Have you ever eaten with Italians? When we get together for a meal, we invariably end up talking about food: “mamma makes it better”, “if only you had tried my grandmother’s recipe”, “you have to try my carbonara.” The classic scene requires a young male, who has just recently started to cook for himself, waxing poetic on said Roman pasta, on the correct dose of Pecorino Romano (not Parmigiano!) and the very refined technique of searing the guanciale (not pancetta!), before arriving at the climax of the tale: the cremina. In some cases, the unrequested lesson also includes the origin story of the pasta’s name. Now, replay this scene over and over again at every dinner party, and you’ll have an idea of what it really means to live in Italy.

Sometimes it feels like the only real national unity is what emerges under the posts of some hapless influencer cooking pasta the wrong way. Even the government, and their Ministry of Agriculture, Food Sovereignty, and Forestry, knows this, feeding the myth of Italian cuisine as linked to a monolithic tradition. And yet, behind the “Made in Italy” gourmet brand lies a great void. If there is one merit of Italian cuisine, in fact, it is that of having historically absorbed all the culinary cultures that, between invasions and migrations, have crossed the boot over the millennia. We have succeeded brilliantly in being contaminated, in reinventing raw materials that have come from afar and dishes brought from other peoples, but we have done much less well in remembering the importance of these contributions.

