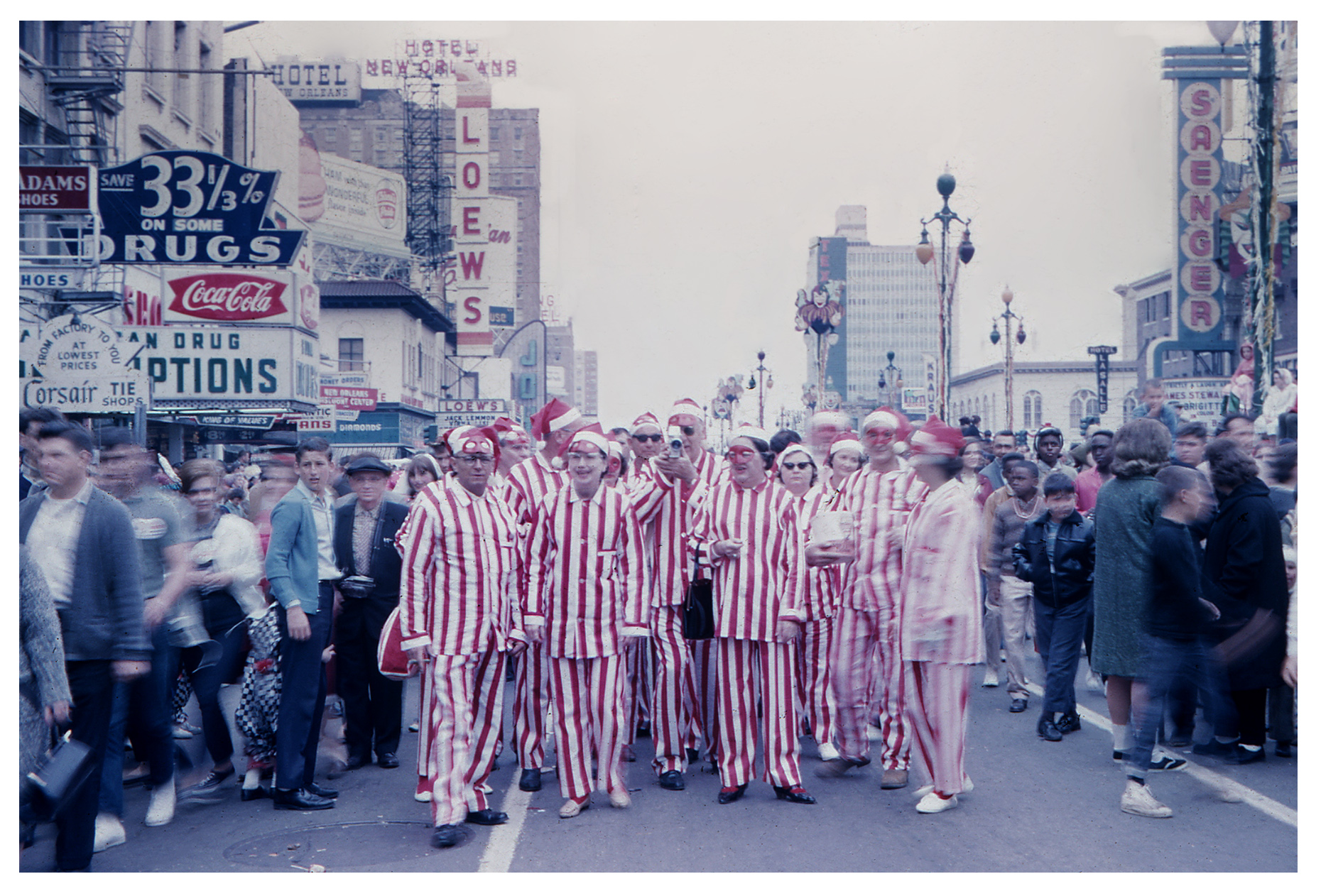

New Orleans 1965 Mardi Gras Costumers on Canal Street Kodachrome; Photo by Tom Hart

The list of Italianicity–both celebratory and damaging–in New Orleans goes on: ragtime jazz; the founding of Progresso Foods, an American household brand; the 1981 lynching of 11 Italian-Americans after being acquitted from the murder trial of a police chief, their victimhood resulting in the country’s largest mass lynching to date; contributors to the city’s architectural churches; conviviality of Sicilians and Creole in the General Strike of 1892; contributing old-world traditions of parades and public displays of mourning to New Orleans-style funerals; the first use of the word “mafia” in print; red “gravy” and char-broiled oysters; and the iconic New Orleans accent. This list seeks to highlight that, like any community and culture that migrated to the United States, Sicilians faced some of the same triumphs and let-downs, making space both for their continued Italian culture and integration into the American way.

Perhaps it is the love of tradition, perhaps the acceptance between migrants, or perhaps the never-boring, ever-surprising, hybridized celebratory lifestyle that is born of New Orleans–whatever it can be distilled to or defined by, it shouldn’t be. It seems just right that Sicilians found a home in a place just as unique, wild, and complicated as their old one back in Italy.