“Milano è positiva, ottimista, efficiente” (“Milan is positive, optimistic, efficient”), a man’s voice murmurs huskily, over a saturated video collage of Milan’s yuppiest set. This, the voice croons, is a city that “rinasce ogni mattina, pulsa come un cuore” (“is reborn every morning, that beats like a heart”). Forget the slow living of the Italian “dolce vita”, here we are shown the roar of traffic, technicolor lights, the clamor of businessmen and women in packed bars. This is a city in the midst of an economic boom, a city where people work hard and play harder. “Milano,” the voice continues, “è da vivere, sognare, e godere” (“to live, dream, and enjoy”). The camera pans out to a shot of Milan’s skyline, high rise buildings on proud display. Out from the pulsing glow rises a bottle of Amaro Ramazzotti. “Milano da bere,” the voice concludes, that now notorious slogan flashing across the screen.

The 1985 advert for Amaro Ramazzotti, the Milanese bitter liqueur that is one of the oldest in Italy, is emblematic of Milan’s “Swinging 80s”, a time defined by the collective desire to clamber away from the horrors of the 1970s’ anni del piombo (years of lead) and pursue socio-economic recovery. And the hope placed in this new decade came to fruition: the 80s in Milan were characterized by financial prosperity, upward social mobility, and a rampant desire to live the newfound high life. The advert shows Milan as the rest of Italy saw it at the time, but also as the Milanese saw themselves: hard-workers and networkers, championing hedonism and ambition in equal measure. It is little surprise, in a booming social context where the pipeline from office to bar was well lubricated by the closest cocktail, that the advert reveals a drink to be at the city’s nucleus. And not just any drink, but an Amaro.

Milano da Bere swiftly became an expression used to encapsulate the zeitgeist and though the bitter drink was the shining star of 80s Milan, the city’s relationship with “Amari” and bitters goes back well over a century, to the early 1800s.

These two drinks differ: “amaro”, the Italian word for bitter, refers to a kind of herbal liqueur that is traditionally served as a digestive after a meal, while “bitters” are usually added to a cocktail, drunk before a meal in the aperitivo tradition. Italy is renowned for the quality and variety of both amari and bitters, boasting the largest selection of the drinks commercially available. The popularity of bitter drinks like the Aperol Spritz, Campari Spritz, and the Negroni means that the use of bitters in particular has spread well beyond its northern Italian origins, along with aperitivo itself, that well-loved tradition that is understood to have originated in Turin in the late 18th century, brought on by the rising popularity of the newly-invented Vermouth. And yet, while aperitivo may have been born in Turin, it grew up in Milan.

