The story of Mina is almost mythical: she seemingly stumbled into the spotlight at 18 on La Bussola’s stage only to become one of Italy’s most famous singers, kicked off of RAI in 1963 for her “affair” with a separated man only to be brought back through the sheer fervor of her fans, reaching the pinnacle of what fame can be–only to retire completely from the limelight at the ripe age of 38 in 1978 and never come back… Exactly.

And it is Mina’s songs themselves that tell a story of a woman sometimes in love, sometimes in lust but almost always self-possessed, sure of something. As an American, my first experience with Mina—I’m ashamed to say—was at Rome’s “Il Cinema in Piazza.” The group had put their 10-year anniversary video to the song “Città vuota”, and that summer, situated on folding chairs in Trastevere’s Piazza di San Cosimato, I was going through yet another heartbreak. What I was waiting for was relief, and I finally felt a sense of touched understanding when Mina, with her heavy yet impassioned voice, wailed: “Io penso sempre a te, soltanto a te, e so che la città vuota mi sembrerà se non torni tu.” (“I’m always thinking about you, only about you, and I know that the city will seem empty if you don’t come back.”) In the “Città vuota” universe, Mina is surrounded by suitors but has feelings for only one. I liked that there was a certain agency in that—not the dejected woman but the woman who chose.

In many ways, Mina played this very role, the role of the woman who chose, in her very own life. In fact, the outlines of her story—as well as her aesthetic—have made her a sort of feminist icon in Italy, for a certain type of crowd. Shaved eyebrows, androgyny on album covers, sheer tights topped by miniskirts (in 1970, she was the first to wear one on Italian national television)–her creative choices boldly diverged from the status quo. In 2010, journalist Maria Luisa Agnese called the singer “the first feminist, even if she didn’t know it,” in an article for Corriere della Sera.

“Many are convinced that Mina, with her life so breezily nonconformist, is worth celebrating as a kind of proto-feminist,” Agnese writes. “She has clearly and forever been a symbol for women, but almost in spite of herself, in an involuntary way: in the end, if anything, she has been a feminist model, but it all happened out of every code, without any plan, in a flow of personal expression that always led her to do things in her own way.”

