When thinking about Venice, many adjectives might come to mind: romantic, historic, picturesque, timeless. But sustainable? Perhaps not. It’s difficult to think of Venice as a sustainable place. In fact, at first glance, it seems quite the opposite: a city built on a forest of timber poles driven into the mud of a lagoon; a utopia sustained by sheer optimism, ingenuity and, as the UNESCO World Heritage listing puts it, “the victorious struggle against the elements.” And if this ongoing tension between human endeavor and nature has proven successful for the past 16 centuries, today the focus appears to lie increasingly on the struggle itself. Rising water levels, environmental changes to the lagoon’s ecosystem, and increasingly frequent and devastating high tides—coupled with mass tourism that strains the city’s urban and social fabric—are steadily eroding Venice’s ability to persevere.

“If we looked at it from a financial standpoint alone, we should just let it sink,” a friend of mine working in business and economics once jokingly remarked. But of course, that is not an option. Which is why, for decades now, Venice has been at the center of attention and action across research, literature, journalism, and private initiatives all focused on how the city can not only survive, but thrive, amid today’s dire circumstances. The goal is to position Venice not merely as a place in need of saving, but as a hotspot for change and adaptation—one where the challenges we see clearly are, on some scale and in various forms, occurring across the globe.

Salvatore Settis has a point when, in his book, If Venice Dies, he describes Venice as a thinking machine—a universal toolbox of concepts through which we can reflect on the very idea of the city. Venice, he writes, is a machine for contemplating the nature of urban life and the practices of citizenship—life in the city as historical sedimentation, as lived experience in the present, and as a blueprint for a possible future. To look at Venice and think only of Venice, he argues, is misleading: the processes unfolding there—particularly the degradation and depopulation of the historic city, the rhetoric of a standardized modernity, and the fixation on profit—mirror those happening in many other parts of the world. Which is why, conversely, it may be insightful to examine them up-close and with some examples to see what can also be applied across the board.

Among the most optimistic endeavors to reframe Venice as a model is the Venice World Sustainability Capital Foundation. Operating under the claim “the oldest city of the future,” it aims to make Venice “a benchmark for urban quality of life—an example that can inspire other national and international contexts” through the creation of an integrated model working towards a sustainable future for the city and its surrounding territory. “Thanks to its small size and its territorial peculiarities, Venice is an ideal laboratory to generate, develop and test a new model of urban sustainability—social, economic and environmental—as a happy synthesis between past resilience and future prosperity,” states the Foundation’s website.

Yet the Foundation has often been accused of being little more than a greenwashing exercise—a hypocritical, smoke-and-mirrors endeavor lacking a concrete action plan and a detailed financial framework, all while counting prominent politicians and oil and gas companies among its stakeholders. It is true that Venice still ranks among the top Italian cities for air and water pollution, due to a range of factors including inadequate sewage infrastructure, polluting public transport, and the elephant in the room: the heavy industrial presence of the Porto Marghera conglomerate. Not to mention the issue of short lets and tourism management.

As local administrators introduce controversial measures—such as the entrance fee during the high season—while falling short on residents’ demands for, say, adequate housing policies and other pressing matters, it is becoming increasingly clear that meaningful, albeit small-scale, action related to sustainable change is not being driven by large institutions, but rather by grassroots initiatives and research efforts. These often bridge academic work with the active involvement of local associations and individuals working across a wide range of fields—from architecture to urbanism, environmental studies to food and hospitality, and from activism to the visual arts and literature.

Exploring the lagoon with Barena Bianca; Photo by Valeria Necchio

One such example is Vital, a project led by a group of experts focused on the maintenance and enhancement of the natural capital of the Venetian Lagoon. “The ecological heritage of the Lagoon is considered a form of natural capital that generates various forms of wealth. Vital is committed to finding ways to protect and enhance this natural capital for the benefit of current and future generations,” says Margherita Scapin, an environmental science researcher and activist with the NGO We Are Here Venice, and a member of the Vital team.

Jane da Mosto, founder of We Are Here Venice, describes the city as “a mirror on the world: a source of inspiration and a microcosm of many of the most important global challenges.” Through the organization, she promotes strategic and participatory approaches to safeguarding both the city and its lagoon, advocating for sustainable development grounded in scientific evidence and research. Among the many campaigns launched by We Are Here Venice is #veneziaèlaguna, a communications initiative that highlights the crucial interdependence between the city and the ecosystem in which it exists. “The survival of this environment has been ensured over the centuries by planned human interventions. Because the Lagoon is the result of the encounter between the salty waters of the Adriatic and the rivers of the Veneto plain, its balance is naturally precarious—threatened, on the one hand, by the possibility of completely silting up and, on the other, by the invasion of sea water. Vital’s activities are part of a tradition of interventions aimed at restoring these optimal dynamic processes,” adds Scapin.

