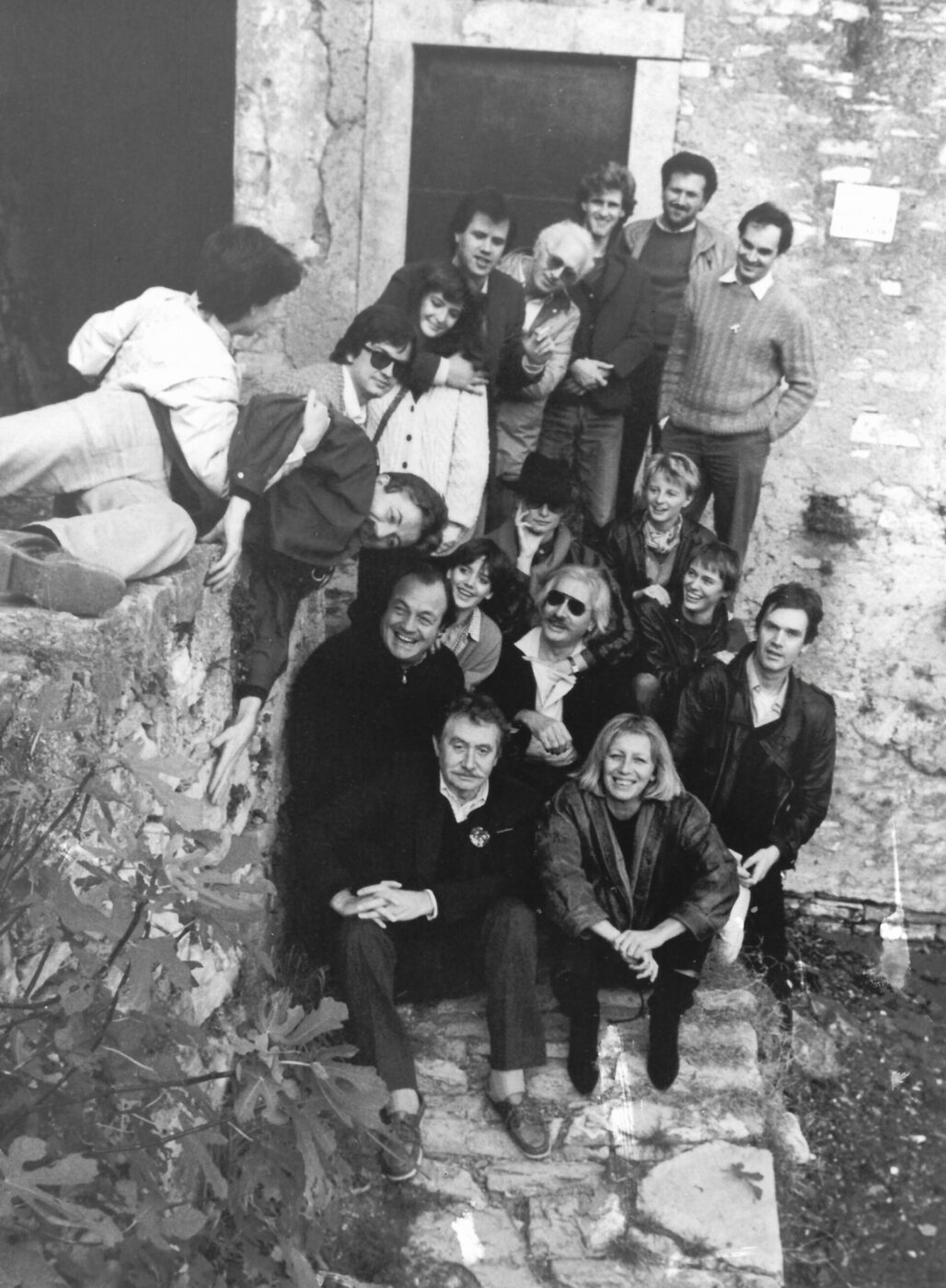

A group photo in Masanori Umeda’s Tawaraya boxing ring; Photo courtesy of Memphis

December 11th, 1980. A group of radical designers and architects—both Italian and international—gathered in an apartment on Via San Galdino in Milan. Among them were Matteo Thun, Aldo Cibic, Martine Bedin, Marco Zanini, and Michele De Lucchi—all in their twenties. Hosting them was Ettore Sottsass, the 63-year-old titan of Italian design and architecture.

