Pasta, pasta, pasta is all that seems to be on anyone’s mind when perusing the primi section of an Italian menu, but look to the very bottom of the list and you’ll find a plate, placed there almost cursorily, with an underdog story: the creamy, wheat-free risotto.

Rice is now the most consumed cereal in the world, where it is steamed, boiled, made as pilaf or paella, stuffed inside vegetables, and paired with about anything you can imagine, from vegetables and eggs to raw fish and meat. Except in Italy. Here, you’ll find it in just a few dishes: supplì in Rome or arancini in Sicily, mixed with potatoes and mussels in Puglia, as sartù di riso in Campania. The only preparation you may find from North to South is risotto.

This creamy, hearty dish comes from Northern Italy, but it’s quite a recent introduction to the culinary canon. One of the now-most iconic plates of Italian cuisine, risotto doesn’t have the same centuries-old traditions as Italy’s other dishes–it certainly wasn’t eaten by the ancient Romans–even though rice has been in the country for nearly a millennium. Risotto has only risen to fame and spread around the boot over the last 15 years, in an equal–yet opposite–journey to pizza and pasta.

RICE TO RICHES

Like many of Italy’s famed ingredients–wheat, citrus, tomatoes–rice is not native to the Mediterranean. Wild rice was gradually domesticated in India and Southern China–regions with monsoons and heavy rains–some 5,000 years ago, millennia before it reached the Mediterranean. In the 14th century, the Arabs brought rice to Sicily and Spain, where cultivation began in the Kingdom of Naples and gradually spread upward. The first rice paddy was inaugurated in 1468 in Florence, while the first documented evidence of rice cultivation in Italy dates back to 1475 in Lombardy. From there, it spread north to the marshy areas of Piedmont’s Po Valley–now famous for the Carnaroli and Arborio rice varieties–extending into the 19th century to cover over 250,000 hectares. Today, the country is Europe’s largest rice producer, but the Italians still favor wheat.

Foreigners to this cereal, Italians first cooked rice in the only way they knew how to prepare a grain: boiling it. What resulted was a muddy, overcooked, flavorless, and uninviting dish, much different than the fluffy pilaf of the Middle East, the rich paella of neighboring Spain, and the risotto we know today. Recipe books from the 18th century recorded just this one cooking technique: boil the rice in cold water–sometimes even soaking it beforehand–until it resembles more of a soup or polenta. These cookbooks, along with other written and verbal accounts from the 16th century, point to this dish’s prominence (only) in Milan and Northern Italy.

This is less due to taste preferences and more due to the natural predisposition of the land: polenta and rice were grown and eaten in the North, while wheat was grown and dry pasta was eaten in the South. The nickname given to the Neapolitans, “mangiamaccheroni” (macaroni eaters), competed with the term “polentoni” for the people of the North. Otherwise, in the South, rice was only occasionally eaten in Lazio, Sicily, Puliga, and Campania. Pasta moved its way northward pretty quickly, but it wasn’t until the invention of risotto that rice found a solid following south of Milan.

Courtesy of Giacomo Milano

THE INVENTION OF RISOTTO

In 1779, Antonio Nebbia’s book Il Cuoco Maceratese contains the first record of a non-boiled rice recipe, calling for the grain to be soaked thoroughly, sautéed with butter, then moistened with broth. Then, in 1809, we find “yellow rice in a pan”–rice sautéed in butter and mixed with sausage, onions, and saffron–in Milanese city chronicles. These golden threads were introduced to Milan in 1535 with the beginning of Spanish rule, although the combination of rice and saffron dates back to the Middle Ages in other countries. Legend has it that the first Italian pairing of rice with saffron–the predecessor to risotto alla milanese–originated in 1574 when Valerio della Fiandra, a painter working on the Duomo, decided to add the saffron to the rice at his daughter’s wedding, a joke to surprise her soon-to-be husband, a colleague nicknamed Zafferano for his love of yellow paint.

But it’s not until 1891 that we got the first official “risotto” recipe: in his famed La Scienza in Cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene, Pellegrino Artusi, the father of Italian regional cuisine, provided 12 recipes for risotto. He includes three variations of the Milanese style: rice, butter, onion, saffron, along with a “reinforced” version with Marsala or beef marrow, Parmesan, and a dash of white wine–”heavier on the stomach but more flavorful,” according to the author. Then, in the 20th century, recipes became numerous with countless variations, including one from Petronilla–whose cookbook of economical recipes was a bible during the Fascist Era–that includes onion fried until it turns black.