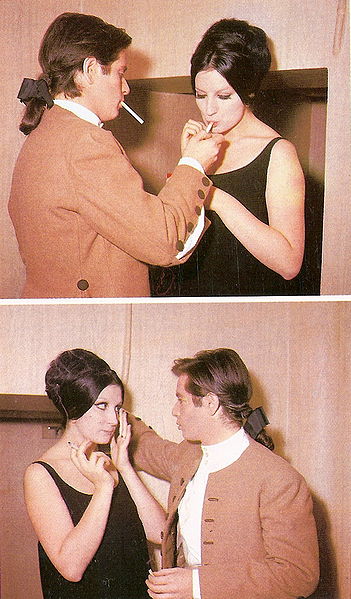

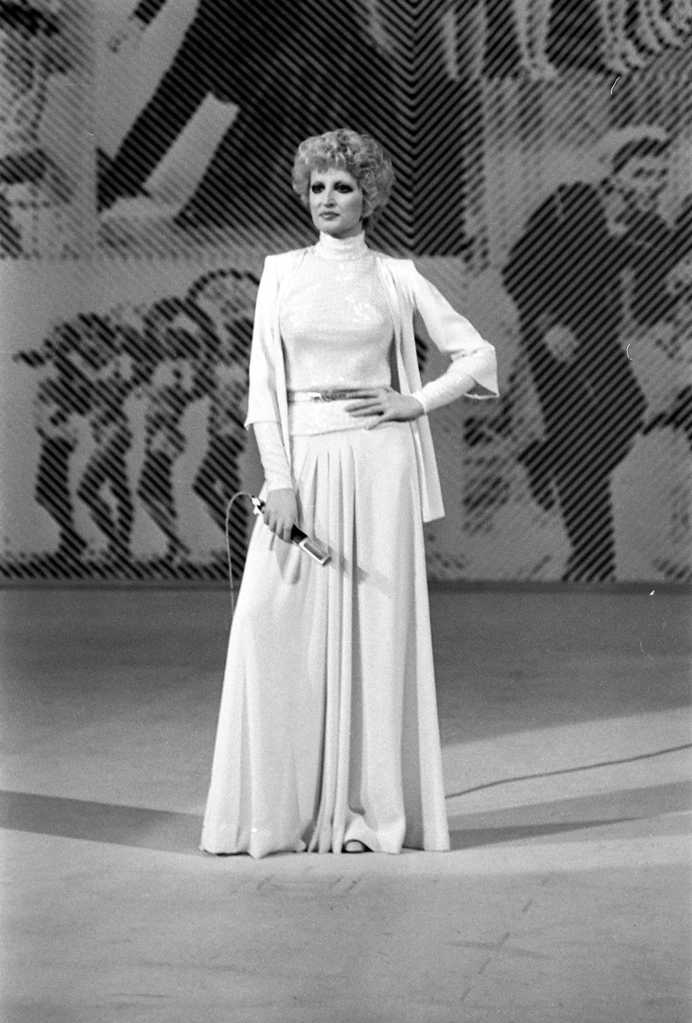

Mina backstage at RAI

Speaking to Italy Segreta, Mina’s son, Massimiliano Pani, notes that he agrees with this assessment.

“Mina lived firsthand the consequences of her personal life. She suffered a heavy judgement from a bigoted Italy of the 1960s, like when she was ostracized by RAI, which would no longer let her work,” he tells me. “She was attacked and hated by half of Italy and loved and admired for her courage by the other half. It was a large emotional burden for a 22-year-old girl. But Mina embodied what many Italian girls were experiencing. Her ‘sacrifice’ was the beginning of a modernization in the mentality of Italian society.”

Pani is right to say that Mina suffered, literally, “in first person” the very circumstances of her personal life in an Italy that did not accept much straying from the Catholic norm of family and marriage. In 1962, Mina went to a dinner with mutual friends and met Corrado Pani, still married but separated for at least a year (at the time, divorce was not yet legal), and not long after, Massimiliano was born. This was the final straw in a relationship that Italy would not condone—she was kicked off of RAI and, effectively, from Italian TV, for two years. But this censorship would not be permanent, in large part because Mina’s fan base simply would not allow it.

“RAI made an extreme move,” Pani explains. “But then they realized that they did not have another option of Mina’s stature for their Saturday night shows, and they had to call her back. The fearless girl had won her battle and, in some way, a share of Italian girls with her, changing the feeling and the customs of a society in conflict and unrest.”

Mina spoke not only with her actions but with her lyrics, which, much like “Città vuota,” manage to convey both strength and intimacy. They are also marked by a certain sensuality—so much so that Chiara Murru, a professor in Humanistic Studies at Siena’s University for Foreigners, presented on the female figure in Mina’s lyrics for the Accademia della Crusca, the top research institution of Italian language. She refers first to “L’importante è finire” (“The important thing is to finish”), a double entendre so clear that RAI decided to censor the song for its sexual content.

