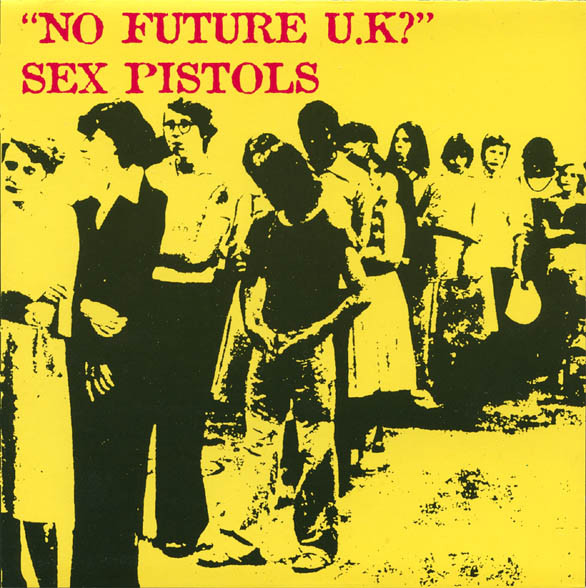

Barona, Rozzano, Gratosoglio, Corsico, Trezzano, Baggio: these are the suburbs that break down at the end of the 1970s at the hands of inflation, housing shortages, and widespread violence. The great utopias that had moved young people in the previous years crumble, and the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro in 1978 acts as a gravestone for many political movements, which succumb under the weight of the decade’s brutality. The youth clubs based on political values disintegrate, and the myth of worker solidarity is no longer enough to convince young people to toil in factories for the rest of their lives. This hangover from the great ideals is the perfect petri dish for a slogan that comes from England: “No Future!” Shouted by the Sex Pistols, it immediately makes sense to all those boys from the Milanese suburbs who no longer want to believe in the fairy tales of a better world, given that the one they live in every day is always the same, full of poverty, degradation, violence, and death. And so they push towards the city center, picking up the legacies of the artistic Brera and occupying the empty spaces of the counterculture with anger. This is the beginning of Italy’s punk movement.

Pet Accessories are Cheaper: The Punk Look

Milan, where factories are at their most populous, is the nexus of punk in Italy, but some groups also form in Bologna, Brescia, and Turin–though all overlap when it comes to looks. “Hair is fundamental – you have to keep it straight – upright – like pins or sharp studs – it is an important symbol – stiff ends mean hate – hair must stand upright – pissed off at the whole world,” writes Marco Philopat in Costretti a sanguinare. Racconto urlato sul punk (Forced to Bleed: A Screaming Tale of Punk); one of the city’s first punks, member of the punk group HCN, and co-founder of Virus (the squat that consolidated the punk movement in Milan), Philopat is the premier on-the-ground source of punk culture in 1980s Italy.

Clothes, too, he recalls, must be like punches thrown at the regular people who stop to stare: black, red, leather, pins, studs and spikes, pet accessories (the latter cost less). It is a question of attitude, a constant choice to howl to the world that you are not like everyone else, that you do not want the same world, and that you are ready to destroy it in order to make another one with your own hands; for “do it yourself” is the second slogan that marks the punk movement.