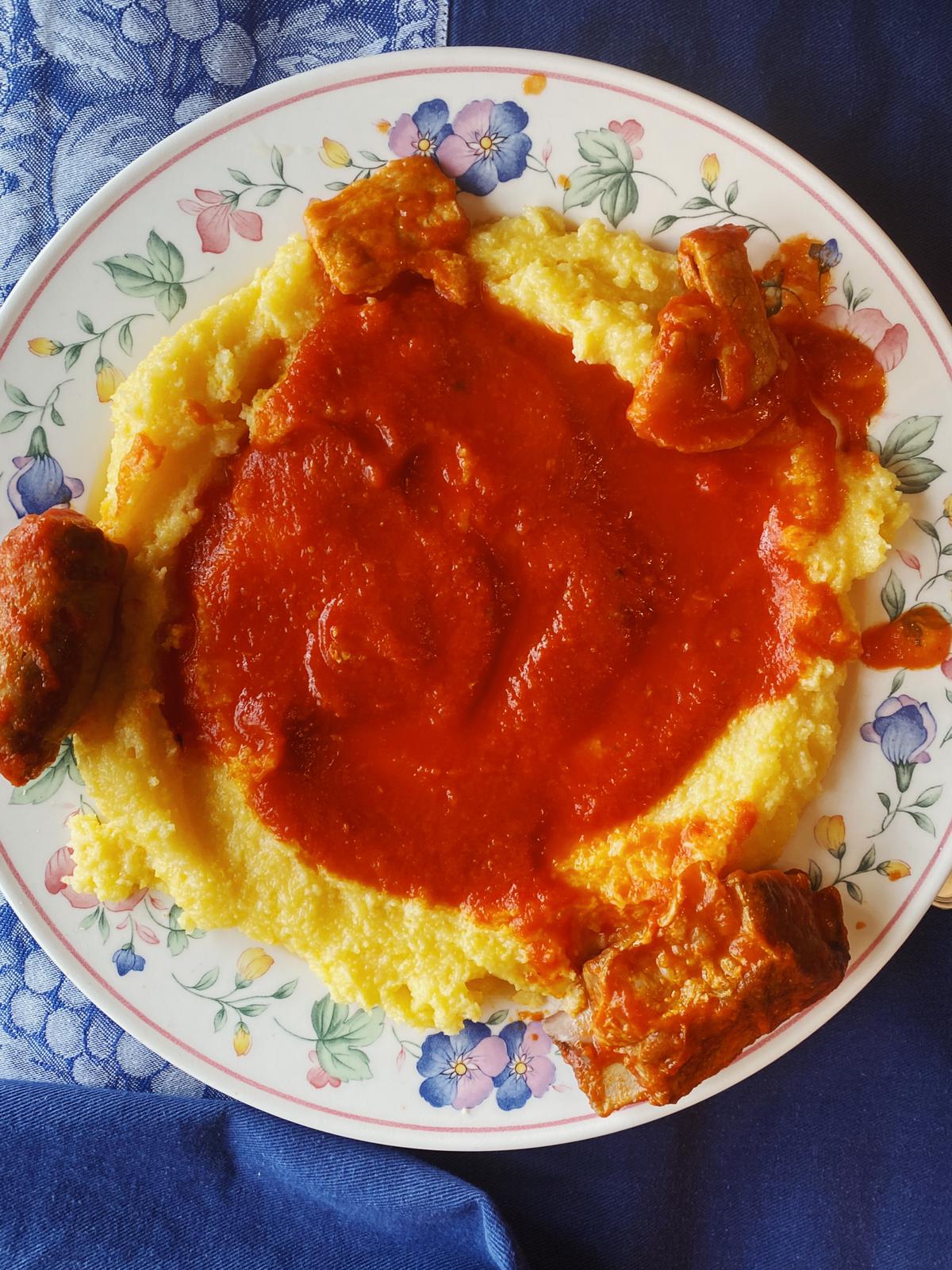

Head up north and Germanic influences can be found in the preservation of cured meats by smoking, among which speck stands out, or in hearty dishes such as crespelle in brodo, a soup made of strips of egg omelet that is eaten in South Tyrol and comes from Austria. Piedmont has a close relationship with France through Occitania, a historical and cultural region that ignores geographical boundaries and puts different versions of garlic sauce (bagna cauda, alhòli), anchovy preserves, and pastis on the same tables. Southern Italy is all a great homage to Arab culinary traditions, from macaroni to cassata, while Sardinia preserves its uniqueness in having dealt with Phoenicians, Catalans, and Romans. Venice tells of its Eastern empire with the likes of cloves and nutmeg, vestiges of the 15th century when the city-state had exclusive trade agreements on spices from India, while from the New World arrived, via Spain, previously unknown ingredients that have now been transformed into tricolor dishes, from tomato sauce to polenta.

These are cultures conspicuously missing from the narrative around “traditional” foods in Italy. In March 2023, Alberto Grandi, professor at the Department of Economics at the University of Parma and author of the book (later turned into a podcast) Denominazione di origine inventata (Invented Designation of Origin), went viral after an interview with journalist Marianna Giusti for the Financial Times. “When a community finds itself deprived of its sense of identity, because of whatever historical shock or fracture with its past, it invents traditions to act as founding myths,” he tells journalist Marianna Giusti. This was the situation Italy found itself in in the 1970s, when the speedy growth of the post-war economic boom came to a shuddering halt. (For those unfamiliar, the “Miracolo Economico” saw rapid industrial growth, particularly in cities like Milan and Turin, which became hubs of fashion and automotive design–an economic resurgence that not only fueled urban development but also revitalized the countryside, making regions like Tuscany and the Amalfi Coast popular destinations for travelers.)

The “solution” was to capitalize on the glorious past, to be researched and enhanced even at the table. The aim was attracting wealthy tourists from the western world to visit the Bel Paese, to remake the classic “voyage en Italie” of la bella vita, eternal cities, and great food. Beyond stereotypical, it’s a narrative that holds real danger, Grandi argues: “Gastro-nationalism is harming Italy. The idea that this country can live only off caciotta di Pienza [a Tuscan cheese] or tourism is an illusion. Italy cannot cope with modernity, so it wants to live in a constructed past.”

He goes on to claim that our grandparents’ generation “knew it was a lie,” that “their ‘tradition’ was trying not to starve,” and that “the philologic concern with ingredient provenance is a very recent phenomenon.” But there’s an almost divine comfort in believing in traditions, and, as Giusti writes, “Few things are more reassuring and agreeable than an old lady making tortellini.”

So, to break out of this gastro-nationalist narrative and to understand the vicissitudes that brought so much wealth to our tables, let’s turn to the less recent past and walk through an Italian menu that’s fusion without knowing it, from appetizers to dessert.

Map of the Mediterranean from 1569

Antipasto: Panadas Sarda

Let’s start with an appetizer that brings the whole of Sardinia together; from north to south, from Oschiri to Culieri, the savory stuffed pastries known as panadas are an identity-giving dish for Italy’s second largest island.

Sardinia is a land with a very ancient past: the Nuragic civilization arose and developed throughout the island between the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. We can still see some physical traces, such as dolmens, menhirs, and domus de janas (the ancient structures built by the prehistoric local cultures), but we can also see it in the food. During its thousand-year history, this civilization encountered and clashed with the most important Mediterranean cultures of the time, culminating in a final confrontation with the Carthaginians and Romans. Panadas, besides being delicious, are also a way of capturing the fruit of these contaminations.

