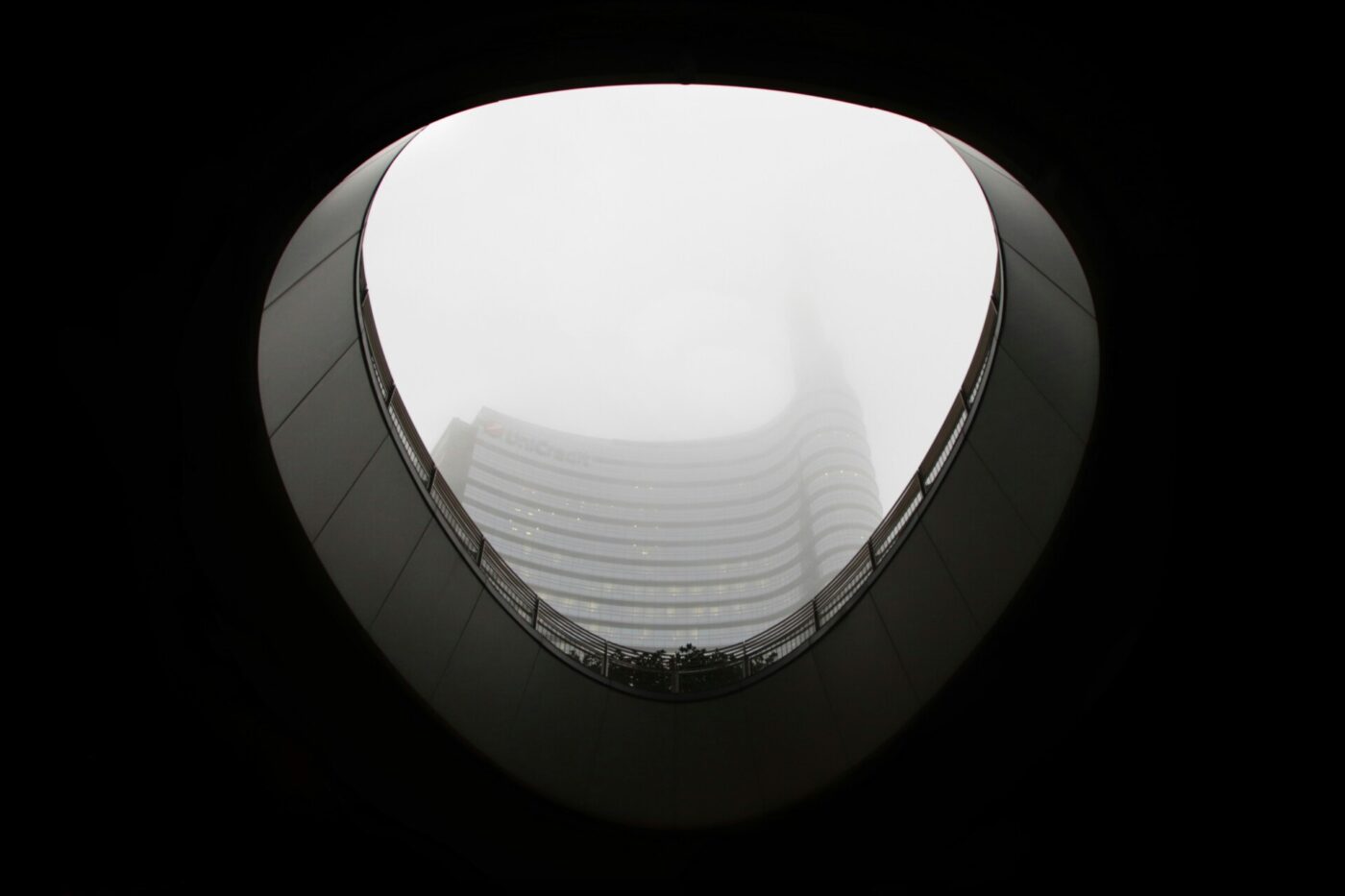

When people ask me for the most typical restaurant in Milan, I always answer Ceresio7–rooftop above the Brian&Berry Building with a pool, cocktail bar, populated by girls in miniskirts and men with sports cars. I do this somewhat provocatively, and not because Ceresio7 is not great, but because those who ask me would like, as an answer, an old-fashioned trattoria where they can eat “like in the old days.” The problem is that no one in Milan has ever wanted to go eat “like it used to be.” The past has just never been loved as a concept; “once upon a time,” Milanese looked to the future. Their black-and-white postcards depicted futuristic electric streetcars, the Fiera pavilions, the Pirellone skyscraper, and the twinkling lights of La Rinascente, not the Navigli and the railing houses. (Milan is full of palazzine of popular architecture composed of small apartments accessed by a long common balcony with a bathroom at the end. Today, renovated, they have become real bijoux.) And yet today there is a pervasive nostalgia for “Vecchia Milano”, the “old Milan” that has never historically been appreciated.

Courtesy of Ceresio 7

I am Milanese, daughter of two Milanese, but with a surname that betrays other origins–which is the most Milanese thing there is, as people have moved to the city from all over Italy (and beyond) since the postwar period. The most common surname among newborn children is Hu, because Milan is home to the most populous and oldest Chinese community in Italy. Many claim that Milanese people do not exist, but that is not true: people turn Milanese, and for a century they have done so unwillingly.

Gray, cold, choked with fog and smog, Milan has always been described as a modern but ugly, alienating place devoted to the secular religion of work. Writer and journalist Guido Piovene in 1954 described it as “a utilitarian city, demolished and remade according to the needs of the moment, therefore never managing to become ancient.” Milan is a cannibalistic city, devouring itself, and it has done so by burying rivers and demolishing entire neighborhoods and a good part of the restaurants and trattorias where today we would love to go instead.

The Rediscovery of Milanesità

The emergence of Milanese nostalgia all happened with the run-up to the World Expo of 2015, an event that managed to reawaken a Milanese pride not seen since the 1990s. Pavilions and fairgrounds aside, it was an obvious turning point, not only in urban planning but especially in the narrative of Milan, internationally and among the Milanese themselves. Locals fished out Milanese dialect for their signs, costolettas returned to menus, contemporary trattorias revived historic ones, and hipsters helped make the aesthetics of nostalgia cool. Milan reaffirmed its identity by digging into its avant-garde past, and while, on the one hand, it built new skyscrapers, on the other, it infused the old walls with new values.