Indeed, recent research has identified several critical insights regarding Venice and its lagoon as focal points for climate change, revealing significant shifts in both the region’s climate and its ecosystems. Over the past three decades, the relative mean sea level in Venice has risen by approximately 4.9 mm per year, leading to more frequent and prolonged flooding events. Projections suggest that, under worst-case scenarios, sea levels could rise by as much as 3.47 meters by 2150 during extreme high tide events, potentially submerging large portions of the lagoon. Meanwhile, the Northern Adriatic has warmed by 1.8°C over the same period, outpacing the global average and surpassing the thresholds set by the Paris Agreement.

The shallow nature of the lagoon exacerbates these temperature changes, particularly in tidal flats, threatening the delicate balance of its ecosystems. As sea levels rise and temperatures increase, the lagoon’s biodiversity is at risk, with the potential for species migration, habitat disruption, and the dominance of non-native species (cue the blue crab invasion—more on that in a moment). While the MOSE flood barriers, installed in 2020, have successfully mitigated high tides, they have introduced new challenges. These barriers have reduced water exchange between the lagoon and the sea, potentially worsening marine heatwaves in summer and cold spells in winter. Furthermore, the barriers have altered sediment deposition patterns, resulting in the formation of new landforms, such as Bacan—a once transient sandy islet that has now become a permanent island. While such changes create new habitats and recreational spaces, they also highlight the complex relationship between human interventions and the natural processes of this liminal space.

Marco Bravetti of Tocia! foraging

“A still underexplored yet crucial issue for Venice and its lagoon is the recognition of nature’s rights within the lagoon ecosystem,” says Alice Ongaro Sartori, a researcher in visual culture and editorial curation with a focus on ecology and the public sphere, who also oversees social communication at wetlands, a Venice-based publishing house dedicated to social justice and environmental sustainability. “Introducing this perspective into the legal sphere wouldn’t only lead to more effective environmental protection, but would also reshape how we perceive and relate to the landscape in our everyday lives. Literature can play a part in this shift—and in fact, we at wetlands are working towards it.”

In response to the urgent and complex issues of our time, wetlands has committed to publishing texts that explore environmental, urban, social, anthropological, and cultural themes—with a special emphasis on Venice and its lagoon, while also engaging broader, transnational perspectives.

How can literature and publishing help reframe Venice’s narrative in the context of its challenges—especially as these are mirrored in other regions? “Amitav Ghosh, in The Great Derangement, points out how traditional narratives have often sidelined climate change, treating it as an exception rather than a lived, everyday condition. Publishing books that connect Venice to the climate crisis, rising sea levels, and mass tourism helps reimagine the city not as a place doomed to vanish, but as a living laboratory—actively producing knowledge and imagining alternative futures,” Ongaro Sartori explains. “A publishing house that’s attuned to these themes can amplify diverse voices—from writers and artists to activists and scientists—placing Venice in dialogue with other vulnerable cities. It allows us to understand that, although these are global problems, they can also be tackled collectively.”

