The dormant vines are naked and spindly, taking on a spooky, Tim Burton-esque quality in the fog as we wind our way through the Barolo-producing land known as Le Langhe. Hairpin turn after hairpin turn takes us to Roddino, home to restaurant Osteria da Gemma and, it seems, not a soul.

Marina and I are here to meet the eponymous 70-something Gemma Boeri, a celebrity among the culinary cognoscenti. I first heard her name on my second night in Piedmont, a fresh arrival for a master’s at the nearby University of Gastronomic Sciences (UNISG). Waxing poetic on her tajarin over a glass of something natural was an alumni who’d stuck around. “Book now for graduation,” they advised. I thought that was a bit alarmist for a restaurant that was neither in a hip, urban center nor had a Michelin star.

It was not.

Three years later, and reservations are still snapped up the second they’re released–back then, six months in advance, though Gemma has recently changed the system to only allow bookings four months out. When we arrive on a chilly December Monday, however, there are no signs of the throngs out front, just a stray tabby waltzing by. Mondays and Tuesdays are Gemma’s days off, and we’re not even sure she’s going to show. We made the appointment last Thursday, and all attempts to confirm have gone straight to voicemail. It’s not looking good.

But, we learn, people of a certain generation don’t require constant confirmation, and the commitment prevails. Practically on the church chime, a tuft of white hair pops out from a second-story window. “The door’s open!” she calls down, and we let ourselves in. (She would later tell us that she hates when people are late, and I thank my lucky stars we were on time; I’ve never been much praised for my punctuality.)

Among her adoring fans

Da Gemma has all the markings of a classic, provincial trattoria: simple wooden tables, entry rugs of questionable taste, a mishmash of dusty tchotchkes. But a photo album’s-worth of who’s who, from heads of state to actors, line the walls, belying any sort of humility the space, or Gemma, exudes.

A Roddino local, like her mother and grandmother, Gemma is ever the Piedmontese. Affable, but only after a few minutes of warming up, with opinions on her guests as firm and clear as those for her food. “I feel very sorry when people reach the top of this staircase wanting to eat, and I don’t have a table to give them. Then, maybe someone who booked doesn’t come and doesn’t warn us. You think, ‘What a miserable bastard.’ I sent away people who came all this way.”

She’s a bit self-deprecating–“I really like sitting at the table and eating, you can tell”–and doesn’t easily get carried away. “It’s a little too much, a little too much,” she responds when we ask how she feels about her fame. “When it becomes a lot, that too becomes a job.”