Expo 2015; Photo courtesy of Fred Romero

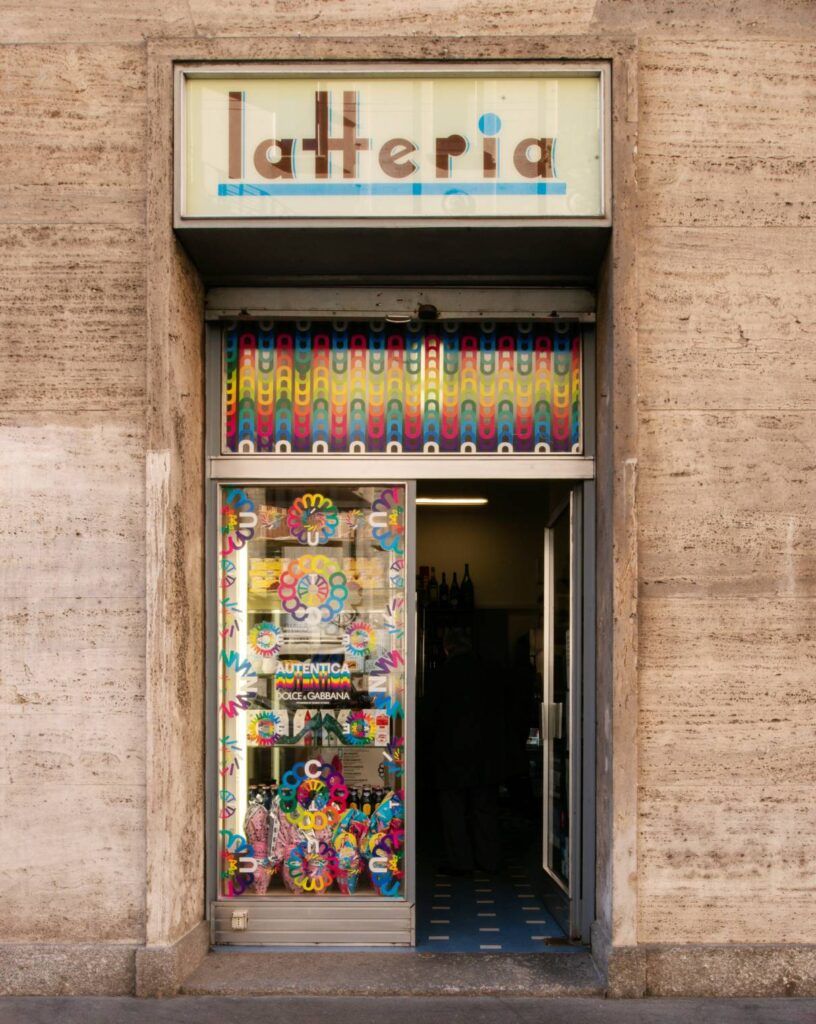

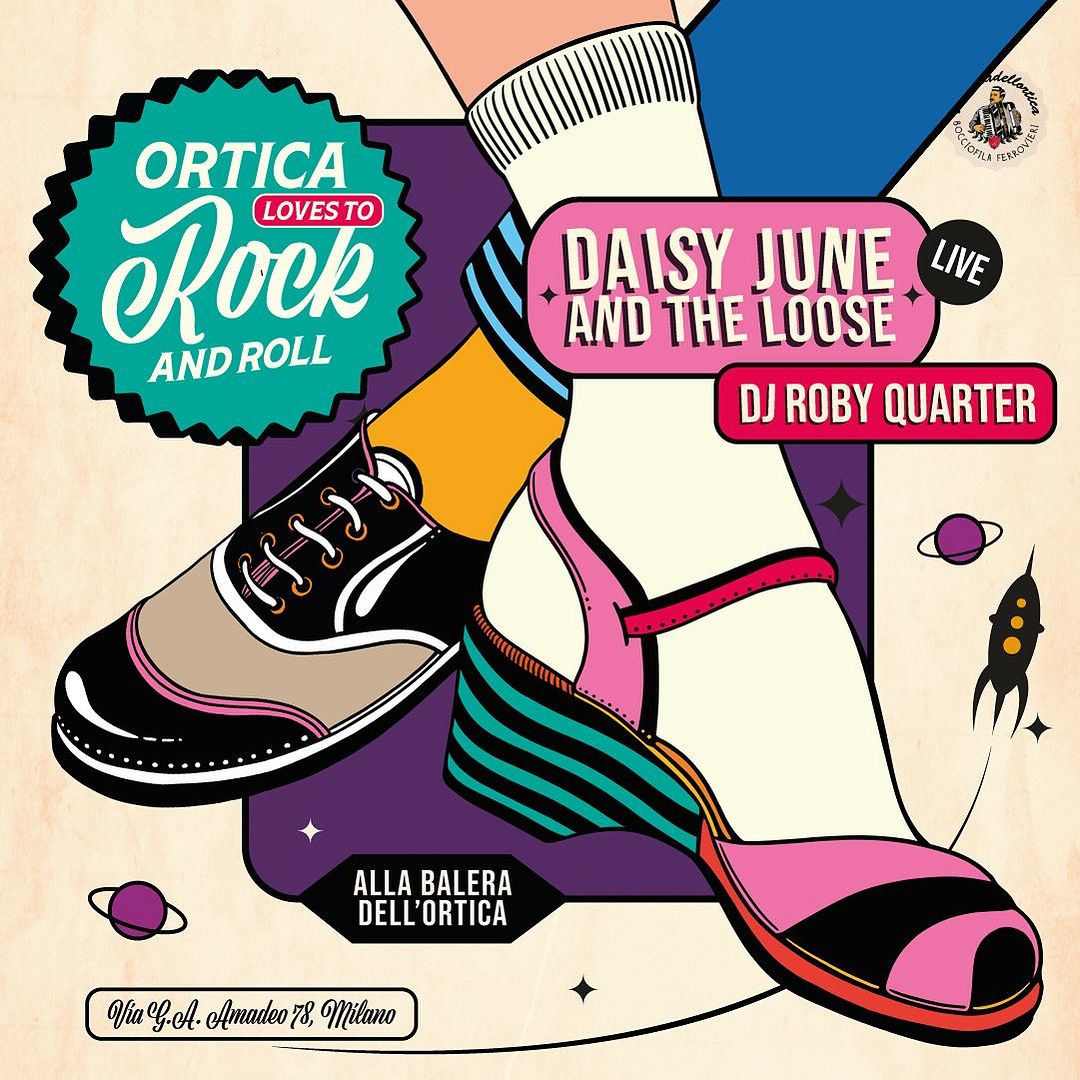

The city has kept the frame but changed the content, and so creatives and Bocconi students hang out in neighborhood bars like Bar Picchio, models and the fashion world go to Latteria Carlon (after the Dolce&Gabbana takeover a few years ago), one sits on recycled fruit crates on the street drinking champagne at Cantine Isola, Bar Basso gets crowded at every Milano Design Week, and even Giannasi 1967, the city’s most famous roast chicken stand, has done merchandising and collaborations with underground designers. Provincial bowling alleys have morphed into trattorias, like the Trattoria San Filippo Neri, and at La Balera dell’Ortica they no longer dance ballroom but rock’n’roll. Those who have not evolved have not survived, as is tradition in Milan.

Caffè Picchio

How to Live the “Old Milan”: Between Brioche and Bitters

Milan is not beautiful. It does not hit you at first glance. It is not Rome, it is not Venice, and to understand it you have to live it with its rituals. Partaking in aperitivo and, lately, lining up for breakfast are two of the most transversal and foundational moments of sociability in the routine of the Milanese.

City of Campari

