By the time my husband rolled me into Milan’s Buzzi Hospital in the early hours of Christmas morning a few years ago, our ultimate gift was already two weeks late. Of the many details I remember from the 20-plus hours of labor, one stands out: a little red box on the lunch tray, cradling a buttery treat that offered a fleeting flicker of festivity between increasingly insistent contractions. It was a mini panettone—soft, airy, and unmistakably Christmassy.

All panettone shares the same sweet, brioche-like soul: moist yet featherlight, cylindrical in form, and always presented whole before being cut into wedges. I hardly missed the uniquely Milanese tradition of pairing it with a dollop of Marsala-spiked mascarpone or a glass of dry spumante (though I certainly wouldn’t have refused it). The hospital attendants, decked out in elf hats, grimaced at my one-too-many requests. Night fell, but my baby didn’t. That tiny, personal panettone would become my last moment of calm before an emergency C-section. And though a visitor smuggled in a few Marchesi pastries the next morning, nothing would compare to the memory of my sweet little panettone.

Throughout my childhood in suburban New York, Zia Maria—a close family friend—was our gateway to all things Italian. Thanks to her, our Christmas meal always ended with a proper panettone from Italy. The domed cake-bread hybrid arrived in an elegant, hat-like box. As Zia Maria lifted the knife, we’d hold our breath in anticipation of its collapse, then exhale in relief as it held its form, stylishly, almost imperceptibly bowing.

My brother and I would pick out the raisins and candied fruit, tearing off doughy sheaths and lowering them into our mouths. “Children are expected to pick out the raisins and canditi—they make panettone more of an adult dessert,” explains Italian-born, San Francisco-based chef (and friend) Viola Buitoni, over the phone. “My mother used to say she was fat because she got all the leftovers from her five children.”

Panettone has by now claimed a place on Christmas tables around the world, but it’s originally from my adoptive Milan. As with many beloved foods, its origin story depends on who you ask.

One tale stars Ughetto, a noble falcon trainer who fell in love with Adalgisa, the daughter of a struggling baker. Disguising himself as a peasant, he offered to help in the bakery, secretly selling his birds to buy sugar, eggs, butter—rare luxuries in 15th-century Milan. He enriched her dough, added raisins and canditi, and saved the bakery (and won the girl). Fittingly, ughett means “raisin” in Milanese dialect.

Another version credits Toni, a scullery cook in the kitchen of Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan. When the official dessert for the Duke’s lavish Christmas banquet was burned, Toni offered up his own sourdough starter, transforming it into a rich, golden loaf filled with raisins and citrus peel. The Duke was so pleased he named it pan de Toni—Toni’s bread.

