Rural Salento, the southernmost part of Italy’s “heel” that is Puglia, is not where one expects to eat vegan food.

Agriturismo Piccapane sits on the long, typically flat Pugliese road between Galatina and Cutrofiano, about 45 minutes southwest of Lecce. As far as the eye can see, this is deep olive oil country: rows upon rows of olive trees just barely blow in the weak breeze of August, waiting patiently for the change in season that will mean their harvest can begin. The coastline is not far (though late summer’s dry air would have you think otherwise), neither of the Adriatic Sea nor the Gulf of Taranto, where Puglia’s coastal towns and larger cities seem to overflow with fish and seafood, whether at markets or on the seaside promenades where fishermen sell their fresh catches. When you drive down the road in either direction from Piccapane, either toward Lecce or the smaller Salentino towns, it’s impossible to miss the multiple caseifici (dairy producers) that display signs advertising their very own mozzarella di bufala, ricotta, and other fresh cheeses that they sell on-site to locals and road trippers alike.

Giuseppe Pellegrino, the owner of Agriturismo Piccapane, invokes an old Italian expression as he explains the inspiration behind his agriturismo’s name: “‘Piccapane e pica paternosci,’ goes the proverb,” he tells me—or, in modern Italian, poco pane e pochi padrenostri. Beyond the literal translation–“a little bread, a few prayers”–the proverbial connotation is to be satisfied and happy with what one has.

Pellegrino, who took over the land that is now Piccapane from his parents and grandparents, applied this philosophy and his commitment to sustainability to the agriturismo and its restaurant. The Biosteria Piccapane focuses on what its own land produces (vegetables, fruit, olive oil, legumes, and grains), making it not only kilometer-zero, but also completely vegan.

While veganism and vegan dining options have been on the rise here in recent years, as in the rest of the world, in Italy overall it is less evident in rural areas than in cities. But Piccapane and its Biosteria don’t exist merely to stand out as an exception to this general rule. Instead, as Pellegrino wants to correct the impression, the very nature and geography of Puglia–and the history of Pugliese cuisine as a whole–make them a solid ground for completely overturning it.

Agriturismo Piccapane

Plant-based Puglia: The unexpected roots

Vegan food might be a minority in Puglia, but it isn’t new. Yes, it’s true that Puglia and the Salento region are so known for their production and consumption of fresh cheeses that the category is given its own name—latticini–to distinguish them from aged cheeses, far lower on the Pugliese list of culinary delights. Mozzarella di bufala is sometimes as much of a draw for tourists as Lecce’s Baroque architecture or the trulli houses in the countryside, and eating along the Pugliese coast is practically synonymous with plates of bright pink shrimp and stuffed mussels. In reality, however, Pugliese cuisine has indisputable and yet almost imperceptible roots in vegetarian and even vegan food, far before either term existed.

“Until the 1950s, [about] 80% of the population in Puglia was vegan out of necessity,” Pellegrino explains, because the poorest Pugliesi simply couldn’t afford to eat meat. It was accessible only to the richer classes, even if seafood was a natural choice for those who lived close enough to the coast.

But both historically and today, the quality and abundance of Puglia’s year-round produce—as well as its olive oil and durum wheat production—have made it easy for the region’s cuisine to rely on little else from outside its borders and to revolve around naturally plant-based ingredients. As in much of the South, olive oil is always the preferred cooking fat to butter, and pasta, even fresh, is vegan from the get-go in these parts. Orecchiette, Puglia’s ubiquitous pasta shape, is just one example of how durum wheat semolina, the dominant flour throughout the south, need only be mixed with water to make fresh pasta, as opposed to the egg-based doughs of the north.

“Pugliese cuisine is really primarily vegetarian [and] vegan, because our land offers so many different types of vegetables and fruit that have always made up our most classic, typical dishes,” says Rosella Lafronza, who grew up in Puglia and now lives further north in Modena, Emilia-Romagna. Lafronza says that it’s “easy to satisfy vegan diners” at her own Pugliese restaurant, Pugliami per la Gola in Modena, Emilia-Romagna. And when Lafronza, a vegetarian herself, visits her family in Puglia? “Even though my parents eat meat, they really don’t eat it super often—both out of habit and because for many [Pugliese] recipes it’s not necessary.”