Before the Spritz with Aperol invaded Italy (a decade ago) and the rest of the world, people in Milan drank Campari, a Milanese bitter with an outpost in Galleria Vittorio Emanuele. At Camparino in the Galleria, locals would gather for a Campari Seltz at the bar (and can still be seen doing so); at Bar Basso, for a Negroni Sbagliato in the giant “big glass”; or to drink one for the price of two in a very normal neighborhood bar. A small bottle of Campari Soda, white wine, and ice, aperitivo at the bar–before the era of happy hour and the all-you-can-eat buffet–was boiled down to a few chips, two peanuts, and then it was off to dinner or home. The “one for two” is no longer drunk by anyone, but the ritual has remained that of “Campari Hour”, to quote the song from an old commercial, at 7 PM. Sitting at a plastic table at Caffè degli Artisti or served and revered at Pasticceria Cucchi, to feel like a true Milanese sciùra, it matters little, you relax after work. You go out, meet, eat, drink and go home. More than lunch, more than dinner, you meet for aperitivo.

Weekend Brioche

Brioche with cream (in Milan, we use “brioche” instead of “cornetti”) and cappuccino (strictly before 11 AM). Breakfast at the bar is an urban ritual. You make it on the run during the week, under your house, leisurely on the weekend with the newspaper under your arm, today even by standing in line–standing in line for something being a relatively new concept in Italy. (In Milan, a post-covid phenomenon.)

