No, no, mai ti lascerò / no, no, sempre mio ti avrò.

No, no, I will never leave you / no, no, I will always have you mine.

The radio spouts Mina’s 1959 song “Mai” as Claudia (Monica Vitti), singing along, puts on her stockings. “Why am I so in love?” she asks her lover Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti), as he watches her.

Nel tormento più dolce sarò, coi miei baci ti riprenderò.

In the sweetest torment I will be, with my kisses I will take you back.

The music continues as Vitti presses him, “Tell me that when you go out without me, it’s like you didn’t have a leg.”

Sì, sì, sempre ti odierò / ma no, non ti perderò.

Yes, yes, I will always hate you / but no, I will not lose you.

It’s a moment of unexpected lightness in the otherwise enigmatic and somber narrative of Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960).

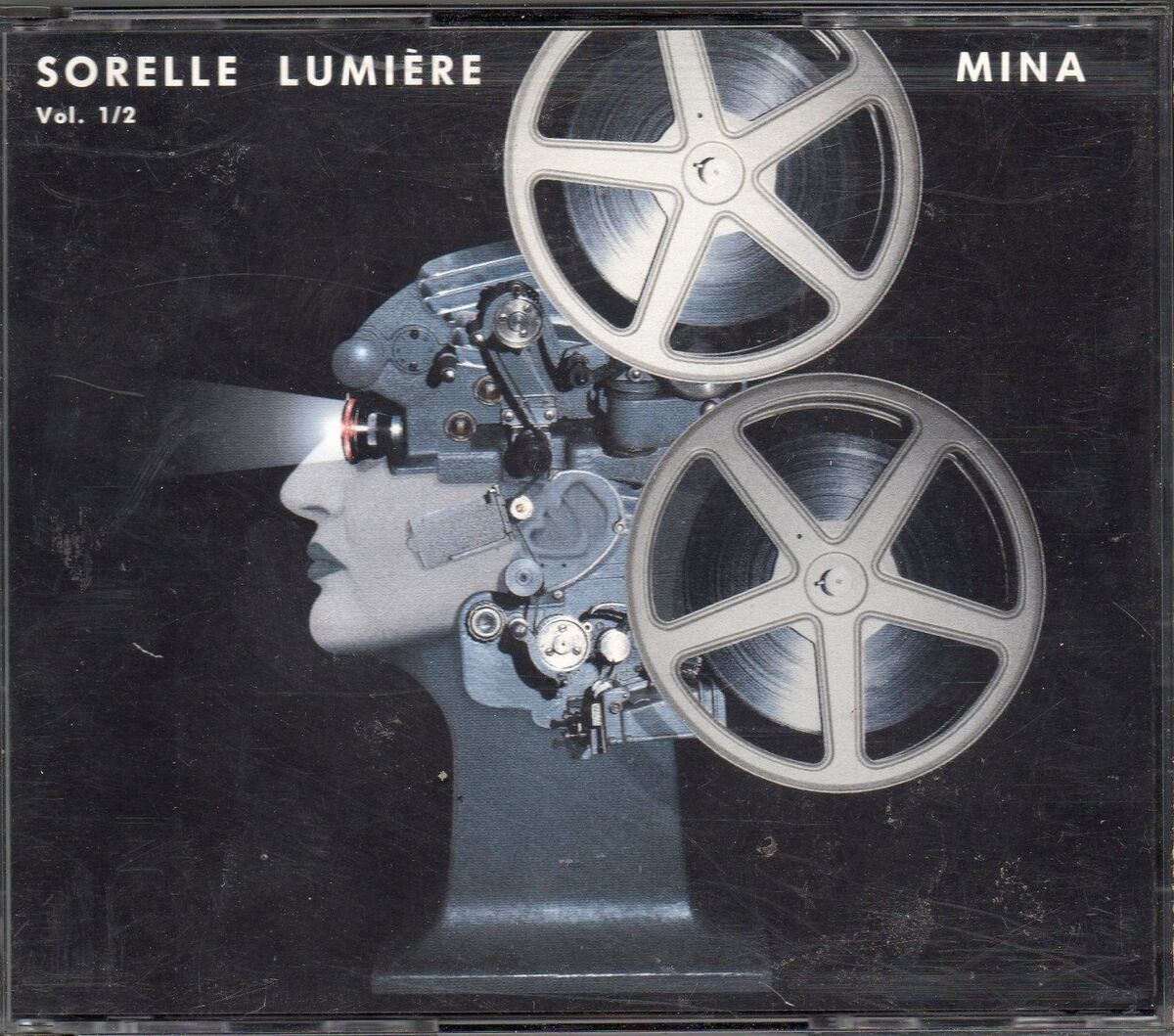

For over 60 years, film directors have been turning to Mina’s music to elevate their soundtracks, cementing her voice as a cinematic staple. One year after L’avventura, Antonioni opened L’Eclisse (1962) with another song by Mina, “Eclisse Twist”, an energetic piece abruptly interrupted by an ominous composition that foregrounds the tension between the film’s characters. In 1965, Luchino Visconti chose Mina’s melancholic “E se Domani” to accompany one of the first scenes of Vaghe stelle dell’Orsa, a tender dialogue between Claudia Cardinale and Michael Craig.

Alain Delon and Monica Vitti in L'Eclisse (1962)