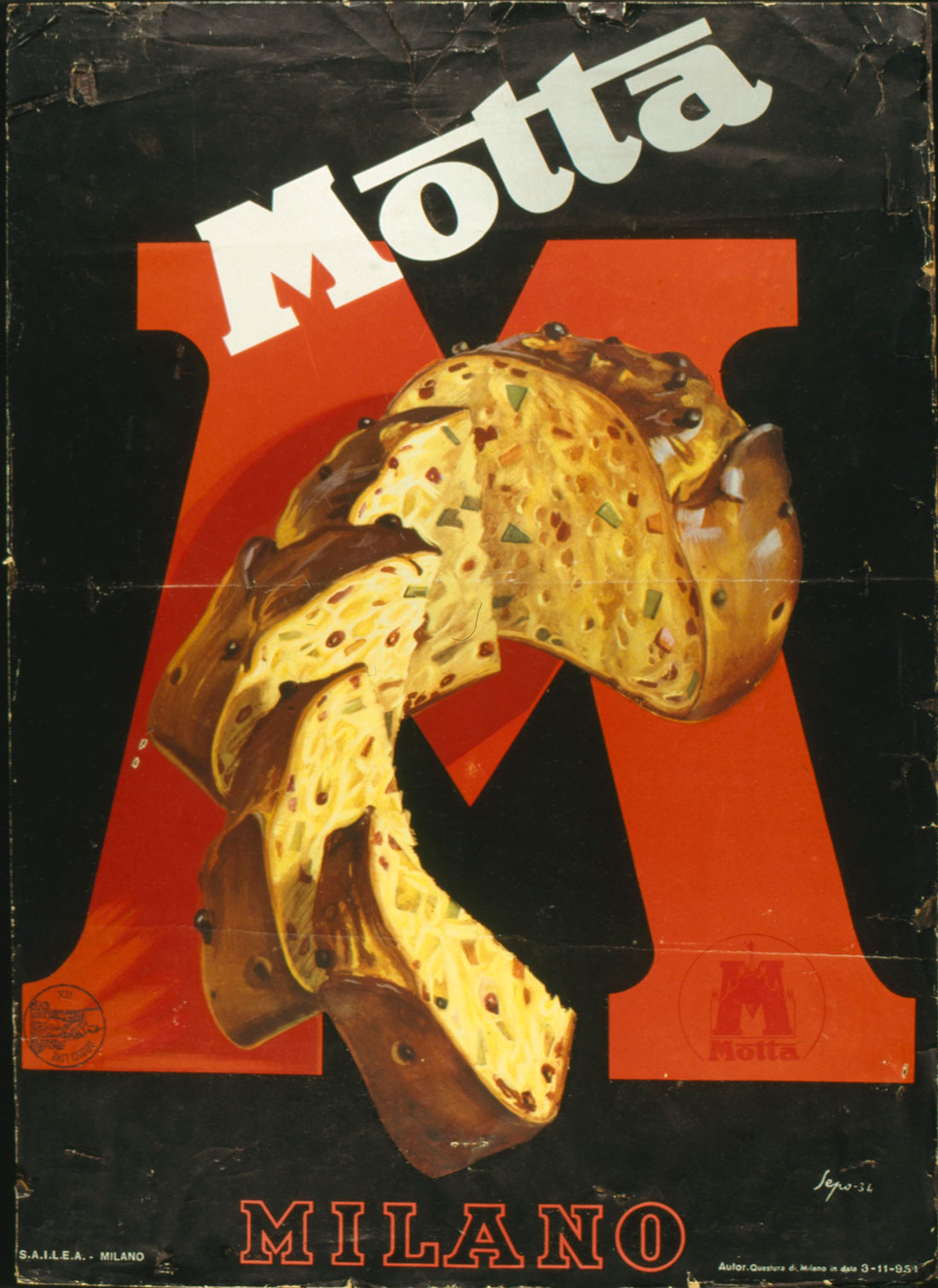

Whatever the truth, Milan’s Biblioteca Ambrosiana jealously guards a manuscript from the 1470s that contains the earliest known mention of the celebratory sweet. The domed shape has always been its defining feature, but panettone remained squat, bread-like, and mostly local until the 1920s, when the Motta family introduced a powerful leavening method fit for mass production, ushering in the now-iconic alto (tall) form.

Stanislao Porzio, food scholar and author of Il Panettone: Storia, Leggende, Segreti e Fortune di un Protagonista del Natale (2007)—the most comprehensive Italian book on the subject—writes that panettone entered mass production when Motta opened a factory on Milan’s Viale Corsica, featuring a then-revolutionary thirty-meter oven. Over the years, Motta helped shape the industrial market, yet their mother yeast still anchors the recipe, even as production stretches to South America and beyond.

Since Motta’s rise, the toque-shaped sweet became such a Milanese symbol that in the 1980s, designer Enzo Mari modeled the city’s concrete traffic bollards—those short posts that keep cars off sidewalks—on its form.

A handful of Milanese bakeries serve panettone year-round for breakfast, but it’s during the winter holidays that it becomes ubiquitous across Italy—and a real obsession for the city’s locals. Starting in November, Milan hosts a few large panettone festivals—competitions in name, marketplaces in spirit—that give small bakeries a chance to tap into the city’s appetite for new takes on the classic sweet.

Once, panettone-obsessed writer and Italy Segreta contributor Margo Schächter led me through I Maestri del Panettone, a two-day pop-up where 20 pastry chefs showcased over 150 varieties. After a line that snaked around the block, visitors entered to find a Last Supper-style table of judges tasting slice after slice before a captive audience. Crowds swarmed the winners’ stands, eager to snag a finalist. By day’s end, over 15,000 loaves had been sold.