Local, zero-kilometer food vs. the threat of modern food production

Pino Ferraris, the chef at Piccapane, emphasizes the same about local specialties. “Many recipes from the Salento rural tradition are naturally vegan—orecchiette alle cime di rapa [orecchiette pasta with broccoli rabe], fave e cicoria [puréed fava beans with sautéed chicory], pasta e ceci [pasta with chickpeas], and even certain desserts that were made with just almonds and sugar to create delicious and completely vegan cookies,” Ferraris says. He is referring to the fact that almonds appear in many traditional recipes, thanks to Puglia’s high cultivation of almond trees, whose pink blossoms line countryside roads in the spring.

And yet, Puglia today isn’t immune to global food production and the industrialization of agriculture—nor indeed is any Italian region in the 21st century, contrary to the popular belief that makes Italy a bucolic ideal safe from the waves of change—particularly when it comes to meat. Even horse meat, historically eaten in Puglia since rural farmers sourced it from their own animals, now comes to the region mostly from outside Italy simply to meet the continuing demand, despite the fact that its consumption reflects an outdated farming practice. And, even though Puglia’s terrain has always been most suited to raising goat and sheep rather than cattle and pigs (traditional meat dishes primarily feature goat, mutton, or lamb), Pellegrino explains why modern Puglia’s meat consumption is often the root of a larger problem: “Just like much of the rest of the world, the meat that we consume the most in Puglia is beef and pork, which are not local and come from industrial farming. And everything that comes from industrial farming is unsustainable.”

Of course, many agriturismi and other small-production farms are dedicated to preaching this philosophy, encouraging communities to eat not only locally but from non-industrial sources, and thus follow kilometer-zero practices (a term that, naturally, only came into existence in the last few decades as a response to the increasing threat of mass food production). In the part of Salento that Piccapane occupies, one could easily source mozzarella, ricotta, and other latticini from the small dairy producers down the road and technically maintain the kilometer-zero definition. But Pellegrino has taken the Biosteria Piccapane one step further in the approach to veganism and is committed to creating a more radical version of the overarching philosophy.

A new kind of osteria: sustainability and the power of open-mindedness

“The idea for the Biosteria was [not only] to give an outlet and visibility to organic, local food and small-production farms… The intention is to show people that you can eat healthily and flavorfully without animal proteins, and that this way of eating is possible even in Puglia.” (The one exception, Pellegrino concedes, is on the occasional pizza night, when the Biosteria puts its outdoor wood-fired brick oven to good use and tops several different pizzas with, yes, mozzarella and sometimes ricotta from one of Piccapane’s neighbors, a small dairy with only 10 cows. Vegan pizzas, of course, coexist on the evening’s menu.)

When I first ask Pellegrino how long he’s been vegan, he is quick to correct me that he isn’t one himself—he’s almost completely vegetarian and simply makes sure that the animal products he does eat (fish perhaps once a week, meat maybe once a month, Pugliese cheese occasionally) come from only small farms, and when possible from neighbors where he knows “the wellbeing of the animal is a given.” But he wanted to make the Biosteria vegan as a vehicle for broadening people’s perspectives about an even more sustainable way of eating, and to make veganism seem less alien–and even enjoyable once in a while.

Since the Biosteria’s opening in 2012, the majority of diners at Piccapane have been non-vegans–mostly locals from Lecce and the surrounding province who are surely accustomed to more fish- and dairy-filled meals. From the start, the local Pugliesi were curious to try the Biosteria and arrived in droves, “because we were a completely new thing” for the area, as Pellegrino puts it. (As an agriturismo, Piccapane offers a few guest rooms for people to stay in, but the 30-seat restaurant is open to the public.)

“We can still count on our small and close-knit group of locals who come back regularly, and on a steady influx of tourists during the summer season,” Pellegrino says–though it would be nice if tourists came more in the shoulder-season months, he says, from April to June and September through October, when temperatures are still mostly summer-like and the region is no less enticing. It’s worth noting that planning trips in the shoulder-season or off-season is significantly helpful not only for the hospitality industry, but also to the larger movement for more sustainable travel, as long as Italy and especially regions like Puglia continue to experience mass crowds.