More recently, she’s made vocal cameos in global hits like Spider-Man: Far from Home (2019) and season two of HBO series The White Lotus (2021), and Gabriele Muccino, Gabriele Salvatores, and Ferzan Özpetek have repeatedly used her songs in their films. The relationship between the latter and Mina has developed into a proper friendship, with the director sending her his scripts in preview. Özpetek’s film Nuovo Olimpo (2023) pays homage to the singer in the character of Titti, a lively cinema manager portrayed by Italian actress Luisa Ranieri, who is a devoted Mina fan and recreates her iconic makeup looks on herself. Mina herself suggested Ranieri for the role, and the resemblance is staggering.

In love with Mina’s voice, Martin Scorsese included “Il Cielo in una Stanza” in Goodfellas (1990), and used the same song in 2013 when directing a Dolce & Gabbana commercial with Matthew McConaughey and Scarlett Johansson. Another illustrious fan, Pedro Almodóvar, included the song “Come sinfonia” in his Dolor y gloria (2019), remembering when he would listen to Mina as a kid. In 2011, several websites reported that the Spanish auteur would direct a biopic about the Italian singer starring Marisa Paredes as Mina. The news was fake, but carried some wishful thinking.

While Mina’s voice has become a defining presence in cinema, she remains an elusive figure. Unlike many of her contemporaries who seamlessly transitioned between singing and acting–from Barbra Streisand and Cher to Lady Gaga and Harry Styles–Mina chose to avoid the spotlight of the silver screen and to step away from public life all together in 1978.