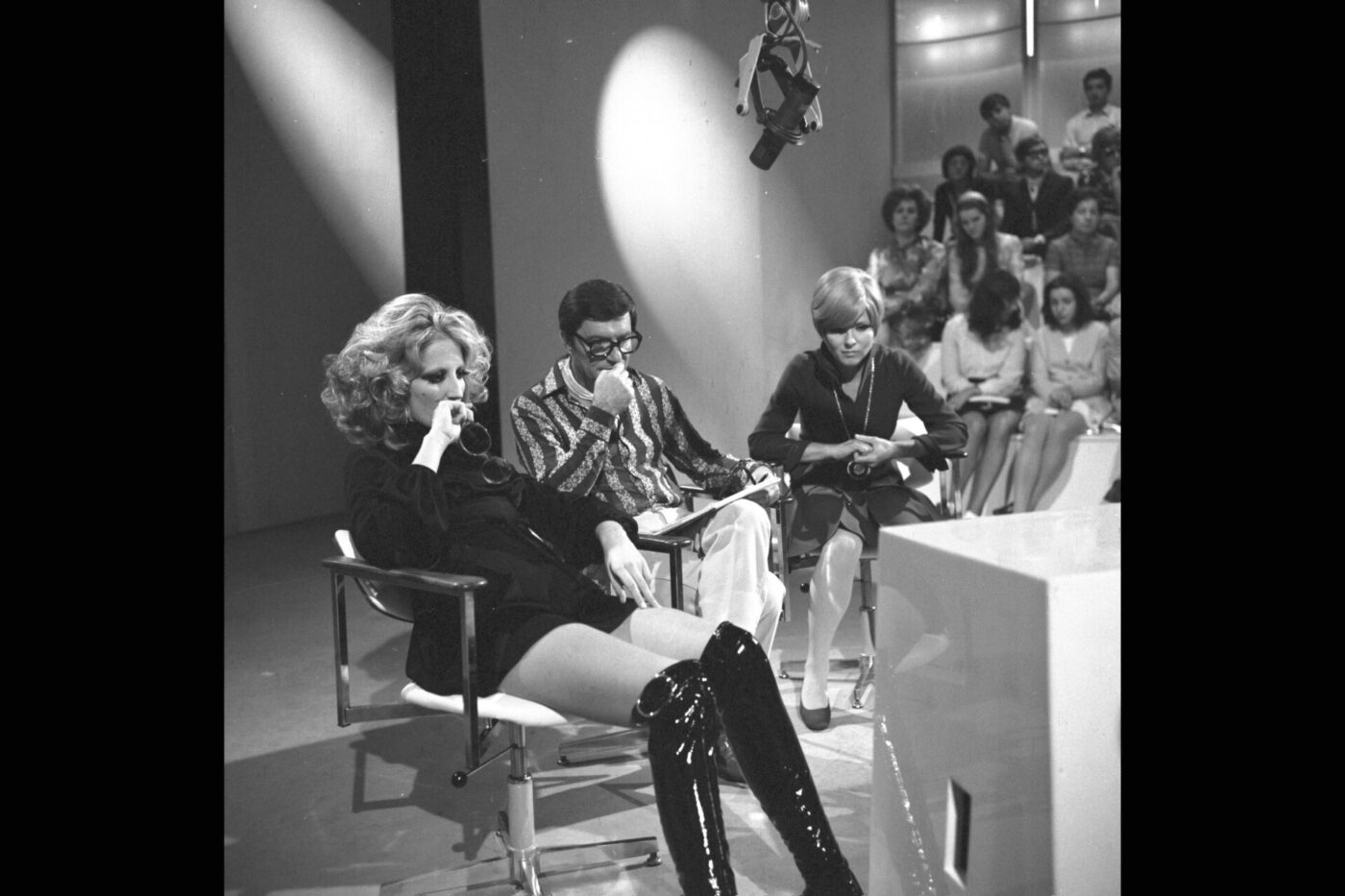

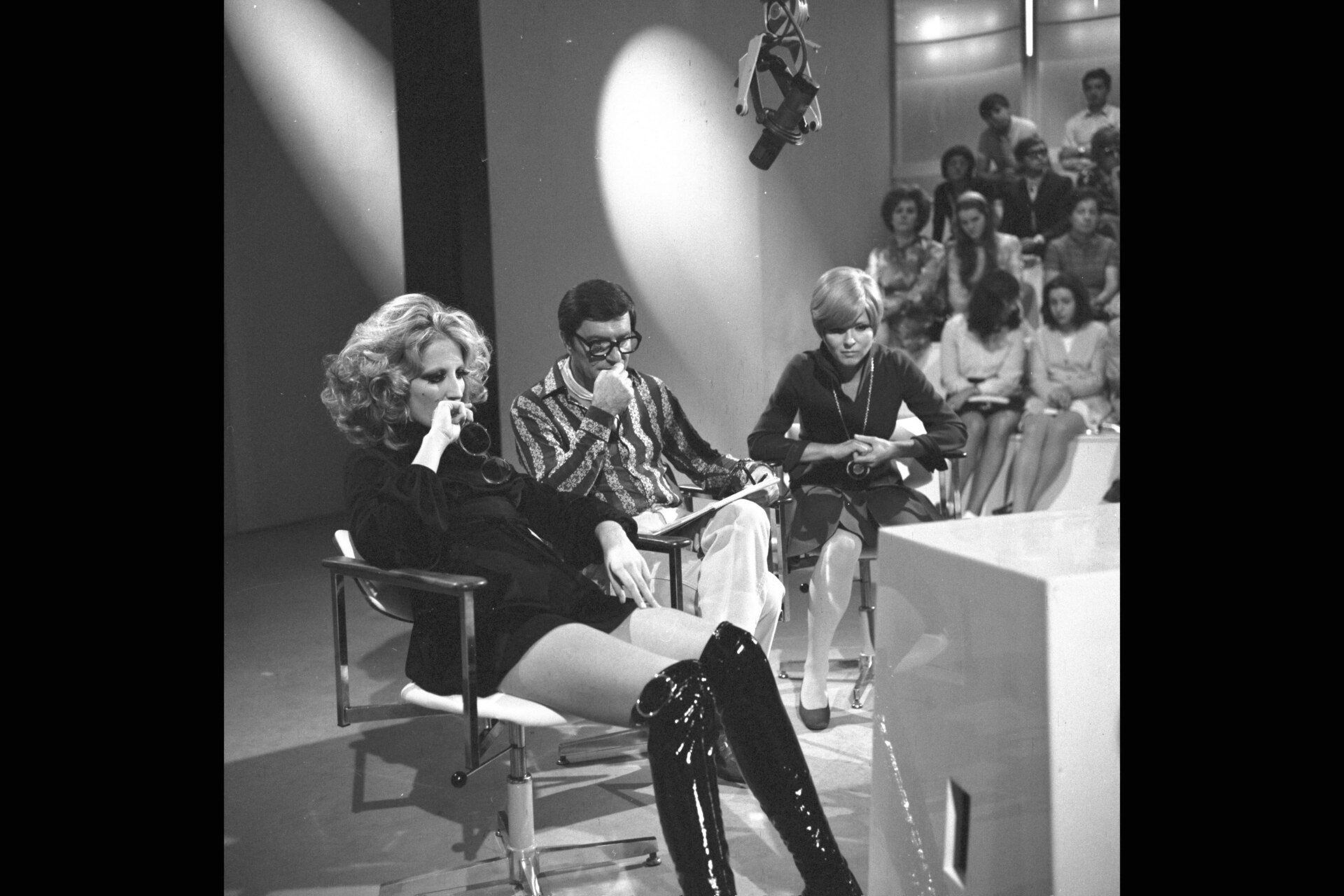

Mina hosting RAI's Milleluci (1974); photo courtesy of Archivio RAI

In another song, “Anche un uomo” (“Even a man”), Mina takes on the role of the wise, mature woman counseling the young girl for whom her partner will leave her. The song’s tone is “prescriptive, almost like an instruction manual (introduced, indeed, by the verb, spiegare, explain), that carries with it very strong semantic implications,” Murru writes.