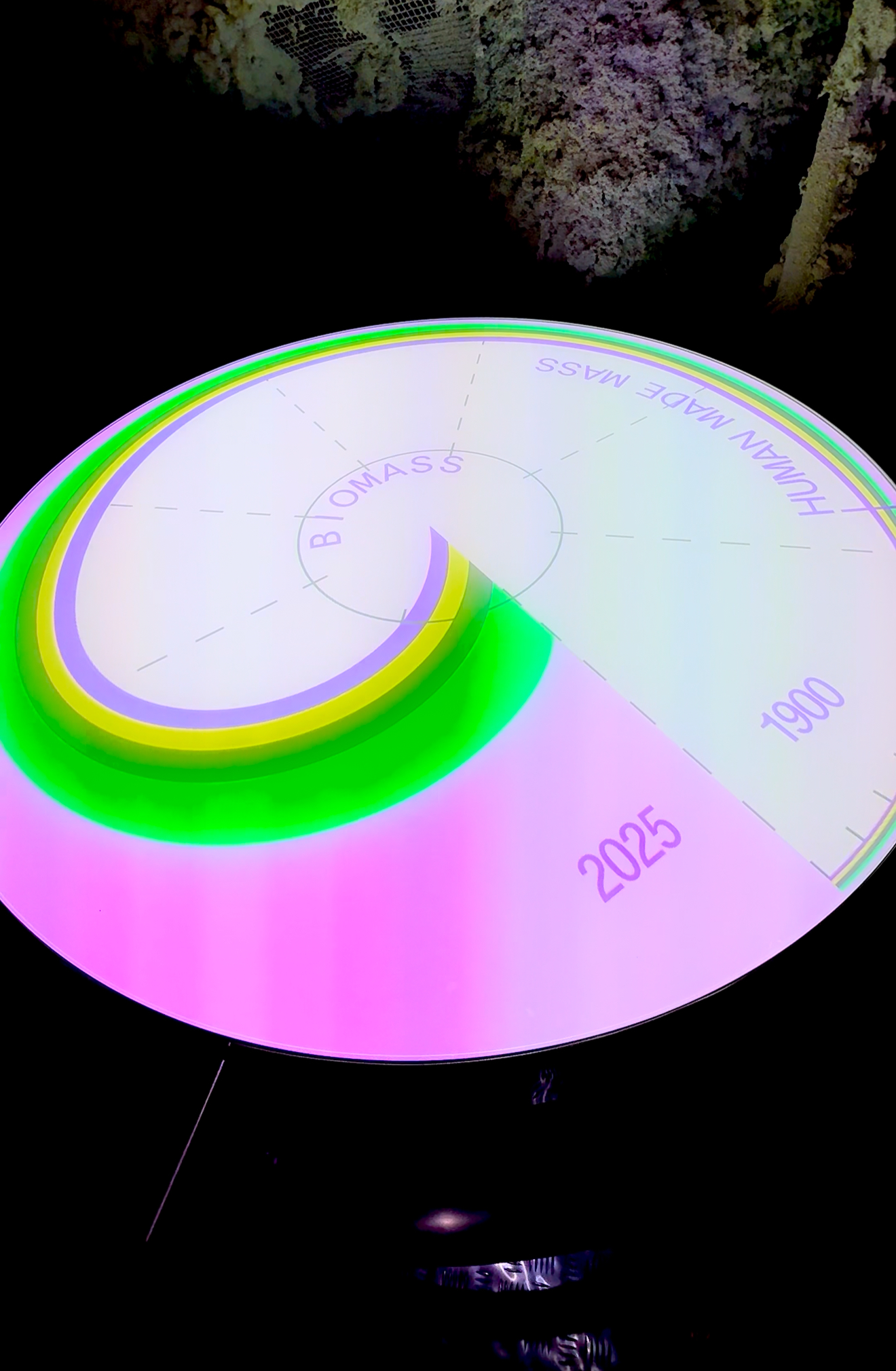

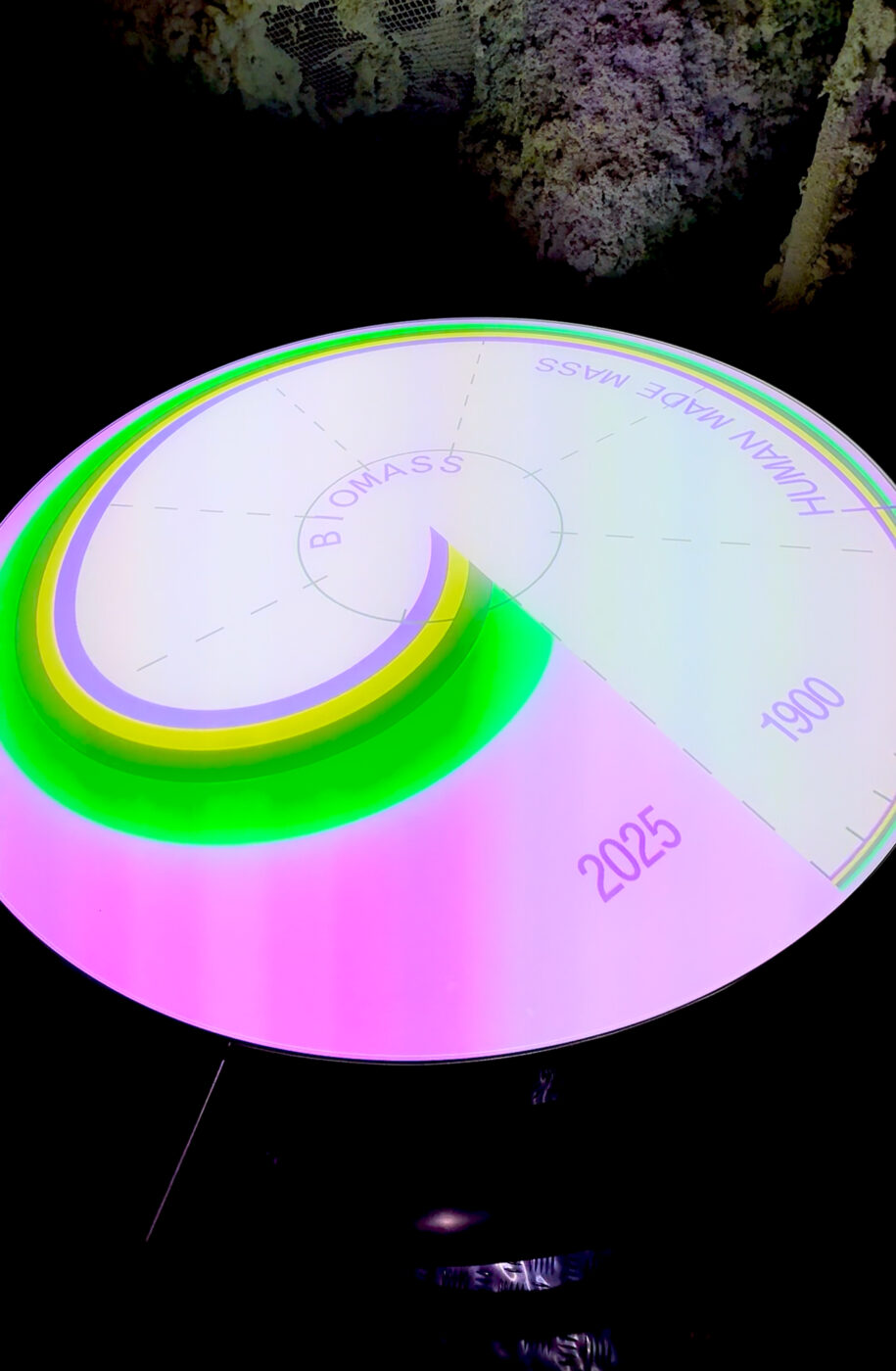

Architecture Biennale 2025; Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.

As Venice prepares for another Architecture Biennale opening on May 8th and 9th, 2025, its theme, Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective, under the curatorial guidance of Carlo Ratti, invites “different types of intelligence to work together to rethink the built environment” and to “experiment beyond today’s limited focus on AI and digital technologies.” It also asserts that, when “the systems that have long guided our understanding begin to fail, new forms of thinking are needed. For decades, architecture’s response to the climate crisis has been centered on mitigation—designing to reduce our impact on the climate. But that approach is no longer enough. The time has come for architecture to embrace adaptation: rethinking how we design for an altered world.”

And yet, it is partially due to large annual events like the Biennale that the city has become increasingly unsustainable. “As an architect and director of an open-access cultural platform, I am disheartened by how major cultural players capitalize on seasonal programming in line with the Biennale calendar—a form of extraction that exploits La Serenissima’s unique ability to attract vast numbers of people,” says Federica Sofia Zambeletti, founder and managing director of KoozArch, a research studio and platform for critical architectural discourse. Through a magazine as well as exhibitions and events, KoozArch embraces a multigenerational and multidisciplinary approach, challenging the historically and measurably extractive nature of