In any case, given that the clientele continues to be mostly omnivore, it seems Pellegrino is succeeding in his mission to make vegan dining enjoyable even for people who aren’t 100% vegan 100% of the time.

Accidentally vegan?

“I think even plenty of Pugliesi themselves do not realize when the thing they’re eating is vegan,” Lafronza says, so entrenched in the cuisine are those already naturally vegan dishes.

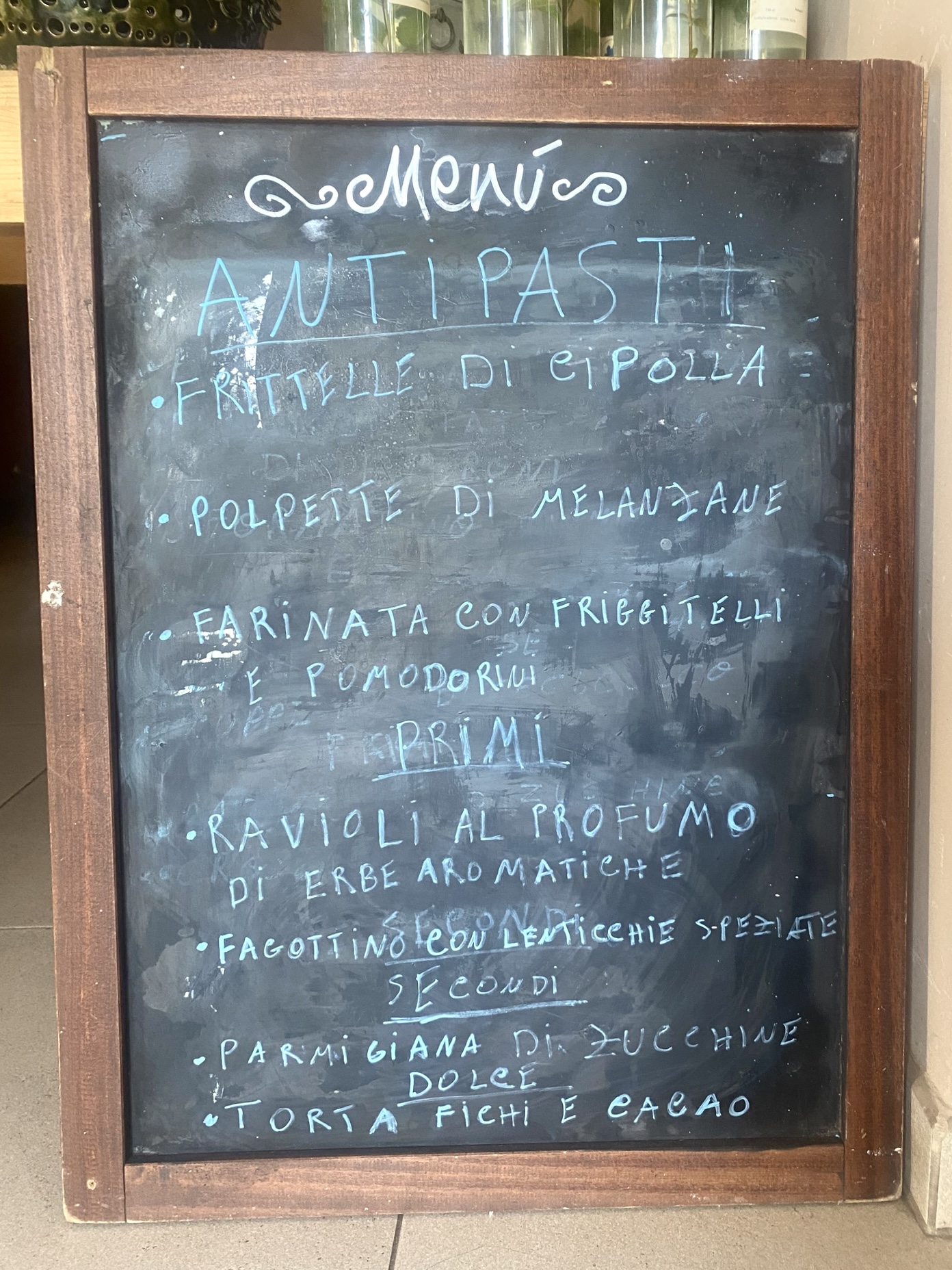

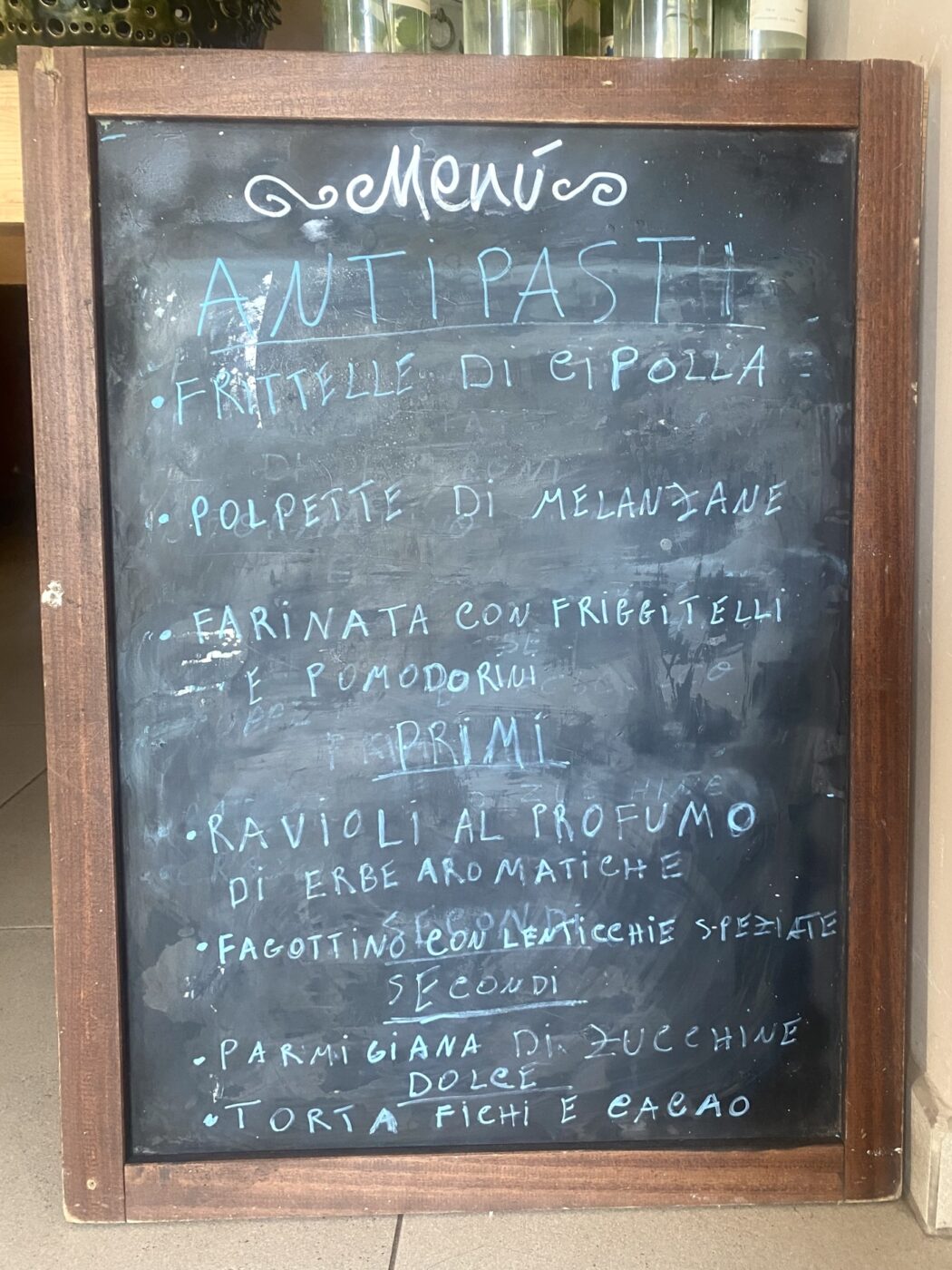

At Piccapane, even though the concept is of course advertised as vegan, the food does not feel wanting; the menu changes almost daily based on what’s been harvested from the orto, and given the typically Pugliese quality of these ingredients, it doesn’t take much to let them shine. Plates of various antipasti are no-brainer outlets for vegetables cooked simply and purely–summer is vibrant with zucchini a scapece (zucchini with vinegar and mint), baked eggplant polpette, and squares of grilled polenta with onion compote or sautéed swiss chard and tomatoes; in winter, it might be thinly sliced beet carpaccio with cashew dressing, and polpette with pumpkin. (Mercifully, the light-as-air onion fritters make multi-seasonal appearances.)

The tendency of the Biosteria to serve all three of the daily vegetables together as one antipasto for each diner is an intelligent way to set the tone for the evening—you will eat well, and not by any means too little nor austerely. But the simplicity of the setting does help establish another positive factor of vegan dining in an agriturismo context—the four-course menu costs just 30 euros per person, excluding beverages. The wine on offer is always organic, low-intervention wine from small producers nearby or those whom Pellegrino meets throughout the country when exhibiting products at agricultural fairs.