What united this unlikely crew was a shared boredom with the rules of modernist design—practicality over emotion—and on the table was Sottsass’s plan to create a new line of furniture for his longtime carpenter friend, Renzo Brugola. But something shifted. As Bob Dylan’s “Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again” played on repeat, the group decided to break with canon—and start their own movement. They would go on to redefine the aesthetics of the 1980s with loud colors, cartoonish forms, and geometric irreverence—spreading their postmodern gospel across furniture, fashion, and pop culture.

They called themselves Memphis, a nod to the song on repeat, but also for the layered references it carries: Memphis, Tennessee and ancient Memphis in Egypt; rock ’n’ roll and Ptah, the Egyptian god of craftsmen; low-brow and high-brow culture; an international sensibility tempered by a good dose of playfulness.

Sottsass, the eldest by decades, was considered the group’s leader—a title he resisted, as it contradicted the collaborative spirit at the heart of Memphis’s philosophy. Born in 1917 to an Italian father and an Austrian mother, he fought in WWII before throwing himself into the design scene of post-war Milan. In 1949, he married the famous writer and translator Fernanda Pivano, who catapulted him into the international literary scene; he became friends with the likes of Ernest Hemingway and Allen Ginsberg, with whom he briefly created the art magazine Pianeta Fresco. He took photographic portraits of Hemingway and Ginsberg, as well as his Beat colleague Jack Kerouac, the aforementioned Bob Dylan, Picasso, Max Ernst, Alberto Moravia, and Robert Mapplethorpe.

Despite the numerous accolades under his belt, he is perhaps best known for the designs he created for Olivetti, including the portable cherry red Valentine typewriter, which turned into a suitcase, and the mainframe computer Elea 9003, which was as sexy as a computer could be in 1959, decades before Apple made that into a mission statement.

Practicality bored him. When designing everyday objects, rather, he cared how it made someone feel—a break from the reigning design ideology that “form follows function.”

Ettore Sottsass and his Carlton room divider; Photo courtesy of Memphis

These ideas were music to the ears of the young designers gathered at his apartment that winter evening. Modernist minimalism had stopped being interesting, along with the drab earth tones of the 1970s. They wanted to make designing a chair fun again. George Sowden, Nathalie du Pasquier, Peter Shire, Michael Graves, and others joined, and by February, the group had produced over a hundred designs for furniture, ceramics, and lamps.

“No one talked about forms, colors, styles, or decorations,” noted design critic, and Sottsass’s second wife, Barbara Radice. Though there was no predefined approach, hallmarks included the exploration of unconventional materials, kitsch motifs, and bold color experiments first initiated by Studio Alchymia, the radical Italian design group to which Sottsass and De Lucchi had belonged in the 1970s. After years of modernist constraints, Sottsass and the rest yearned to break free from the impersonal “good taste” that had dominated the design world.

A few months later, a drawing by Lucian Paccagnella—of a yawning dinosaur against a lightning-filled sky—invited critics and viewers to Arc ’74 during the September 1981 Salone del Mobile for the unveiling of Memphis’ first collection. Sottsass was running late. As he arrived, traffic was blocked and the crowd so rowdy that he mistook the opening night commotion for a terrorist attack (these were the Years of Lead after all).

On display was Peter Shire’s Bel Air Chair, a homage to west-coast American surf culture with a shark fin-shaped back, asymmetrical geometric shapes, and mismatched colors. Michael Graves’s Art Deco-inspired Plaza vanity mirror sparkled in green lacquered wood, and Sottsass’s own Carlton room divider—an anthropomorphic thing that doubled as a bookshelf—struck a pose with brightly colored arms outstretched. Each design was named after a luxury hotel—a tongue-in-cheek nod to the irony of their cheap construction. Laminates, painted wood, and plastics mimicked expensive finishes, creating a faux-chic aesthetic that mocked the very idea of taste.