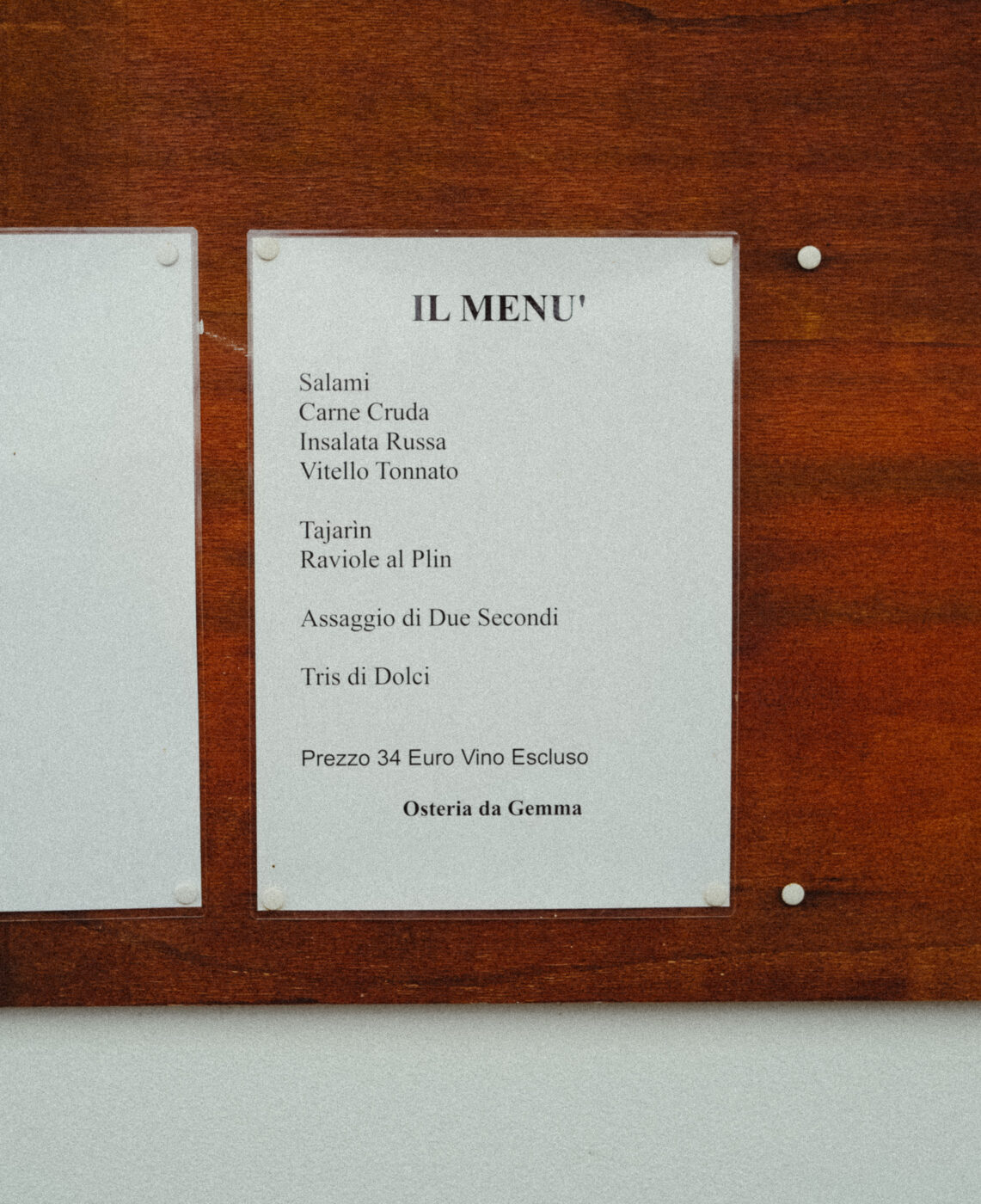

What she has become famous for, of course, is her food. At Gemma, you don’t order, you sit, you’re served, and you eat. Open for lunch and dinner five days a week–and feeding 70 to 90 people a service–Gemma offers large, family-style portions of Piedmontese classics, no embellishment, no variations on the theme. The antipasti are always the same–insalata russa, vitello tonnato, carne cruda, and salami, delivered with a knife to carve off as much as you want–as are the primi, tajarin and ravioli al plin. Secondi change daily, but you’ll get two of them–sometimes rabbit, sometimes wild boar–with vegetable sides. Dessert comes in three: bunet, meringue with hazelnuts, and panna cotta. The whole thing costs you €34, plus the price of wine, with bottles as low as €10 on offer.

What she has become especially famous for is her tajarin, the only overlap between Italy Segreta’s “The 25 Essential Pasta Dishes to Eat in Italy” and The New York Times’ listicle of the same name. Though the skinny noodles known elsewhere as tagliolini are typically topped with a sauce made of salsiccia di bra in these parts, Gemma makes hers with a beef ragù, explaining that she only sources meat that she knows has been raised in the proper, ethical way. “I get [the beef] from two butchers here in the area, one from Doliani and the other from Borsolasco. They source the animals here in the area,” she says. “I never cook pork or chicken, because they are intensively farmed meats. What I don’t eat, I don’t serve to others.”

And though the historic recipe of tajarin gilds the lily with 40 egg yolks per kilo of flour–a callback to Piedmont’s royal days–Gemma uses just 12 to 13 whole eggs. “I do normal things,” she clarifies. “My mother used to make them like this.” At home, she explains, it would be a waste to shell out for so many eggs. The pasta is “gently” rolled out by hand; Gemma claims it’s the only way to preserve the pasta’s vibrant yellow color and tender texture.

Tajarin

Rolling out what becomes a 10-meter-long sheet of dough is an effort she doesn’t take on alone. Thursday is pasta-making day, when the other women from town (and sometimes a few visitors) join Gemma in the auxiliary pasta room, with tables that unfold “like a book” to become work surfaces. In terms of how many hands she can count on, “It depends on the day. Sometimes 7 or 8, sometimes 10, sometimes we don’t even fit. If there are only a few of us, I get help from the young ones who I pay. The others aren’t paid: they do it for amicizia [friendship].” One such friend recently took it upon herself to count the number of ravioli they make per week: she came up with 11,000. Once they finish, they eat lunch all together. A few hang and then go home–extra tajarin, when there is some, in hand. We curse ourselves for not coming on a Thursday.