Primi and secondi might be eggplant and zucchini parmigiana-style baked casseroles; chickpea flour farinata (chickpea flatbread) or crespelle stuffed with slow-cooked vegetables; or orecchiette with broccoli and pomodori secchi, the garden’s tomatoes that were dried in the open air under the hot August sun and stored away for winter. At the turn of September, when the first pumpkins arrive in the kitchen from Piccapane’s garden, they’re used for pasta alla zucca with sage and a vegan cream sauce instead of butter—one of few instances when the restaurant will use vegan versions of common pantry ingredients.

Such substitutes are kept to a minimum, and Piccapane purchases them exclusively from small producers or organic wholesalers. This is more pertinent to baked goods and other sweets when the kitchen wants to experiment beyond almond cookies and naturally vegan recipes, since “making a dessert without butter, milks, or eggs is not a simple thing,” chef Ferraris says. “You have to use substitutes like non-dairy milk, vegetable oil, flaxseed meal… Various starches are also important for vegan cooking, for example cornstarch or potato starch, which give a creamy consistency to sauces and pastry creams for different desserts.”

Before such considerations, Piccapane’s dolci are nonetheless blessed with the luxury of perfectly ripe fruit picked from the fields that morning. Figs and apricots make tarts, cakes, and dessert compotes in the summer. Oranges and citrus create bright marmalade crostate in the winter–a period when it’s also easy enough to make vegan desserts that aren’t fruit-based, like Italian hot chocolate with pan dolce to dip it in, or chiacchiere, the fried sugared dough that reigns during Carnevale season.