architecture in favor of a more regenerative and accessible form of practice. “This capitalisation results in thousands of square meters of space (from apartments to entire historic buildings, even islands) lying dormant and inaccessible for six months a year. In this regard, a different and more sustainable form of inhabitation—at least from a cultural perspective—would be to conceive of sustainable, year-long programming. This could consider how such spaces may be mobilized to respond to the necessities of Venetians, a rare breed of resilient people who—despite the hardships—continue to inhabit and tend the lagoon with pride.”

When looking at what could be done in terms of regenerative architecture in the lagoon, Zambeletti states: “Once again, I think it’s a matter of reclaiming spaces for collectivity and regrounding the often-flattened notion of regeneration as a truly social practice. Thankfully, there are a number of initiatives working in this direction: the recently established co-working space, Versatile and the more historic cultural BoccioFila are great examples of spaces claimed and safeguarded for the needs of the local citizens. At an infrastructural scale, the work of OCIO Venezia in collecting, analyzing, and monitoring the housing situation in Venice is pivotal in understanding how the city is changing and what actions need to be taken to counter the most evident critical issues. Of course, there is a lot of strength in projects which activate underused or abandoned spaces, nurturing collaborations between local and global actors; for instance, the Cinema Galleggiante or the ambitious project for the Isola di Sant Andrea, both under the guidance of Paolo Rosso.”

