My first encounter with Poste Italiane was in December 2024. I stepped through the concave doors of the Piazza Bologna branch in Rome to complete a simple yet spiritually harrowing task: apply for my permesso di soggiorno, the Italian residency permit dreaded by all and mastered by none.

My soggiorno application felt less scary compared to the Piazza Bologna branch with its vertical marble slabs and Fascist-era grandeur. Designed by Italian rationalist architects Mario Ridolfi and Mario Fagiolo in the 1930s, it looks less like a civic institution and more like a temple, meant to impress and scare in equal measure.

The application was allegedly straightforward. All I had to do was collect a kit, only available in person at the post office, fill it out with near-biblical precision, and return it to the very same place. Easy.

Except it wasn’t. Italian bureaucracy, I would soon learn, has a life of its own. Every process is a riddle, an excruciatingly frustrating Rubik’s Cube with any number of possibilities. Little did I know that, at the end of an hour-long wait, I would be gently informed by the post officer that I had picked up the wrong form, filled it out the wrong way, and brought it to the wrong institution—followed by elaborate directions to the Questura. And it wouldn’t be the last time I’d go through something like that—both in Italy and at Poste Italiane.

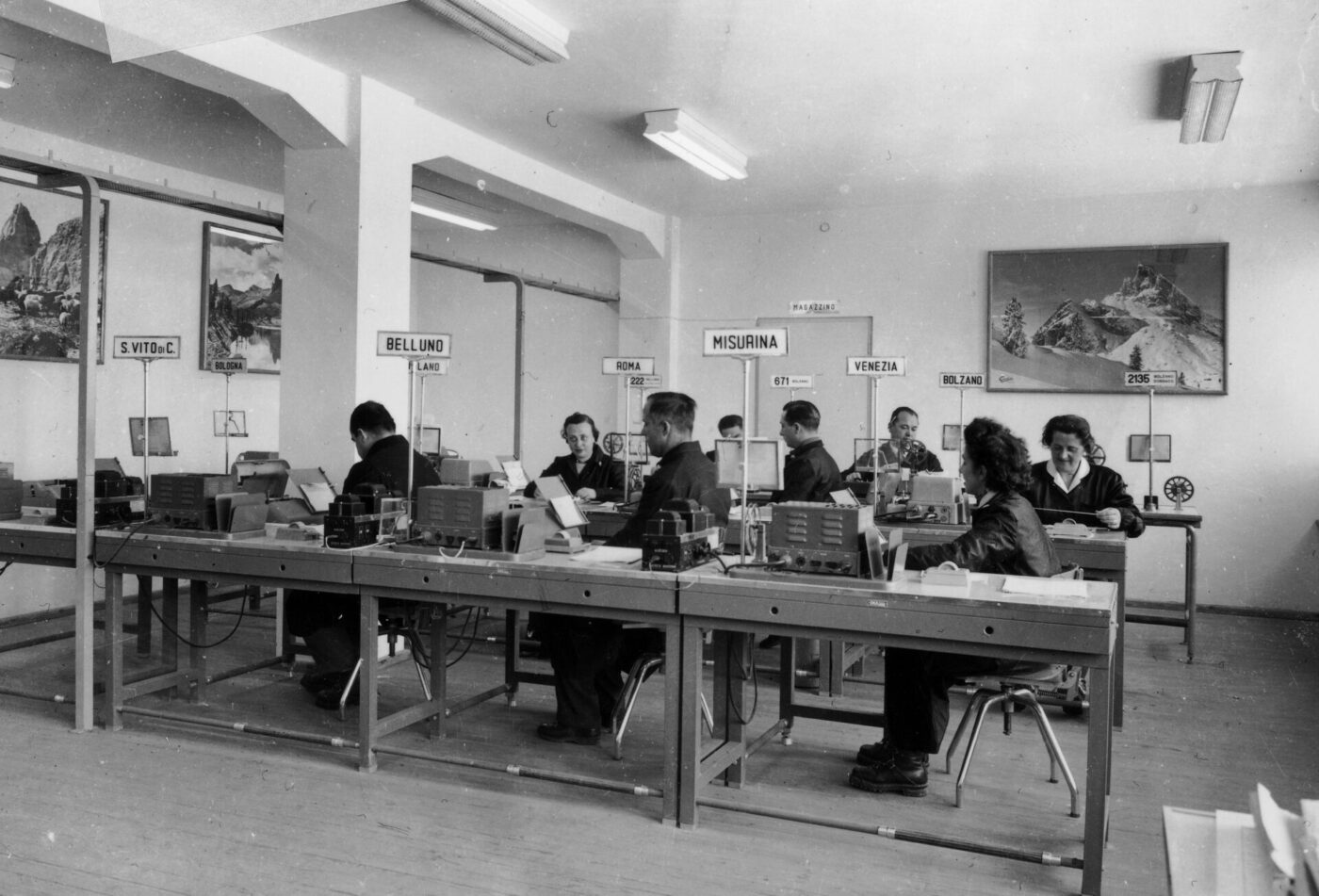

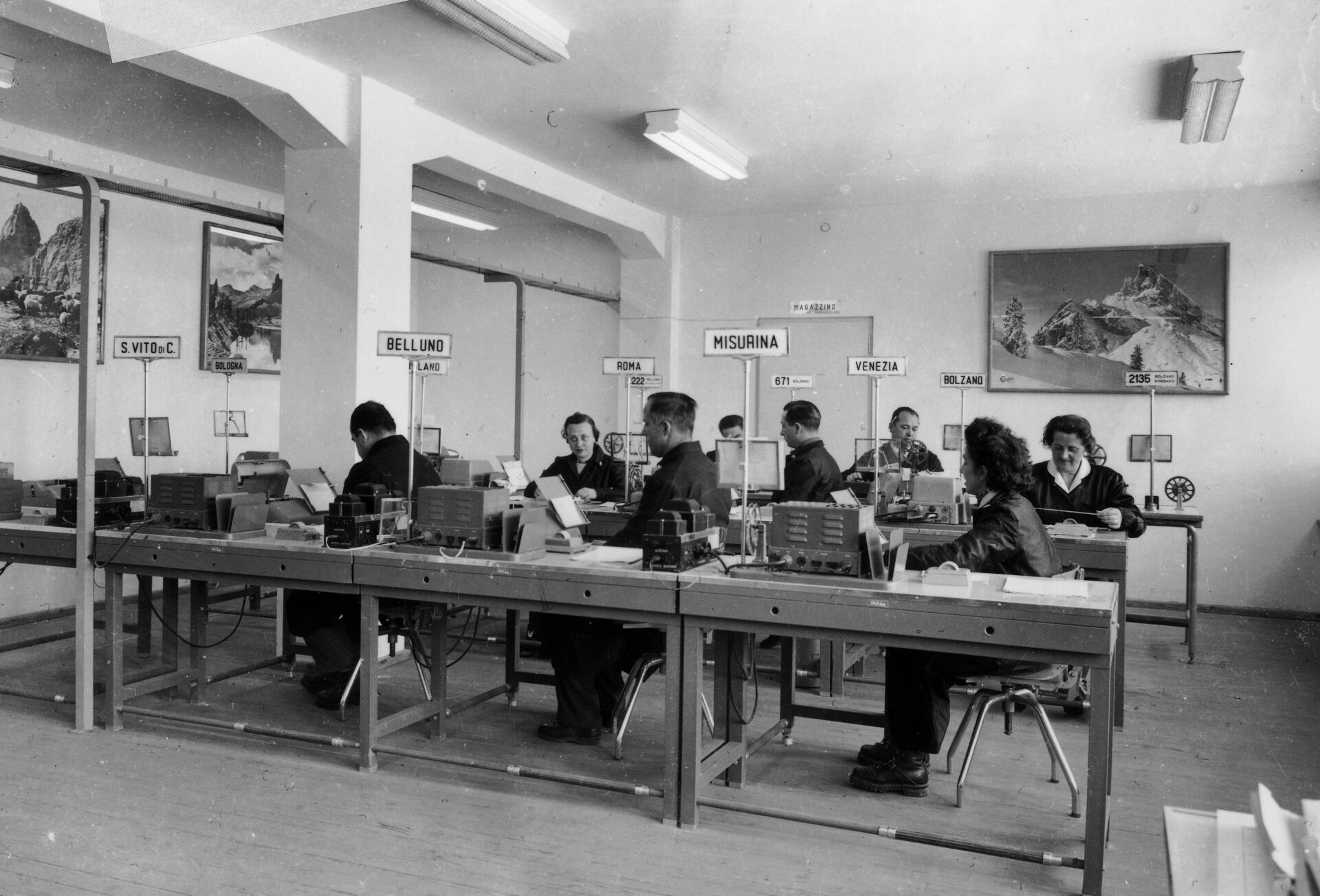

Poste in 1960; Courtesy of Poste Italiane

Building a Nation One Mail at a Time