But for the most part, the cooking style at Piccapane acknowledges and honors Pugliese quality and Italian culinary simplicity, even with a creative force of a chef who has worked for many years internationally.

“To me, vegan cooking doesn’t mean just substituting vegan ingredients into classic recipes,” Ferraris says. “Vegan food is a return to the origins of true, old-fashioned home-cooking, the cuisine of farmers, when people cooked only with what the land gave them.”

La Nostra Terra: Future food for thought

The proverb that Pellegrino referred to contains another component, in some iterations, after its instruction to be satisfied with the little bread that life offers you–“non abbandonare la tua terra” (“do not abandon your land”). Experiencing life in Puglia, and Piccapane as a microcosm of the local culture, does make it tempting to not ever leave this corner of the world, even if it’s not your own. But not abandoning a place also means taking care of it, and you don’t have to be in Puglia to appreciate that we need to protect our planet’s environmental future, nor do you have to be vegan 100% of the time to help in this effort. But eating locally, organically, and intelligently–and understanding the intentions behind veganism and vegetarianism, besides perhaps eating this way once in a while–makes vast progress.

––––

You can purchase Piccapane’s ingredients and provisions (olives and olive oil, jams and compotes, sauces and spreads, sun-dried tomatoes and figs, flours and pasta made from their grains, dried legumes, olive-oil packed vegetables, and more) from their online shop (biosteria.piccapane.it), which ships throughout Italy as well as internationally.