The Sardinian panadas have direct relatives in the Balearic Islands–the empanadas mallorquinas or the formatjades of Menorca–all Mediterranean islands bound by centuries of domination, wars, and trade. The fillings vary from place to place: in Assemini they are stuffed with lamb or eel, garlic, dried tomatoes, potatoes, pepper, and parsley; in Oschiri with pork, lard, garlic, and parsley; in Cuglieri the filling is beef and pork, artichokes, broad beans, garlic, olives, and peas. The dough is made with flour, semolina, lard, olive oil, and salt, but it is also the shape that confirms the relationship with the Spanish islands, with the edges pinched into a sort of crown.

A practical way to cook, store, and transport food, the dish was very convenient for Arab and Spanish people, always on the move around the Mediterranean. This is probably why variations of panadas have gained popularity (and several names) in other parts of Italy. In Sicily, after all, the customs of the Arabs were picked up by the Spaniards, masters of the island between the 16th and 18th centuries, and led to a flourishing of variants: in the Catania area, they are called scacciate and in Agrigento, mbigliulate. Ragusan lamb impanata is more like a pie. Round and smaller are the Modican pastieri, and in Scicli, the ‘mpanate prepared between March and May (the cuttlefish fishing period) are stuffed with cuttlefish, potatoes, rice, tomato sauce, toasted breadcrumbs, salt, pepper, garlic, and parsley.

Panadas; Photo by EnGuillem

Antipasto: Scapece

That perfect kick given by the balance of vinegar, white wine, sugar, and salt is a potion found applied to foods all over the country. In Naples, there are courgettes (but also aubergines and anchovies) alla scapece; in Gallipoli, fried fish is flavored with saffron and soaked in vinegar; in Abruzzo, we find sardines scapece alla vastese and in the province of Salerno, anchovies alla scapece di Cetara. Yet again, the names change, but the method of frying and preserving in vinegar is the same, found in Piedmont’s carpione (here everything counts: eels, chicken steaks, courgettes, and even eggs) or in Veneto’s in saor.

As much as each of these recipes has a respectable local history, the technique behind them is of Arab origin, probably coming to us in Italy from the Hispanic tradition. Brought to Spain during the conquest of 700 AD and then spread to the ports of the Mediterranean thanks to the Spanish fleets (which is why it also managed to reach northern Italy, passing through Genova and becoming “carpione”). The name “scapece”, after all, is of Spanish derivation: from “escabeche” (or “escabetx”, in medieval Catalan), which in turn comes from the Arabic-Persian “sikbaj”. Of course, the Romans also had their own way of preserving fish in brine, while the Venetians with their famous saor muddied the waters even more by preserving grilled fish in vinegar as early as 1300 AD, adding herbs and spices from their trade with the East.

Sarde in Saor; Photo by Manos Chatzikonstantis, Styling by Michail Touros

Primo: Spaghetti alla Bottarga

Our menu here straddles antipasti and primi, with bottarga going well on everything, whether it be crostini or the omnipresent spaghetti alla bottarga. But wherever you put it, know that it was the Phoenicians who brought this delicacy to Sardinia as a bargaining chip, which in Arabic was called battarikh (salted fish eggs). The Phoenicians established significant trading settlements in Sardinia around the 9th century BCE, introducing advanced agricultural techniques, pottery, and metalwork and influencing eating habits.

Three thousand years ago, they began processing mullet in their Sardinian settlements of Tharros, Nora, Cagliari, and Sulci, close to what is now the main production area of the renowned “Sardinian caviar”. But the origin of bottarga could be even more ancient, dating back to the the period of the Old Kingdom (2700 – 2192 B.C.); a bas-relief from this period in the necropolis of Saqqara, Egypt, seems to depict a man cutting open a mullet with a knife, next to two objects that look like fish egg sacs. The Phoenicians were great navigators and merchants, and they have had the merit of transporting bottarga and this technique around the Mediterranean, finding in Sardinia (but also in Sicily and the Maremma) the perfect spot to develop the technique.

Now, it’s time to hit the sore spot. Is pasta really Italian? Given the abundance of formats and types of pasta in the country, it’s impossible to generalize. There is no lack of documents proving the presence of fresh pasta as far back as Roman times, and the debate over whether spaghetti is Chinese or Italian is often settled on a level playing field: it is indeed possible that in two different regions of the world, raw materials were treated similarly. But as far as pasta is concerned, an important contribution comes from the Sahara desert. The Berbers had to find a stratagem to preserve the carb in the torrid climate and did so by drying strands of durum wheat pasta arranged in parallel: the mukarana, a word that later became macaroni, despite indicating a long and thin kind of pasta, more similar to spaghetti.