When you walk into any Poste Italiane branch, you’re standing in one of Italy’s oldest and most enduring institutions. Founded in 1862, just one year after Italy’s unification, Poste Italiane played a critical role in connecting a fragmented Italy, from Piedmont to the Papal States. Although declared a unified state, Italy was still a patchwork of former kingdoms, noble families, and territories—each with its own dialects, customs, and allegiances.

The creation of a single national postal system wasn’t just a matter of infrastructure but also ideology. A nation had been declared, and now it needed to feel like one all the way from the Alpine North to the agrarian South.

Some changes were relatively straightforward: standardized addresses, Italian-language forms, and a unified postal code system. They were all designed to extend the reach and improve the efficiency of the newly formed Italian state. (Whether Italy has ever truly become an efficient state remains a matter of national debate—even today.)

Others were harder. The emerging republic demanded a lot from its citizens. Men across the country began receiving conscription notices, summoning them to suppress uprisings internally or to fight its wars abroad. For some, these letters were a devastating reminder that they would soon have to leave their loved ones and communities; for others, they offered a sense of duty, perhaps even honor, in serving a nation they were only just beginning to imagine as their own.

In many ways, establishing a consistent presence of the Italian state in forgotten or resistant corners of the country was as much about symbolism as it was about governance. The postal system delivered letters, yes, but also the idea of Italy itself. (Along with the occasional confusion over which Giovanni the letter was actually meant for.) And it began working toward goals Italy is still grappling with today: making the country feel less fragmented and more equal across its many regions.

Employees at work in the Post Office's equipment room; Courtesy of Poste Italiane

As Italy Grew, So Did Poste

Over the years, Poste expanded its services to include telegrams, money orders, pensions, and savings bonds. It kept soldiers connected to their families during two World Wars. When bombs started dropping and bridges, roads and other critical infrastructure were damaged, postal workers provided a sense of normalcy by continuing to operate in a dangerous country.

During the Fascist era, the institution once loved by many Italians became an arm of the authoritarian state—a surveillance tool woven into daily life. Mail was routinely intercepted, read, and censored, or disappeared entirely, if its contents were seen as suspicious or contained criticism of the state. As a result, people learned to restrain themselves even in love letters.

Poste also played an active part in spreading Fascist propaganda, distributing state-sanctioned newspapers, pamphlets, and messaging that glorified Mussolini and reinforced the regime’s ideology. What was once an institution that brought people together was now being used to keep them in line, tightening the regime’s grip on people’s everyday lives.

But Facism ended and so did the great wars, and Poste helped rebuild Italy logistically and economically. Savings collected via postal savings passbooks (Libretti) and bonds (Buoni Fruttiferi Postali) were used to fund the construction and modernization of essential infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and public buildings including schools and hospitals.