The lagoon in the Biennale off-season; Photo by Valeria Necchio

A similarly community-driven, multidisciplinary approach can be seen in the work of Amina Chouaïri, a PhD student in Urbanism at IUAV researching the ecological restoration of the barene (marshlands) in the lagoon through the lens of landscape architecture as a way to reveal its inconsistencies. “I believe the present moment of the lagoon is the most important, yet also the most overlooked. A great deal of attention is given to heritage and the nostalgia for what once was—the decline we have been experiencing for two centuries—while, on the other hand, there is a strong focus on the future, particularly looking ahead to 2050. But although this has implications for the present, the present itself remains largely absent from critical discourse.”

In this sense, as both a researcher and a resident of Venice, she felt compelled to dedicate time to the current state of the lagoon by being physically present in it. “I felt the need to be outside, immersed in the environment, because as I continued my studies, I realized this aspect was somewhat lacking.” She immediately noticed that this strong desire to experience the landscape on a 1:1 scale was widely shared. In response, she began organizing outings—both formal (in partnership, for example, with institutions such as Ocean Space and TBA21, or in collaboration with the environmental and educational association Barena Bianca) and informal—taking time to explore the lagoon with friends and offering moments of enjoyment with a reflective twist.

“One such outing led to the idea for a photography project with Matteo De Mayda, while another inspired the Convivio Acquatico (a culinary symposium) with the “convivial collective” Tocia!, led by chef Marco Bravetti, and videomaker Matteo Stocco. I like the idea of organizing and doing something tangible, bringing together different realities. All of this is part of a shared will to create connections within the landscape and the place itself.”

“I would say that over the past 50 years, since the major environmental movements of the 20th century, ecological awareness and efforts to conserve and protect the lagoon have grown tremendously,” says Chouaïri. “Today, these issues are carried forward—sometimes in a fragmented way, at other times more cohesively—by the remaining environmental associations. At the same time, I recognize the internal challenges within activism in Venice. It is widespread, and as a result, conflicts occasionally arise, creating a mosaic-like fragmentation, even though the ultimate goals remain aligned.”

Amina Chouaïri in the field; Photo by Matteo De Mayda

I myself joined one of the boat excursions organized by Chouaïri and Fabio Cavallari of Barena Bianca across the northern lagoon. The purpose of the expedition was to explore alternative food habits and the concept of culinary resistance in relation to this uniquely amphibious and liminal environment.

During the first part of the morning, a few speakers read poignant passages from books about the islands of Venice, particularly from Paolo Barbaro’s Ultime Isole. This was followed by a discussion centered on why, in our current era—when climate change presents such urgent challenges—it is vital to shift our perspective on the natural world. Rather than asking what these marshes and wetlands can do for us, we should consider how we might adapt to live in harmony with them. Is it possible? Can we learn to observe nature without seeking to tame it? Can this happen here, in a place that is so often seen as in need of saving? Even the MOSE flood barrier system, one speaker pointed out, is an imperfect, temporary, and much-criticized intervention—yet in many ways, it continues the long-standing tradition of Venice’s attempts to manage its unstable environment. It was agreed that, to establish a genuine dialogue with this ever-changing and fragile landscape—fragile in the sense of being unstable—we must begin to live in closer symbiosis with our surroundings, asking better questions and seeking better answers.

The conversation soon turned to food and, later in the day, continued along this thread during a visit to I Sapori di Sant’Erasmo, a family-run farm on the island by the same name. There, Fiorella “Cosetta” Enzo, the owner, generously shared her wealth of empirical and technical knowledge as we sat beneath her shady pergola, fatigued by the relentless sun on what was the first hot day in weeks. We spoke about water management and the local effects of climate change, which seem to be taking on an increasingly tropical character—longer rainy seasons and extended droughts that are placing native plants under considerable strain. A participant asked about the artichoke—particularly the prized, tulip-shaped variety called carciofo violetto (violet artichoke), so emblematic of Sant’Erasmo. What made it so special, they wondered? “It’s not the plant that’s unique,” Cosetta replied. “Anyone could take this variety and try to grow it elsewhere. But only here have these plants found this soil, with its perfect balance of clay and salt.”