This–elder women of the village making pasta together–sounds like the type of scene we’ve encountered in homes across Italy, and, in fact, Gemma’s quite insistent that’s she’s a home cook, not a chef, reiterating several times throughout the morning that here is where you eat “like at home.” What she knows doesn’t come from culinary school or cooking programs–she learned to cook from her mother and grandmother, and 50+ years on the job.

Before Da Gemma, Gemma cooked at Roddino’s circolo, whose miniscule kitchen was 3 meters by 2 meters. “The entrance door to the kitchen was lower than normal. And I only had a small window up high that every now and then I could see the moon pass by at night. So I was basically in jail.” We gasp when she tells us she worked there for 19 years. “I’m resilient.” It’s no wonder the kitchen (and the dining room) of Da Gemma–previously a stable, which Gemma spent two years renovating–features expansive glass windows, with views on views of the hills beyond.

Views from the dining room

Gemma already had fans when she cooked at the circolo–she fires off names of notable patrons like Antonio Albanese, Gigi Garanzini, Carlo Petrini, Max Gazzè, Enza Sampò–but it all really took off when she opened Gemma on February 11th, 2005.

Depardieu was the first celebrity to come (“he loves to eat and knows how to appreciate good food”), then there was a feature in Vanity Fair (“I never knew who came and wrote the article”), and then there were television bites and newspaper articles and blog posts. Though Gemma claims all the attention can, at times, “bother” her, there’s an obvious undercurrent of gratification as she shows us photos of esteemed guests. Other accolades are also hung with pride: an honorary diploma from UNISG (“too bad it’s fading though”); a photo taken by famed photographer Guido Harari, who dressed her up in a nun’s garb made of pasta with a crucifix fashioned from a ladle and a slotted spoon.

Gemma beneath the Guido Harari photo

One would think that Gemma’s success would have had a ripple effect on her tiny town. But Roddino, just 440 strong, for the most part follows in the footsteps of much of rural Italy. “When I opened the circolo, 38 and a half years ago, there were many people who lived here. They were already old people, and now they are all dead. And the houses are empty,” Gemma reminisces, “but in the last two years someone has wanted to come back.” She’s seen five or six families of the younger generations fighting the tide of depopulation–people from Roddino who left to bigger cities like Rome and are now returning. There’s one family who’s already moved their residence here, renovating their father’s house in preparation for a move. Then there are the foreigners who’ve bought, “but they come for 15 days a year. Then the houses are closed.”

All of it begs the question: what will happen to Da Gemma when Gemma herself no longer captains the stove?

Gemma’s cousin mans the kitchen with her–but she’s one year older than Gemma. Following in the Piemontese tradition of women in the kitchen and men in the dining room, Gemma’s son runs front of house. Her daughter-in-law helps out every so often. But there isn’t really anyone she’s passing on her culinary secrets to.

I scan the room for signs of her son or daughter-in-law, for photos of the next generation. Instead, a large white and red blanket, stitched with “Da Gemma”, catches my attention. Gemma tells me it was hand-knit by her friends for one milestone or another. A photo of all of them together at the gift’s presentation hangs next to it, a dozen or so women with soft crinkled eyes smiling at the camera. “She’s gone, she’s gone, she’s gone,” Gemma points to various women in succession. Only two or three are spared.