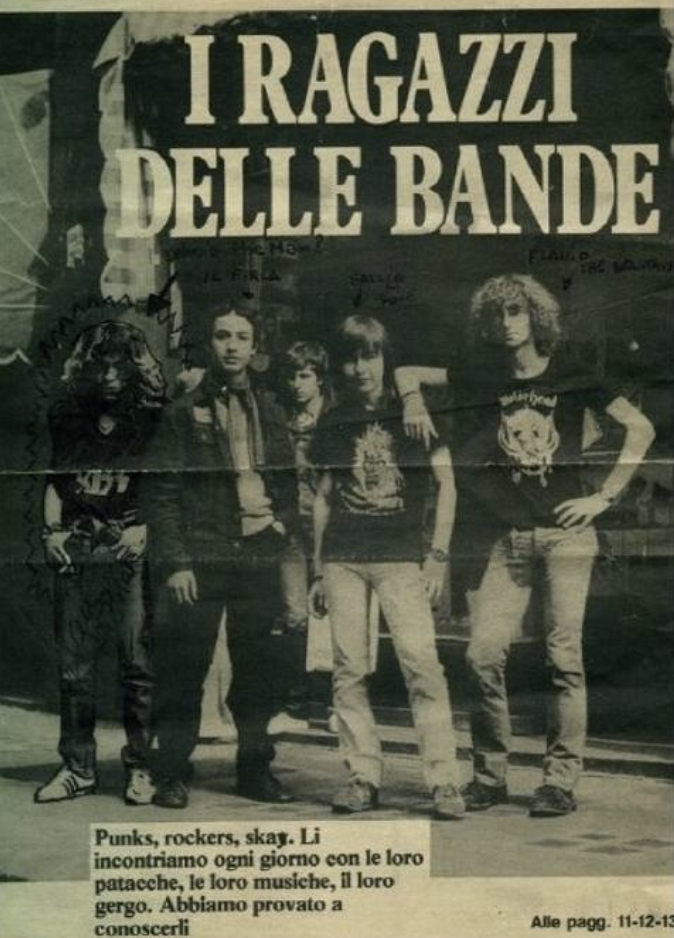

In early 1980s Milan, punks are not the only group to seek a new identity, one tied to individuality and no longer to the “collective good” as their parents and grandparents had. And each group makes their choices explicit through clothes: “In via Torino with the stoners – those who wear Strega jackets – the fashionable shop in piazzale Lagosta – used jeans wide at the waist – medium-long hair with curls or bobs – pointed leather shoes… By the comrades they are called ‘fioruccini’ – because they meet in front of the designer’s shop – where DJs play disco music every afternoon… The stoners – they come from the outskirts – they also get stoned – but they don’t want to hear about politics,” writes Philopat. The “mods” listen to ska and wear tight-fitting tailored suits and parkas to protect them while riding their mopeds; the “metalheads” sport black leather jackets, boots or trainers, jeans, chains and studs, long hair and tattoos; the “goths” are “young people who dress exclusively in black – clean-cut with pointy shoes or shiny leather boots – wear Cure or Joy Division badges and a few upside-down crucifixes,” while the “skinheads”, soon to be identified as bigots and linked to extreme right-wing parties, are recognizable by their shaved heads and Fred Perry polo shirts.

A Subculture Beyond Style

The punks, however, want it to be known that their movement is not just a fashion choice; on the contrary, the real punks are fighting to prevent capitalism from swallowing up this counterculture. They do so by boycotting the concerts of bands they adore, but who are using punk to achieve success–the Clash in Bologna in ‘80 or Black Flag in Baggio in ’83–and by developing ideologies that animate different factions. Philopat’s punk, for example, is that of Crass, a vegetarian British anarchist collective united in a commune and committed to the fight against fascism, nationalism, sexism, racism, capitalism, and wars.

Reaching this anarchic awareness, however, is not an easy path. “Fuck it, we were fragile because we hadn’t studied, ignorant as goats, very young, sons of proletarians or people expelled from the factory,” Philopat told Rolling Stones, noting that many punks were no older than 17. “These situations had driven many to reject society and find themselves on the streets.”

One of the most concrete problems for the Milanese alt-groups is the lack of gathering spaces, which increases tensions between the various gangs and makes the streets of the city a map of underground cultures. Punks walk around the center, passers-by insulting them because of their dog collars, left-wing comrades wanting to beat them up because they think they’re fascists, parents trying to beat them “back to normal” (many do so during the week, for fear of losing their jobs), and heroin taking one out of every two. Saturdays are a refuge, when the Senigallia flea market is held along the Darsena. There, they meet like-minded people, sniff each other out, and exchange information about the “Real Punk”, the one from London, Zurich, or Berlin.

In search of a community space, the first punks meet at Santa Marta, a social center accessed via the narrow Via Bagnera, but cohabitation with politically committed groups doesn’t last long and soon the punks are back on the streets, in front of the New Kary on Via Torino (the only record shop where you could listen to the Sex Pistols and the Ramones), at the Senigallia fairground, in Sempione park, at the Magenta bar or the Concordia pub.

The creative arm of the movement is housed in the Vidicon, a squat, where the first punk fanzines are born. The first is “Dudu”, from ‘77, transformed the following January into “Pogo”, while in March ‘79 ”Xerox’ is given to the press, which screams “We are the Dudu – we are the rage – we want to rebel now! We reject factory work – and above all we frontally attack the logic of militancy – the personal is political!!! – After all, we don’t give a damn – not even about punk music or punks – we only care about the abolition of the future and memory.”