Porzio took things further thirteen years ago by founding Re Panettone (King Panettone)—a fair where all participating pasticcerias must guarantee their products are free of mono- and diglycerides, common industrial additives used to prolong shelf life. The festival honors panettone made according to Italy’s official decree: naturally fermented starter, at least 16% butter, fresh eggs, and no additives or preservatives. Brewer’s yeast, starches, vegetable fats (except cocoa butter), whey, soy lecithin, dyes, and preservatives are all strictly banned.

Porzio is also campaigning to have panettone-making added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list, alongside Neapolitan pizza (initiated in 2017) and the Mediterranean Diet (2013). His mission is to preserve the artisan’s role and uphold the purity, ritual, and rules that, in the words of master baker Nicola Olivieri, separate “the real from the fake.”

Traditional panettone classico Milanese is enriched with plump raisins and canditi—orange, lemon peel, and Sicilian citron, all candied—the purist’s preference. Things began to shift in the ’70s, when chocolate panettone gained popularity. Buitoni recalls the brouhaha that greeted what now feels like a quaint, widely accepted variation. It still takes real pastry pedigree to tamper with tradition, but a few young, forward-thinking bakers are experimenting with bold fermentations and flavors like ginger, black tea, and pistachio. Demand is growing for those dotted with dried figs and sour cherries, enriched with moscato, filled with gianduja, or infused with saffron. A successful pairing can create the right buzz, but only fermentation finesse earns a panettone its place among the truly exceptional.

If you’re not Milanese, you might have a more flexible relationship with panettone. According to Schächter, Southern Italians prefer theirs sweeter and fluffier, often opting for the shorter (basso) version—typically paler from baking at lower temperatures. Buitoni, who grew up in Umbria, remembers both styles from childhood: the artigianale alto arrived with her zia from Milan, while the basso, which she knew as Piedmontese, was prized by kids for its sugary, hazelnut-studded glaze—reminiscent of Dutch crunch.

As panettone options multiply like Pantone swatches in Italy’s pastry shops and supermarkets, Italians tend to group them into three categories—industriale, semi-artigianale, and artigianale (a taxonomy that often mirrors their price tags).

For much of the late 20th century, Nestlé effectively cornered the industrial panettone market, holding ownership or controlling stakes in Motta, Alemagna, and Perugina—three of the largest producers. Not coincidentally, this was also the era when panettone shifted from a seasonal specialty to a household staple. Even though, in 2009, the Verona-based Bauli brought Motta and Alemagna back to Italian ownership, little has changed on the supermarket shelf. Mass-produced versions remain largely indistinguishable, with price as the main differentiator. In fact, it’s common knowledge that supermarket panettone is often sold below cost, at €5 to €10, to lure in holiday shoppers. Thanks to preservatives, an industrial loaf can last well over six months.

Semi-artisanal panettone comes from medium-sized, family-owned producers who specialize in holiday sweets. They use high-quality ingredients but also have the technology to produce at a scale that meets the demands of stores like Eataly. A careful eye for packaging design typically distinguishes panettone in this category: these are coquettishly wrapped in ornate paper with intricate illustrations, glittering ribbons, or tucked into keepsake tins. Prices for semi-artisanal panettone range from €15 to €25, and most come with a best-by date no longer than three months.

Panettone artigianale from a local baker starts at €20 and can climb to €40 (or more) when made by one of Milan’s legendary pastry shops or Italy’s revered master bakers. You’re paying for more than impeccable texture and flavor—you’re supporting the dedication it takes to tame the unpredictability of fermentation over several days, and rewarding the passion of an artisan who’s toiled in the kitchen so you don’t have to.

These masterpieces, when not wrapped to order, are simply and stylishly clad—they don’t need designer clothing to command attention. No panettone artigianale worthy of the name lasts more than a month.

Fashion houses like Armani, Gucci, and Dolce & Gabbana have also joined the trend, offering signature panettone in branded tins—a pezzo forte for fashion lovers and far more affordable than a handbag.

One of Italy’s rising artisanal stars is the aforementioned Nicola Olivieri, a sixth-generation baker from Veneto’s Arzignano. After a pastry stage in Australia, he returned home to transform the family business into Olivieri 1882—a modern pasticceria housed in a repurposed warehouse that feels more Brooklyn than Venice. The all-day café is, in Olivieri’s words, “a sort of piazza where locals can meet and drink high-quality coffee and pastries.”