By the 1990s, Poste Italiane had become a financial institution, a community touchpoint, and a symbol that the state is present for Italians. Private banks offered speedier and more efficient services. Digitalization made in-person experiences more costly and less relevant. But Poste endured—and more importantly, Poste adapted.

When the internet arrived, Poste launched wide ranging online services but never stopped its original offering: in-person, intimate, and analog counter services.

Inside the post office; Courtesy of Poste Italiane

The Modern Poste

Curious about how a 160-year-old institution stays relevant and vital, I turned to Poste Italiane for answers. Today, Poste is not only the country’s largest logistics network—it’s also a major financial services provider and a publicly listed company.

According to data shared with Italy Segreta by Poste Italiane, as of late 2024, there were 12,755 post offices across Italy which played a critical role in delivering 2.1 billion pieces of mail. Poste Italiane also employs 119,117 people. A significant number considering the country’s staggering 6.5% unemployment rate.

What makes Poste more than a logistics operation is its design. One official at Poste Italiane explained that in Italy, it’s often said every village can count on two things: the post office and the Carabinieri. We laughed over the phone, as he added that local communities often reach out to their mayors, asking for a Poste branch to be opened in their town.

As the officials explained, this physical and manual intimacy is a matter of business strategy. I am told by virtue of being a publicly listed company, Poste Italiane deeply cares about both business and performance. And their current leadership made a very intentional decision to keep the number of physical branches Poste has all throughout Italy, even as the rest of the world goes digital. When I ask why, their response is clear: Poste Italiane believes maintaining physical presence is a win-win. It’s good for business, it’s good for their shareholders, it’s good for Italy—and most importantly, it’s good for the communities they serve.