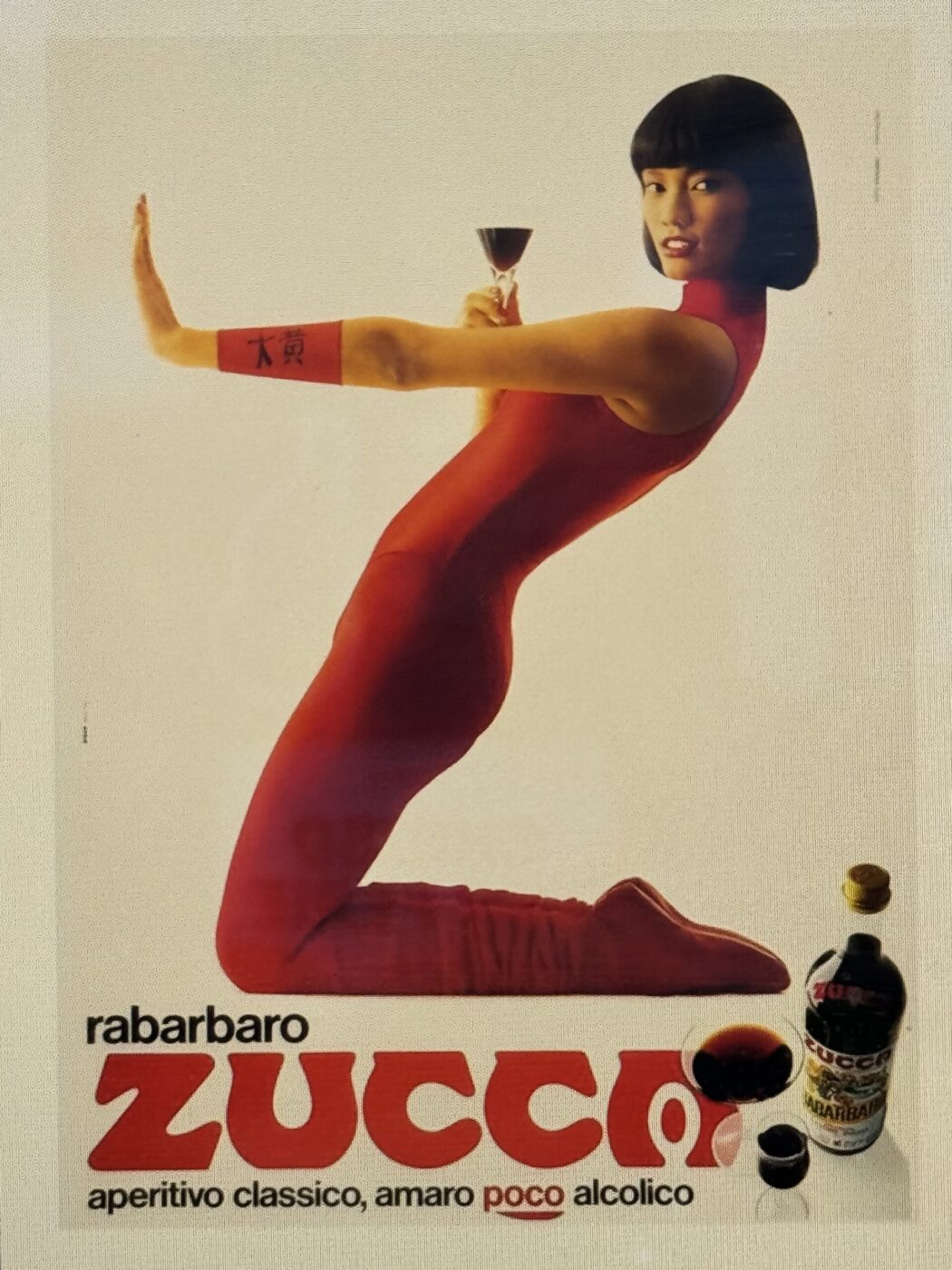

1985 advertisement for Amaro Ramazzotti

Milan’s First Amari: Ramazzotti, Rabarbaro, and Fernet

Milan’s reputation as capital of the aperitivo and its longstanding connection with the bitter aperitif arises in part from the wealth of bitter drinks that the city has produced. The popularity of Vermouth in Piedmont was swiftly followed by the invention of Amaro Ramazzotti in Milan in 1815, by Bolognese pharmacist and herbalist Ausano Ramazzotti. He had moved to Milan in the early 1800s and started up a small laboratory where he experimented with blending exotic and heady ingredients, wanting to distill Italy’s history with herbalism into a drink that could be enjoyed at any time of the day. The exact details of the concoction remain a family secret, though it is known to combine 33 spices, herbs, flowers, and fruits, and include Sicilian orange peel, star anise, cardamom, and cloves. A few decades later, in 1848, Ramazzotti opened a bar in Via Canonica, where he was known to offer the “amaro” to customers instead of coffee. Its popularity boomed; the family company Ramazzotti Fratelli was established 10 years later, almost a century before an advertisement sealed the amaro’s fate as forever synonymous with an iconic era of Milan’s history.

Amaro Ramazzotti was a hit, and that was just the start. In 1845, pharmacist Ettore Zucca was experimenting with herbal ingredients in an attempt to remedy his wife’s digestive problems. Pleasantly surprised by the drink’s distinctive taste, so named “Rabarbaro” for its flavoring of Chinese rhubarb, Ettore decided to add alcohol and offer out the homemade concoction to his friends. What started out as a workshopped cure-all quickly became a popular Amaro amidst Milanese society, and Ettore’s son, Carlo, successfully established the drink as a commercial business, further expanded into national and international territory by grandsons Emilio and Gerolamo. The drink’s ubiquity amongst the bars of Milan is encapsulated by the wordplay of its perhaps most notorious slogan: “Il Rabarbaro Zucca si trova nel bar come il ‘bar’ si trova nel RaBARbaro.” (“Rarbarbaro Zucca can be found in the bar just as ‘bar’ can be found in RaBARbaro.”)