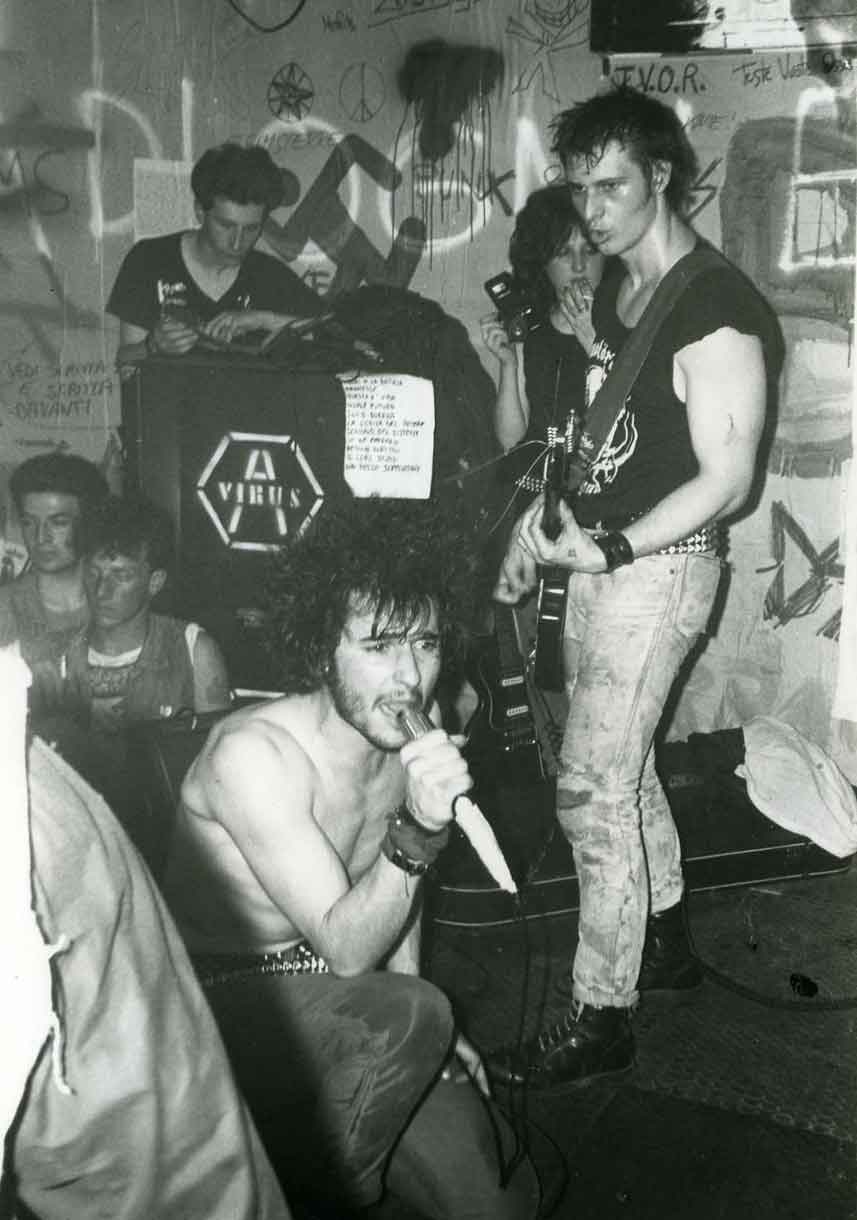

The Hardcore punk band Wretched in concert at the Virus community center

Safe Havens from Heroin: Virus’s Vibrations

It’s during these very same years that opiates spread among an unprepared population, and overdose death rates skyrocket; a 1992 research report by the British Journal of Addiction estimated 28,000 users in 1977, a figure that, by 1982, had jumped to 92,000. And despite the press’s desire to portray punks as self-destructive and dangerous, it is precisely the need to wrench friends away from the easy choice of heroin that gives rise to the first real punk shelter in 1982: Virus, in an abandoned factory, launched with “PUNX AGAINST APATHY FOR SELF MANAGEMENT – CONCERT AGAINST HEROIN IN THE OCCUPIED HOUSE OF VIA CORREGGIO 18.”