Primo: Pasta al Pomodoro

The tomato arrived in Italy, specifically in Pisa, on October 31st, 1548, when Cosimo de’ Medici received a basket of tomatoes grown from seeds gifted to his wife, Eleonora di Toledo, by his father, the Viceroy of Naples. In the beginning, it was an ornamental plant and thought to be poisonous. Although the perfect bond between pasta and tomato sauce seems almost sacred and difficult to dissolve, the first evidence of this union only appears in 1692, when the court cook of the Spanish Viceroy in Naples, Antonio Latini, mentions a “Salsa di Pomadoro, alla Spagnuola” in his recipe book, pointing to Spain as the real creator of tomato sauce. This is, after all, understandable, since Spain was the access point for products coming from the New World, leaving us only the boast of having refined it properly.

Secondo: In Zimino

Perfect for an autumn day in the Ligurian hinterland, “in zimino” describes dishes where a main ingredient—such as cuttlefish, chickpeas, tripe, or cod—is simmered with chard and tomato sauce. The name likely comes from the Arabic word “samin”, meaning “dense sauce,” fitting since these brodetti pretend to be light but warm and regenerate in no time, best enjoyed with slices of garlic-rubbed toast. (The term, in Sardinia, indicates a dish of entrails, whose particularly nutritious consistency also holds true to the dish’s etymological origins.)

These Ligurian dishes tell of a time just before the great glory of Genova as a maritime republic. Between the 9th and 11th centuries, Saracen raids and trading activities had an impact on the Ligurian coast, particularly the areas of Genoa and the Riviera di Ponente. The Moors established trading bases and, in some cases, controlled short stretches of coastline. The cities of Liguria soon became centers of exchange between the West and the Arab world, and the Italian region’s gastronomy adopted ingredients, cooking techniques, and terms from those that landed on its shores. Arab expansion was eventually thwarted by the maritime republics, particularly that of Genova, and by the 11th century, Muslim influence in Liguria faded–though it left its fragrant mark on the menus of trattorias.

Dolce: Cassata

Sicilian desserts divide the masses: there are those who adore its unapologetically sweet flavors, the hands sticky with honey and the predominance of dried fruit, and there are those who somewhat fear it, so ready to overwhelm the palate with its baroque sugars. But here again, history speaks for itself: southern Italian desserts, and Sicilian ones in particular, have their roots across the sea.

The island’s pastry could not be what it is without the Arabs; it was they who introduced the candied fruit, bitter orange, and almond paste that characterize cassata and cannoli. Sorbet also derives from Arab sherbet: a mixture of citrus fruit juice, cinnamon, vanilla, and crushed ice to which the Arabs added cane sugar.

Cassata takes a step further, gathering the best from the various dominions to become the island’s flagship dessert. Its origins date back to the time of Arab domination in Sicily, between 831 and 1091, when they introduced the use of ricotta and candied fruit, but the recipe has also incorporated elements from the Normans. It was during their reign (1061 to 1194) that the dessert became more elegant, with the introduction of sponge cake and marzipan.

Cassata; Photography by Guy Ambrosino

These are just a few examples of the never-ending dishes inspired by and courtesy of other cultures; we could follow countless invisible paths made of more-or-less verifiable stories, trade routes, crusades, and wars. One of the things we have done best, in Italy, is to synthesize the richness that the Mediterranean has brought us over the centuries. To stop doing so, to lock ourselves up in nationalist designations, in defense of an imaginary history, would be a supreme failure. So, finally, a last piece of proof that might shake your certainties to the core: in addition to the contributions of the South Americans (tomatoes), pizza could not exist if it were not for the people of India. Yes, the buffaloes that proliferate in the plains of Campania and produce the region’s famous mozzarella arrived in Italy only after wandering halfway around the world. The Sumerians imported them in 2500 B.C. after learning about them from the peoples of the Indus valleys; after traveling through Mesopotamia, Turkey, and Eastern Europe, the Eurasian Avar populations brought them to Campania.

Isn’t it amazing how just a sprinkle of research can turn a “100% Italian” menu into a beautiful cross-cultural tale?