If you ask me the truly Milanese place to have breakfast, I’ll tell you Loste Café, a Danish-style bakery famous for its cinnamon rolls. People cross town to go there and stand in line for more than an hour. It sounds as provocative as answering Ceresio7 but the truth is this. At Gelsomina, you queue up to photograph the maritozzo that has gone viral; at Pavé, the brioche “Centossessessanta” with apricot jam or “La Rossa” with raspberry remain objects of desire years after their creation, and if you ask me where to go for breakfast, I recommend these places. The quality of Loste, of Pavè, of Marlà is very high; they are the new tradition in Milan, but they don’t have anything made “the way they used to be.”

Pasticceria Sissi

The historic pastry shops, rather, have pink tablecloths, paper doilies, boxes of chocolates in plain sight, display cases with pastries and that scent of vanillin in the air. Places where they don’t know what cold brew is and where they avoid any kind of innovation, even if, with new cooking techniques and fancier ingredients, they could better the classic recipes or add something contemporary: they won’t, that’s the point, and that’s the true secret to the “good old days” flavor and the romantic vibe. At Pasticceria Sissi, the brioche cut in half and filled with custard arrives with a vintage napkin; at Pasticceria Cucchi, they still make traditional rice pudding; at Pasticceria Gattullo, you choose a few pastries sprinkled with powdered sugar and wait for your cappuccino with a heart of foam drawn on it. Time there seems to have stood still, but it is only a stage set in which the actors are the last elderly “from Milano-Milano” and those who have arrived here more or less recently and do not yet know how long they will stay. But while they are there, between breakfast and aperitivo, they both feel like Milanese in Milan.

Pasticceria Cucchi

Where To Find Traces of the “Old Milan”

Caffè degli Artisti – The alter-ego of Bar Basso, across the square. An anonymous old neighborhood bar that has changed management but nothing of the decor and is the low-cost hangout for young kids and people from the neighborhood.

Bar Basso – Iconic bar of the Milan scene that brought mixology to the city. This was the birthplace of the Negroni Sbagliato, which, thanks to its proximity to the university’s Faculty of Architecture, is drunk in a large designer glass wanted by the historic patrons themselves. A place beloved for generations.

Bar Picchio – A bar, a very normal bar, that has been taken by storm for a few years now, from aperitivo time until midnight, by people drinking small beers and spritzes in plastic cups, standing or sitting on the sidewalk in the street.

Giannasi 1967 – This spit-roasted chicken and takeout stand has been a Milanese icon since 1967. At night, there is a line for takeout, but by now it has also become a destination for having an aperitivo with a beer or eating in the patch of grass that surrounds the kiosk. Their merchandising makes great souvenirs.

La Balera dell’Ortica – This huge, historic dance hall features an outdoor dance floor and large table rooms with evening entertainment: swing, rock’n’roll, vintage markets, dance classes, but also bocce courts. There’s also a trattoria serving arrostini and a weekly changing menu of Italian cuisine.

Trattoria San Filippo Neri – It only opens a few evenings a week and closes early (they raise the shutters at dawn), so you always need to book in advance. The menu is extensive and affordably priced. In the summer, it’s lovely to sit outside under the wisteria–the perfect spot to enjoy a plate of lasagna and soak in the atmosphere.

Pasticceria Cucchi – This historic pastry shop, open since 1936, is where you can cross paths with the gentlemen of the neighborhood. Order breakfast with rice pudding and cappuccino, toast, or aperitivo served on the riser like a five o’clock tea.

Pasticceria Sissi – There is always a queue, people crowd in, but there’s no need to be afraid, it flows smoothly. Here you eat brioche cut in half and filled with custard, chocolate cream, or both.

Pasticceria Gattullo – Open since 1961, Gattullo is a great classic. The opulent counter is overflowing with mignon, but a sandwich for lunch will surprise you.