Pellestrina is a slender, elongated strip of land–to be exact, 11 kilometers long–placed between the Venetian Lagoon and the Adriatic Sea. Its width varies from a minimum of 23 m to a maximum of 1.2 km, which is also the distance between salty and brackish water. On the lagoon side, a necklace of small colorful houses–boats docked in front–each painted in a bright color, distinct from the ones next to it. For some reason, the result is not the typical Murano look you’ve seen on Instagram. Simplicity is at the core of Pellestrina: it’s a place built simply to be inhabited. In the middle of the island, separating lagoon from sea, is a long wall known as “la diga”. On the other side, the sea side, a sandy, wild beach reaches from one tip to the other. The only structures providing shade are capanni, little sheds built by islanders with whatever the sea has brought ashore during the winter. Other than a line of shrubs lining the wall, there is little to no vegetation. The summer is hot and moist, the air heavy; nights are blessed by a soft breeze, and islanders meet daily on the lagoon bank. Someone might feel lucky and try to fish; most spend the time slowly chatting about the slowness of the days.

As a kid, it was the island of parent-imposed, endless Sundays strolls I much complained about. Either by bike or on foot, there seemed to be no stopping. It seemed so pointless to walk aimlessly for hours just to reach a bench at the opposite end, eat a sandwich, and go back again. My loud remonstrations were always met with the same cryptic, aphoristic sentence: “On an island, you go to be isolated.”

Years went by, and my family, which lives in the region, finally decided to buy a small house, roughly mid-island, facing the lagoon. “A refuge,” they said. What they needed to seek refuge from, eleven-year-old me was not sure. Come winter, summer, spring, and fall, they left on a Friday to come back on Monday–revived and relieved it seemed. Hard to understand how a place that looked so boring could produce such an effect. But after all, as José Saramago once wrote, “Every island is unknown until you set foot on it.”