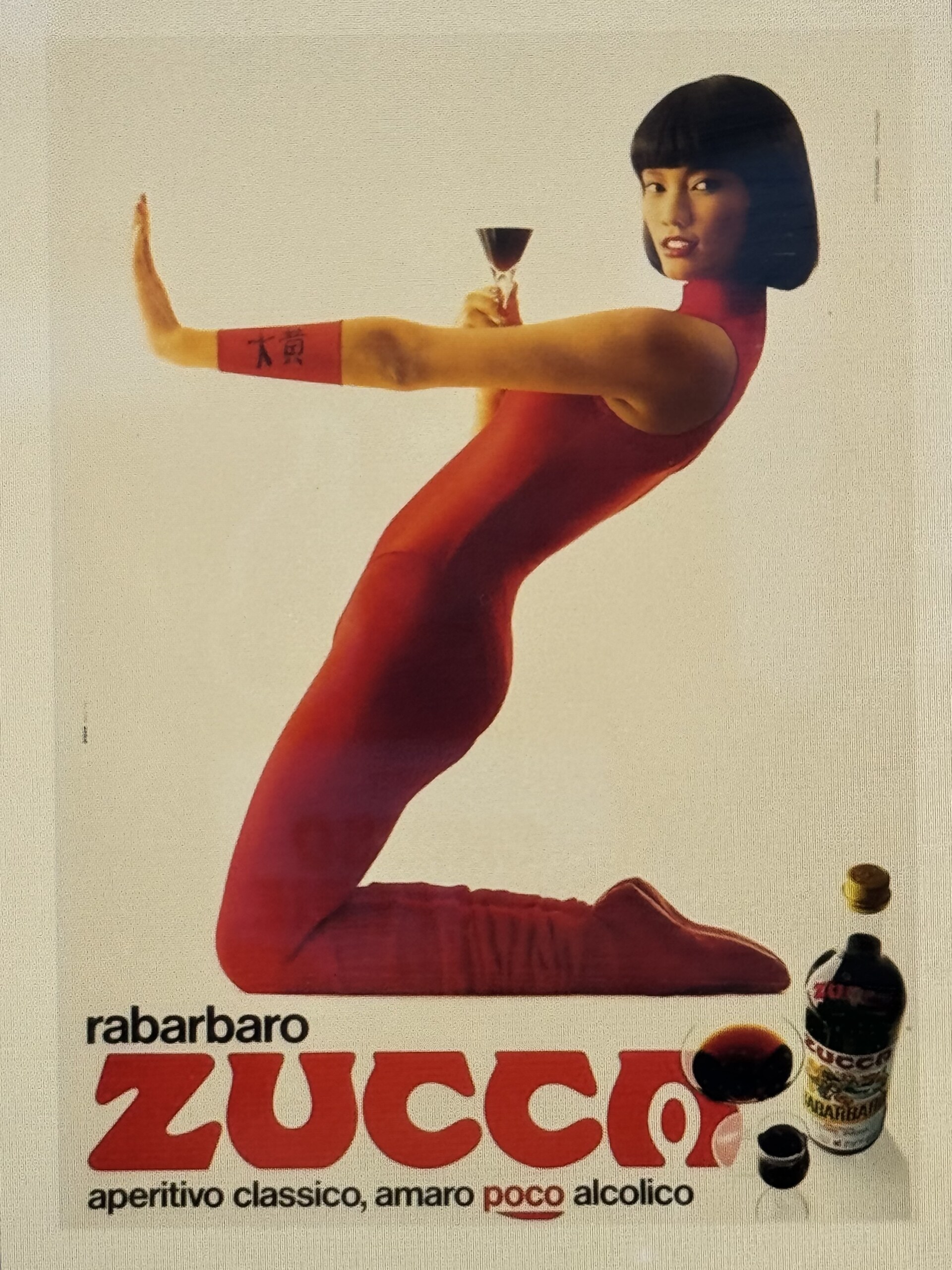

Nora Ariffin in a vintage advertisement for Rabarbaro Zucca Milano

Such experimental workshopping of new medicinal remedies was a common nascent of herbal liqueurs. Fernet-Branca, an amaro composed of 27 herbs and spices, was founded by Bernardino Branca in the same year. The self-taught herbalist had been experimenting with medicinal remedies in his lab-turned-distillery in Porta Nuova, and initially sold the drink as a “pick-me-up”: a tonic to promote general well-being, as well as a cure for fever, cholera, and menstrual pains. Its praise from local doctors led to increased popularity, and in 1905 it was christened with its distinctive art-nouveau logo: an eagle clasping the bottle in its claws, with the sphere of the world hovering tantalizingly below. The globe is an apt feature; much of this drink’s consumption happens overseas, where it is particularly popular in Argentina drunk “con Cola”, and in San Francisco, where the Amaro is curiously drunk behind the bar in a symbol of institutional solidarity known as the “bartender’s handshake.” This recipe, too, is a family secret, with its hazy apothecarist beginnings setting the scene for the intrigue of the formula, said to be kept in a company safe that can only be accessed by the chairman. In 2009, the Branca Collection Museum was opened in the company’s historic production facility in Milan; a testimony to the legacy of the brand and its significance in Milanese and Italian history.

Fernet-Branca; image from the History of Medicine (IHM) and contributed by Fratelli Branca distillerie

Campari Comes Along and Bitter-Based Aperitivo Booms

While the invention of Amaro Ramazzotti, Fernet-Branca, and Rabarbaro Zucca firmly situated Milan as a city of amari, it was with the birth of Campari that its status as capital of the aperitivo truly took off. The jewel red drink, its hue once deriving from crushed cochineal insects, was invented in 1860 by Gaspare Campari, who owned a cafe in a small town called Navaro near Milan; it was the first of its kind. Gaspare was known to regularly play with flavor combinations, serving up unique drinks to his customers. One drink, initially called “Bitter all’uso d’Hollanda”, an ode to the Dutch bitter that had inspired him, became a particular favorite. The not-so-catchy name was swiftly shunned, and the drink affectionately re-baptised “the bitter of Mr. Campari”, later shortened to the simple, illustrious “Campari”. Its popularity allowed Gaspare to move to Milan in 1867, opening up a bar in Milan’s Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, the city’s newly constructed social and cultural hub. The birth of Caffe Campari was shortly followed by the birth of Gaspare’s own son, Davide, who made history as the first citizen to ever be born in the Galleria. Gaspare continued to experiment with mixing drinks behind the bar, but it was his Campari that had started to draw in the crowds.