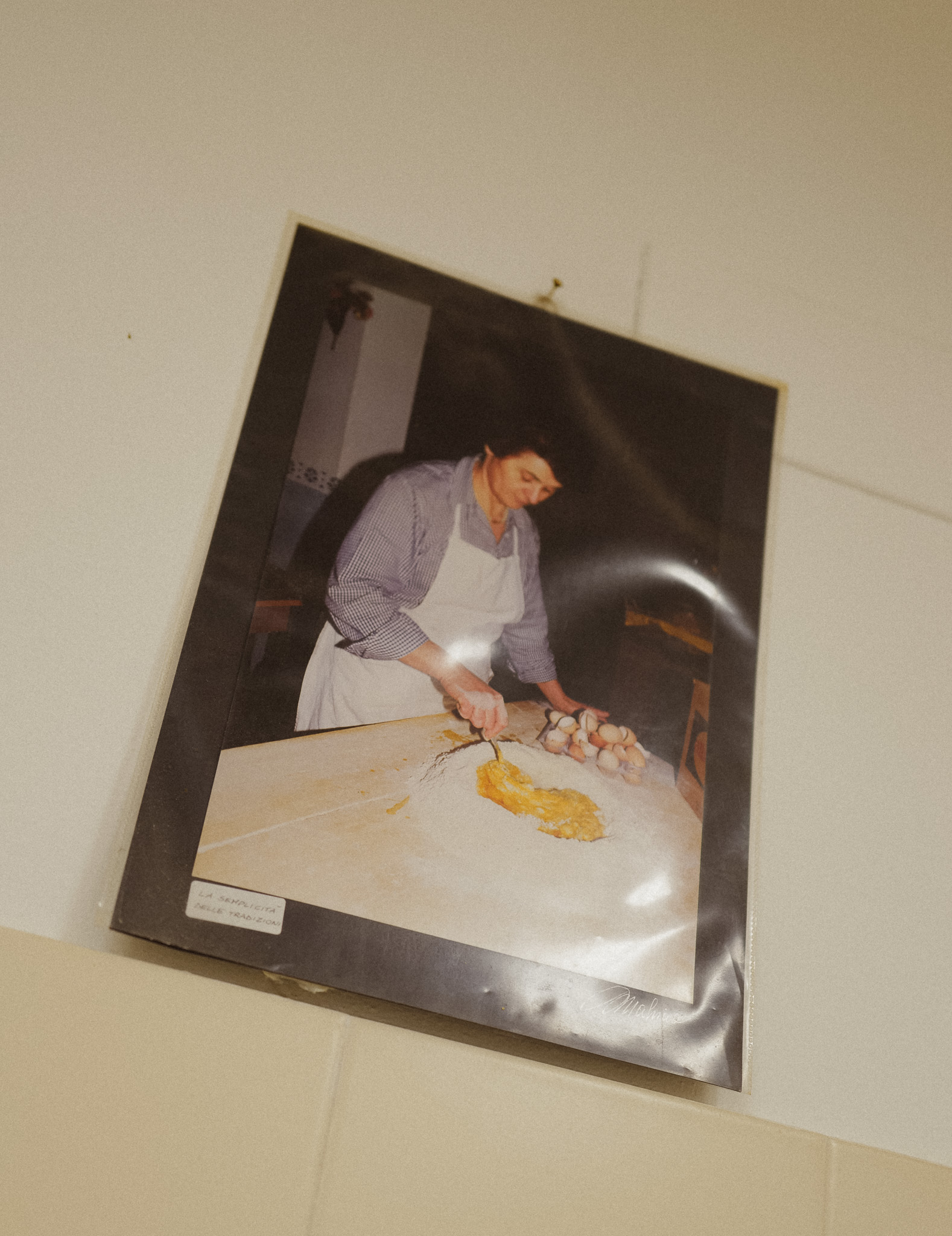

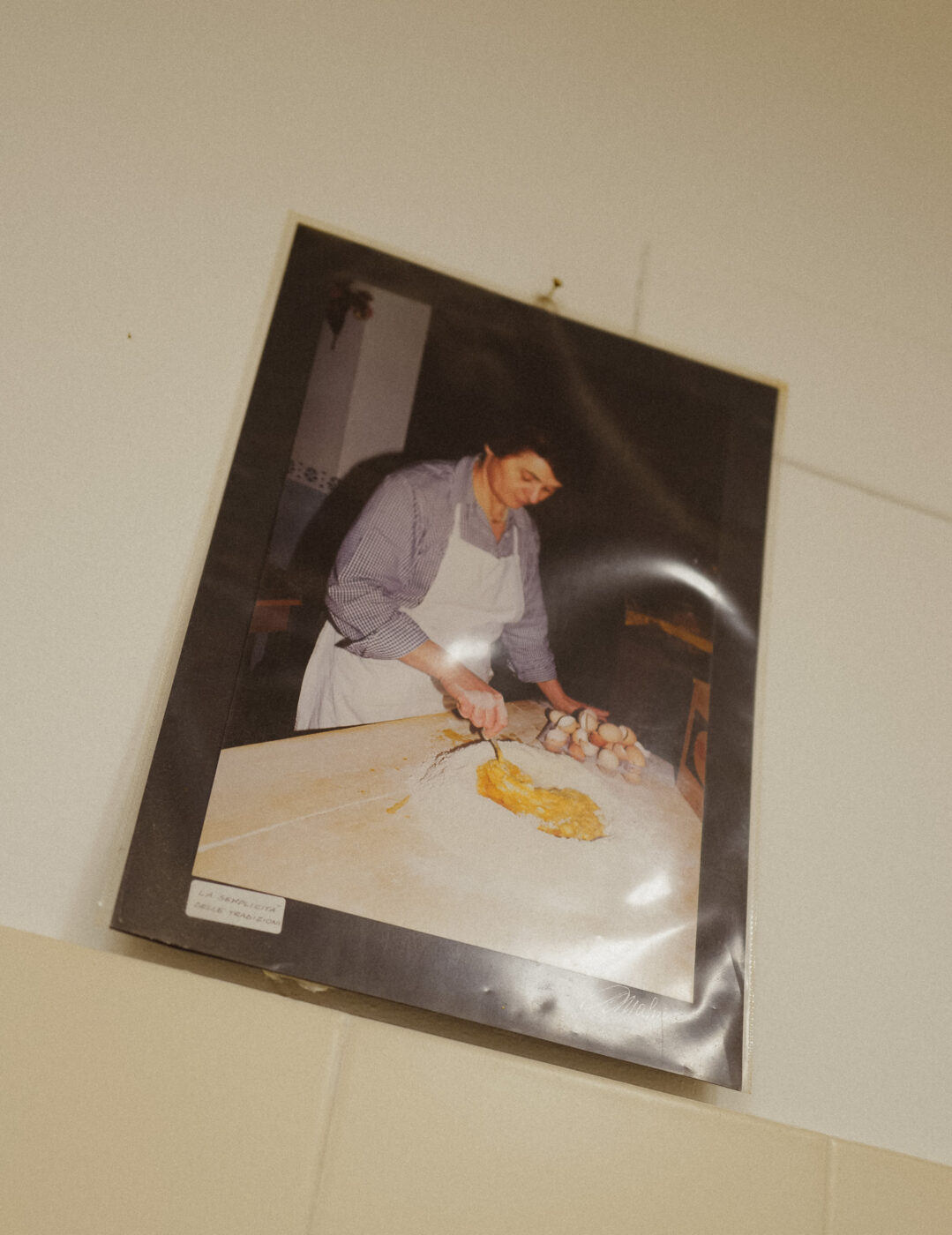

Next to it is a photo of Gemma–hair in the same short, blunt cut, but a youthful brown–making pasta side-by-side with her mother and grandmother, both gone now too. “Did you get a photo of that one?” she double checks, when we pass by it a little too quickly.

As we gather our things to go, she turns to us: “But everyone who wants to write about me… What is this story?” We tell her it’s a good one. “Yes, but then everyone else [in town] hates me because I’m always in the papers.” We assure her it’s just jealousy. But, honestly, it’s a good question. What is this story?

The truth is that hers is a story not so different from many across Italy–of provincial places where food is cooked from the soul and business is run on familial ties and amicizia. Of places that don’t look to the future, because it’s hard to say how much of one there is. I would argue that, beyond the simple fact that her food is darn good, Gemma unwittingly taps into the increasing desire for cooking that satisfies more than the stomach. People are tired of eating overly complicated things, craving the days before chefs were celebrities who rarely frequent their own kitchens. Gemma, on the other hand, sure as hell isn’t leaving her kitchen for the limelight; if Gemma isn’t there, nobody eats.

TV personality Antonella Clerici has invited Gemma to be on her show La Prova del Cuoco four times. “They came looking for me and brought me the CD to watch it, to make me go on,” Gemma says. “I’ve never seen it, and I don’t care. I don’t want to.” She scoffs at those who ask her to come to Milan or Rome for their programs. “I’m here working.” If you want Gemma, you’ll find her in Roddino.

The same glasses used for the last 38 years

Gemma doesn’t trend-chase. She doesn’t experiment with new recipes. She doesn’t even try to make that much money. She is perfectly content right where she is, thank you. And there are some, she notes, who are disappointed by this. “Since they always advertise me, they have expectations. But this is home cooking,” she continues. “Then there are those who are disappointed because I always use the same glasses. I’ve used the same model for 38 years. I change them because they break. Now I can’t find them any more and I’m very sorry. I have the same plates and the same cutlery. I’ve never changed any model of anything.”

Fame is a snowball, its descent down the hill spurred on by parrot-like algorithms. It’s blissfully refreshing to find someone who hasn’t rolled down with it… Though it probably helps that insalata russa is not particularly Instagrammable.

At Da Gemma, you can taste not where Piedmontese cuisine is going, but where it’s been. Book now for graduation.