Waking up in Italy for the first time in two years felt surreal. It was my first time being back since my break-up, my first time being back alone without family, and my first time without my nonna. A week before I left Australia, she passed away. We celebrated her life just days before I boarded the plane for Europe and, on that first night in Italy, she came to me in my sleep. I dreamt about her so vividly, it was as though she was sitting right beside me, wine in hand.

“Ciao, Laura!” she said, her arms waving around passionately.

“Say hello to Donato for me!”

“Did you find a boyfriend there? A nice Italian boy?”

“I think it’s time for a Campari spritz.”

Her warm, husky voice faded with each familiar phrase, further and further away from me, slipping through the cracks of the sandstone buildings that surrounded me as I snoozed in the sleepy streets of Savona. I didn’t want her to go, but I felt sure that she would still be with me when I woke up. Because I was in Italy.

Donato had come to pick me up from the nearest train station in Genova. “I’m hereeeeee!” he’d sang into the phone in a familiar voice that radiated pure happiness. As we’d whizzed through the windy streets back to his house, there wasn’t a moment of silence.

He cooked dinner for Luca, another friend visiting, and me–a traditional Abbruzzese classic of sagne e ceci (pasta with chickpeas), complete with a few bottles of Montepulciano–and I couldn’t help but feel nostalgic. It was all so familiar to me. The muted green kitchen tiles with embossed flowers and the occasional hand-painted scene of a jug to remind you that you’re in the kitchen. The white light bulbs lit up in oversized fixtures so that they’re actually kind of dim. The concrete tiled floor that is somehow warm underneath your feet. The smell of salami and cheese and freshly cooked pasta. The doors that never quite close properly. The clothesline hanging between your kitchen window and someone else’s balcony. The window ajar casting more light and life into the room than you thought possible.

I didn’t grow up in Italy, but the scene and the sounds and the smells feel like they’re a part of me. My nonna and nonno’s house didn’t have a clothesline hanging from the window, but it did have a garden full of chillies and chickens. So much of what they built in Australia was similar to Italy–the kitchen tiles, the checked tablecloths in every color, the sound of overlapping enthusiastic voices, the pasta, the singing, the love.

I was starving from an evening of travel, so, as the food cooked, Donato threw a fresh salami and a block of pecorino cheese on the table, and I started to chop. “Like a true Abbruzzese girl!” he said. This felt familiar too; me chopping up wedges of things to eat and feed to others. We cheersed our Campari spritzes, complete with a labeless prosecco “made by a friend”.

Sitting there, in that kitchen, I felt truly at peace for the first time in a long time. It was a different kind of peace than the one you feel when you do something great at work, or you clean the house, or cook a nice meal for your friends. It was the feeling of being in a place you belong.

I used to feel like this at my nonna’s house back in Australia, on Friday nights when we’d go for family dinner. It happened–without fail–every week for my entire life. Until I moved away and she got sick. It was such a consistent ritual that I barely noticed it. The antipasto, followed by pasta, followed by meat of some kind (roast chicken, polpetone, sausages), vegetables, and salad, followed by ice cream with coffee for dessert. God forbid you’d fill up on the antipasto’s meats and cheeses; you couldn’t miss a single course or you’d literally ruin her day. She dedicated her entire life to cooking and caring for people. Nothing made her happier.