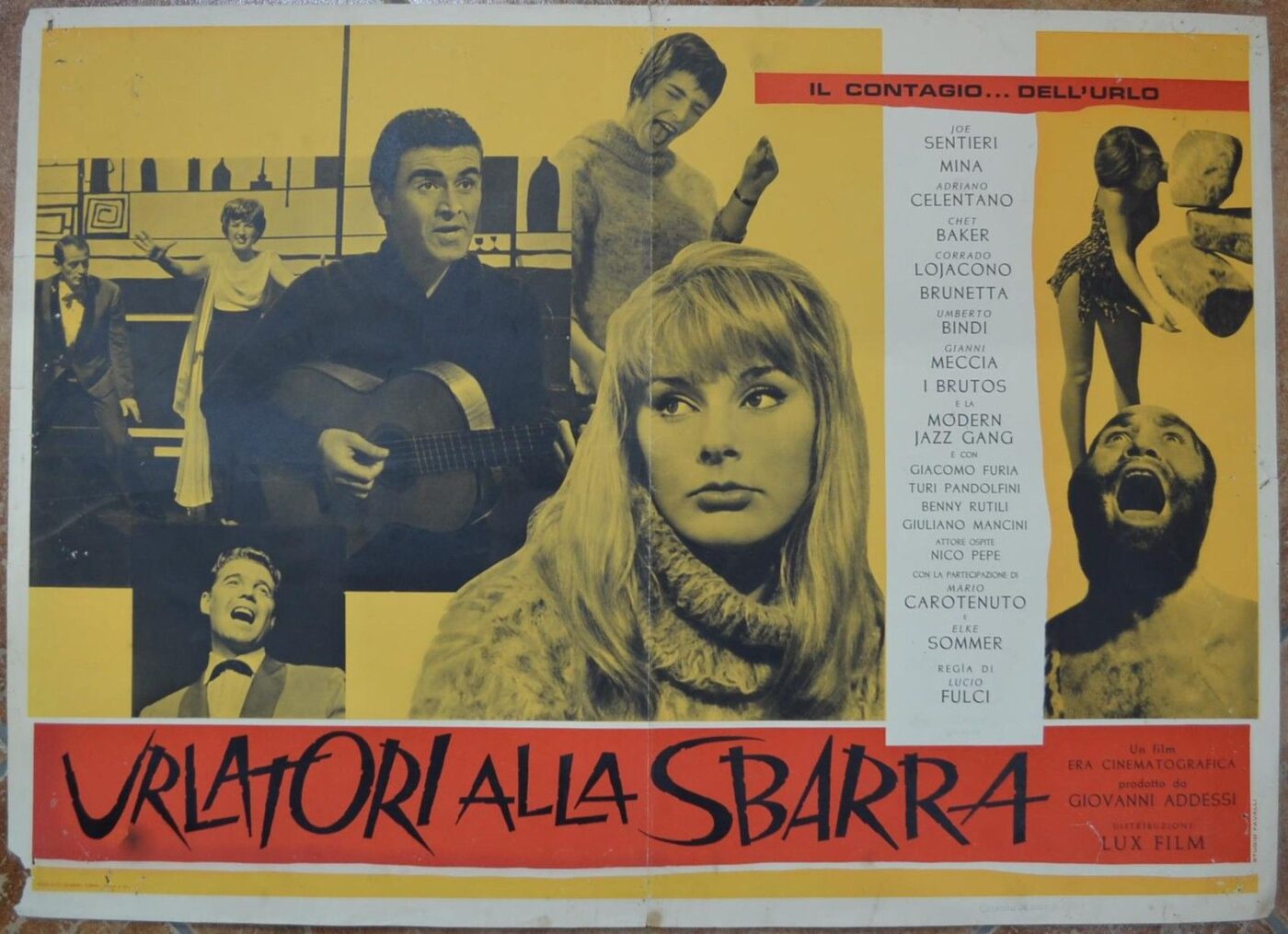

She repeatedly refused the many roles directors offered her over the years, with the exception of thirteen musical films she starred in early in her career, between 1959 and 1967. Aimed at captivating a young audience, these musicarelli–as they were known in Italian–were finely tuned commercial vehicles designed to catapult singers to stardom and showcase their latest hits. Mina, already a household name, often played herself in these films. While many musicarelli leaned on simple, formulaic love stories between starry-eyed youths, a few dared to push boundaries. Among these, Lucio Fulci’s Urlatori alla sbarra (1960) stands out as a vibrant homage to the cultural revolution that made music the heartbeat of the 1960s youth. The film, controversially banned for viewers under 18 due to its political undertones, immortalizes an iconic moment: Mina, snapping her fingers with unrestrained energy, singing “Nessuno” alongside a magnetic Adriano Celentano. (They would go on to collaborate on best-selling studio album Mina Celentano in 1998.)

Poster for Urlatori della Sbarra (1960), featuring Mina and Celentano singing "Nessuno"

Like anything else in her life, even Mina’s missed connection with the eighth muse is first-rate. Mike Nichols and Andy Warhol would have gladly directed her for her highly “cinematic” face. Alfred Hitchcock would have liked her to sing in one of his films.

Federico Fellini contacted her for a role in Il viaggio di G. Mastorna, detto Fernet, never realized, and wanted her in Satyricon (1969) as Tryphaena, later entrusted to the French actress Capucine. Francis Ford Coppola asked her to play Marlon Brando’s wife in The Godfather (1972), before going to Morgana King. In 1976, Vincente Minnelli tried to cast her alongside his daughter Liza in the film Nina.

Antonello Falqui, the TV director who had worked with Mina on popular TV shows such as Canzonissima, Studio Uno, and Milleluci, remembered how the singer once rejected his offer to star in a TV production of La vedova allegra, which he directed in 1968. “I’m a singer, I’m not an actress,” Mina answered firmly.

“Mina is a perfectionist. She has a very pragmatic approach,” Massimiliano Pani, Mina’s son and producer, tells me. “She knows that if she has to do something, she has to do it well. And out of a sort of modesty, she never wanted to be an actress. Not because she wouldn’t have succeeded–she would have succeeded very well. It was a choice dictated by rigor. She always tries to give the best she can to her public.”

And so, Mina’s voice remains her truest legacy: unbound by the screen yet omnipresent in its stories, lending a voice to the unsaid and a heartbeat to the unspoken. By refusing to compromise her art for cinematic glitz, Mina proves that the most powerful presence is the one that lets its talent speak for itself.