Gaspare died in 1882, but Campari continued to grow under the watchful gaze of Davide. The booming sales meant that in 1892, the first Campari factory was opened in Milan, and in 1915, Davide opened the Camparino bar in Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, an ode to the brand’s origins. The bar was Caffe Campari’s newer, cooler little brother, and was installed with a soda water system; an innovative addition that meant Campari and soda could be served as a perfectly chilled mixed drink to eager customers. The modern twist on the popular classic brought the concept of the mixed drink, to be enjoyed before dinner, into the mainstream.

Camparino became the city’s aperitivo hot spot, and the cult of the cocktail took Milan by storm. Campari became a key component of new, glamorous cocktails like the Americano and the Negroni. (The latter was described by Orson Welles in 1947 as a “new drink” in which “the bitters are excellent for your liver, the gin is bad for you. They balance each other.”) The Negroni Sbagliato, a later twist on the original cocktail, was invented in Milan’s own Bar Basso in 1972, when bartender Mirko Stocchetto was asked to make a Negroni, and accidentally added prosecco instead of gin.

Just a decade later, “Milano da bere” entered with vigor, ushering in a period that was not only emblematic of Milan’s innovative history with alcohol, but also firmly set the city apart from Italy as it existed in the national imagination. In a country where “il dolce far niente” is the status quo, Milan’s Swinging 80s revealed the Milanese to be cut from a different cloth: here, time was money, and money was pleasure.

Milano da Bere, Today as Yesterday

In Milan now, Bar Basso and Camparino remain the city’s most famous aperitivo spots, duly serving up the classics for those seeking a taste of Milan’s past. The Navigli District promises a more contemporary drinking destination, where the canals are lined with bustling bars and waiters wobble trays laden with drinks as bright and colorful as insects. Plunge into Milan on a balmy evening, and the city is alight with the sound of voices, the clinking of ice cubes and glasses. It has been over 40 years since the notorious Ramazzotti advert came out, and Northern Italy is far from experiencing the financial boom of the 1980s. And yet, this continues to be a city that has a rhythm akin to a heartbeat, that does not exist in easy slumber, but is reborn with new vitality every morning. This is still the city where people “live, dream, play”, and, come the swelling of dusk, where they drink.

Click here for a comprehensive guide to drinking in Milan, with both old- and new-school places to slurp down on the city’s finest cocktails.