Olivieri’s work—which includes standout flavors like apricot and salted caramel, triple chocolate, and the distinctive Balsamic Vinegar of Modena panettone (as well as superlative pandoro)—is making waves across Italy’s pastry scene, rivaling the dernier cri spots of Milan and Rome. Even his business model is a break from tradition: rather than rely on a distant distributor, he now sells his panettone online, shipping it fresh—direct from Arzignano to the lucky recipient.

Nonno Bianco Olivieri

Buitoni remembers how hard it was to find panettone when she first moved to New York in the ’80s. She’d brave the crowds at Balducci’s in the East Village just to score a Perugina—commercial, overpriced, and one of the only options available. Today, panettone is as common on American shelves as peanut butter and as expected on holiday tables as fruitcake. But while all panettone made in Italy—even the cheapest industriale—must meet the standards of the ministerial decree, those rules are often bent or ignored once production shifts abroad.

Most Americans at Christmastime are eating “an industrial product packed with preservatives and low-quality ingredients,” says baker Olivieri. “It’s made in July or August, exported early, and left sitting on shelves for weeks before Christmas.”

But the trend is slowly shifting. These days, panettone semi-artigianale is available at better stores and through online retailers. And—albeit gradually—artigianale is making its way to the increasingly discerning palates of Americans in urban centers.

At Buitoni’s shop, Buitoni & Garretti—a fine Italian foods store she co-owned with Milanese catering partner Yolanda Garretti from 1999 to 2001—they splurged to have panettone artigianale shipped from the famed Gattullo pastry shop in Milan. Hoping just to cover shipping costs, they brought in 20 for their most particular clients. Even at $40 for a small and $65 for a large, they sold out in two days. By the following year, customers were reserving their holiday panettone artigianale as early as September.

Shortly after, Gustiamo in the Bronx began importing panettone artigianale from Luigi Biasetto—a Belgian-born, award-winning pastry master of Venetian descent whose name is spoken with reverence by those in the know. Even at $60 plus tax and shipping, demand quickly quadrupled their usual sales.

Jim Lahey—the New Yorker behind Sullivan Street Bakery, best known for his focaccia and no-knead bread recipe—found similar success. About five years ago, he began making small batches of panettone each Christmas—once so limited you had to reserve months in advance. Today, his loaves are available nationwide via Goldbelly.

From Arzignano to the Bronx to your doorstep, panettone has become a global pursuit—with loyalists, skeptics, and obsessive bakers all in the mix. But whichever panettone suits your taste and budget, there is one rule you need to observe: do not finish it in one sitting. Leave at least a wedge to toast for morning-after-Christmas breakfast. It also makes a killer French toast.

To get your panettone on this Christmas, here’s a short guide.

Artigianale:

Pasticceria Biasetto (Padova, Veneto) – Via Bronx, New York’s Gustiamo

Olivieri 1882 (Arzignano, Veneto) – Direct from website

From Roy (San Francisco, CA) – Direct from website

Sullivan Street Bakery (New York, NY) – Via Goldbelly

Marchesi 1824 (Milan) – This Milan institution has three stores in the city plus one in London, and you can order their superb panettone online.

Semi-artigianale:

Loison (Verona) – This family-run, high-end baked goods producer has Christmas goods available online from San Francisco importer Howard Case.

Albertengo (Cuneo) – This bakery has been making Piedmontese panettone for over a century. Find their delights on iGourmet,

If you happen to be in Milano:

These artisans make a few different types of panettone on a limited run so it’s best to order ahead.

LePolveri (Milan) – This micro panificio always has a line out the door and sells panettone by reservation only.

Panificio Davide Longoni (Milan) – A destination for bread in Milan, as Longoni is known for experimenting with non-traditional flours, ancient ancient grains and fermentations.

Pasticceria Polenghi (Milan) – This is a family-business, run by Angelo—in his 70s—and founded by his mother in 1945. He only makes only 400 classico Milanese, and still uses the cooling baskets his family passed down to him. Most of his customers know him by name.