Plaza vanity mirror by Michael Graves; Photo courtesy of Memphis

Bold, unconventional, hilarious, and most of all impractical, the pieces set the design world on fire. Love them or hate them, for the next few months, it was all design magazines could talk about. “A bolt out of the blue, red and yellow,” Lester Dundes, publisher of Interior Design magazine, described the debut. “A shotgun wedding between Bauhaus and Fisher-Price,” another famously wrote, though I would add into the mix De Stijl, Kandinsky, Italian Futurism, and African tribal patterns. For some, Memphis Design was an affront to good taste; for others, an exciting new vision. Memphis was fake, but authentic. It was elegant, but in bad taste. It was high brow, yet low-brow. There was only one thing all could agree on: it was disruptive.

The group's best-selling piece of furniture—the First Chair by Michele De Lucchi—reportedly prone to falling over backwards; Photo courtesy of Memphis

Though Memphis was primarily a furniture and interior design collective, their work was never mass-produced—a fact made even more strange by the use of low-cost materials. The best-selling piece of furniture from Memphis is the First Chair by Michele De Lucchi. Essentially a stool, with a single circular disk for a backrest, it’s Memphis to the extreme—cool and geometric, while simultaneously looking like the most uncomfortable chair you’ve ever seen, reportedly prone to falling over backwards. It only sold about 3,000 units. Perhaps because the works were perceived as conceptual, belonging more to a museum than a home. Only true eccentrics would decorate their spaces in Memphis style. One such sponsor was famed fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld, whose Monte Carlo home was fully decked out in Memphis. He had George Sowden’s Oberoj armchair, the Carlton room divider, Masanori Umeda’s Tawaraya boxing ring in wood (in which the Memphis group famously took a group portrait), and the Plaza vanity, among others. Another great collector was David Bowie, whose Memphis furniture collection was auctioned at Sotheby’s after his passing in 2016.

Karl Lagerfeld in his Monte Carlo home; Photo ©Jacques Schumacher

Ettore Sottsass left Memphis in 1985 to pursue his own projects, and when the 1987 Black Monday crash sent shockwaves through the art market—a moment often cited as the death knell of postmodernism—the rest of the group followed suit.

Memphis may have flopped as functional furniture, but function was never the mission. Inspiration was. And in that, it succeeded—spectacularly.

Outside the confines of the design community, Memphis had broad appeal. The media fawned over the group, their opening parties were always widely attended, the designers were young radicals, and the aesthetic was perfectly in line with the post-punk, new wave aesthetics of the early 1980s. MTV had launched just one month before the first Memphis showcase, and its glossy logo, which flashed different neon colors and graphic patterns, was perfectly in tune with the Memphis look. As was graffiti art by a young, up-and-coming artist in New York by the name of Keith Haring. Around the same time, Hartmut Hesslinger opened his Frog Design studio; while designing human-focused products for Apple, he coined the phrase “form follows emotion”—very much in line with the Memphis way of thinking.