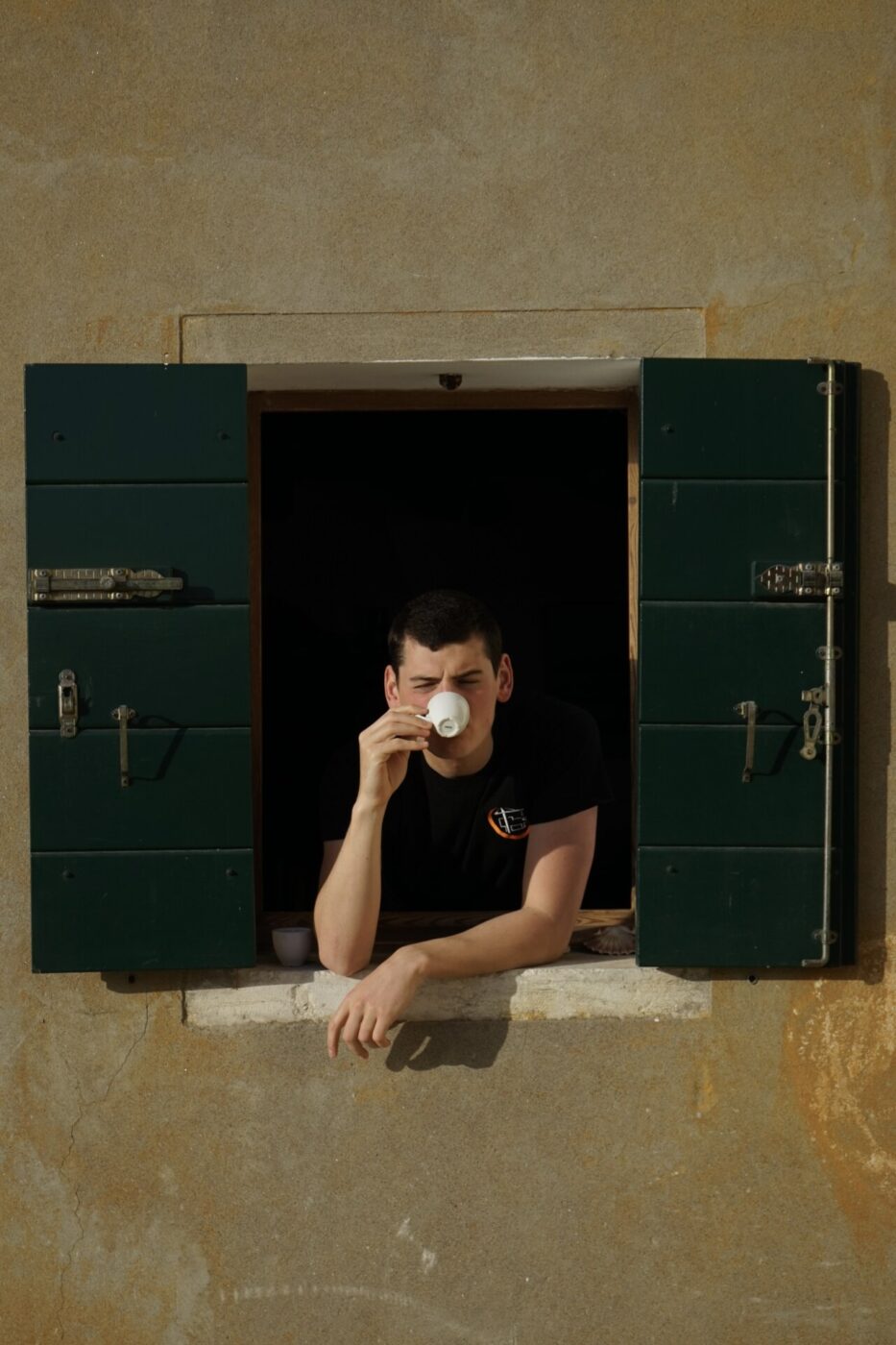

More years went by, and I started to visit every now and then. There was something raw and genuine in the place and its people that I was not quite able to grasp. I would carry a backpack full of books, find a corner, and get lost in imaginary worlds. And time started acquiring more relevance; its measurement was something else entirely on the island. With little to nothing planned, little to nothing to do–with just one bar/pizza place, a minimarket, and a newsstand to choose from for entertainment–the days had to be wholly invented. They were blank pieces of paper. The time organization I was used to suddenly was worth nothing, and this compulsory restraint from “productive” activities generated a curiosity and a desire to know more–which ended up as a desire to know everything. Every time I went to Pellestrina, I wanted to stay longer, and I started observing, asking questions.

A FISHERMAN’S ISLAND

The island was first colonized–like all Venetian islands–after the Barbarian invasions of the 6th century, by the local population running from the mainland. Its main commercial activity has since been fishing. Pellestrina really has both the history and the soul of a fisherman’s island. It is the place of their knowledge, that kind of knowledge that can only be defined as ancient and empirical and can only derive from long-standing traditions. There is no such thing as chance, coincidence, or accident on the island. Take the colors of the houses. Tourists, who reach the island in crowds during the summer months, take thousands of pictures of the constructions, all painted and very Instagrammable. But their social media draw is not the reason behind the color choices; practicality is. Each house was painted to look different so that fishermen could distinguish them in the early morning fog, arriving home safely and quickly after the night spent fishing and providing for their families. Chimneys also look peculiar, with a larger than usual structure on top. Usually built in metal, and often decorated with either paint or majolica, they look like iron boxes. Again, not a mere choice of style: these chimneys’ size protect what is often still the only source of domestic heat–the fireplace–from the strong winds that seasonally blow on the island.

The island is also full of capi saldi: rusty metal cylinders, about five centimeters in diameter, plugged into walls, historically used for geographical orientation. These days, they are more points of reference that preserve our sense of place.

(To try the best of the fishermen’s catch, head to seafood joint Da Nane. Order all the coastal classics–gnocchetti di patate agli scampi, polipetti caldi, vongole–on a terrace overlooking the water.)