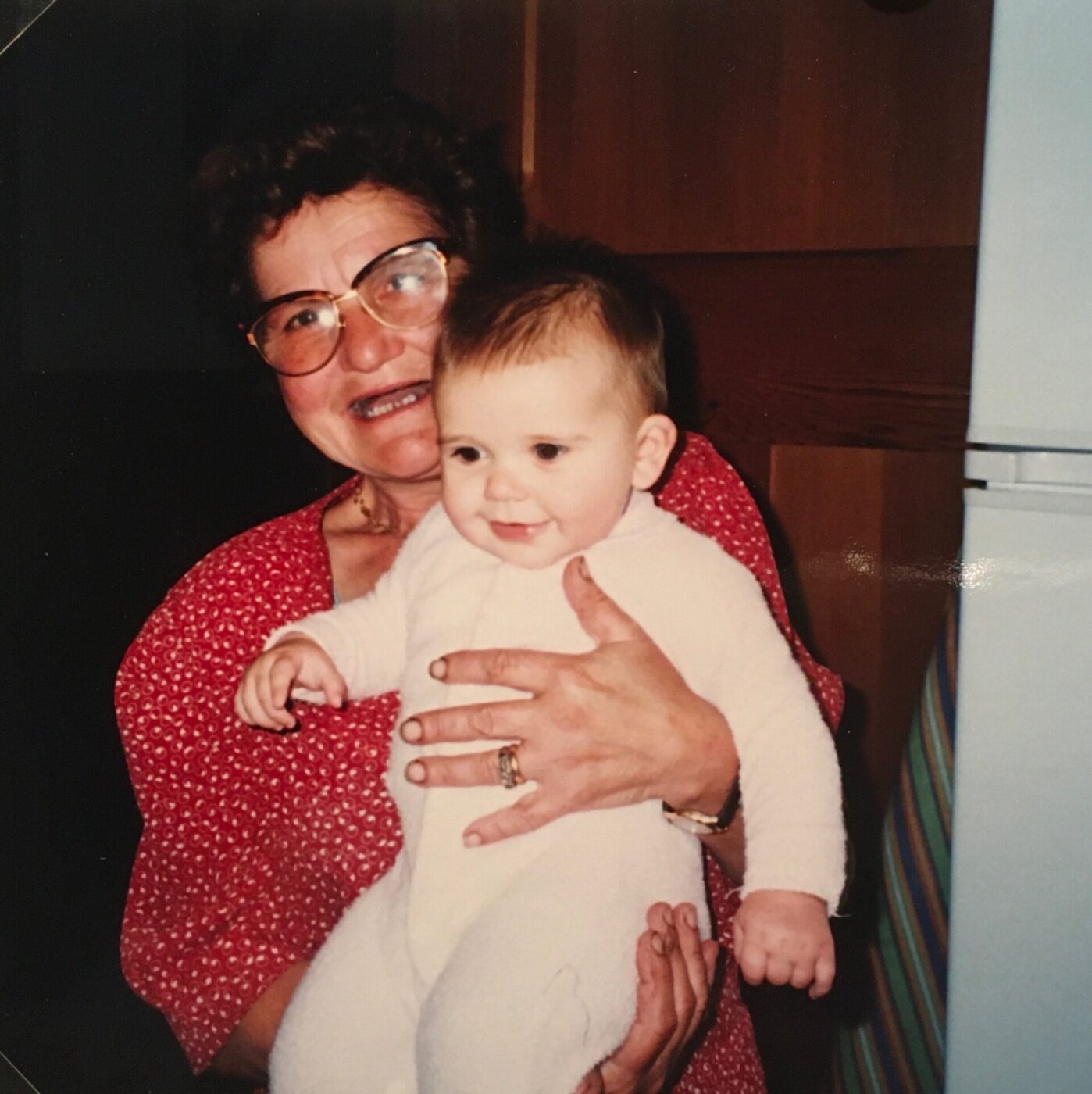

Laura and her nonna

The first time I went to Italy, I went with her. All of my Australian family hopped on a plane to celebrate biz-nonna’s (my nonna’s mother’s) 100th birthday in 2014. A week-long party, fireworks that lit up a neon red “100” in the sky, formal lunches and dinners, and family and friends from all over Italy arriving to celebrate ensued. I remember seeing my nonna in that environment, surrounded by her seven brothers and sisters, her 100-year-old mum, and us–her younger family–and just watching her glow with pride and purpose. It was like I was seeing her for the first time. I understood her and my dad and myself so much better. The way everyone fussed over each other; how they gossiped, but not in a caddy way. That people I didn’t know kissed me on the face within seconds of meeting me and any trace of social anxiety washed away. The chaotic organizing of plans that eventuated hours after they were supposed to but no one really cared because where else would you rather be?

Back then, I felt the same as I do now–overwhelmingly grateful. My nonna brought this culture to Australia and she created a little Italian heaven for us all to exist within. I didn’t realize how big this bubble was in my life, until recently. When they told me I couldn’t go to her house for pasta al forno anymore. When I went there for the last time, now empty, and realized how much sitting at that table every week meant to me. It was more than just a meal. The loving out loud, the overfeeding, the constant celebration, and the bold and shameless feeling of it all. This way of life feels intrinsic to me because it has always been my reality. That table was the place throughout childhood and beyond that felt the safest. I remember being in Italy ten years ago and thinking that everything finally made sense and I never wanted to leave. I felt like that this time around, too.