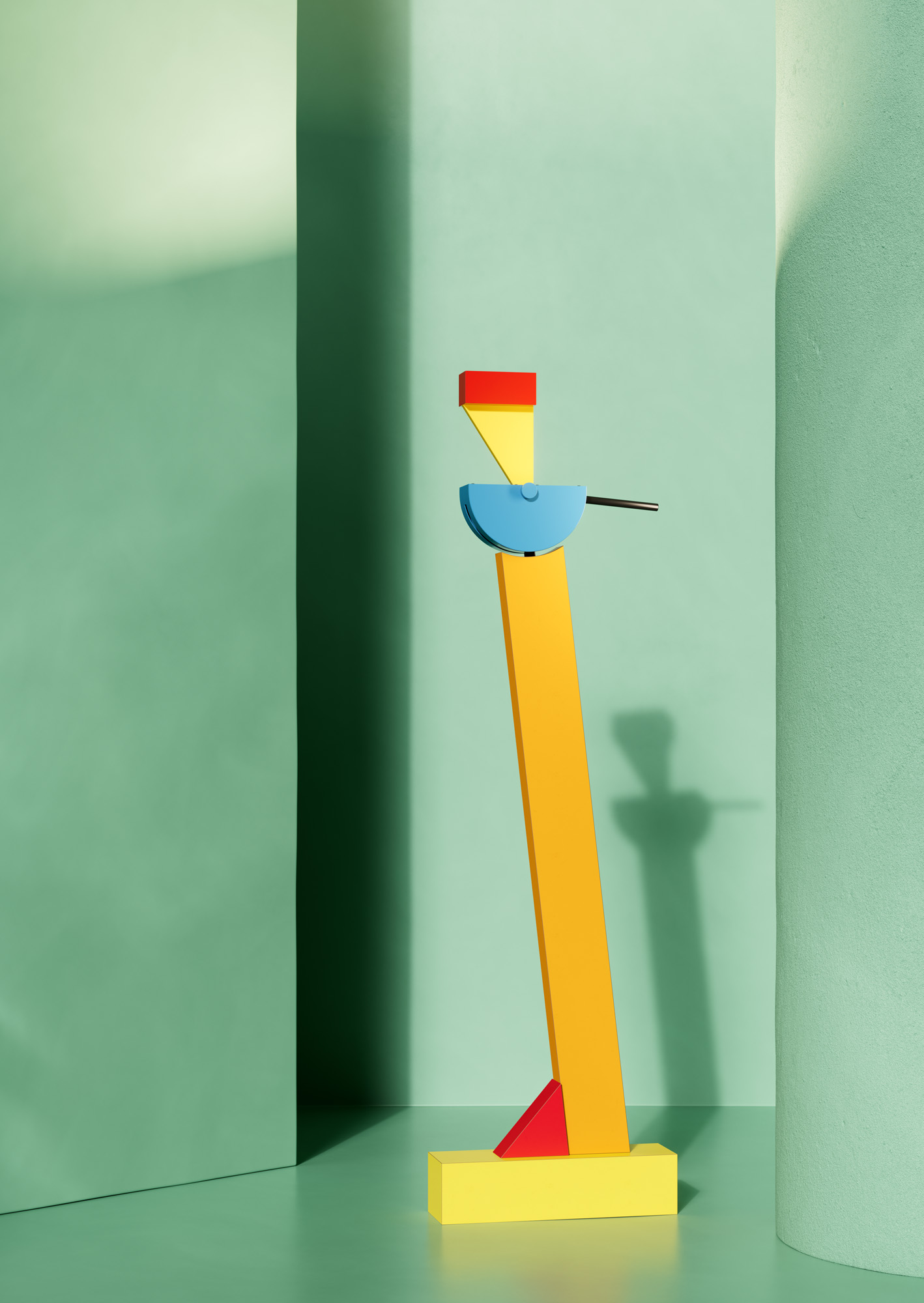

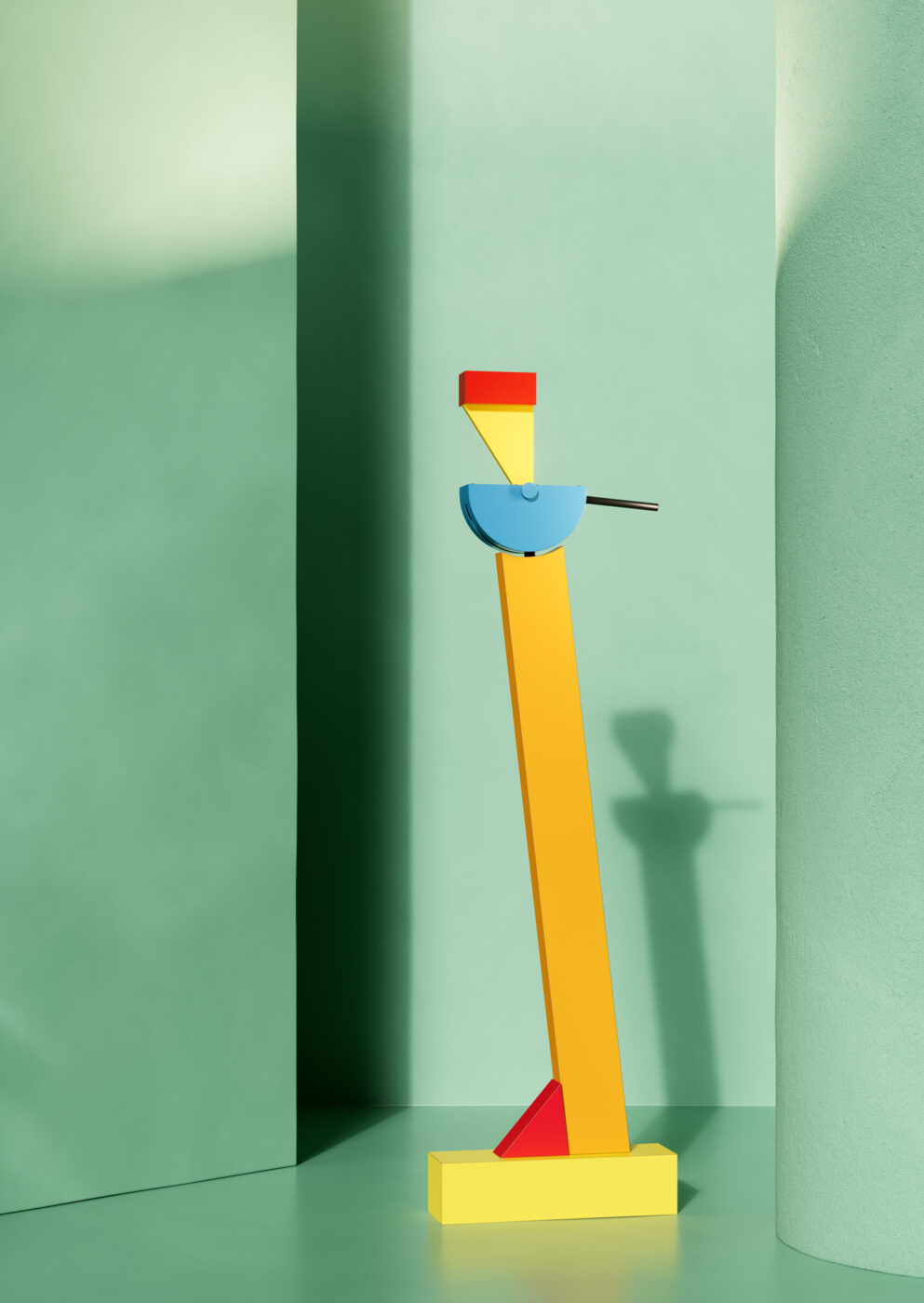

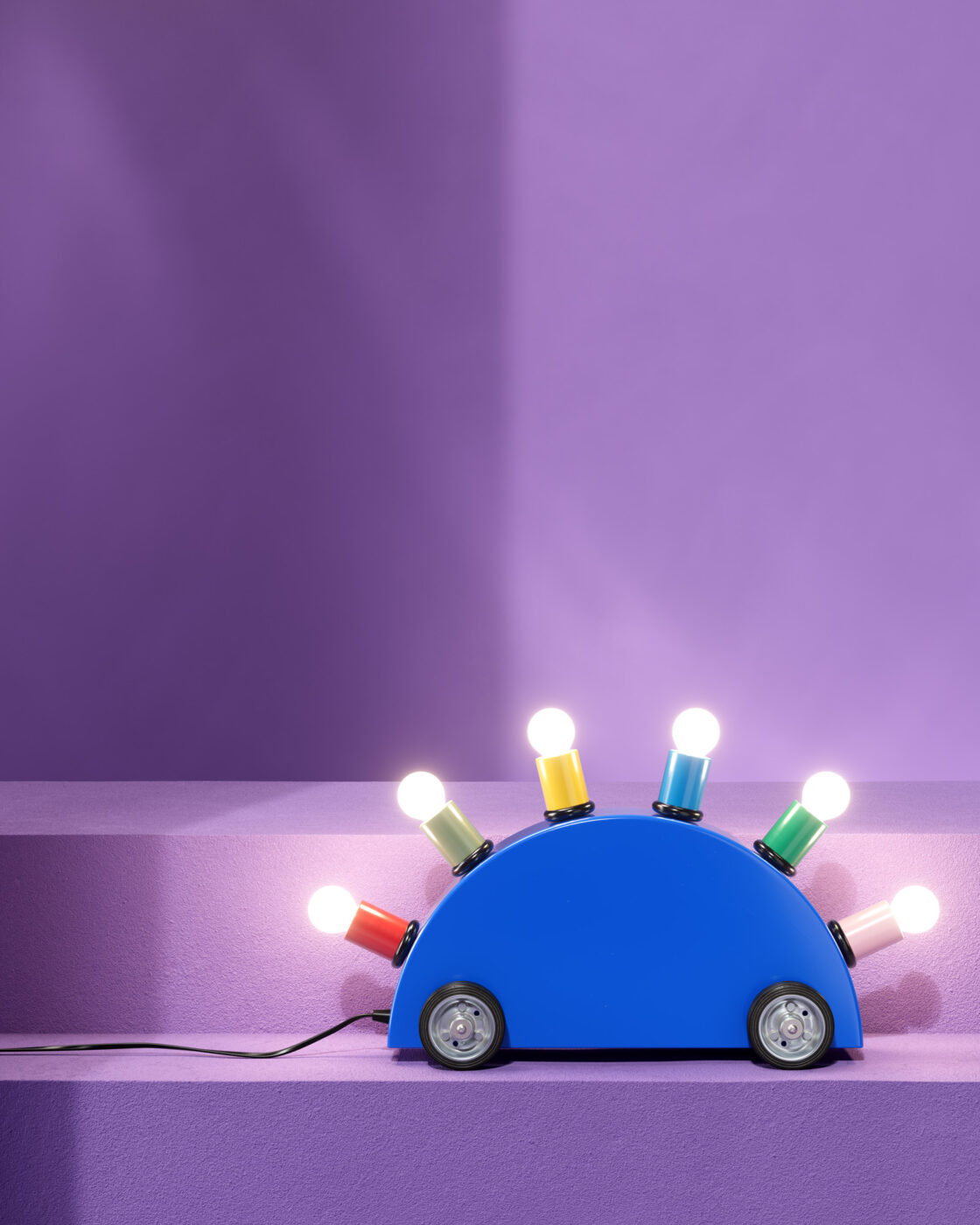

Ashoka lamp by Sottsass (named for the former emperor of the Maurya empire); Photo courtesy of Memphis

Neon colors, wacky geometric shapes, and graphic patterns went on to define the aesthetics of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. A cursory Google search of “‘80s pattern” is enough to confirm Memphis’ mark. The look of Saved by the Bell and Miami Vice on popular television, along with the aforementioned MTV, defined the decade, as did glam metal, hip-hop, graffiti, parachute pants, patterned fleeces, Swatch watches, polka dots, Missoni, and the Jazz cup design (introduced in 1992 but clearly Memphis inspired, this memeified design gained a cult following). During the decade, everything was unapologetically over the top.

Trends fade as people tire of them—until nostalgia revives what once felt dated. Memphis didn’t stay boxed in the ’80s. Its influence kept resurfacing, reinterpreted across decades. Like in 1995, when Apple bundled what it called an “Apple Watch” with their System 7.5 operating system: a blue steel circle with a thick green triangle for the hour, a red sliver for the minute, and a wiggly gold squiggle to track the seconds. Fashion houses periodically bring Memphis back, as Dior did in 2011 with a pair of high-heels inspired by Sottsass’s Tahiti lamp and Valentino in 2017; the collaboration with former Memphis designers Nathalie du Pasquier and George Sowden led to a collection that blended Memphis style with Victorian aesthetics. Or have a look at Vaporwave graphics, an internet culture from the 2010s composed of chopped and screwed music and a glitchy take on ‘80s and ‘90s visuals.