More Than Mail: Poste as Social Glue

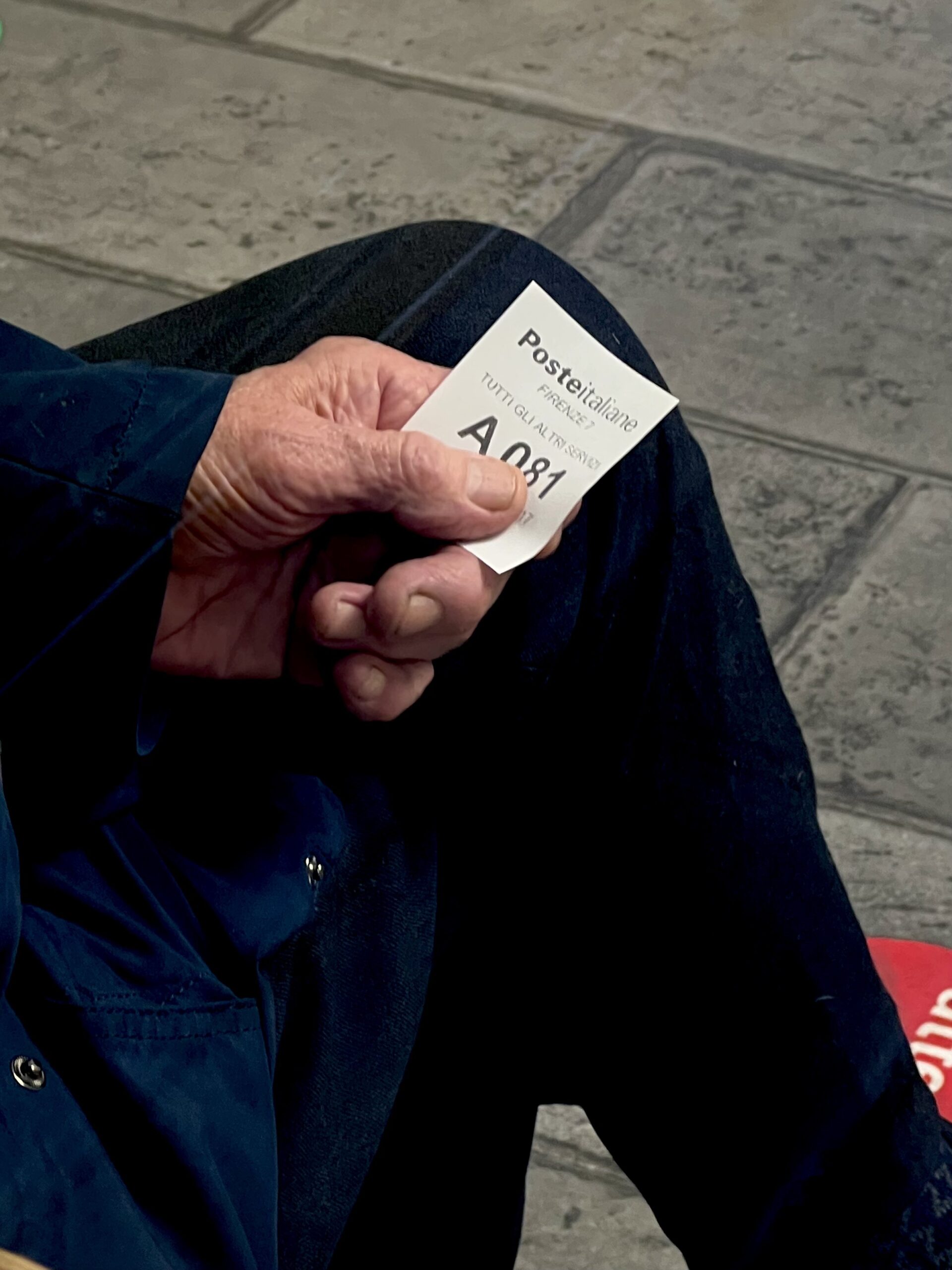

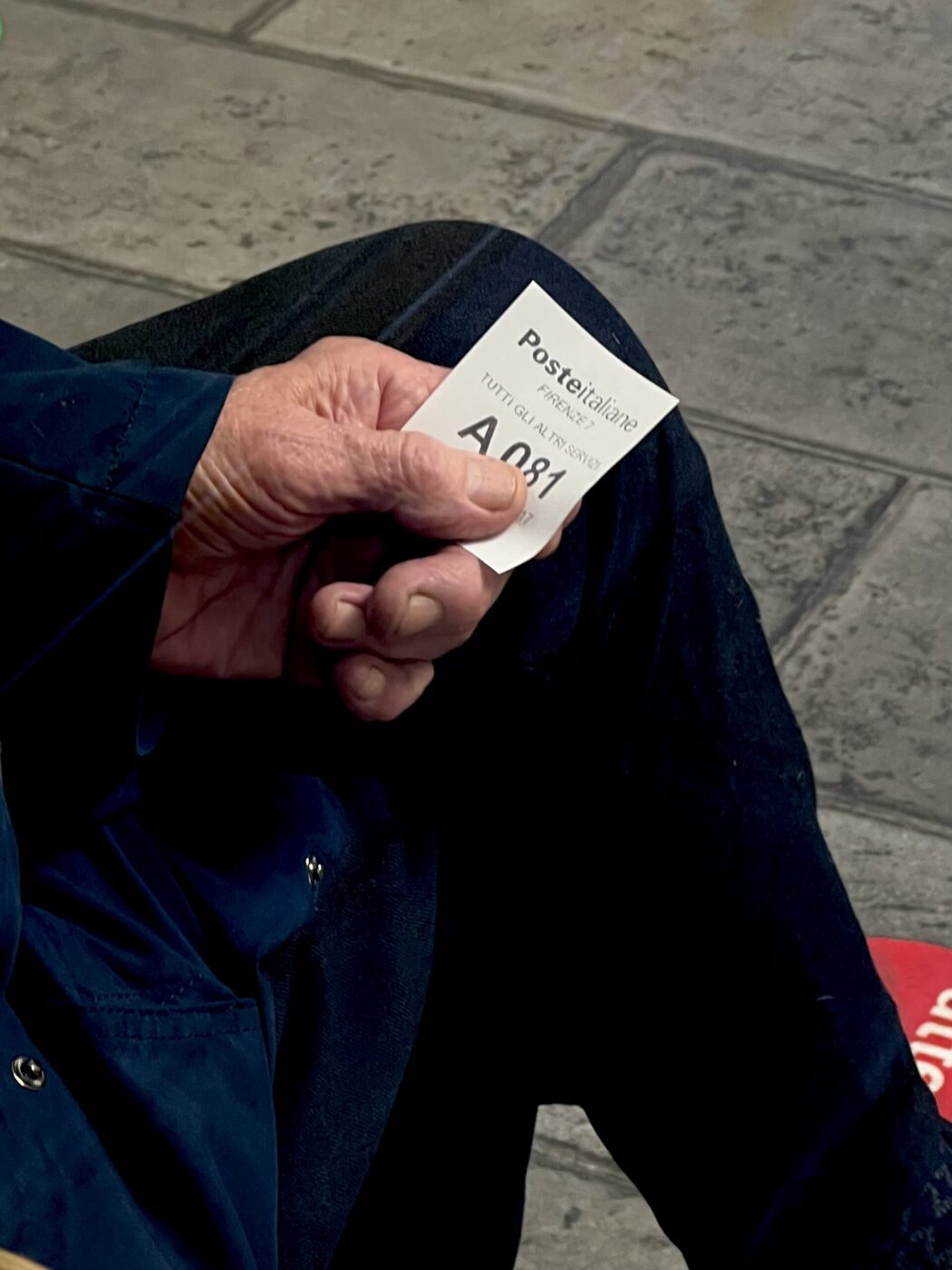

I witnessed Poste Italiane’s charm firsthand at the Piazza Bologna branch in Rome, where the warm, intimate atmosphere contrasted with the building’s brutalist grandeur. A small group had already gathered at the ticket machine, offering each other advice on which button to press while talking about the latest neighborhood news.

With help from a bystander, my husband and I pressed the recommended button, picked up our queue number, and started people-watching during our long wait. At one point, my husband nodded toward a woman in her forties. “She came to the post office to pay a bill she could have easily paid online,” he whispered. “For her, this is a social activity.”

And he was right. The woman greeted the clerk like an old friend. They chatted about how busy they are, complained about grocery prices, and traded jokes I only half-understood with my much challenged Italian.

To see if this phenomenon held outside the capital, I visited a smaller branch in Taranto, a sun-washed port city in Puglia. Gone were the marble columns and looming façades, but the spirit remained.

I spoke to a postal worker, asking her about the role this branch plays in the wider community. Cheerful in a summer dress and enjoying the air conditioning during a heatwave, she told me, “We have a lot of customers that come from remote villages. We’ve known them for a very very long time. They come here not only for our services but to hang out with us.” She added that their relationship is very affettuoso, especially with the older ones who prefer the in-person experience and can’t use many of the digital services.

When I approached a customer to verify these comments—an older woman from Taranto—she launched into an impassioned explanation: unable to use the Poste Italiane app, she had lost €1,000 her cousin had sent from the UK. She confirmed, without hesitation, that she needs in-person help and comes to the branch for exactly that reason—while adding that all this app business is “complete nonsense!”

Sure, you might lose a parcel or grow old waiting in line, but you’ll also overhear gossip, get life advice from a stranger, and maybe make a friend. At its core, Poste Italiane has managed to become one of Italy’s most dependable institutions. It’s warm, stubbornly analog, and still standing, even in an era of next-day delivery and vanishing human contact.

Whether at the grand branch in Piazza Bologna, the modest outpost in Taranto, or during my phone call with Poste officials, the focus on meaningful human connection—both as company strategy and as a reflection of the way business is done in Italy—was affirmed as vital. It’s most likely why the Poste Italiane persists not just as a logistical relic, but as the rare public space where Italians still show up, talk to each other, and press the wrong button on the ticket machine together.