“Ragazza mia, ti spiego gli uomini, ti servirà quando li adopererai: son tanto fragili, fragili, tu maneggiali con cura, fatti di briciole, briciole che l’orgoglio tiene su,” Mina sings. “Ragazza mia, sei bella e giovane, ma pagherai ogni cosa che otterrai: devi essere forte, ma forte, perché dipenderà da te, tu sei l’amore, il calore che avrà la vita che vivrai.” (“My dear, I’ll explain men to you, you’ll need it when you will use them: they are so fragile, fragile, you need to handle them with care…made of crumbs, crumbs that their pride holds up. My dear, you are beautiful and young, but you will pay for everything that you get: you have to be strong, strong, because it depends on you, you are the love and the warmth that the life you live will have.”)

What sets Mina’s writing apart is that very understanding, Murru notes, “the image of a complex and aware woman that moves, miraculously at ease, between the clichés that have always surrounded her and the proud decision to overturn them.” Mina, after all, experienced her peak of fame in the 1960s and ‘70s, in an Italy in which women were still denied many rights. Women had only gained the right to vote in 1945, while the right to divorce and the right to abortion didn’t come, respectively, until 1970 and 1978. Mina, a woman who sang frankly about love and sex in a way that showed her to be an active and conscious participant, clearly bucked against the norms.

But so much of this was unintentional, Pani says. In fact, Mina was not actively trying to communicate a feminist message in her songs. She was just trying to show the reality of human relationships.

“She talks about love; sometimes happy, sometimes dramatic, nostalgic, without a future or without an end,” Pani says. “It is with her courage, intelligence, talent, and originality that she has inspired Italian women—and beyond.”

