A missed bus to Florence, torrential downpour, no umbrella, and a suitcase on the verge of breaking was as bleak as my day could get at 9 PM. As I waited for someone to let me in the hostel that once used to be a convent, I mulled over my options for dinner. At this point, I lacked the patience and spontaneity to search for something online and try a new restaurant. The only correct answer to my dinner problem was, of course, the supermarket.

I have always loved supermarkets. Maybe it’s the domesticity of it, or perhaps I am just a romantic. There are so few things in life you can count on: an Italian supermarket is one of them. It does not matter whether it is a Conad, Esselunga, Coop, or any other–it’ll always deliver.

I love the variety of each aisle and each section. There’s the produce section with its mauve radicchio, blood red pomodori, the budget pack of assorted salad leaves, lush fagiolini, “extra premium” ananas, malachite-shaded cipollotti. The deli counter with meat cuts and a PDO-certified selection of cheese. The wine section with illustrated landscapes and poetic descriptions on its labels. The compartments with vegetables, soups, and meals that are frozen for convenience. The familiar, square corners of boxes of spaghetti, the chocolate eggs during Easter, the pastel packaging of panettone at Christmas–all comforting sights, all available in an Italian supermarket, no matter how big, no matter where in the country.

Love…

After several failed dates, I joked to my friends, “Maybe we are supposed to meet the love of our lives in a supermarket.” The following week, I came across an article recommending supermarkets in S. Agostino in Milan as a place to find love. When I shared this, my classmate Andreas nodded and told me about how a few years ago two flatmates took it upon themselves to host a speed dating event at Esselunga. They posted an ad on Facebook, promising singles an opportunity to meet their potential soul mates. Because nothing elicits romance like the promise of shared domesticity and fresh produce like a supermarket. If nothing else, you could always go home with a good bottle of wine. The format started in Milan, and its success prompted it to further repeat in Bergamo and Turin. A supermarket playing the role of a matchmaker is stuff out of a Modern Love episode.

… And War

But it’s not all mozzarella and love stories. Supermarkets in Italy have politics of their own. Or rather, their allegiances to political parties. It’s not a secret that Esselunga’s owner, Bernardo Caprotti, is a strong supporter of the PdL–Italy’s right-leaning party,–and its former leader Silvio Berlusconi. His sentiments towards another supermarket giant, the left-leaning Coop (Ipercoop), have been made clear time and time again, and have been well-documented in the media. The most memorable instance being an ad in the newspaper wherein Caprotti protested against Coop’s monopoly over a piece of land in Livorno. But the feud reached its climax with the publication of Caprotti’s book, Falce e Corello (Sickle and Cart in English). In the book, which more or less reads as a series of grievances against Coop, points fingers, names names, and tries to scapegoat the rival grocery store for building over Etruscan ruins, amongst other gripes. While the feud between these two giants seemed to be at an all-time high in the 2010s, the relaunch of the book in 2021–with further statements from Caprotti’s daughter Marina, the current president of Esselunga–has reignited it again. In this instance, the pen seems to certainly have been mightier than the sword because the publication of the book led Coop to take Caprotti to court for a series of defamation claims, and some supporters even rallied to try to have the book banned.

Italians take their supermarket allegiances as seriously, if not more so, than their football teams. After Esselunga began to offer home deliveries of groceries in Turin in 2010, La Stampa published an article all but warning its readers to stay strong against falling for this convenience, so as not to let the city, the only left-leaning stronghold in Piedmont, fall to the fascists. To this day, there are signs and graffiti plastered around Turin’s main bus depot on via Vittorio Emanuele II, decrying Esselunga’s presence in the city.

Rather than identifying our political leanings on Bumble or Tinder, maybe we should instead be evaluating our potential matches on which supermarket they shop at. Evidently, one’s supermarket of choice can tell you a lot about a person. But of course, not everybody can afford to shop solely based on their morals. In 2007, a report produced by Altroconsumo noted that prices were lower in cities where Coop and Esselunga were present. Another report also noted how Milanese preferred Esselunga as it was more cost-effective. Food is political–there is no doubt about that–however, considering socioeconomic barriers while purchasing sustenance is also essential. It’s a privilege to be able to choose where you buy from.

Esselunga's Controversial 2023 Advertisement

Coop's Controversial 2023 Advertisement

To The Source

But when we get down to the baseline of ethical food purchasing, it’s really not about supermarkets at all. The only Italian I know who buys vegetables from a farmer is my friend Francesco. “They are quite expensive, but it’s worth it,” he told me sheepishly. This was the beginning of a long series of what I would later call “Revelations About Italy” on my iPhone notes. Like so many foreigners, my Instagram was flooded with images of mercati lining the streets and piazzas, the piles of produce abundant, the prices handwritten on a chalkboard, the proprietor of the stall sweet and old and devoted to their produce and its quality. But the reality remains that most people buy their products from supermarkets because it’s feasible. Sure, there are certain farmer’s markets where you can shop direct from the producer for the same price, or often less, than a supermarket, and, if you know where to look, you can find bakeries and butchers that are both sustainable and cost-effective. Especially in city centres, supermarket prices are inflated and it makes sense to shop at local alimentari. But the reality is that most working Italians can’t coordinate with the opening times of these markets and various small businesses–most of which keep the same hours as offices and close from 12-3 PM daily, as well as on Sundays–with their busy schedules. Supermarkets are open (almost) every day, from morning through night.