She spoke of building a community of growers who could support one another and act as stewards of the land. Offers to buy her land arrived almost daily, Cosetta said, but she remained firm on her decision to stay; that place was her whole life. Yet she acknowledged that the island’s future remained uncertain, heavily dependent on the intentions of the heirs of the current, ageing generation of growers. With few exceptions, many were likely to sell to the highest bidder—most likely a foreign developer—and simply move on, thus undermining the natural vocation of an island—Sant’Erasmo—that, for centuries, has acted as “the garden of Venice”, being not just the largest within the lagoon but also one of the most fertile.

Carciofo violetto; Photo by Valeria Necchio

Not far from Cosetta’s farm lies another agricultural initiative, Osti in Orto, a collaborative project launched in late 2020 by 13 Venetian restaurateurs, led by Cesare Benelli of Al Covo. Aiming to bypass traditional supply chains and reconnect with the local territory, the initiative cultivates vegetables specifically for use in the participating restaurants’ kitchens, thereby revitalizing local farmland and offering a wide range of flavor-rich vegetable dishes to the restaurant’s patrons. The four-hectare plot is managed by Mario Saviolo, a local with a background in environmental biotechnology, and follows traditional practices such as planting in harmony with the lunar cycles. Osti in Orto also offers an immersive experience, inviting visitors to explore the gardens with a guide and sample the freshly harvested produce, simply prepared into seasonal snacks.

Though perhaps the prime example of field-to-table cuisine in the lagoon can be found at Venissa. Under the guidance of Chiara Pavan and Francesco Brutto, the Green Michelin-starred restaurant offers a snapshot of the lagoon’s environment—specifically that of Mazzorbo Island and the estate’s gardens—translated into verdant, thought-provoking, predominantly plant-based dishes. Animal protein is used sparingly and often comes from invasive aquatic species that have proliferated in the lagoon. By inviting diners to act as symbolic predators of these non-native species, and presenting them in unexpectedly delightful and inventive ways, Pavan and Brutto are reshaping the perception of contemporary Venetian cuisine.

They were among the first in the area, for instance, to serve the invasive and voracious blue crab. One of the fishermen supplying their restaurant began bringing them in by the bucketful, having found them entangled in nets intended for the smaller green crabs—moeche. Pavan and Brutto started purchasing blue crab and featuring it on the menu, and following this initial experiment, extended the approach to other non-native bivalves and fish. They also observed that the estate was increasingly populated by halophytes—salt-tolerant herbs and plants such as samphire and sea purslane—due to rising salinity levels in the island’s soil. These, too, became integral to their experiments in “environmental cuisine”, lending a naturally saline crunch to their dishes—like their raviolo with fish sauce, minced sea fennel, raisins, and halophytic herbs, to name just one.

The invasive blue crab; Photo by Valeria Necchio

Halophytes are central to many contemporary projects and a growing focus of chefs working with terroir-driven cuisine. Perhaps the most notable initiative is led by the research agency The Tidal Garden, which since 2020 has explored the edible potential of halophytes as a tool for cultural adaptation to climate change. Promoted by prometheus_open food in collaboration with local farmers in the Cavallino-Treporti area of the northern lagoon, the project seeks to develop a communal adaptation strategy for the region’s increasingly brackish soils and in the face of climate change. Many halophyte species are endemic to the lagoon and historically contributed to the—glass manufacturing, more than culinary—prosperity of Venice and surrounding towns before fading from local culture. Now thriving in saltmarshes and expanding farmlands, these salt-tolerant plants offer the potential to redefine farming and eating practices in the Venetian Lagoon under new tidal conditions.

The culinary realm offers abundant opportunities for cross-pollination, serving as one of the most tangible ways to experience and reflect on the changes the lagoon is undergoing. Community events organized by the very same Tocia! or The Tidal Garden often weave together conversation, contemplation, and sensorial engagement—as it happened on the occasion of the Convivial Tables series by TBA21–Academy, which framed the dining table as “the perfect avenue to discuss the complex ties between what we eat and its ecological impact, with a particular focus on its effect on bodies of water.”

When it comes to Venice and sustainability, then, no stone seems to be left unturned, no field unexplored. At the crossroads of ecology, cuisine, art, literature, activism, urbanism, and architecture, the conversation is alive, ongoing, critical, and thought-provoking—not quite to the point of asking, “Shall we let it sink?” as my friend joked—rather, constantly raising questions about how to shape the future of the city and its lagoon in a way that feels less like a struggle and more like a confluence of intents.

Experiments with halophytes at the Tidal Garden; Photo by Camilla Glorioso