RISOTTO’S RISE TO FAME

Unlike polenta, which still finds itself relatively doomed to its cucina povera identity, risotto has brightly emerged into the contemporary cuisine of Italy at the hands of some creative Northern Italian chefs. In risotto’s birthplace, Milan, chef Gualtiero Marchesi–known as the father of contemporary Italian cuisine–reinvented the dish in 1981 with his “Riso, Oro e Zafferano” (rice, gold, and saffron). In his take on risotto alla milanese, he placed a square gold leaf on top of the rice, changing perceptions of the dish from something simple to something with high value. His disciple Davide Oldani, a two-Michelin-starred chef, created the dish “Zafferano e Riso alla Milanese” for Expo 2015 in Milan; Oldani didn’t mix the saffron into the risotto, but spiraled a separate yellow sauce–made of salt, water, and saffron–onto the simple, white-colored rice, a design now mimicked on dozens of risottos in Italy and around the world.

Riso, Oro e Zafferano by Gualtiero Marchesi - Courtesy of Gualtiero Marchesi Foundation

Among the most famous (and similarly copied) risottos in Italy, there is also the “Risotto allo zafferano con polvere di liquirizia” (saffron risotto with licorice powder) by the three-Michelin-starred Chef Massimiliano Alajmo of Le Calandre in Rubano, Padova and the sweet, spicy, and shockingly pink “Risotto alle Rape Rosse e Salsa al Gorgonzola” (risotto with red turnips and gorgonzola sauce) by Chef Enrico Bartolini. Among the rice fields of Vercelli in Northern Piedmont, the Costardi brothers serve at least twenty different kinds of risotto–including a take on carbonara–in their self-titled restaurant; each is served in a can, in a reference to Worhol’s painting.

RISOTTO TRAVELS SOUTH

Over the last decade or so, risotto has spread like wildfire to the kitchens of Southern Italian chefs. Here, they’ve adopted the northern dish by adapting it to fit their local ingredients, which most often includes seafood. The first southern risotto to make headlines was that of Gennaro Esposito about 20 years ago: “Risotto al Pomodoro Cuore di Bue con Limone Candito, Calamaretti e Provola” (risotto with beefsteak tomato, candied lemon, small squid, and provola cheese). Similarly, iconic Campanian restaurant Don Alfonso 1890 has seen the evolution (and obsession) of their “Risotto al Profumo di Cedro, Scampi, Alghe, Ricci di Mare e Caviale” (risotto with citron, shrimp, seaweed, sea urchins, and caviar).

RISOTTO TODAY

Fine dining restaurants in Italy, and even internationally, continue to experiment with risotto. Most of this gastronomic research involves temperatures and creaming techniques. At Lido 84 in Garda–one of The World’s 50 Best Restaurants–Chef Riccardo Camanini dyes his risotto black with squid ink and serves it lukewarm, dripped messily onto a plate to resemble a Jackson Pollock painting. On one hand, the classic risotto alla milanese reigns uncontested, but on the other, chefs are trying vegetable oils, cocoa butter, and coconut butter as alternatives to butter and cheese, or even, in the case of three-Michelin-starred chef Niko Romito, with nothing. In 2023, he introduced a risotto onto his vegetarian menu that is made with no fats, still creamed perfectly, and served cold. (How he does so has not been revealed!)

Riccardo Camanini black risotto with squid - Courtesy of Lido 84

THE 101

Since the rice itself is flavorless, the real limit to cooking risotto is your imagination. Even the color can vary: bright yellow with saffron, white if left simple, green with pesto, dark brown with red wine or meat reductions, black with squid ink. Pair the rice with mushrooms, peas, pecorino, sausage, pumpkin, asparagus, or seafood. Risotto is topped with sea scallops in France’s Côte d’Azur, with osso bucco in Milan, and with shaved truffles in Alba and Tuscany. Trends come and go, like adding strawberries to risotto–a recipe born (and that rightfully died) in the 1980s–or chicken, which is popular in Italian-American cuisine, yet something no Italian would touch.