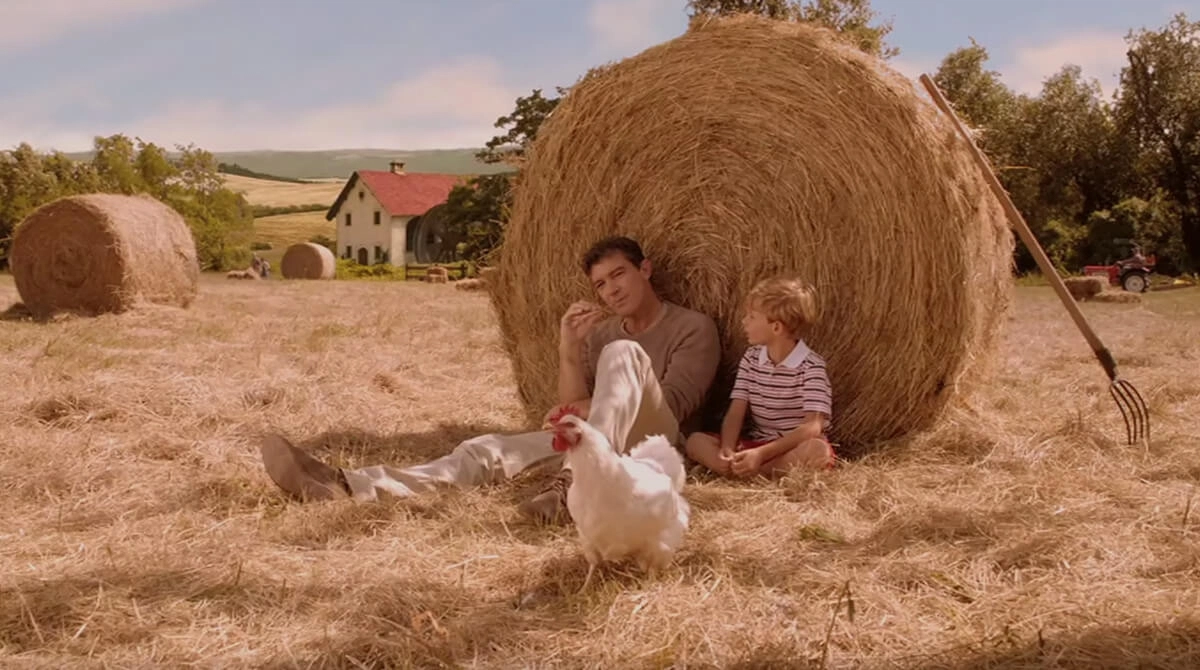

Mulino Bianco's 2012 Advertisement

So many of us harbour the Italian dream of always eating fresh, but Italians too indulge in processed food. As in America, the post-war period in Italy was marked by capitalism swooping in, and with it, a redefinition of the country’s dietary codes. The Mediterranean diet–made of lean proteins (usually fish), lots of fresh fruit and veg, olive oil, and an emphasis on eating fresh and seasonally– which used to be the default way to eat in Southern Italy, especially, has long been considered as the healthiest in the world. But, thanks to recessions and mid century capitalism, between the 1960s and 2000s, the Italian diet shifted away from this fresh, seasonal model and towards more complex carbs like pasta, refined sugars, and pre-packaged foods. There were campaigns–sponsored by giants like Mulino Bianco and even the government–that cited meat and eggs as unhealthy, and sugar as a necessary source of energy for kids. A now-infamous TV ad from the 1980s goes so far as to recommend children eat a spoonful of sugar to help brain development. Jeannie Marshall, author of The Lost Art of Feeding Kids, has noted that “industrial food is often marketed in Italy as traditional, local and part of the culture. Mulino Bianco uses bucolic imagery of perfect rolling hills and farmland to sell processed foods and snack cakes.” As a result, Italy’s childhood obesity rate is amongst the highest in the world. Still, in Italy, thanks to such a strong emphasis on tradition and the sheer geography of the country, which boasts the capacity to yield some of the best produce in the world, there is an underlying awareness and familiarity with fresh, seasonal eating. And, unlike the food desert-plagued US, these types of food are much more accessible. These days, many young Italians are also picking up their grandparents’ farming practices and regenerating local foodsystems.

In reality, Italy’s streets put pasticcerie, delicatessens, pescivendoli, enoteche, and forni shoulder to shoulder with Conads, Esselungas, and informal minimarkets, often run by Desi people. From convenience to economy to politics, the consumer reasons behind which to shop at are as layered as lasagna (excuse the pun). Maybe one day, I will go to local markets instead of these supermarkets, relishing whole days spent hopping from one shop to another, with nothing but quality as my concern. Till then, I will relish the joy of the ready-to-eat section of Italian supermarkets and their familiar discount announcements; and maybe, just maybe, there’s a meet-cute in my future with somebody who feels the same.