The punk squat soon becomes the home for all those young people, often minors, who come from the suburbs and the provincial territories to escape from factory life, from patriarchal families, from a future that already used to suck but that now no longer exists. It’s a space with music rooms and kitchens, but, above all, beds, because “punk represented a difficult but necessary choice of field, a lifestyle capable of saving us from the prevailing reflux and from the famous Milan ‘da pere’ because the ‘da bere’ was reserved for the upper class,” writes Philopat.

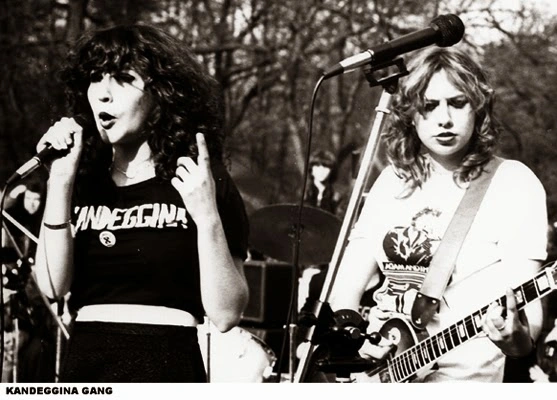

And then there are the squat bands, who learn the simple chords of “I Wanna Be Your Dog” and then take turns on stage making noise. The musical groups of those years are many, with bases in Milan, Turin, La Spezia, Pisa, and Bologna–Kandeggina Gang, 198X, HCN, Raf Punk, Nabat, Naplam, Holy Family, Wretched, 5° Braccio, Fall Out, CCM, Antigenesi. From one city to the next they play in the squats that begin to dot the peninsula. Famously, CCCP, considered frauds who are capitalizing on punk, is kicked out of a New Year’s Eve concert with rotten onions to their faces.

Kandeggina Gang

We get a glimpse of Virus’s philosophy through the documentary Virus Milano, which interviews members of 5°Braccio. “Big ideologies are useless,” they say. “I feel like being a pain in the ass and working on the immediate, on all the needs there may be. It’s pointless to talk about the future and worlds to come if every day you must live the same shit, a job and a world you didn’t choose. We can’t change everything right away, so the only thing is to just annoy the shit out of it.”

Letters of complaint from the neighborhood about the loud music are common; the neighborhood tension reaches its peak in April, 1982, with the “Spring Offensive”, a three-day punk event against police repression, when more than 50 bands from all over Italy play in a continuum of noise and hallucination.

Virus lasted a total of seven years, with the punks eventually getting evicted, but its energy spread throughout Milan, reached Turin, Florence, and Bologna and, if you look hard enough, it can be found in the most creative flashes of mainstream culture, contaminated in spite of itself by the relentless Virus.

The building in Via Correggio was the last bastion of a working-class Milan, soon to be devoured by housing speculation and the frenetic pace of capitalism. It now seems impossible to imagine the delirium of the Virus among the spotless walls of the neighborhood. Perhaps those punk kids knew it: in remembrances like those of Philopat, one finds all the fragility of a generation mown down by a lack of prospects and heroin, but also the avant-garde visions of those groups, whose thorns, no matter how spiky, did not serve to protect them from the future, which eventually arrived.

“We are the corpses / of this shitty city / where we can’t live / where we never do anything / where the things we have left / are anger and despair / everything else they’ve imprisoned us / everything else they’ve seized from us. Because anger and despair are synonymous with rebellion.” –“Rabbia e disperazione” by 5° Braccio

If you’d like to hear more from this generation of Italian punk, check out this playlist or any of the bands listed below:

- Negazione

- Raw Power

- Bloody Riot

- Nabat

- Declino

- Indigesti

- Crash Box

- Nerorgasmo

- Kandeggina Gang

- Blue Vomit

- Wretched

- Impact

- Contrazione

- CCCP

- Cheetah Chrome Motherfuckers

- Linton Kwesi Johnson

- Gheddafi Mohican

- The Carnival of Fools

- Not the Same

- Antigenesi

- Decibel – Champagne Molotov

- Chrisma (now Khrisma)

- Jumpers

- Adam and the Ants

- Siouxsie

- The Stooges

- Kos Rock

- Rudie Can’t Fail – The Clash