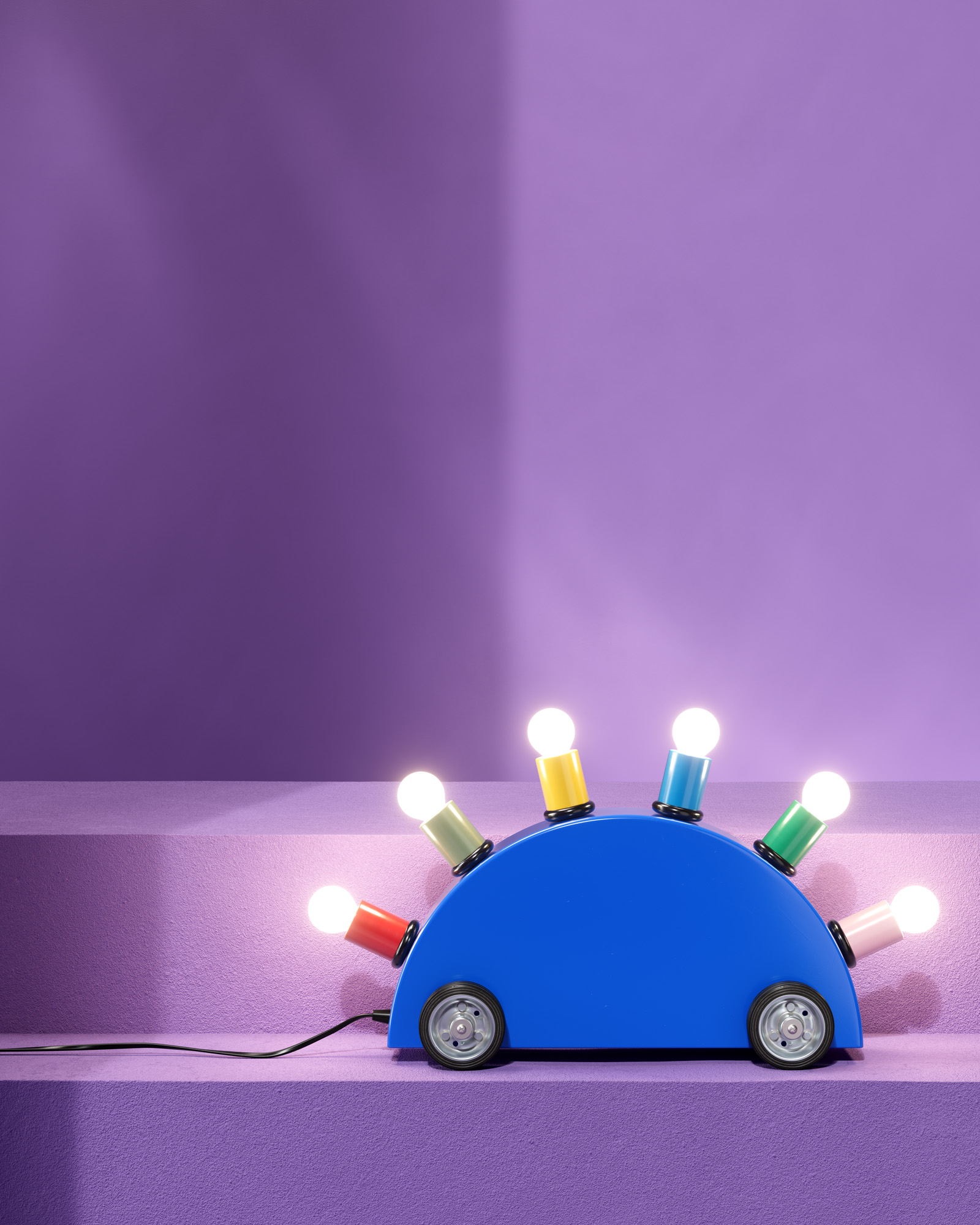

The Tahiti lamp by Sottsass inspired Dior's 2011 heels; Photo courtesy of Memphis

Design ideas spread like wildfire. Rarely do we ask where they come from—or who lit the match. They drift from their original purpose, morphing, mutating, and seeping into other fields. Nothing exists in a vacuum, and maybe it’s unfair to give Memphis all the credit. They were part of a moment, shaped by what was happening around them, and feeding off the same cultural currents as everyone else.

But they do deserve recognition—for proving that furniture and objects could be provocative, humorous, and deeply expressive. They shattered the self-seriousness of design and introduced a new kind of thinking: one where aesthetics, emotion, and experimentation mattered more than utility.

It’s never easy to pin a decade’s “look” to a single movement. But just this once, let’s indulge—and be proud that it all started in a little apartment in Milan.

The Memphis Group; Photo courtesy of Memphis