Since childhood, I’ve always felt confused by the way people communicate. I’ve never understood the urge to hide strong feelings, to push through uncomfortable moments of tension-laced silence in order to remain in control. I’ve always felt suffocated by the gray areas, the passive aggressiveness, the tit for tat, the score-keeping, the clicky, judgemental, too-cool-for-school exclusivity that oozes out of most social and professional environments I’ve been in in Australia. It exhausts me. And for so long, I didn’t understand why. I assumed that being a bookworm who was into competitive ballroom dancing naturally excluded me from other kids my age–and so I learnt to get comfy with being an “outsider”. It hadn’t occurred to me that the difference was cultural, until I went to Italy for the first time.

“I’ve really enjoyed spending time with you and getting to know you,” Luca said to me, on our last day together in Savona. Gabriel, another friend of Donato’s, said so too. “It’s been a pleasure. You are beautiful!” Other friends, Mery and Alessia, messaged me to say they loved meeting me and were so happy we got to spend time together. “Don’t go Laura, stay here with me!” Donato urged, in a voice that rarely anyone ever says no to (for good reason), and I didn’t want to be the first.

“Is this normal?” I asked him. “You’re always hanging out and going on adventures together and singing songs and drinking wine?!”

We spent every single night the same way. Donato would pick up his guitar and start to play. The girls would start to sing and dance. There’s no need to “dance like nobody’s watching” in Italy because everyone is watching with glee and will probably join in. At one point, someone brought out a keyboard. Another one played on bongo drums they had on hand. Each night was a different setting; at a friends’ villa on the mountain overlooking the Camogli coastline, at a playground in the Savona city center, along the port where all the boats are docked and the bars are overflowing, inside a little cave that we hiked to just outside of a town called Noli.

“Yes it’s normal, cugina!” He laughed. “This is Italy. This is life!”