THE UNDERBELLY OF “PEACEFULNESS”

During the summer–increasingly so in the past few years–Pellestrina is stormed by tourists looking for the island’s commodified version of peace. The pandemic, with the lack of flights and inability to reach holiday destinations further away, scaled up the process. By contrast, in the winter and the colder months, the island is emptied, left to its 4,000 residents. Boredom takes over. A life marked by this contrast can be especially critical for young people, and most of them decide to leave at a very young age. Those who chose to stay have to confront island life’s differences from that on the mainland or in Venice: there are no high schools in Pellestrina, and, from the age of 14, students must get to Venice every morning to carry on studying. After that, it is only a matter of choice. In a recently published memoir, Battaglie di Neve: Memories of an Addict (2022), Pellestrina native Emanuele Ballarin tells the all-too-common story of many young people raised in the Lagoon: the harsh contrast between the summer and winter life, between the constant movement of the one and the seemingly-endless quietness of the other, often leads the young to seek other forms of entertainment… and to find it in drug use. It isn’t infrequent, Ballarin explains, for local kids to develop addictions from a very early age.

The constantly rising rate of unemployment–these days, around 40%–certainly doesn’t help. The only company left today that works year-round, unbothered by the floating rhythms of tourism, is a boatyard.

MOSE: PELLESTRINA BEARS THE BRUNT FOR VENICE

The fishing tradition of the island came to an abrupt halt with the construction of the MOSE project, which started in 2003 and is supposed to finish next September–gigantic dams placed in all the bocche di porto of the Venetian lagoon, thought to mitigate the devastating effects of Acqua Alta on the city of Venice. Fishermen were encouraged to scrap their boats and cease all activities, though no alternative sources of employment were offered to them. Further, MOSE risks jeopardizing local biodiversity. Fish is now harder and harder to source locally, as the interchange of water between the sea and the lagoon, essential for preserving the habitat, is hindered. And it’s not only fish that risks being lost in the process, but local culinary tradition too.

Pellestrina, especially, is at great risk as its location forces the island to act almost like a shield for Venice. The Acqua Granda of 2019, when the water reached almost two meters in height, was a perfect example of this forced vulnerability. As part of the MOSE project, a one-meter-high wall was built on the lagoon side of Pellestrina; islanders notified the crew from the beginning that if the water got over the wall, it would be unable to flow back into the lagoon. Exactly this happened, and the island was underwater for more than 24 hours. “We are left on the seabed like clams,” locals said. An article from La Repubblica called it “the shame of Venice.”

Again, engineer expertise rarely takes notice of local knowledge–which could have, in this case, prevented 100,000 euros of damage. But the question of Venice’s fragility is a delicate one: some, like renowned Professor Luca Palmeri, claim there must be a choice between saving Venice and the other neighboring islands. Others, like Professor Luca Barausse, bravely embark on local, nature-based environmental conservation projects to seek alternative routes that might save both. Starting in 2013, he launched the project LIFE VIMINE, involving local fishermen and their inherited knowledge to reduce erosion of the Barens, floating islands of vegetation that are considered the lagoon’s lungs. This union of local knowledge and innovation might just be the key to imagining a different future to this seemingly inevitable ending.

Places like Pellestrina–especially as it lives in the glorious, but quite frankly cumbersome, shadow of an immense cultural heritage like Venice–must be protected and looked after, with care. A true, proper, precious, and rare human side of life is tightly linked to their existence. We have a duty towards them. One of respect and careful observation. Places like these could be the last strongholds for the possibility of building something different.

Someone I love recently sent me an article by Giovanni Boine, an Italian writer of the early 1900s. In the piece, Boine questions what being Italian means (if it does indeed mean anything)–or rather he underlines the lack of analysis on the topic by those who blindly incite an empty nationalism. Of course, it is hard to define what principles, feelings, or values are underlying a nation, especially one as pluralistic as Italy. Yet, in places like Pellestrina, you can get a vague, hard-to-grasp but deeply rooted feeling of how Italy breathes, of Italian life lived through the simple things, where the deepest truths are often to be found. What I know for a fact is–just like the first population running from the Barbarians, just like my parents running from the barbaric menaces of modern life–Pellestrina has become a shelter for me, a source of teachings and a way to engage with myself, and life, differently. A space to be isolated, as I now understand, in the best way possible. On the ferry to the mainland, I promise myself that I’ll try to build the imaginary worlds I used to read about as a kid. And so here I go back. Once and again, revived and relieved.