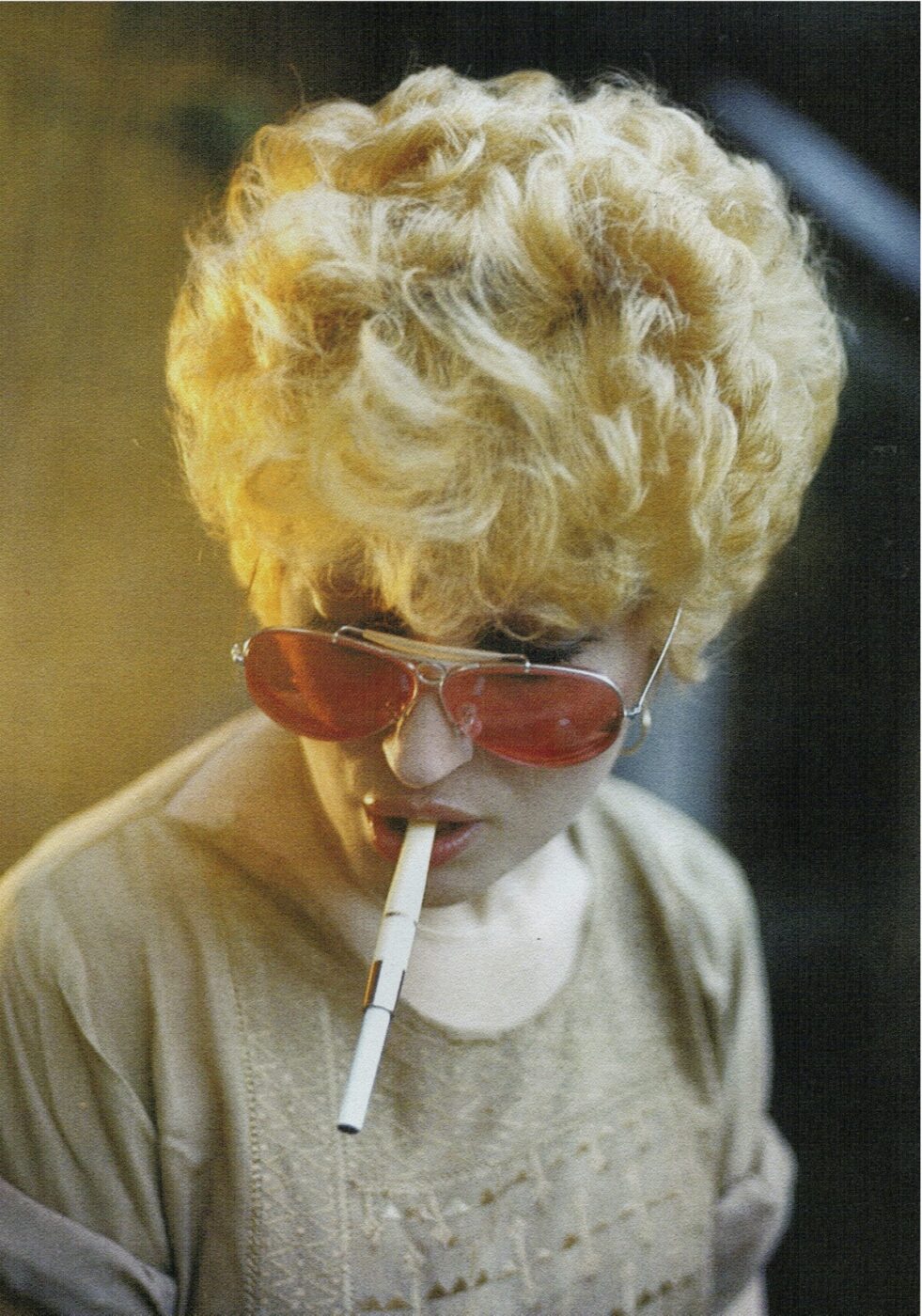

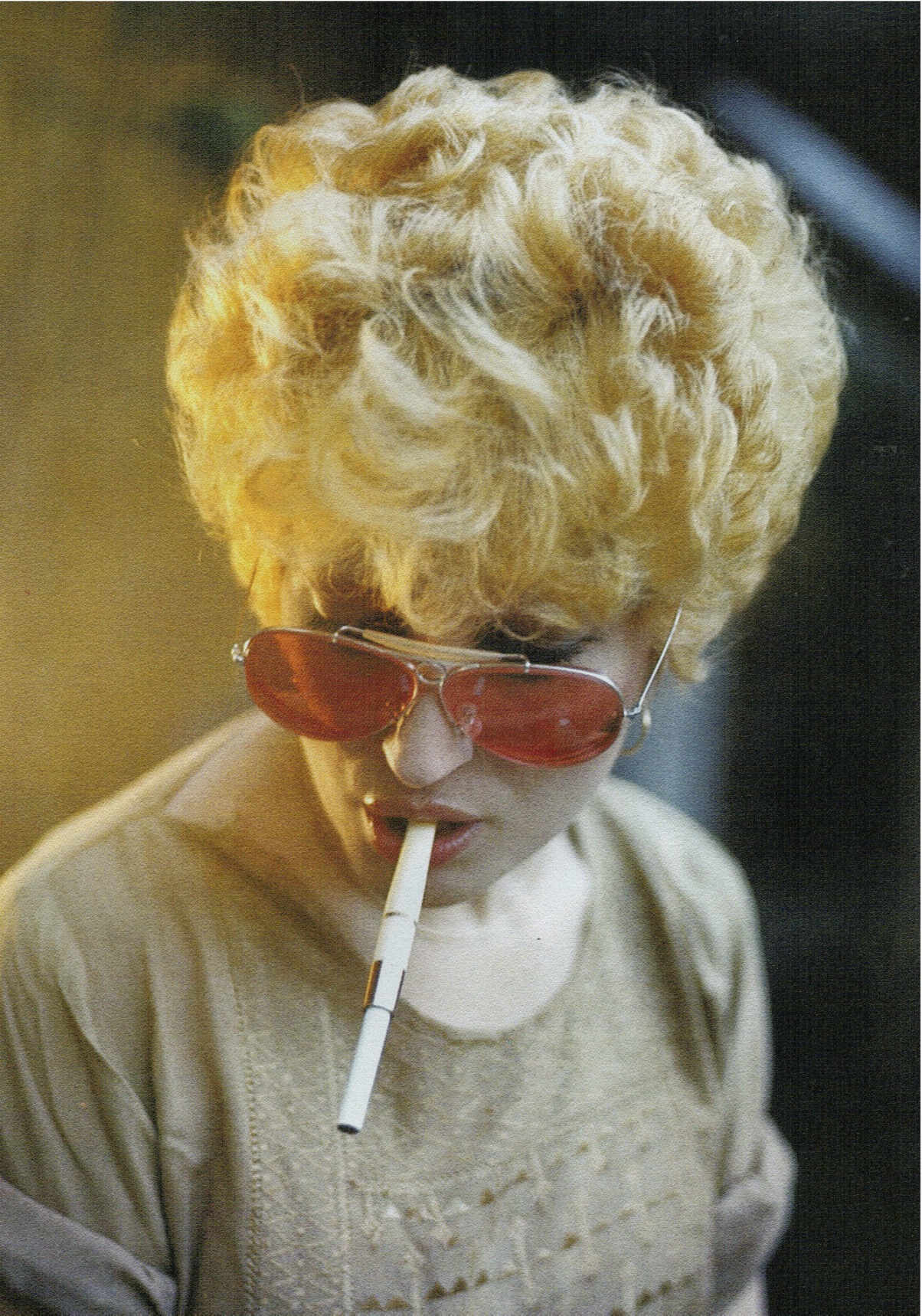

Photo by Mauro Balletti ©PDU

While it’s hard to imagine a woman getting kicked off of Italian television today for having a child with a married man, the undertones of sexism and the control of the Catholic Church still ring true to this era’s feminists.

“There are still very present and subtle ways of socially banning women—they receive so much criticism and are, at best, described as a courageous woman and, at worst, slut-shamed,” said Limertje Sieders, a Rome-based lawyer who co-hosts the transfeminist podcast Humvn with Daniela Maragno. “Men are not even remotely subjected to the same level of scrutiny.”

Sieders created Humvn in 2022 after receiving a Master’s degree in gender studies from Università Roma Tre. She was propelled by a desire to bridge her more academic and theoretical work with the reality of the gender dynamics she experienced in her daily life.

Maragno, on the other hand, had a more individual awakening to feminism, finally able to identify at a certain point that the subtle, internal discontent she had felt practically all of her life came from somewhere. Sieders likens it to the “matrix,” in which suddenly the underlying code that forms everything is made visible.

“I didn’t know that what I was feeling was part of a system, of the patriarchy,” Maragno said. “I just felt that I was unhappy and angry, and I didn’t know that that anger had a name.”

Both Sieders and Maragno were quickly able to put Italy’s own cultural and feminist context into a global one—the former was raised in Italy by Dutch parents and studied in The Netherlands and South Africa and the latter lived and worked in Ireland and the United States. When Maragno watched her home country from the outside, as an expat, she was disappointed by the way she saw Italy’s stories being told.

“When I was living abroad, I was getting all of this news from Italy that was really disheartening from a political standpoint—it seemed so backward,” Maragno said. “And then when I moved back to Rome, the feminist movement in Rome seemed so cool and there was so much going on, but it didn’t get a lot of visibility.”

Still, Maragno and Sieders don’t consider themselves acolytes at the altar of Mina, though they of course can easily name a few songs. But at feminist karaoke nights in Rome, the familiar strains of a Mina song will start playing, often “Se telefonando,” and Sieders will watch a group of friends get up and sing, united by a certain shared cultural history, even if the effect is almost involuntary at this point.

“Mina set an example of freedom. She showed that talent, intelligence, and hard work can give dignity to courageous choices,” Pani tells me. “Gen Z sees in Mina a courageous person who lived outside the box. They often define her as ‘ahead.’”

Photo by Mauro Balletti ©PDU