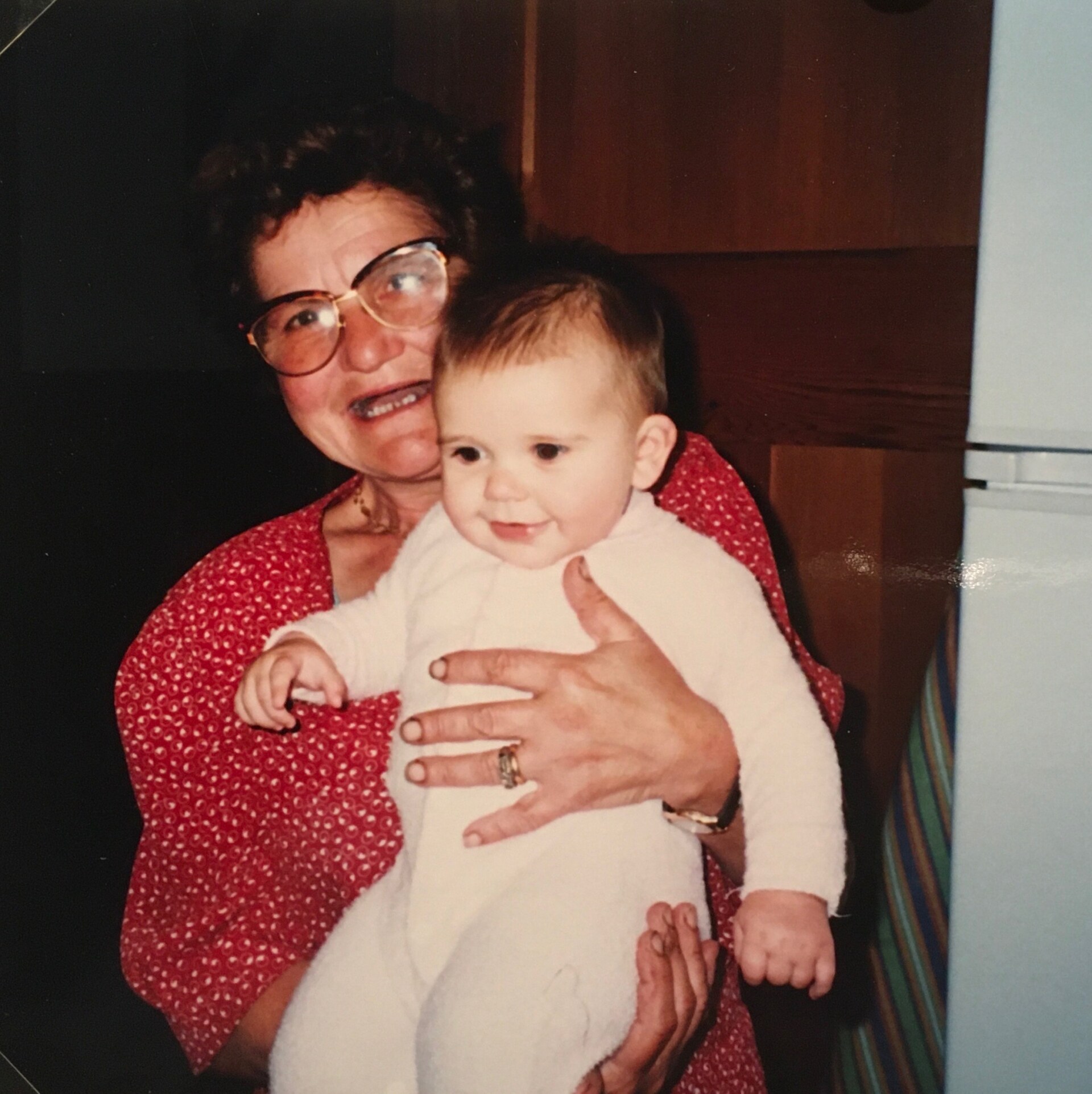

Laura's Nonna

It reminded me of my nonno singing opera at the dinner table every time we’d finished the main course. He’d sing at least two–maybe three–songs and my nonna could never hide her joy at hearing him sing and us clap. My older cousins and I would cringe with embarrassment if he’d do it in public, but he’d carry on without shame and she would encourage him. They both oozed pure gratitude for the simple and enjoyable things in life and, without enforcing anything, they initiated me into this world of thunderous joy. If we didn’t clap for nonno, she’d tell us off. “It was beautiful, eh?” she’d insist. And she was right. She was the playmaker, the one in charge of making sure that everyone was having a good time. Her love for the country she grew up in shaped my life. Her love for fostering full tummies and passionate words has permeated through me so fully that being anywhere but Italy doesn’t feel right. I see that now.

Some might say that her role of cook, cleaner, and housekeeper was oppressive, but, in her case, I think that’s bullshit. She took pride in it and was celebrated for it. Being in Italy has made me realize that I love to do those things too. I love to be appreciated for making a good moka, for chopping up cheese and salami, for putting on a nice dress, for singing loudly for everyone to hear, for dancing like crazy.

After a few days into my trip, I realized that I hadn’t felt stressed, tired, hungry, or alone the whole time I’d been there. Usually, I feel at least one of those things every day. My throat was a bit sore from singing so loudly, but it was mere evidence of all the fun. I also realized that the reason I don’t feel at home in Australia is because the home that was created around me felt a lot more like Italy. At my nonna’s house, I felt at home. Here in Italy, I felt at home. I felt open and affectionate and ready to love in a way that was instilled in me by my nonna because of her love for family and for her culture. I struggle to love that big sometimes; I struggle not to live in fear of being hurt or taken for granted. But that struggle didn’t exist in Italy. I think I am more like her than I ever thought.

“You belong to Italy,” the boys echoed during dinner on my last night. The words rang so true to me that I almost wept right there into my cheese-filled focaccia because what was I going to do? I felt compelled to find a way to stay.

And so, as I sit here, now on the train back to London–actually sobbing because my heart is aching–I also feel relieved to have found my place in the world. Some people search their whole lives to find places and people that feel like home, and a big part of me had still been searching. But now, it hit me harder and faster than the train I was whooshing away in. I’d lost my nonna and found myself in her birth land. The space she left behind made it clear to me; I already have my home in Italy.