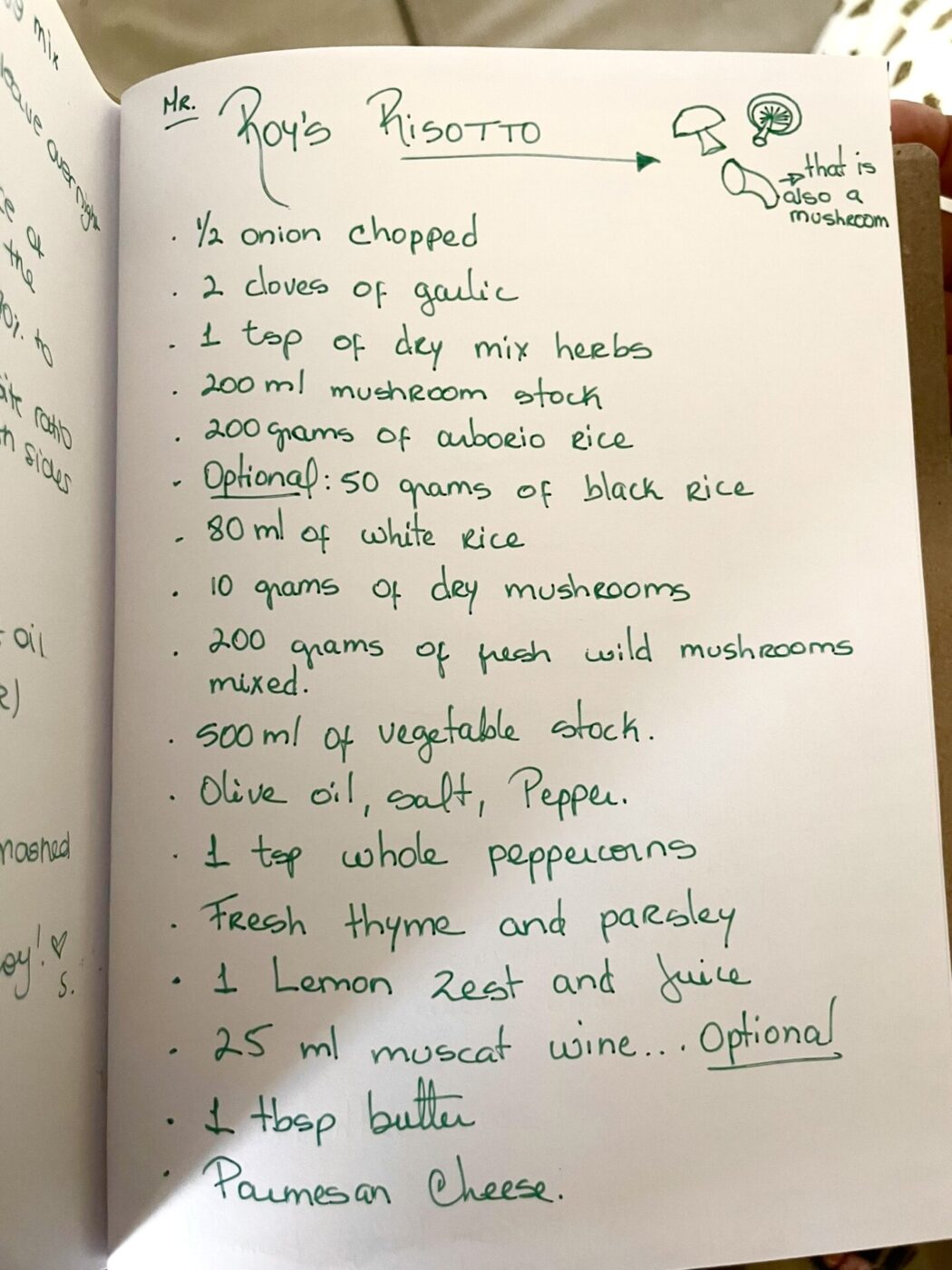

Broth, yes; broth, no. Stirring it, yes; stirring it, no. Wine, yes; wine, no. Carnaroli or Arborio. The schools of thought on risotto are many, with preferred preparations changing by the era, region, and chef. Yet, every risotto follows this basic format: saute onions in butter until translucent. Add the rice–preferably carnaroli–and stir, toasting for about 1-2 minutes. Add white wine and stir until absorbed. Add (warm!) broth–usually vegetable or chicken–little by little, stirring constantly until it is nearly absorbed between additions. Then shut it off, add in cold butter and Parmesan, and stir. It should be creamed skillfully, either by using a wooden spoon or by tossing it in the pan to form those famous waves. The goal is to make it creamy, almost fluid, and shiny, with the grains well integrated and slightly al dente. The most important thing is to have a just-done-at-the-moment risotto: it takes at least 20 minutes of patient stirring, so beware of restaurants that bring the primo out in just five minutes; it means the risotto’s pre-cooked, and no way it will taste as great.

Whether you should eat it with a spoon or a fork is purely a matter of personal preference.

I use a spoon.